Introduction

The blood-brain barrier (BBB), first described by Paul Ehlrich (1885), is a highly selective semi-permeable membrane between the blood and brain interstitium. This unique barrier allows cerebral blood vessels to regulate the movement of molecules and ions between the blood and the brain.[1]

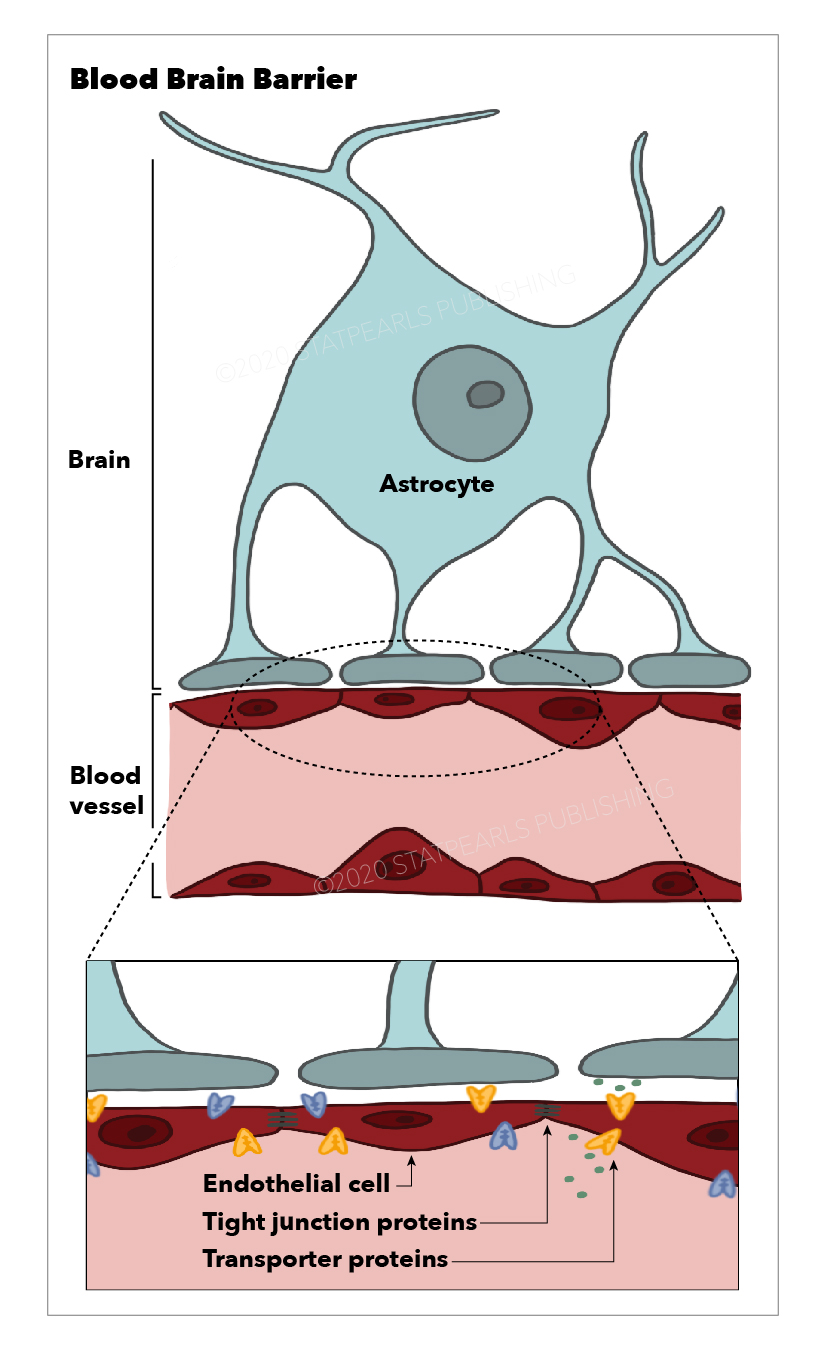

The BBB is composed of cerebral capillary wall endothelial cells (ECs) held together via tight junctions (TJs). These TJs, surrounded by pericytes, astrocytes, and the basal lamina, contribute to the highly selective nature of the BBB, limiting the passage of substances from the blood to the brain more so than any other capillaries in the body.[2] See Figure. Blood Brain Barrier.

Issues of Concern

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Issues of Concern

The BBB tightly controls the entrance of molecules from the plasma into the central nervous system (CNS) and plays a critical role in proper CNS function. BBB dysfunction can be seen in numerous chronic degenerative neurologic disorders such as Alzheimer disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), multiple sclerosis (MS), and Parkinson disease, as well as acute CNS disorders such as traumatic brain injury (TBI) and stroke.[3]

Cellular Level

All blood vessels are made up of two distinct cell types, ECs and mural cells, with the latter composed of vascular smooth muscle cells and pericytes. While ECs are the main component of the BBB, allowing for high selectivity, the interactions between ECs and mural cells allow for induction and maintenance of the BBB. Other vital interactions include ECs and immune cells, neural cells, and glial cells.[1]

Endothelial Cells

ECs are modified simple squamous epithelial cells derived from mesoderm, which form the walls of blood vessels. ECs of the CNS have unique properties allowing for tight regulation of the movement of molecules, cells, and ions between the blood and the brain. In addition, the tight junctions which hold CNS ECs together are responsible for the limitation in the paracellular flow of solutes.

Mural Cells

Mural cells include vascular smooth muscle cells and pericytes (PCs), which incompletely cover the endothelial walls of the microvasculature. PCs extend long cellular processes along the abluminal surface of the endothelium that contain contractile proteins, allowing them to contract and control the capillary diameter.[4]

While PCs in peripheral tissues are derived from the mesoderm, CNS PCs form from the neural crest. This critical difference gives CNS PCs unique properties, making them essential in the regulation and formation of the BBB during development. They also maintain the function of the BBB in adulthood and throughout the aging process.[5]

Development

The development of the BBB is a multistep process beginning with angiogenesis. Pre-existing vessels sprout into the embryonic neuroectoderm, giving rise to new vessels which exhibit many BBB properties, including the expression of TJs. Barrier properties of the BBB mature as growing vessels come into contact with pericytes and astroglia. This process includes the elaboration of TJs, decreased transcytosis, downregulation of leukocyte adhesion molecules, and increased efflux transporter expression. Sealing of inter-endothelial TJs is completed during maturation and must be maintained throughout life.[6]

Many known cellular and molecular mechanisms mediate brain angiogenesis, with ongoing research focusing on more CNS-specific pathways (Wnt/Beta-catenin) and molecules (GPR124) as crucial in the differentiation and maturation of the BBB.[7]

Organ Systems Involved

The BBB is the central element of the neurovascular unit (NVU), consisting of tight junctions between endothelial cells. These NVUs exist within the capillaries and post-capillary venules that vascularize the CNS, including most parts of the brain and the spinal cord. A notable exception is a group of specialized neuroepithelial structures within the CNS, termed the circumventricular organs (CVOs). Unlike the remainder of the CNS, CVOs are vascularized by fenestrated capillaries, allowing bidirectional communication between blood and the brain. Grouped at the midline of the brain proximal to the third and fourth ventricles, CVOs perform regulated secretory and sensory functions that, due to the BBB, the remainder of the CNS cannot.[8]

Seven significant CVOs are grouped by function into secretory and sensory organs. The four secretory CVOs are the median eminence, neurohypophysis, pineal gland, and sub-commissural organ. The three sensory CVOs are the area postrema, the subfornical organ, and the organum vasculosum of the lamina terminalis. These structures and their fenestrated capillaries play critical roles in neuroendocrine function.[9]

Recent MRI studies have also indicated that while the BBB regulates blood-brain interaction, the brain utilizes lymphatic vessels in the dura mater to directly communicate with the peripheral immune system, which plays a role in CNS immune response and toxin transport.[10]

Function

The essential function of the BBB is the maintenance of brain homeostasis. This is achieved via tightly regulated ion and solute transport between the intravascular plasma and the CNS through molecular exchange pathways that transport molecules from the blood to the brain and vice-versa. However, not all molecules require transport mechanisms across the BBB. Gases such as carbon dioxide and oxygen, and lipophilic molecules with a molecular weight under 400 Da can freely diffuse across the BBB. While astrocytes play a significant role in stabilizing and maintaining BBB integrity, the capillary ECs and pericytes contain the most critical BBB transport mechanisms and pathways.[11]

Mechanism

Transport Across the Blood-Brain Barrier

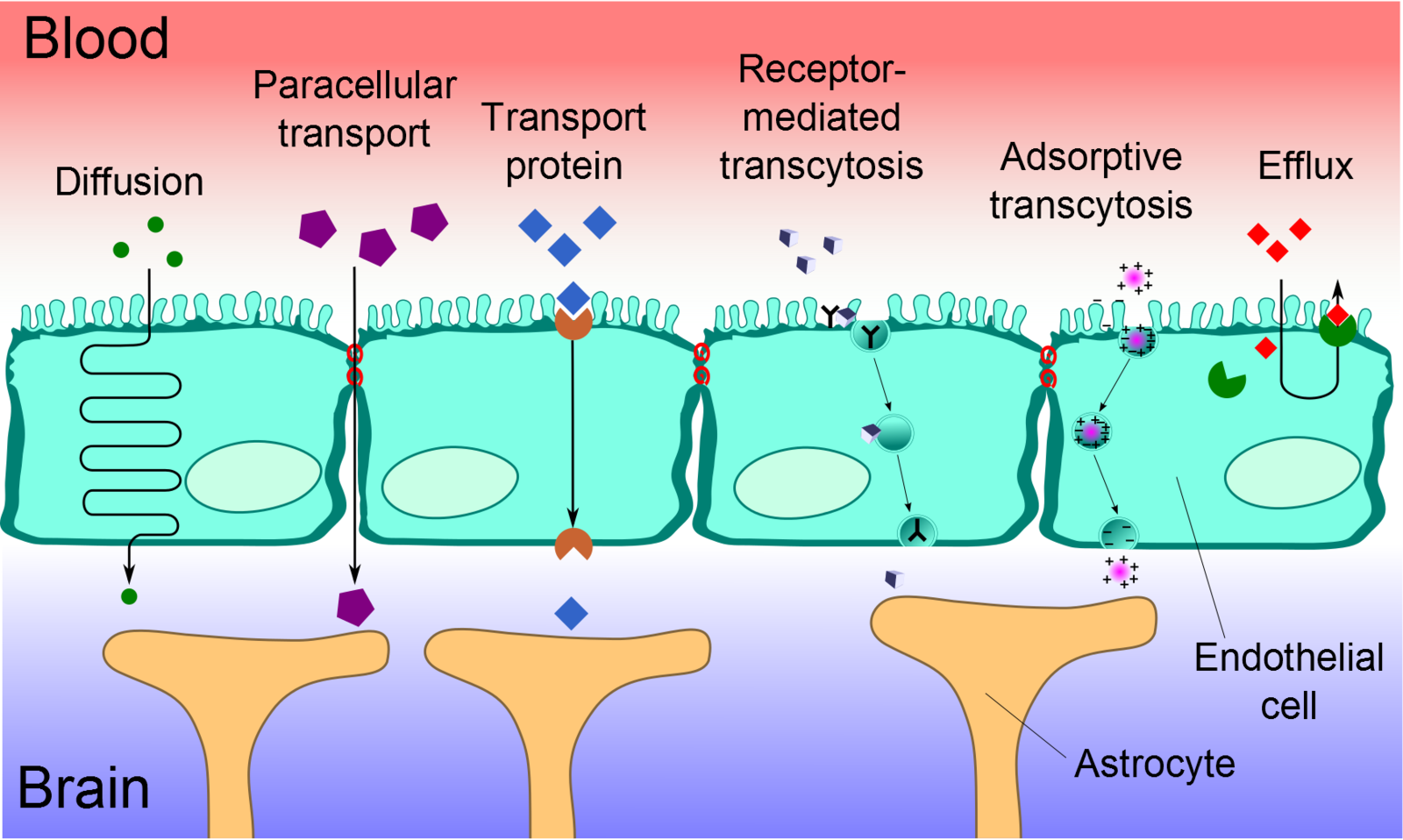

Cerebral capillary ECs are unique from peripheral capillary ECs in that they contain a significant number of tight junctions, have fewer cytoplasmic vesicles, and have a higher concentration of mitochondria. These tight junctions limit paracellular movement and divide the membranes of ECs into two distinct sides with different membrane compositions.[12] Several transport routes have been established to allow for the movement of molecules across the BBB to counteract this limitation of solute movement.[13] See Figure. Transport Processes at the Blood Brain Barrier.

Diffusion

The diffusion of substances into the brain is achieved via paracellular or transcellular pathways. To a minor extent, small water-soluble molecules can use simple diffusion to travel through the tight junctions of the BBB. Similarly, small lipid-soluble substances, such as alcohol or steroid hormones, can transcellularly penetrate the BBB via the dissolution of their lipid plasma membrane. For all other substances, including glucose and amino acids, specialized transport routes are needed to cross the BBB.[14]

Transport Proteins

Transport proteins are essential for specific solutes, such as glucose or amino acids, to cross the BBB. These solutes bind to a protein transporter on one side of the membrane, triggering a conformational change in the protein and the subsequent transport of the substance from high to low concentration. Should a charged compound need to be moved against the concentration gradient, ATP supplies the energy for this process.[14]

Efflux Pumps

Efflux pumps are responsible for expelling both endogenous and exogenous compounds, such as drugs, from the brain into the blood. Of particular importance, active drug efflux transporters of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) gene family are important determinants of drug distribution to and elimination from the CNS. This mechanism is seen as a significant obstacle in that it can limit the distribution of medications that are beneficial to treat CNS diseases.[15]

Receptor-Mediated Transcytosis (RMT)

Receptor-mediated transcytosis (RMT) allows for the selective uptake of macromolecules. Cerebral ECs have receptors for the uptake of specific molecules, including the insulin receptor, transferrin receptor, and lipoprotein transport receptor. Selective molecules bind to their receptors in clathrin-coated pits, specialized areas of the plasma membrane. These coated pits invaginate into the cytoplasm and are pinched free to form coated vesicles. The ligand can dissociate from the receptor once acidification of the endosome is complete and cross to the other side of the membrane.[16]

Adsorptive-Mediated Transcytosis (AMT)

Adsorptive-mediated transcytosis (AMT), also known as pinocytosis, is triggered by the interaction between a positively charged protein and the negatively charged surface of the plasma membrane. In essence, cationic molecules can bind to the luminal surface of endothelial cells and subsequently undergo exocytosis at the abluminal surface. The high mitochondrial content in cerebral endothelial cells provides the necessary means for the molecules to move through the endothelial cytoplasm.[17]

Cell-Mediated Transcytosis (CMT)

Cell-mediated transcytosis (CMT) is a well-established mechanism for pathogen entry into the brain via the "Trojan horse" model, which utilizes immune cells, such as macrophages and monocytes, to travel across the BBB. While the other previously mentioned transport pathways allow only molecules with specific properties to cross the BBB, CMT can be used for any type of molecule to cross the BBB. For example, HIV-infected cells utilize CMT via diapedesis through intact endothelial cells of the BBB. This route of transport has more recently been identified as a possible route of drug transport for pharmaceutical uses.[18]

Pathophysiology

As previously stated, dysfunction of the BBB can be seen in many chronic neurological disorders, such as multiple sclerosis (MS), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), Alzheimer disease (AD), and Parkinson disease (PD). BBB dysfunction may also be observed in acute neurological disorders such as traumatic brain injury (TBI) or stroke. It is currently known that cerebrovascular dysfunction (CVD) and vascular pathology play a significant role in the majority of these neurological disorders.[19]

Alzheimer Disease

A widely accepted hypothesis regarding the pathogenesis of AD is the two-hit vascular hypothesis, which states that while either oxidative stress or mitotic signaling abnormalities may independently serve as initiators of the disease, they are both needed to generate the disease pathology.[20]

The first hit in the two-hit hypothesis is damage to blood vessels. Damage may occur through vascular risk factors, such as diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia; environmental risk factors, such as pollution; or genetic risk factors, such as being a carrier of the APOE-ε4 gene. Blood vessel damage causes BBB dysfunction and decreased brain perfusion, which leads to the second hit in the two-hit hypothesis - Aβ accumulation in the brain. Aβ accumulation leads to neuronal injury and degeneration, synaptic dysfunction, and, ultimately, dementia.

Parkinson Disease

Parkinson disease (PD) is the second most common degenerative neurological disorder globally, second only to Alzheimer disease. Pathologically, PD is characterized by the degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta and the accumulation of α-synuclein inclusion bodies termed Lewy bodies. Risk factors for the development of PD include known genetic alterations and environmental risk factors, which may ultimately lead to neuronal death in PD.

Past studies related to the pathological process of PD stated that the BBB was not truly compromised in PD. The main reason the BBB was thought to be intact in PD patients was due to the use of peripheral aromatic amino acid decarboxylase (AAAD) inhibitors, such as carbidopa. The fact that carbidopa does not compromise levodopa therapy further contributed to this belief. Carbidopa was developed based on its inability to cross the BBB while effectively inhibiting the peripheral decarboxylase enzyme, thereby increasing the availability of levodopa, which can cross the BBB to the brain.[21]

However, as of 2020, further studies have shown that the BBB is disrupted in animal models of PD, yet clinical studies in humans are currently lacking. It is the current idea that PD involves the vascular model of neurodegeneration. The two concepts of this model are hypoperfusion and BBB disruption, both of which contribute to neuronal dysfunction and death. In humans, a small positron emission tomography (PET) study in PD patients showed dysfunction of the BBB transporter system. Furthermore, a histological examination revealed significantly increased permeability of the BBB in the post-commissural putamen of PD patients. Thus, the areas implicated in PD pathology have demonstrated BBB disruption, yet, as previously stated, studies remain few and predominantly in animal models.[22]

Traumatic Brain Injury

BBB disruption associated with TBI is considered a significant risk factor for high morbidity and mortality. The disruption of the BBB may occur within hours following injury and can persist from days to years. Two markers of BBB disruption, extravasation of the serum protein fibrinogen and immunoglobulin G (IgG), were observed in the brains of human patients that died in the acute phase following TBI, as well as in those that survived at least one year.

A significant consequence of BBB disruption associated with TBI is cerebral edema due to excess water accumulation in the brain. Two types of edema, cytotoxic and vasogenic, can occur following a brain injury. Vasogenic edema results from fluid accumulation in the perivascular space, leading to changes in cerebral blood flow (CBF) and increased intracranial pressure (ICP). Alternatively, cytotoxic edema is caused by the activation of ion channels that drive the influx of water into the intracellular space of various cell types resulting in further disruption to the BBB. Without immediate intervention, elevated ICP and changes in CBF can result in irreversible tissue damage and cell death, contributing to high mortality in severe cases of TBI.[23]

Clinical Significance

The structure, function, and dysfunction of the BBB are of significant importance in the discussion of CNS disorders and associated therapeutics. Very few drugs are successful in treating CNS diseases, with the therapeutic efficacy significantly limited by two significant challenges, the first being ineffective transportation of drugs across the BBB. The efficiency of drug transportation across the BBB dramatically depends on the properties of molecular size, hydrophilicity, and degree of dissociation. Currently, it is known that most small-molecule drugs and almost all macromolecular drugs, such as recombinant proteins, therapeutic antibodies, and nucleic acids, cannot cross the BBB. Therefore, developing a drug delivery system that can effectively transport therapeutic agents into the CNS is crucial in the future treatment of CNS diseases.[14]

The second challenge the BBB poses, which limits therapeutic efficacy, is that diseases causing focal BBB breakdown lead to perivascular accumulation of blood-derived toxic products and macromolecules, inflammatory responses, vascular regression, and local reductions of CBF. These focal vascular changes limit the CNS distribution of neurotherapeutics in disease-affected regions by disrupting diffusional transport across brain endothelial cells, blocking normal interstitial flow dynamics, or both.[24]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Transport Processes at the Blood Brain Barrier

Kuebi= Armin Kübelbeck, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

References

Daneman R, Prat A. The blood-brain barrier. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology. 2015 Jan 5:7(1):a020412. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a020412. Epub 2015 Jan 5 [PubMed PMID: 25561720]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDong X. Current Strategies for Brain Drug Delivery. Theranostics. 2018:8(6):1481-1493. doi: 10.7150/thno.21254. Epub 2018 Feb 5 [PubMed PMID: 29556336]

Zhao Z, Nelson AR, Betsholtz C, Zlokovic BV. Establishment and Dysfunction of the Blood-Brain Barrier. Cell. 2015 Nov 19:163(5):1064-1078. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.067. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26590417]

Hall CN, Reynell C, Gesslein B, Hamilton NB, Mishra A, Sutherland BA, O'Farrell FM, Buchan AM, Lauritzen M, Attwell D. Capillary pericytes regulate cerebral blood flow in health and disease. Nature. 2014 Apr 3:508(7494):55-60. doi: 10.1038/nature13165. Epub 2014 Mar 26 [PubMed PMID: 24670647]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMajesky MW. Developmental basis of vascular smooth muscle diversity. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2007 Jun:27(6):1248-58 [PubMed PMID: 17379839]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceObermeier B, Daneman R, Ransohoff RM. Development, maintenance and disruption of the blood-brain barrier. Nature medicine. 2013 Dec:19(12):1584-96. doi: 10.1038/nm.3407. Epub 2013 Dec 5 [PubMed PMID: 24309662]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceEngelhardt B, Liebner S. Novel insights into the development and maintenance of the blood-brain barrier. Cell and tissue research. 2014 Mar:355(3):687-99. doi: 10.1007/s00441-014-1811-2. Epub 2014 Mar 4 [PubMed PMID: 24590145]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKiecker C. The origins of the circumventricular organs. Journal of anatomy. 2018 Apr:232(4):540-553. doi: 10.1111/joa.12771. Epub 2017 Dec 27 [PubMed PMID: 29280147]

Kaur C, Ling EA. The circumventricular organs. Histology and histopathology. 2017 Sep:32(9):879-892. doi: 10.14670/HH-11-881. Epub 2017 Feb 8 [PubMed PMID: 28177105]

Absinta M, Ha SK, Nair G, Sati P, Luciano NJ, Palisoc M, Louveau A, Zaghloul KA, Pittaluga S, Kipnis J, Reich DS. Human and nonhuman primate meninges harbor lymphatic vessels that can be visualized noninvasively by MRI. eLife. 2017 Oct 3:6():. doi: 10.7554/eLife.29738. Epub 2017 Oct 3 [PubMed PMID: 28971799]

Zeisel A, Muñoz-Manchado AB, Codeluppi S, Lönnerberg P, La Manno G, Juréus A, Marques S, Munguba H, He L, Betsholtz C, Rolny C, Castelo-Branco G, Hjerling-Leffler J, Linnarsson S. Brain structure. Cell types in the mouse cortex and hippocampus revealed by single-cell RNA-seq. Science (New York, N.Y.). 2015 Mar 6:347(6226):1138-42. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa1934. Epub 2015 Feb 19 [PubMed PMID: 25700174]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceZaragozá R. Transport of Amino Acids Across the Blood-Brain Barrier. Frontiers in physiology. 2020:11():973. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2020.00973. Epub 2020 Sep 23 [PubMed PMID: 33071801]

Abbott NJ, Romero IA. Transporting therapeutics across the blood-brain barrier. Molecular medicine today. 1996 Mar:2(3):106-13 [PubMed PMID: 8796867]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChen Y, Liu L. Modern methods for delivery of drugs across the blood-brain barrier. Advanced drug delivery reviews. 2012 May 15:64(7):640-65. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2011.11.010. Epub 2011 Nov 28 [PubMed PMID: 22154620]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLöscher W, Potschka H. Blood-brain barrier active efflux transporters: ATP-binding cassette gene family. NeuroRx : the journal of the American Society for Experimental NeuroTherapeutics. 2005 Jan:2(1):86-98 [PubMed PMID: 15717060]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePulgar VM. Transcytosis to Cross the Blood Brain Barrier, New Advancements and Challenges. Frontiers in neuroscience. 2018:12():1019. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2018.01019. Epub 2019 Jan 11 [PubMed PMID: 30686985]

Hervé F, Ghinea N, Scherrmann JM. CNS delivery via adsorptive transcytosis. The AAPS journal. 2008 Sep:10(3):455-72. doi: 10.1208/s12248-008-9055-2. Epub 2008 Aug 26 [PubMed PMID: 18726697]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLorin V, Danckaert A, Porrot F, Schwartz O, Afonso PV, Mouquet H. Antibody Neutralization of HIV-1 Crossing the Blood-Brain Barrier. mBio. 2020 Oct 20:11(5):. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02424-20. Epub 2020 Oct 20 [PubMed PMID: 33082263]

Sweeney MD, Sagare AP, Zlokovic BV. Blood-brain barrier breakdown in Alzheimer disease and other neurodegenerative disorders. Nature reviews. Neurology. 2018 Mar:14(3):133-150. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2017.188. Epub 2018 Jan 29 [PubMed PMID: 29377008]

Zhu X, Lee HG, Perry G, Smith MA. Alzheimer disease, the two-hit hypothesis: an update. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2007 Apr:1772(4):494-502 [PubMed PMID: 17142016]

Desai BS, Monahan AJ, Carvey PM, Hendey B. Blood-brain barrier pathology in Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease: implications for drug therapy. Cell transplantation. 2007:16(3):285-99 [PubMed PMID: 17503739]

Al-Bachari S, Naish JH, Parker GJM, Emsley HCA, Parkes LM. Blood-Brain Barrier Leakage Is Increased in Parkinson's Disease. Frontiers in physiology. 2020:11():593026. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2020.593026. Epub 2020 Dec 22 [PubMed PMID: 33414722]

Cash A, Theus MH. Mechanisms of Blood-Brain Barrier Dysfunction in Traumatic Brain Injury. International journal of molecular sciences. 2020 May 8:21(9):. doi: 10.3390/ijms21093344. Epub 2020 May 8 [PubMed PMID: 32397302]

Sweeney MD, Zhao Z, Montagne A, Nelson AR, Zlokovic BV. Blood-Brain Barrier: From Physiology to Disease and Back. Physiological reviews. 2019 Jan 1:99(1):21-78. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00050.2017. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30280653]