Introduction

Orbital compartment syndrome (OCS) is caused due to rapidly increasing intra-orbital pressure and can lead to permanent blindness. OCS is a sight-threatening condition, originally described by Gordan and McRae in 1950 in a case following zygoma fracture repair. OCS is secondary to ischemia of the optic nerve and related retinal function, and a lack of perfusion can lead to irreversible loss of vision. OCS is a type of compartment syndrome, and as with other compartment syndromes, rapidly increasing intra-compartment pressures are related to significant morbidity and permanent damage.[1]

OCS occurs as a result of mass effect within the confines of the orbit; any process that can cause an increase in intraorbital pressure can lead to OCS. Intraorbital pressures can increase due to both hemorrhage and non-hemorrhagic processes, such as fluid accumulation. Non-traumatic causes of hemorrhage include iatrogenic procedures such as orbital, eyelid, and lacrimal surgeries. Orbital hemorrhage can also be caused by commonly used anesthetic procedures such as peribulbar or retrobulbar injections of localized anesthetics. Valsalva-related hemorrhage in the setting of sinonasal carcinoma, orbital-lymphatic malformation-related hemorrhages, extraocular tumors causing metastases has also been demonstrated as causes of OCS.[1]

Non-hemorrhagic causes of OCS include processes such as prolonged prone surgery (such as spinal surgery), facial and periocular burns, and massive fluid resuscitation for severe burns, all of which can lead to third-spacing of fluid within the orbital compartment. Uncommon causes of OCS include orbital emphysema in the setting of associated paranasal sinus fractures.[1]

All emergency physicians must also be wary of orbital cellulitis, regardless of the presence of an associated abscess, as a possible cause of OCS.[1]

OCS is a serious ophthalmologic emergency, regardless of etiology, and all emergency physicians should be able to clinically diagnose this condition and have an understanding of lateral orbital canthotomy and cantholysis (LOC) procedure in order help prevent permanent vision loss. OCS can lead to proptosis of the globe, which leads to stretch tension on the optic nerve in addition to the compressive forces of the intra-compartment pressure. The goal of LOC is to free the eyelid from its lateral attachment to the bony orbit, thus releasing the pressure that has accumulated within the closed orbital compartment.[2]

While emergent ophthalmologic consultation is ideal for intervention, optic nerve ischemia due to OCS can develop very rapidly. Improved visual outcomes can be achieved if interventions such as LOC are performed promptly (ideally within 2 hours of presentation).[3]

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

The orbital cavity is a pyramid-shaped, 30 mL, a four-sided enclosure that houses the globe. The superior and inferior orbital septa are located anteriorly, and the cavity is made up of seven bones. The medial and inferomedial borders are made of the maxilla, inferolateral and lateral borders are made of the zygomatic bone, the superolateral, superior, and superomedial borders are made of the frontal bone. The ethmoid and lacrimal bones comprise the posteromedial borders, the palatine bone consists of a very small portion of the posterior orbital wall, whereas the rest of the posterior and posterolateral walls are made of the sphenoid bones.[4]

Within the bony cavity, the globe has a 7 mL volume and is tethered in the cavity posteriorly by the optic nerve and the ophthalmic artery; this tethering limits the forward movement of the globe. Anterior globe displacement is prevented by the medial and lateral canthal tendons, which are muscular insertions attaching the muscular layer of the eyelids to the bony cavity of the orbit. These tendons are often also known as medial and lateral palpebral ligaments. The superior and inferior canthal ligaments attach the tissues of the interior of the eyelids to the orbital periosteum.[4]

Of note: the lateral canthal raphe is superior to the lateral canthal tendon, and is slightly separated from the fibrous fascial plane of the lateral canthal tendon.[4]

The natural shape of the open eyelid, dictated by the articular edges, form palpebral fissure. The medial and lateral canthi are junctions of the upper and lower eyelids at the extremes on each side of the palpebral fissure. Each eyelid is formed by tarsal plates, which are dense fibrous bands running the length of the medial and lateral bony orbit. Each tarsal plate is attached posteriorly to the conjunctiva. Altogether, the combination of the globe and tarsal plate with their associated insertions comprise the anterior border of the orbit. As described above, the posterior lateral and medial borders of the orbit are formed by bones.[5]

Indications

Since OCS is a clinical diagnosis, and the risk of irreversible blindness is great, any patient with facial trauma, infectious process of the sinus or orbit, concern for retrobulbar hemorrhage or recent ophthalmologic surgery who presents with proptosis, decreased visual acuity, elevated intraocular pressures (IOP), restricted extraocular muscle movement, and/or afferent pupillary defect should be considered for emergent lateral orbital canthotomy with cantholysis.[5]

Intraocular pressure measurements of 40 mmHg or higher indicate a soft threshold for intervention. For patients that are unconscious with periorbital injury or who are unconscious and unable to give a history or describe their symptoms and participate in a physical examination, an emergent lateral canthotomy is indicated.[5]

Contraindications

Globe Rupture, whether suspected clinically and suggested by enophthalmos as opposed to proptosis or confirmed through a CT scan image is a contraindication to the lateral orbital canthotomy.[5]

Equipment

To successfully perform a lateral orbital canthotomy, the following equipment is needed: betadine prep for sterilizing the area, then a sterile drape over the affected side.[6] For anesthesia, local anesthetic such as 1% to 2% lidocaine with epinephrine can be used. To flush or irrigate the area, normal saline or sterile water can be used. A hemostat will be used to establish hemostasis and as a way to crimp the skin to establish a landmark. Finally, forceps to raise the skin and either scissors or a scalpel with a #10 blade can be used; however, a scissor is preferred as it helps the physician establish normal control. All of these tools can be found in standard laceration repair trays.[7]

Personnel

While ophthalmologists are the preferred physicians to perform this procedure, other physicians who have experiences with bedside surgical procedures such as emergency medicine physicians, trauma surgeons, general surgeons, or OMF (oral and maxillofacial) surgeons can perform this procedure. While an assistant is preferred to help pass materials along and ensure safety, LOC can be performed safely and in a sterile manner by just one physician.

Preparation

In addition to gathering all the above equipment as listed, there is little additional preparation required for this emergent bedside procedure. In addition to focused lighting, if there is significant bleeding or dry blood, cleaning the area to best visualize all landmarks is the most important step. The patient should be placed prone, lying flat in bed, and sedated if time allows.[6]

Technique or Treatment

The vision-saving procedure of lateral orbital canthotomy and Cantholysis can be done rapidly, in a brief, step-wise fashion.[7] The steps are outlined as follows:

- Begin by anesthetizing the site of the incision. Using a 25-gauge needle, inject approximately two milliliters of 1% to 2% lidocaine with epinephrine into the lateral canthus, pointing away from the globe, in the affected eye.

- As the local anesthetic takes effect, use normal saline to irrigate and flush any debris and foreign objects from the canthus and eye. Use caution to avoid any trauma to the globe point away from it.

- Use a hemostat to gently crimp the lateral corner of the inferior eyelid. This step serves two functions: it will help establish the landmark for where to eventually cut, but also make the skin thinner for an easier incision.

- Raise the skin around the aforementioned landmark using forceps or atraumatic shears while simultaneously using a surgical blade or scissor to make a 1 to 2 cm incision at the landmark. The incision should be made from the lateral canthus and should be extended laterally.

- Use the blunt dissection technique until all tissue is out of the way, and the lateral canthal tendon is identified.

- Once the inferior crus of the lateral canthal tendon is identified, redirect the surgical blade or scissors inferiorly and strum the tendon. Once the tendon is strummed, cut the fibers of the tendon until complete laxity of the lower eyelid is achieved.2

- Recheck the intraocular pressure. If the pressure is still elevated, this procedure can be repeated on the superior crus of the lateral canthal tendon.

Following these steps should immediately relieve intraocular pressure. Visual acuity can improve shortly after the procedure; however, final visual acuity is dependent on the degree of irreversible damage that occurred prior to intervention.[6]

Complications

There are five main complications associated with an emergency lateral orbital canthotomy: incomplete cantholysis, iatrogenic globe rupture or surrounding structure injury (rare), loss of adequate lower lid suspension, and subsequent eyelid mispositioning, infection and bleeding.[6]

Iatrogenic globe injury and/or rupture from the instruments, such as forceps, scissors, surgical blades, or hemostat, used for the procedure is a possible complication of this injury. Additional complications include ptosis, which can occur due to damage to levator aponeurosis and Müller’s muscle, which are located superiorly in the orbital cavity. Injury to the lacrimal gland and Meibomian glands are possible complications as these are located superiorly in the orbital cavity.[6]

Less common complications include bleeding and infection. As with any surgical procedure, there is a risk of infection from accessing parts of the eyes from iatrogenic rupture of the barrier, as well as through instrumentation in that area. Bleeding is another common risk of a surgical procedure. In this case, injury to the lacrimal artery can cause severe bleeding, along with possible incision to other vasculature in the area.[6]

Clinical Significance

All patients who present within two hours of insult with complaints of unilateral vision loss causing concern for OCS should undergo emergent lateral orbital canthotomy to achieve maximal benefits of the intervention, as a prompt intervention within the first two hours leads to improved chances of visual recovery.[8] In a case report from Denmark, an 80-year old man who slipped and fell, suffering a left lateral blowout orbital fracture who complained of loss of vision and two-and-a-half hours later developed unilateral protrusion of 8mm, taut orbital septum, dilated left pupil, EOM motility limited to 5% to 10%, absence of light perception and tonometry measurement of 62 mmHg (compared to 20 mmHg in the unaffected side), lateral orbital canthotomy led to significant improvement.[9] Five minutes after the procedure, the patient was able to detect hand movement, 25 minutes later, the patient was able to count fingers, and after thirty minutes, tonometry revealed intraocular pressure (IOP) of 26 mmHg and very mildly limited EOM. The lateral canthal ligament was sutured after two days, and after five days, edema and protrusion were absent, tonometry revealed an IOP of 18 mmHg, and visual acuity was nearly restored. At 6 months follow-up, the patient’s only complaints were mild color desaturation in the left eye.

Another case report from Philadelphia details the importance of emergent intervention as it demonstrates the restoration of visual acuity. A 45-year-old man who suffered assault with a blunt object and presented to the emergency department with multiple facial injuries complaining of severe pain in the right eye with associated decreased visual acuity, and on examination had a Grade IV hyphema, 360-degree subconjunctival hemorrhage with proptosis, limited extraocular muscles (EOM) and visual acuity testing revealed no light perception. Tonometry measurements revealed an IOP of 79 mmHg, and a non-contrast CT scan revealed a retrobulbar hemorrhage on the right without evidence of globe rupture. Emergent ophthalmology consultation revealed that the physician was nearly two hours away, so an immediate and emergent lateral orbital canthotomy was performed. Immediately after the procedure, the patient reported improvement in pain, and IOP decreased to 35 mmHg. After inpatient management of injuries, the discharge examination revealed visual acuity of 20/40 in the affected eye.[5]

A 2019 case report describes similarly positive outcomes in patients who present to the emergency department with signs of OCS and timely intervention by emergency medicine physicians. A 32-year-old man who was assaulted presented to the emergency department one hour after with periorbital swelling, proptosis, and complaints of decreased vision. A non-contrast CT scan revealed exophthalmos, abnormal caliber, and density of optic nerve sheath and a pre-septal hematoma, without other intracranial injuries or fractures. In this case, because the patient was complaining of near-vision loss, a lateral orbital canthotomy was performed to transfer the patient to ophthalmology service for further care. Overnight, the patient regained full vision in his eye and was discharged the following day with ophthalmology follow-up.[7]

While the lateral orbital canthotomy and cantholysis procedure is best performed by ophthalmologists, the need for timely intervention and threat of permanent vision loss may preclude the ability to wait for ophthalmology services. All emergency medicine physicians must feel comfortable with this procedure, as it can be performed safely, quickly, and emergently to prevent irreversible vision loss. As described in a 2019 article in the American Journal of Emergency Medicine by Fox et. al.[10], the primary management of orbital compartment syndrome is lateral orbital canthotomy and cantholysis, a procedure that is not recognized by the American College of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) as an essential skill to become a board-certified emergency physician. Numerous suboptimal outcomes in patient with OCS have been directly attributed to a knowledge gap in the diagnosis and management of OCS, and lack of knowledge and confidence by emergency medicine physicians in performing this sight-saving procedure.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Orbital compartment syndrome (OCS) is a vision-threatening condition, which is best diagnosed clinically, and the definitive treatment is lateral orbital canthotomy (LOC) and cantholysis. Irreversible vision loss can be avoided if LOC is performed within the first two hours of the patient’s presentation.[8] Most often, these procedures are performed by the consulting ophthalmologist, but often the acuity of the patient’s injuries, deteriorating visual acuity, unavailability of the ophthalmologist due to other commitments leads to suboptimal outcomes if the procedure is not performed in a timely fashion. Therefore, widespread training of LOC amongst all the physicians in the healthcare team, especially emergency medicine (EM) physicians, can lead to improved outcomes for patients with OCS.

While EM physicians are first to encounter patients with potential OCS, a 2019 prospective cohort study on the management of OCS by non-ophthalmologic EM physicians demonstrated that 82.8% of participating physicians were able to diagnose the ophthalmologic emergency, and an overwhelming 78.7% indicated that they would first perform a diagnostic computed tomography (CT) scan. Only 37.1% reported that they would perform LOC themselves, and 92.2% indicated that they would not perform the procedure themselves is because they believed they needed more training in diagnosing OCS and performing LOC. This demonstrates a need for a healthcare-based approach to the importance of collaboration between ophthalmologists and emergency physicians in training together to lead to better outcomes for the patients.[11] [Level 3]

While emergency medicine physicians are not required to be certified in LOC as per American Counsel of Graduate Medical Education’s (ACGME) training curriculum, training for LOC in EM physicians and general surgeons can avoid permanent loss of vision in patients with OCS. A 2019 randomized control study by the Association of Military Surgeons of the United States demonstrated that synthetic models are comparable to swine models for the training for LOC. Synthetic models can be produced and distributed widely, and incorporation of LOC in the training of all EM physicians by ACGME will lead to improved outcomes for patients.[12] [Level 2]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Retrobulbar Hematoma. The patient developed severe pain in the left eye and orbit after an uneventful upper blepharoplasty. The patient was not seen and examined until the following morning when this photograph was taken. The patient has no perception of light in the left eye. A canthotomy, cantholysis, and evacuation of orbital hemorrhage did not help this patient, as this should have been performed much earlier.

Contributed by Prof. BCK Patel MD, FRCS

(Click Image to Enlarge)

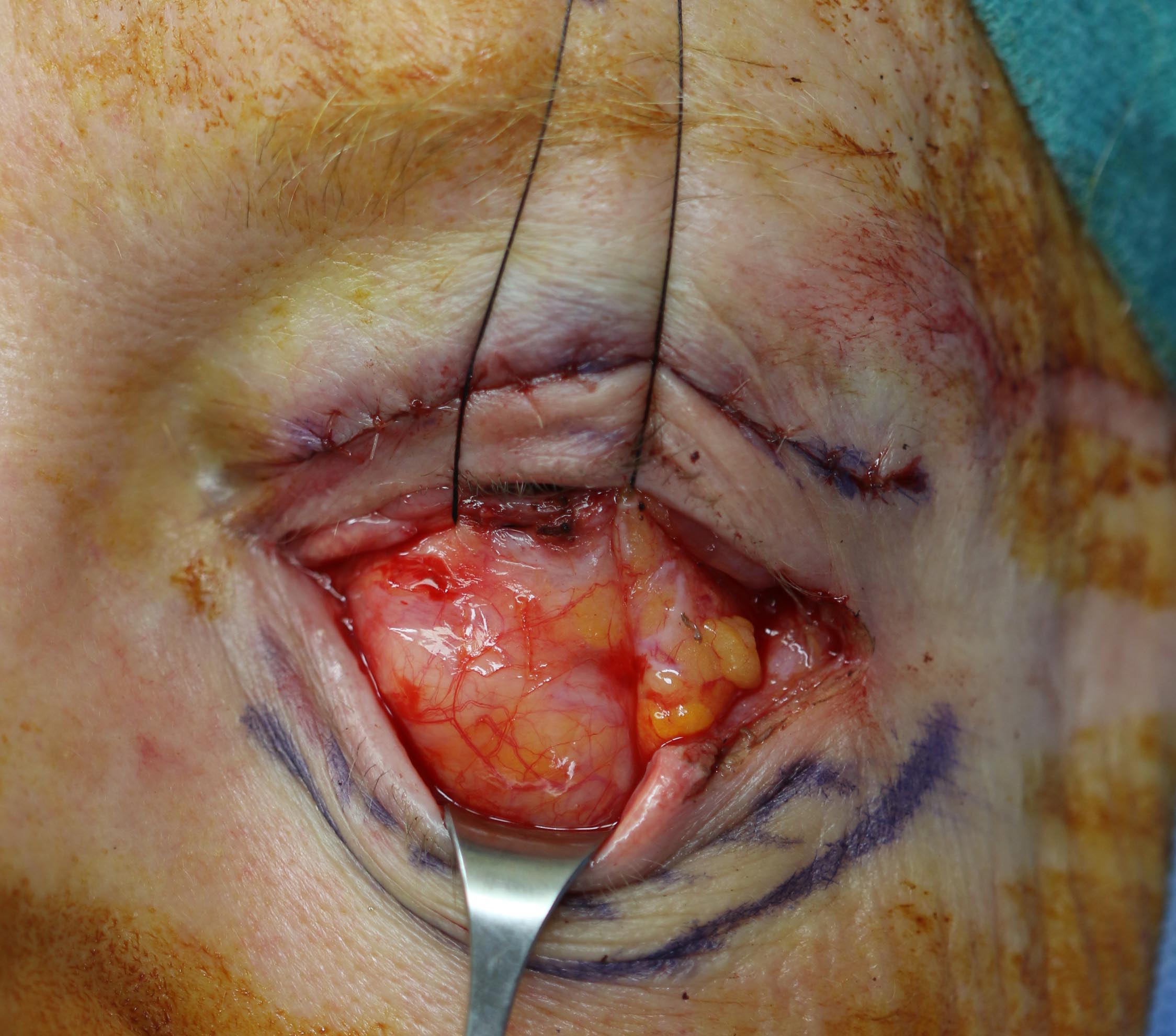

A transconjunctival blepharoplasty being performed with a lateral canthotomy and cantholysis illustrating the medial, the central and lateral fat pads. The medial and central fat pads may sometimes appear to be contiguous as seen here. The lateral fat pad is usually higher and lateral and is the fat pad that is often under corrected with trans conjunctival blepharoplasty approaches. Contributed by Prof. Bhupendra C.K. Patel MD, FRCS

References

McCallum E, Keren S, Lapira M, Norris JH. Orbital Compartment Syndrome: An Update With Review Of The Literature. Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, N.Z.). 2019:13():2189-2194. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S180058. Epub 2019 Nov 7 [PubMed PMID: 31806931]

Amer E, El-Rahman Abbas A. Ocular Compartment Syndrome and Lateral Canthotomy Procedure. The Journal of emergency medicine. 2019 Mar:56(3):294-297. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2018.12.019. Epub 2019 Jan 21 [PubMed PMID: 30679067]

Soare S, Foletti JM, Gallucci A, Collet C, Guyot L, Chossegros C. Update on orbital decompression as emergency treatment of traumatic blindness. Journal of cranio-maxillo-facial surgery : official publication of the European Association for Cranio-Maxillo-Facial Surgery. 2015 Sep:43(7):1000-3. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2015.05.003. Epub 2015 May 29 [PubMed PMID: 26116304]

Iserson KV, Luke-Blyden Z, Clemans S. Orbital Compartment Syndrome: Alternative Tools to Perform a Lateral Canthotomy and Cantholysis. Wilderness & environmental medicine. 2016 Mar:27(1):85-91. doi: 10.1016/j.wem.2015.09.002. Epub 2015 Nov 12 [PubMed PMID: 26585073]

Rowh AD, Ufberg JW, Chan TC, Vilke GM, Harrigan RA. Lateral canthotomy and cantholysis: emergency management of orbital compartment syndrome. The Journal of emergency medicine. 2015 Mar:48(3):325-30. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2014.11.002. Epub 2014 Dec 16 [PubMed PMID: 25524455]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMcInnes G, Howes DW. Lateral canthotomy and cantholysis: a simple, vision-saving procedure. CJEM. 2002 Jan:4(1):49-52 [PubMed PMID: 17637149]

Houck J, Mangal R, Vandillen C, Ganti L, Sleigh BC. Orbital Compartment Syndrome: How a Young Man's Vision was Saved by the Timely Actions of an Emergency Medicine Physician. Cureus. 2019 Jul 1:11(7):e5057. doi: 10.7759/cureus.5057. Epub 2019 Jul 1 [PubMed PMID: 31516769]

Sun MT, Chan WO, Selva D. Traumatic orbital compartment syndrome: importance of the lateral canthomy and cantholysis. Emergency medicine Australasia : EMA. 2014 Jun:26(3):274-8. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.12236. Epub 2014 May 8 [PubMed PMID: 24810151]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLarsen M, Wieslander S. Acute orbital compartment syndrome after lateral blow-out fracture effectively relieved by lateral cantholysis. Acta ophthalmologica Scandinavica. 1999 Apr:77(2):232-3 [PubMed PMID: 10321547]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFox A, Janson B, Stiff H, Chung A, Benage M, Van Heukelom J, Oetting TA, Shriver EM. A multidisciplinary educational curriculum for the management of orbital compartment syndrome. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2020 Jun:38(6):1278-1280. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2019.12.002. Epub 2019 Dec 9 [PubMed PMID: 31987744]

Edmunds MR, Haridas AS, Morris DS, Jamalapuram K. Management of acute retrobulbar haemorrhage: a survey of non-ophthalmic emergency department physicians. Emergency medicine journal : EMJ. 2019 Apr:36(4):245-247. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2018-207937. Epub 2019 Jan 10 [PubMed PMID: 30630842]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHerder PAP, Lu MM, LaPorta AJ, Ross DW, Calvano CJ, Enzenauer RW. Comparison of a Novel Trainer to a Traditional Swine Model for Training Providers in Lateral Canthotomy and Cantholysis. Military medicine. 2019 Mar 1:184(Suppl 1):342-346. doi: 10.1093/milmed/usy389. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30901413]