Introduction

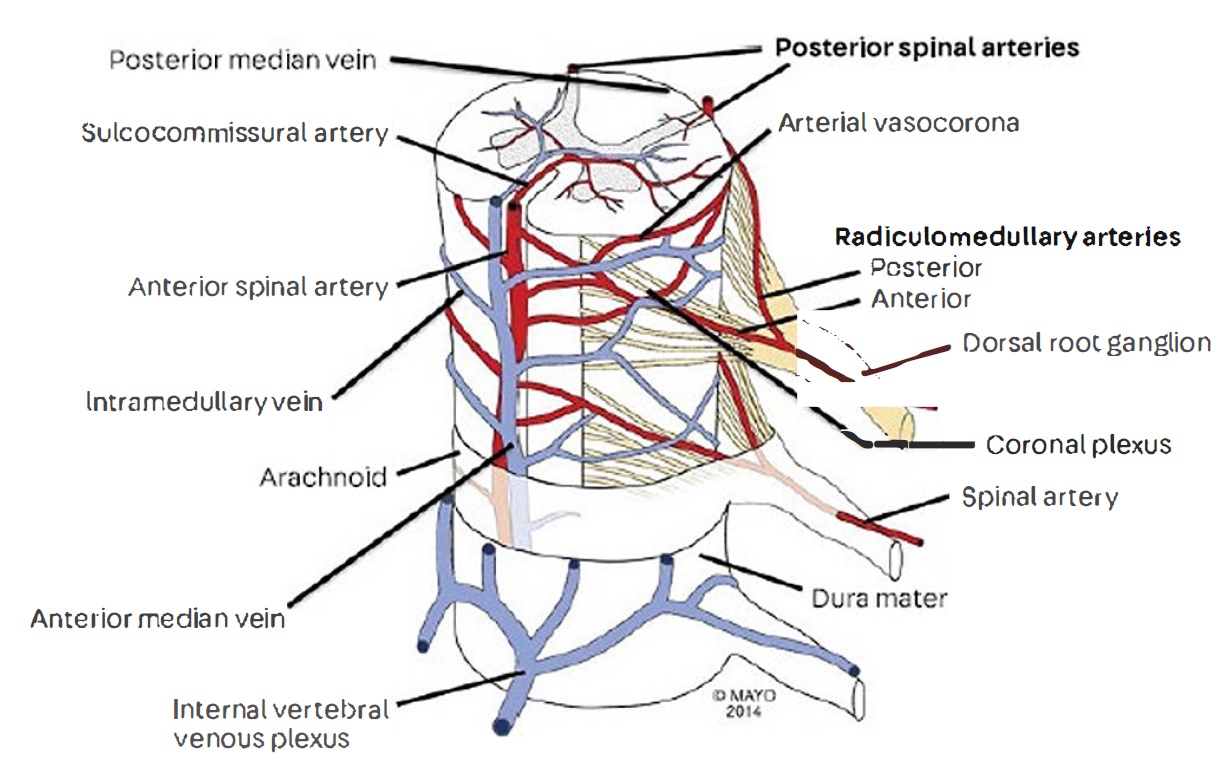

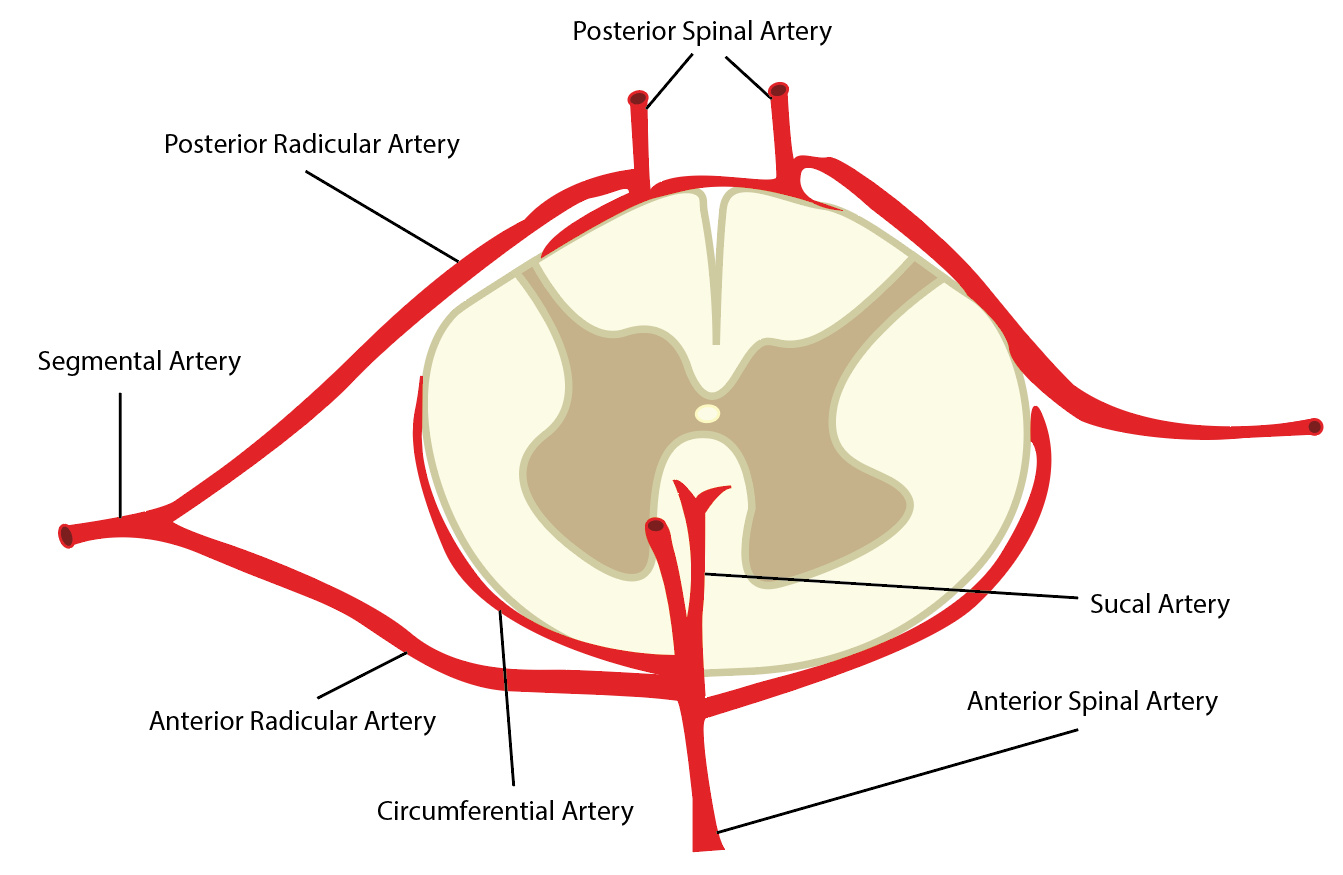

The spinal cord receives vascular supply through three major arteries. The single anterior spinal artery and two paired posterior spinal arteries. Segmented medullary arteries are supplied by the unbranched arteries that join the anterior spinal artery or the posterior spinal artery compared to radicular arteries that supply the nerve roots.[1]

Embryology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Embryology

Most radicular arteries disappear before birth; however, several dominant radiculomedullary ones remain, including the artery of Adamkiewicz. They also result in important collateral vessels for the spinal cord by forming anastomoses with the anterior and two posterior spinal arteries resulting in their common name of booster/feeder vessels.[1]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The cord is dependent upon three longitudinal arterial trunks or channels. The anterior and posterior spinal artery longitudinally runs along the whole spinal cord and often anastomose with each other forming plexuses.

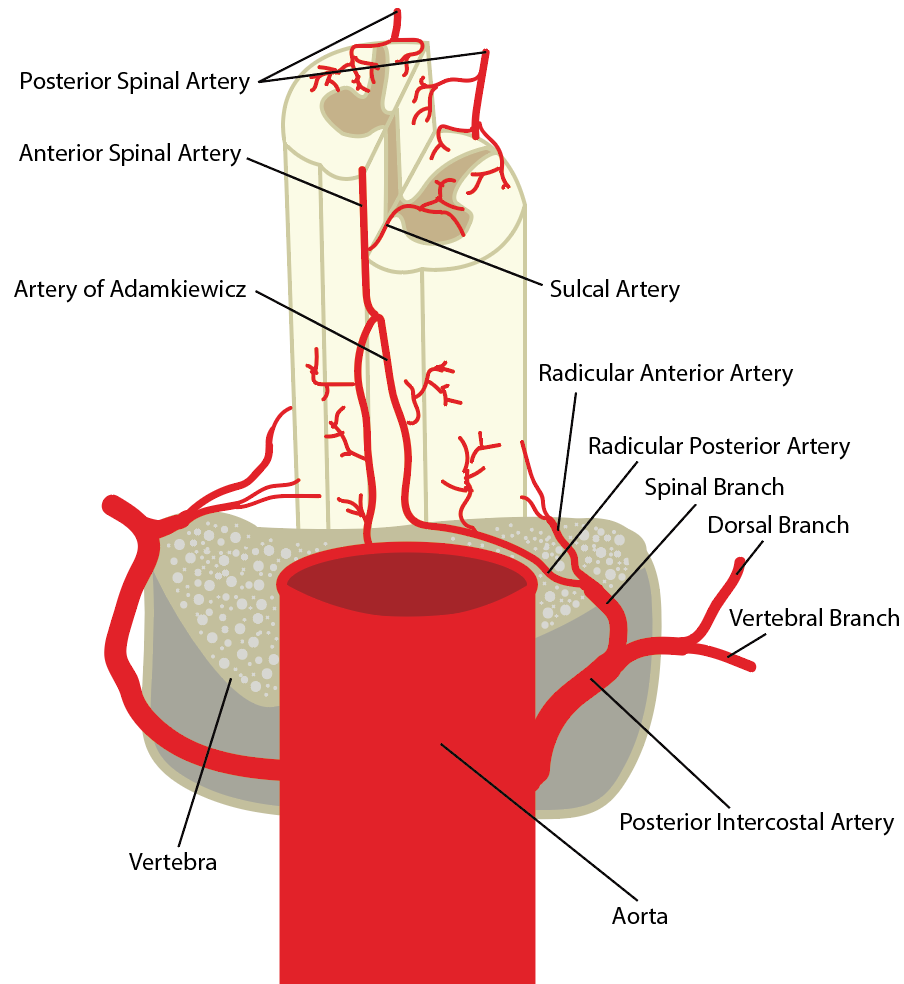

- The anterior and posterior spinal arteries receive supply via the vertebral arteries only up to the cervical segments of the spinal cord. Inferiorly the spinal arteries receive blood through the lumbar and radicular arteries.

- Anterior spinal artery (ASA)[2]:

- Runs the length of the spinal cord longitudinally along the anterior median fissure

- Primary blood supply of anterior two-thirds of the spinal cord

- The diameter of the ASA through the thoracic spinal cord is notably narrower when compared to its size in the cervical and lumbar regions. Thus, much of the blood flow to the thoracic spine derives from segmental arteries branching from the dorsal aorta.

- The anterior artery supplies the motor tracts and forms from the fusion of the vertebral arteries and receives reinforcement of blood supply from 6 to 8 radicular arteries.

- Posterior spinal artery (right and left):

- Run longitudinally on each side of the midline of the posterolateral sulcus consistently through the length of the spinal cord

- The two posterior spinal arteries originate directly from the vertebral arteries and are the primary blood supply to the posterior columns, dorsal grey matter, dorsal sensory columns - these arteries are often found to be discontinuous, and occasionally one artery will move across to supply the opposite side.

- It is useful to think of the posterior spinal artery as a plexus as it often anastomoses with the contralateral posterior spinal artery and may receive anastomoses with the anterior spinal artery via a plexus that encases the cord.

- Artery of Adamkiewic:

- It is the largest anterior radiculomedullary artery of that individual, contributing to its significant variation of location - it is also the largest anterior segmental artery.

- It typically arises from the left posterior intercostal artery and is the only significant arterial supply feeding the anterior spinal artery along the lower thoracic, lumbar, and sacral spinal cord.

- Due to its atypical nature, the artery of Adamkiewicz typically arises from the left side of the aorta between T8 and L2 in 75% of people, although it is important to realize that the artery of Adamkiewicz can also be present above T8 in about 20% of people - other less common variations exist, and collateral circulation with lumbar arteries exist.

- Other unnamed radicular arteries exist that also supply an important collateral support network.

- Anterior spinal artery (ASA)[2]:

Nerves

Cord ischemia, primarily secondary to vascular insults in the mid-thoracic region, is common as the diameter of the spinal cord and its resulting arteries undergo significant narrowing here. Damage of any kind to the anterior spinal artery can cause significant motor symptoms, as it supplies the anterior two-thirds of the spinal cord. The majority of the corticospinal tracts responsible for motor function are also affected by insults to the anterior spinal artery. In comparison, ischemia to the posterior spinal artery results in a sensory and proprioceptive loss due to its supply to the dorsal roots.

Muscles

Muscles have little to no effect on the spinal cord supply except in the case of minor anastomoses, as there is an extensive network of epidural arterial and minor vessels that supply the paraspinal musculature. These vessels are interconnected and anastomose with the subclavian arteries cranially and the lumbar/hypogastric arteries caudally. These anastomoses are especially useful in providing a minor collateral network that can supply some flow to the spinal cord in the occlusion of the larger routes.

Physiologic Variants

Variations in the origins, course, and position are common. However, variations of size are not.

Anomalies during embryology development, such as in angiogenesis, can cause[3][4]:

- Hypoplasia - Underdevelopment of the radicular arteries is most common.

- Atresia - as part of the VACTERL association

- Agenesis - Failure of an organ or associated vertebral component to form

- Absence - The absence of certain anastomoses can be due to embryological variation

- Duplication - Redundancy in specific the vertebral artery or certain radicular arteries can be present

- Fenestration - of the vertebral artery is considered to be an anastomosis abnormality occurring during embryologic development often associated with aneurysms

Surgical Considerations

The thoracic spine from T2 to T10 has increased stiffness due to intervertebral disks, coronal plane articulation of the facet joints, and articulation with the ribs, which in turn articulate with the sternum. The inherent kyphosis in the thoracic spine also concentrates the axial load on the anterior column improving rigidity. Therefore, fractures are generally less common. However, it is increasingly worrisome when they do occur since the mid-thoracic spine is a known vascular watershed area. During surgical exposure, extensive dissection and periosteal stripping should be avoided around the mid-thoracic region since even minor vascular insults can lead to cord ischemia.[5]

The artery of Adamkiewicz is the only significant arterial supply feeding the anterior spinal artery along the lower thoracic, lumbar, and sacral spinal cord. This vessel is clinically relevant, as injury to this vital artery can occur during various procedures, most notably descending/thoracoabdominal aortic repairs. Injury to this artery can cause consequential neurologic damage manifesting as anterior spinal cord syndrome.[6]

Clinical Significance

With sudden blockage of blood supply, the common symptoms are sudden back pain that can quickly lead to numbness/weakness or pain that radiates along the nerves branching from the affected area.

Symptomatic treatment and physical therapy are recommended unless a clot or stenosis is identified, in which case surgery is recommended.

There are three major syndromes due to blockage of the spinal arteries.

- Acute central cord syndrome is the most common type of spinal cord injury. Its predominant etiology is cervical spine hyperextension trauma (often seen in MVA) that compresses the spinal cord. It mainly results in symptoms identical to cervical radiculopathy with the added effects of bladder dysfunction and severe paralysis in extreme cases; further confirmation is obtainable through a spurlings test, MRI, or CT scan note such diagnoses should be made urgently to figure out the significance of the blockage.[7]

- Anterior spinal syndrome, in brief, is the most common clinical presentation of a spinal cord infarction. Consistent with its functional neuroanatomy, an anterior infarct/blockage typically presents as loss of motor function and hypotension with relative sparing of proprioception and vibratory sense below the lesion level.

- Posterior cord syndrome will affect the dorsal columns as that is supplied normally by the posterior spinal cords. The patient will most often experience ipsilateral loss of vibration and conscious proprioception; in severe cases, complete loss of sensation is found in the dermatomes corresponding with the levels underneath the level affected even when they are not directly related to the infarction.

Venous infarctions are rare but rapidly progress with near-certain fatality within 36 hours.[8]

Other Issues

Infarcts in the spinal arteries often lead to an irreversible motor/sensory loss; however, new treatments have found that improving oxygen exposure/blood flow over extended periods to damaged areas may improve previous injuries that were at one time thought to be irreversible.[9]

Media

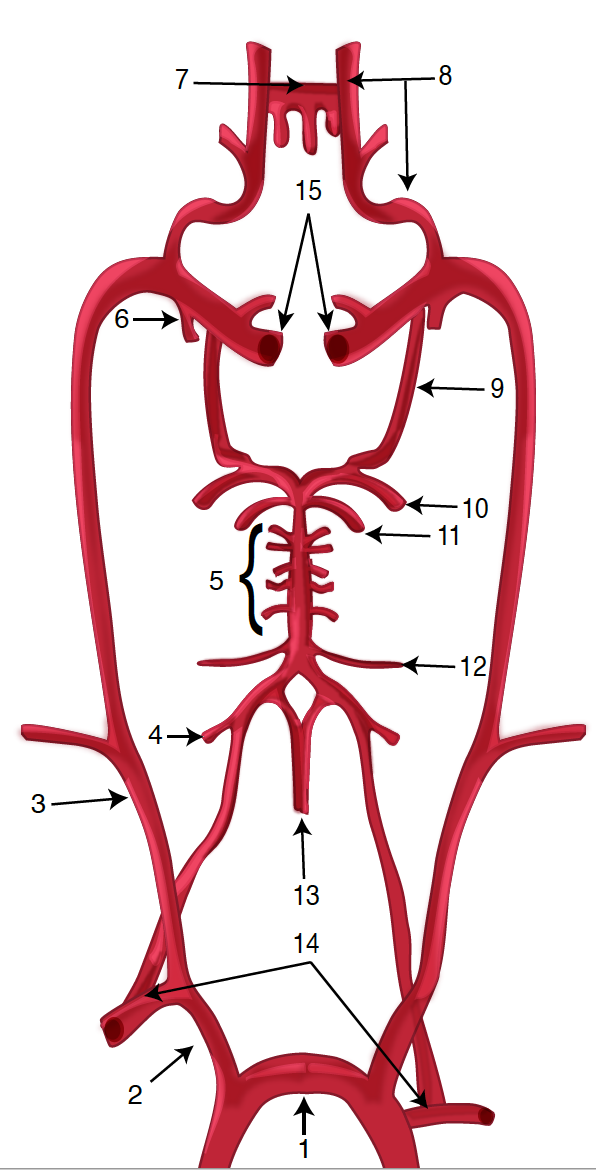

(Click Image to Enlarge)

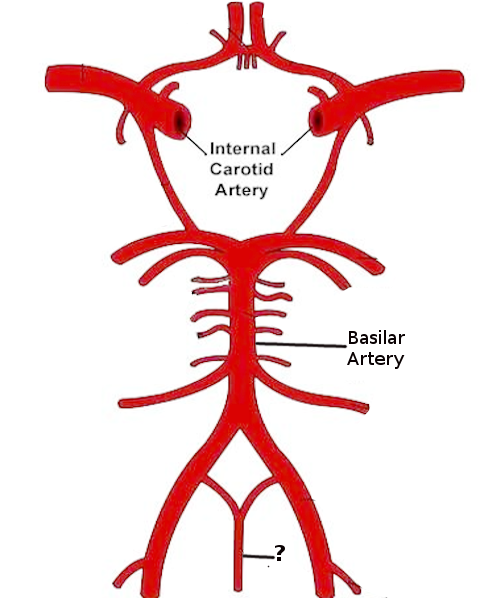

Diagram of the Brain Blood Circulation. Each number corresponds to the following neuroanatomy: 1) aortic arch; 2) brachiocephalic artery; 3) common carotid artery; 4) posterior inferior cerebellar artery; 5) pontine arteries; 6) anterior choroidal artery; 7) anterior communicating artery; 8) anterior cerebral artery; 9) posterior communicating artery; 10) posterior cerebral artery; 11) superior cerebellar artery; 12) anterior inferior cerebellar artery; 13) anterior spinal artery; 14) arches of vertebral arteries; and 15) internal carotid arteries.

Contributed by O Kuybu, MD

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Hasan S, Arain A. Neuroanatomy, Spinal Cord Arteries. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30969711]

Ali F, Reddy V, Dublin AB. Anatomy, Back, Anterior Spinal Artery. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30422558]

Källén K, Mastroiacovo P, Castilla EE, Robert E, Källén B. VATER non-random association of congenital malformations: study based on data from four malformation registers. American journal of medical genetics. 2001 Jun 1:101(1):26-32 [PubMed PMID: 11343333]

Moon BJ, Choi KH, Shin DA, Yi S, Kim KN, Yoon DH, Ha Y. Anatomical variations of vertebral artery and C2 isthmus in atlanto-axial fusion: Consecutive surgical 100 cases. Journal of clinical neuroscience : official journal of the Neurosurgical Society of Australasia. 2018 Jul:53():147-152. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2018.04.058. Epub 2018 Apr 30 [PubMed PMID: 29724649]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWang MX, Smith G, Albayram M. Spinal cord watershed infarction: Novel findings on magnetic resonance imaging. Clinical imaging. 2019 May-Jun:55():71-75. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2019.01.023. Epub 2019 Jan 31 [PubMed PMID: 30763904]

Awad H, Ramadan ME, El Sayed HF, Tolpin DA, Tili E, Collard CD. Spinal cord injury after thoracic endovascular aortic aneurysm repair. Canadian journal of anaesthesia = Journal canadien d'anesthesie. 2017 Dec:64(12):1218-1235. doi: 10.1007/s12630-017-0974-1. Epub 2017 Oct 10 [PubMed PMID: 29019146]

Chakravorty BG, Arterial supply of the cervical spinal cord and its relation to the cervical myelopathy in spondylosis. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 1969 Oct; [PubMed PMID: 4980920]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMuradov JM, Ewan EE, Hagg T. Dorsal column sensory axons degenerate due to impaired microvascular perfusion after spinal cord injury in rats. Experimental neurology. 2013 Nov:249():59-73. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2013.08.009. Epub 2013 Aug 23 [PubMed PMID: 23978615]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMartirosyan NL, Feuerstein JS, Theodore N, Cavalcanti DD, Spetzler RF, Preul MC. Blood supply and vascular reactivity of the spinal cord under normal and pathological conditions. Journal of neurosurgery. Spine. 2011 Sep:15(3):238-51. doi: 10.3171/2011.4.SPINE10543. Epub 2011 Jun 10 [PubMed PMID: 21663407]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence