Introduction

Duodenal ulcers are part of a broader disease state categorized as peptic ulcer disease. Peptic ulcer disease refers to the clinical presentation and disease state that occurs when there is a disruption in the mucosal surface at the level of the stomach or first part of the small intestine, the duodenum. Anatomically, both the gastric and duodenal surfaces contain a defense system that includes pre-epithelial, epithelial, and subepithelial elements. Ulceration occurs from damage to the mucosal surface that extends beyond the superficial layer. While most duodenal ulcers present with dyspepsia as the primary associated symptom, the presentation can range in severity levels, including gastrointestinal bleeding, gastric outlet obstruction, perforation, or fistula development. Therefore, the management is highly dependent on the patient's presentation at the time of diagnosis or progression of the disease. The diagnosis of duodenal vs. gastric ulcer merits consideration in patients with dyspepsia/upper abdominal pain symptoms who also report a history of NSAID use or previous Helicobacter pylori diagnosis. Any patient diagnosed with peptic ulcer disease and, most specifically, the duodenal ulcer should undergo testing for H. pylori as this is a common cause.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The two primary causes for duodenal ulcers are a history of recurrent or heavy NSAID use and a diagnosis of H. pylori.[1] The majority of patients carry a secondary diagnosis of H. pylori; however, as infection rates have declined, other previously uncommon etiologies are becoming more prevalent. Other causes of duodenal ulcers include etiologies that, in similar ways to NSAIDs and H. pylori, disrupt the lining of the duodenum. Some of these include Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, malignancy, vascular insufficiency, and history of chemotherapy.

Epidemiology

According to multiple studies that have evaluated the prevalence of duodenal ulcers, they are estimated to occur in about 5 to 15% of the Western population.[2] Previously, the recurrence and prevalence rates were extremely high due to a lack of identification and effective treatment of H. pylori. Most recently, a systematic review of seven studies discovered the rates to be significantly lower. However, the variability was thought to be due to the prevalence of H. pylori in the population studied and the guidelines for diagnosis utilized, including endoscopic guidelines. In areas with a higher incidence of H. pylori, however, the rates were noted to be the highest, which supports the previously established notion that H. pylori infection presents significant comorbidity for the development of duodenal ulcers.[3] The overall decline in rates of diagnosis of duodenal ulcers is also attributable to developing physician and patient awareness regarding the use of NSAIDs and potential complications that can be associated with misuse as well as the slowly declining rates of smoking amongst younger individuals as research has also been found this to be another confounding comorbidity.

Pathophysiology

As noted above, duodenal ulcers are the result of the corrosive action of gastric secretions on the surface epithelium of the small intestine that has undergone prior injury. In duodenal ulcers, there are multiple underlying comorbidities to consider when establishing the diagnosis and underlying cause. H. pylori and NSAID use are the two main underlying etiologies to consider and discussed here. The mechanism by which H. pylori predisposes individuals is unclear. However, the thinking is that H. pylori colonization and persistent inflammation lead to the weakening of the mucosal surface layer causing it to be vulnerable to exposure to gastric acid. A secondary running theory considers the possibility that H. pylori also can increase acid production via inflammatory mechanisms, further exacerbating the initial injury caused by the infection and initial acid-driven injury.[4]

Prostaglandins play a crucial role in developing the protective mucosa in the gastrointestinal tract, including gastric and small intestine mucosa. Their biosynthesis is catalyzed by the enzyme cyclooxygenase (COX), which exists in two isoforms, COX-1 and COX-2. NSAIDs exhibit their therapeutic effect by inhibiting the COX-1 and COX-2 pathways. Recurrent use of NSAIDs causes a significant and persistent decrease in prostaglandins leading to susceptibility to mucosal injury. It is thought to be one of the primary predisposing pathophysiologic factors for the development of duodenal ulcers.[5] Other secondary causes for duodenal ulcers may work through different underlying mechanisms. However, the ultimate result is generally recurrent mucosal injury that predisposes the tissue to ulceration or an elevation in the amount of acid the mucosa is exposed to, which in turn causes tissue damage.

Histopathology

In cases of H. pylori driven duodenal ulcers, biopsy with histopathological studies can assist in the diagnosis. H. pylori, a spiral-shaped bacterium, can be seen in hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. Reports show the sensitivity and specificity of H&E stain to be 69% to 93% and 87% to 90%, respectively.[6] However, specificity can improve 90% to 100% by using special stains such as modified Giemsa stain, Warthin-Starry silver stain, Genta stain, and immunohistochemical (IHC) stain. As Giemsa stain is straightforward to use, inexpensive and provides consistent results, it is preferred in many laboratories.[6]

History and Physical

The presentation of patients with symptoms consistent with dyspepsia or peptic ulcer disease, and most specifically, duodenal ulcers, can vary highly depending on the degree of disease progression and time when a patient seeks treatment. Most patients with peptic ulcer disease, up to 70%, are asymptomatic. Overall, dyspepsia is the most common symptom for patients who do experience symptoms. As noted above, the degree of disease progression before the initial diagnosis can affect the symptoms with which a patient may present. The location of the disease can also be differentiated based on symptoms.[7] The pain associated with duodenal ulcers improves after meals, while the pain associated with gastric ulcers generally intensifies after meals. Other common signs and symptoms include epigastric abdominal pain, bloating, nausea and vomiting, and weight gain due to improved symptoms post meals.

Patients who initially present with ulcer-related complications may present with symptoms suggestive of upper GI bleed, including melena, hematemesis, elevated BUN, and anemia of varying degrees in severity with associated fatigue. Patients who present with more alarming symptoms such as anemia, melena, or hematemesis, which may represent perforation or bleeding, will likely require more invasive forms of evaluation. The patient's history and age should also be considered when considering duodenal ulcers as part of the differential diagnosis, especially when patients present with more non-specific symptoms such as epigastric abdominal pain. Duodenal ulcers may occur in any age group. However, they are most commonly diagnosed in patients aged 20 to 45 and are more common in men than women. Most patients will have a history of presenting symptoms consistent with peptic ulcer disease (PUD) associated with a previous diagnosis of H. pylori and/or heavy NSAID use. Other elements of the history to consider include smoking history, daily aspirin use, and history of GI malignancy. On physical examination, patients may have epigastric abdominal tenderness, and if presenting with complications, they may demonstrate signs of anemia such as pale skin and positive fecal occult blood test.

Evaluation

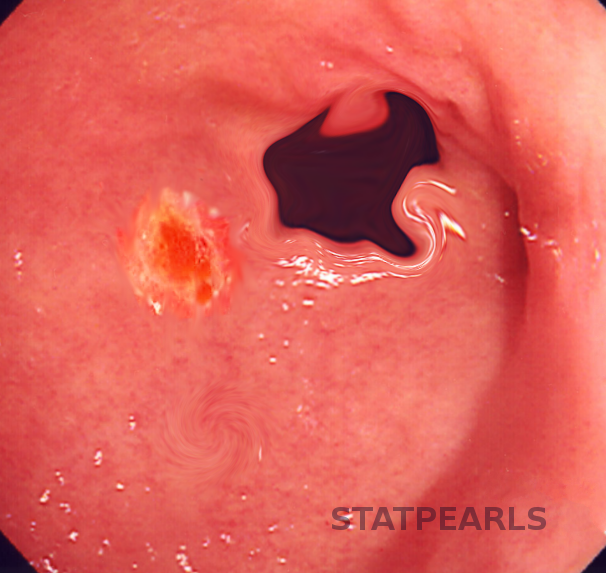

Once the diagnosis of H. pylori based on a history of presenting illness and physical exam findings is a possibility, studies are necessary to establish a definite diagnosis and underlying etiology further. In simple terms, the diagnosis of peptic ulcer disease in general and, more specifically, duodenal ulcers can be made directly by the visualization of the ulcer on upper endoscopy. The evaluation process will depend on what studies the patient may have had completed for the previous assessment of their symptoms. Patients who may have had radiographic imaging completed, which showed evidence of ulceration, but do not have any alarm symptoms suspicious for ulceration/perforation or obstructive pattern, may be treated without the need of endoscopy for visualization of ulcers.

Computed tomography performed for the evaluation of abdominal pain can identify non-perforated peptic ulcers. However, the majority of patients will need a referral for esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) for further evaluation. Duodenal ulcers occur most frequently in the first portion of the duodenum (over 95%), with approximately 90% located within 3 cm of the pylorus and are usually less than or equal to 1 cm in diameter. Barium endoscopy is an option for patients with contraindications to EGD. Once the diagnosis of peptic ulcer disease has been made, it is vital to establish the etiology of the disease as this will help develop a treatment plan for the patient, not only acutely but also a long-term plan to help prevent a recurrence.

Given the high correlation of H. pylori coinfection in the setting of duodenal ulcers, individuals evaluated for H. pylori will need further testing for a formal diagnosis.[8] Biopsy of the tissue during EGD can assist with diagnosis. However, other non-invasive tests may be completed to rule out H. pylori as part of the cause. If the patient has undergone EGD, biopsies can be obtained and further tested with a urease test and histology. Less invasive options include a urea breath test, stool antigen test, and serological tests. Serology is less common, as this can remain positive if the patient has been previously infected and does not necessarily represent active infection. The urea breath test has high specificity. However, false-negative results can occur in the setting of proton pump inhibitor (PPI) use. Stool antigen testing can be used to establish a diagnosis and prove eradication, as it represents ongoing infection.

Treatment / Management

The treatment plan of duodenal ulcers is developed initially based on the degree of disease noted at the time of diagnosis. Patients who present with complications, including perforation or bleeding, may require surgical intervention. However, the majority of patients are treated with antisecretory agents to help reduce the amount of acid exposure to the ulcerated region and, in turn, provide symptomatic relief and promote healing. For patients who present with a history of heavy NSAID use, the first step is to advise patients to avoid NSAID use as this is not only a possible etiology but also a cause of worsening symptoms. Smoking and alcohol cessation is also encouraged, as these may also exacerbate symptoms.

Antisecretory agents include H2 receptor antagonists as well as proton pump inhibitors. The duration of therapy varies highly depending on the presenting symptoms, level of compliance suspected, as well as the risk of recurrence. The majority of patients, however, do not require long-term antisecretory therapy following H. pylori treatment, upon confirmation of eradication and if they remain asymptomatic. Patients diagnosed with H. pylori must receive triple therapy (two antibiotics and a proton pump inhibitors), and elimination must be confirmed.[9] A meta-analysis of 24 randomized trials helped show that eradication of H. pylori was associated with significantly lower rates of both gastric and duodenal ulcers. Patients with complications at the time of presentation will need to follow postoperative recommendations made by their general surgeon. They will likely require treatment for more extended periods (8 to 12 weeks) or until confirmed ulcer resolution by repeat endoscopy. From a surgical standpoint, patients may require laparoscopic repair for perforated ulcers or bleeding ulcers that are not responsive to endoscopic intervention.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis initially established by the evaluating provider will likely vary based on the initial clinical presentation. Patients who present with epigastric abdominal pain symptoms with or without associated variation based on meals may be thought to have gastritis, pancreatitis, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), cholecystitis, or cholelithiasis, biliary colic, and may even be evaluated for possible cardiac etiology with atypical presentation.[10] Patients who present with different symptoms such as hematemesis or melena may have entities such as esophagitis, vascular lesion, or malignancy added to the differentials noted above.

Prognosis

The prognosis of duodenal ulcers is variable depending on the severity of the initial presentation. Duodenal ulcers primarily caused by NSAID use are addressable through discontinuation of the drug and therapy for symptoms with high rates of resolution. Individuals who have developed ulcers due to H. pylori infection will require treatment of the infection, and rates of resolution will vary based on the eradication of infection. Patients who present with severe ulceration or perforation will have higher mortality rates and will be at risk for complications associated with surgical intervention.

Complications

The three main complications associated with duodenal ulcers are bleeding, perforation, and obstruction. For patients who present with bleeding, the majority are manageable via endoscopic intervention. However, a minority of patients will require surgical intervention. Patients who require surgical intervention fail endoscopic intervention, ones with large ulcers or hemodynamically unstable patients despite adequate resuscitation.[11] A small percentage of patients, 2% to 10% of them with peptic ulcer disease, will present with perforation. These patients generally present with very severe diffuse abdominal pain that may start as epigastric pain and become generalized.[12] Surgical intervention merits consideration in patients with perforated ulcers. However, a small percentage of those affected may experience spontaneous sealing of the perforation. Gastric outlet obstruction is the least common complication associated with duodenal ulcers, and studies regarding management and diagnosis are limited.

Consultations

Gastroenterology consultation is often necessary for the diagnosis of duodenal ulcers.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Education for patients treated for ulcers should include the primary causes associated with ulcers, practices to avoid such as NSAID use, and the risk of interventions offered. Individuals should also be advised regarding long-term use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) if this is the therapy of choice for symptomatic management.

Pearls and Other Issues

In younger patients who have duodenal ulcers that are distal to the duodenal bulb, always check a fasting gastrin level to evaluate for a hyper-gastrin state, such as gastrinoma. In older patients with the same finding, consider CT angiography, especially of the celiac trunk and superior mesenteric artery, to assess chronic ischemia.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Early detection and intervention for patients diagnosed with duodenal ulcers are vital for the prevention of complications. The first intervening physician must obtain a thorough history, including details regarding a patient's symptoms and medication use history. For patients who present with more advanced disease, an interprofessional approach to diagnosis and management is critical as surgeons, nurses with specialty gastroenterology training, GI specialists, internal medicine providers, and pharmacists will be involved in providing care and adequate follow-up in a multi-professional healthcare team setting. [Level 5] The diagnostic burden will fall to clinicians (MDs, DOs, mid-level practitioners), including gastroenterology specialists. Nurses can offer counsel on disease management and verify therapy regimen compliance; they are often the first contact point for patients and may be the first to observe therapeutic failure or adverse events. Pharmacists will always perform medication reconciliation, dose, and frequency verification and report back to the prescriber or nursing with any concerns. Pharmacists can also offer medication administration counsel to the patient, reinforcing what the prescriber and nursing have already told them. All these activities need to occur collaboratively. Everyone on the healthcare team has access to the same information level and can contribute from their expertise to positive outcomes.

Media

References

Marshall BJ, Warren JR. Unidentified curved bacilli in the stomach of patients with gastritis and peptic ulceration. Lancet (London, England). 1984 Jun 16:1(8390):1311-5 [PubMed PMID: 6145023]

Cave DR. Transmission and epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori. The American journal of medicine. 1996 May 20:100(5A):12S-17S; discussion 17S-18S [PubMed PMID: 8644777]

Pounder RE, Ng D. The prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in different countries. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics. 1995:9 Suppl 2():33-9 [PubMed PMID: 8547526]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceCrabtree JE. Gastric mucosal inflammatory responses to Helicobacter pylori. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics. 1996 Apr:10 Suppl 1():29-37 [PubMed PMID: 8730257]

Peskar BM. Role of cyclooxygenase isoforms in gastric mucosal defence. Journal of physiology, Paris. 2001 Jan-Dec:95(1-6):3-9 [PubMed PMID: 11595412]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLee JY, Kim N. Diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori by invasive test: histology. Annals of translational medicine. 2015 Jan:3(1):10. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2014.11.03. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25705642]

Wilcox CM, Clark WS. Features associated with painless peptic ulcer bleeding. The American journal of gastroenterology. 1997 Aug:92(8):1289-92 [PubMed PMID: 9260791]

Chey WD, Wong BC, Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. American College of Gastroenterology guideline on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2007 Aug:102(8):1808-25 [PubMed PMID: 17608775]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceChey WD, Leontiadis GI, Howden CW, Moss SF. ACG Clinical Guideline: Treatment of Helicobacter pylori Infection. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2017 Feb:112(2):212-239. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.563. Epub 2017 Jan 10 [PubMed PMID: 28071659]

Meran JG, Wagner S, Hotz J, Manns M. [Differential diagnosis of peptic ulcer]. Wiener medizinische Wochenschrift (1946). 1992:142(8-9):154-61 [PubMed PMID: 1509765]

Lau JY, Sung JJ, Lam YH, Chan AC, Ng EK, Lee DW, Chan FK, Suen RC, Chung SC. Endoscopic retreatment compared with surgery in patients with recurrent bleeding after initial endoscopic control of bleeding ulcers. The New England journal of medicine. 1999 Mar 11:340(10):751-6 [PubMed PMID: 10072409]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBehrman SW. Management of complicated peptic ulcer disease. Archives of surgery (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 2005 Feb:140(2):201-8 [PubMed PMID: 15724004]