Introduction

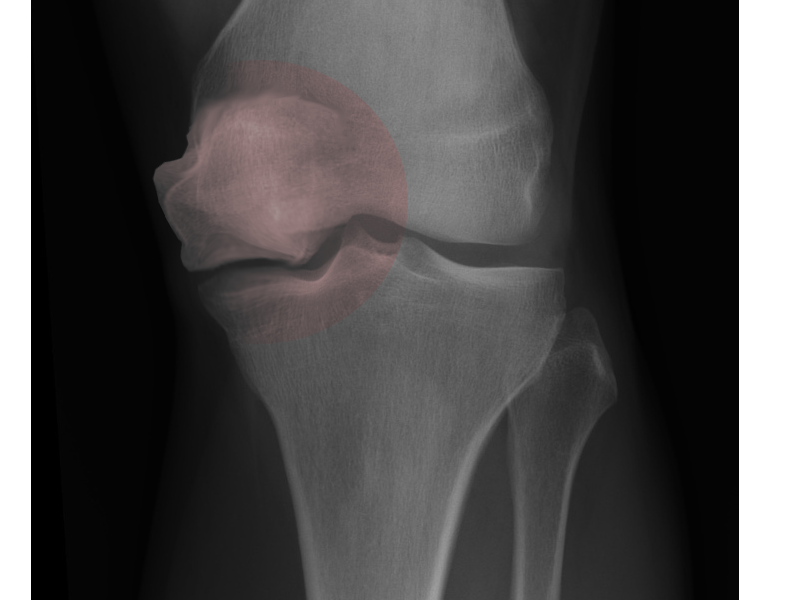

Spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee is a debilitating condition characterized by the sudden onset of knee pain and functional impairment, primarily affecting the medial subchondral bone of the femoral condyles (see Image. Osteonecrosis of the Knee). Ahlbäck first described the condition in 1968, highlighting its hallmark features of a nontraumatic origin and rapid progression.[1] Unlike secondary or post-arthroscopic osteonecrosis, no definitive consensus exists concerning the condition's etiology.[2] However, if left untreated, it can progress to subchondral collapse and secondary osteoarthritis, thereby necessitating surgical intervention.[3][4]

Given the nonspecific and insidious onset, diagnosing and treating spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee can be challenging. Understanding the anatomy of the knee joint is crucial, as the disease mainly impacts the medial femoral condyle, which bears significant weight-bearing stress and may contribute to its development. In contrast, the involvement of the lateral femoral condyle and the tibial plateau is less common.[5]

The natural history of spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee typically follows a pattern of sudden symptom onset without a preceding injury, followed by rapid joint deterioration.[4] Distinctive crescent-shaped osteonecrosis lesions also characterize this condition, and the progression is influenced by various factors, including the size and location of the lesion and the patient's overall health status. The speed and pattern of spread vary, with some patients experiencing a slow progression while others face rapid joint destruction.[6] Some instances of spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee are self-limiting, with symptoms resolving spontaneously over time.[4] However, in many patients, the disease progresses, often resulting in sudden, intense knee pain, swelling, functional impairment, and the risk of joint deterioration. Early stages are marked by severe pain and swelling, progressing to joint space narrowing and osteoarthritic changes. In advanced cases, the necrotic bone may collapse, leading to severe osteoarthritis requiring joint replacement surgery.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The exact etiology of spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee remains unclear due to the condition's complex and multifactorial nature. This presents a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge due to its nonspecific symptoms and gradual onset. Various theories have been proposed, each contributing to our understanding of its pathogenesis.[6] The condition predominantly affects older individuals, hinting at a degenerative component. Key hypotheses for its development include subchondral insufficiency fractures in osteoporotic bones, venous congestion, and localized trauma.[7]

Spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee can be distinguished from secondary osteonecrosis by its insidious onset and lack of identifiable cause.[8] Unlike other types of osteonecrosis, spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee is not commonly associated with systemic risk factors such as corticosteroid use or alcohol abuse, which suggests a more localized disease mechanism. Earlier theories suggested vascular impairment as the primary cause of the condition, leading to bone necrosis.[9] However, histopathologic analysis and similarities to subchondral insufficiency fractures of the femoral head have prompted the proposal that the primary etiology of spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee is a subchondral insufficiency fracture, resulting in localized osteonecrosis.[10][11] These subchondral bone microfractures are believed to initiate a cascade of events, including bone marrow edema, increased intraosseous pressure, and compromised vascular supply, ultimately leading to subchondral plate collapse and subsequent bone necrosis.[12] Additionally, biomechanical factors such as altered load distribution and joint alignment exacerbate subchondral bone stress, particularly in individuals with preexisting joint line abnormalities or those involved in activities that increase knee stress.[9][13]

In 2019, a systematic review by Hussain et al examined the proposed etiologies of spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee and found a strong association between meniscal tears and the condition. The results included meniscal tears occurring in 50% to 100% of spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee patients, with the extent of medial meniscus extrusion correlating with the stage and volume of spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee lesions.[7] This led to the hypothesis that disruption of the posterior medial meniscus root increases tibiofemoral contact pressures, altering knee biomechanics and leading to the subchondral insufficiency fractures characteristic of spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee.[13] Further evidence is needed to pinpoint the exact pathogenesis of the disease, as it remains a source of controversy.

Epidemiology

Spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee predominantly affects middle-aged and older individuals, showing a particular tendency for females aged 60 or older, suggesting a potential association with postmenopausal osteoporosis.[5][14] The exact incidence of spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee is challenging to determine, as it accounts for a relatively small proportion of knee pathologies. Considering that many patients presenting with end-stage osteoarthritis could have previously experienced unrecognized spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee, this prevalence is likely higher than reported.[2][13] Despite its seemingly limited occurrence, the significant impact of spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee on individuals highlights the need for more focused attention and research.

Epidemiological studies reveal a higher occurrence of spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee in Western populations, a discrepancy that could be due to variations in lifestyle, healthcare accessibility, and diagnostic practices. The notable prevalence among older adults, particularly postmenopausal women aged 60 or older, reinforces the proposed role of age-related bone density loss and osteoporosis in the development of spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee.[4][5] This correlation extends to associations with medial meniscus posterior root tears, suggesting a complex interplay of risk factors, including age, gender, bone health, and possibly genetic predisposition.[13][15]

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee is characterized by a sequence of events leading to the death of subchondral bone tissue.[5] The initial event is often a microfracture in the subchondral bone, particularly in individuals with osteoporosis or reduced bone mineral density. This microfracture compromises the structural integrity of the bone, making it susceptible to further damage under normal mechanical loads.[16] Increased intraosseous pressure secondary to associated bone marrow edema further exacerbates the ischemic process. This elevated pressure impairs venous outflow and arterial inflow, leading to a hypoxic environment.[17] Inflammatory cytokines and biomechanical stress responses also contribute to this progression, exacerbating the joint degeneration seen in advanced cases.[18]

History and Physical

Patients with spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee typically present with acute-onset, unilateral knee pain, which is disproportionate to any inciting event.[17] The pain is localized, often on the medial side, and exacerbated by weight-bearing activities. Patients can sometimes recall precisely when the symptoms began and may report a history of mild trauma or no trauma at all, making the diagnosis challenging.[11][19] In some cases, patients may present with a more insidious onset of symptoms, with a gradual worsening of pain and swelling. This presentation can mimic other degenerative joint diseases, necessitating a thorough examination and differential diagnosis.

Physical examination reveals tenderness at the joint line, particularly over the medial femoral condyle. There is often a mild effusion and reduced range of motion due to pain.[8] Crepitus may also be present, indicating underlying articular surface damage. Assessing the knee's alignment and stability is crucial, as varus or valgus deformities can influence the disease course.[20]

Evaluation

The diagnosis of spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee is primarily based on clinical presentation and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings, focusing on excluding other potential causes of knee pain.[8] The initial evaluation should include plain radiographs of the knee, which show subchondral sclerosis, collapse, joint space narrowing, and flattening of the involved condyles in the later stages of the disease. Early in the disease course, however, x-rays are often normal.[21]

MRI is the gold standard for diagnosing spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee, given its high sensitivity to bone edema.[14] Key MRI findings include bone marrow edema, subchondral crescent fracture lines, and focal areas of necrosis with epiphyseal contour depression. T1-weighted images generally reveal a serpentine low-signal area representing necrotic bone surrounded by edematous bone marrow, while T2-weighted images more clearly highlight the edema. A subchondral crescent or linear focus of low signal intensity may be observed in both T1 and potentially T2 sequences.[22]

MRI's high sensitivity is instrumental in evaluating the extent of the disease, which is crucial for devising treatment strategies. MRI enables precise measurements of the lesion's width, depth, and height in both coronal and sagittal sections, and offers accurate assessments of meniscal tears and the degree of meniscal extrusion, which are pivotal in understanding spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee's pathophysiology. Although bone scintigraphy is less frequently used due to its lower sensitivity and specificity compared to MRI, it may reveal increased uptake in the affected area.[14]

In addition to imaging, laboratory tests may be conducted to rule out other causes of knee pain, such as infection or inflammatory arthritis. These tests include a complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein levels.[23]

Treatment / Management

Treatment and Management of Spontaneous Osteonecrosis of the Knee

The management of spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee is personalized depending on disease severity, symptomatology, and patient health status. The decision to treat spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee is largely based on lesion size and stage. Small lesions may regress with non-surgical management, while larger lesions often necessitate surgical intervention. In the pre-collapse state, joint-preserving procedures should be attempted. If post-collapse has occurred, total joint arthroplasty is a viable option. Treatment ranges from nonoperative approaches in early, less severe cases to operative interventions when conservative measures fail or the disease progresses.[14][24]

Nonoperative modalities: Nonoperative treatment is advisable for small lesions less than 3.5 cm2, which often regress without surgery.[23][25] This includes the below-mentioned management strategies.(B2)

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and analgesics: They are first-line options for pain, with NSAIDs working to mitigate inflammation and narcotics being used for severe discomfort.

- Protected weight bearing: This involves minimizing stress on the knee through the utilization of canes or crutches to prevent further damage.

- Physical therapy: This entails exercises aimed at enhancing knee mobility and muscle strength to reduce joint stress.

- Bisphosphonates: These may delay surgery by preventing subchondral collapse, though their effectiveness requires further study. These medications may delay surgery by preventing subchondral collapse, although additional research is needed to ascertain their effectiveness. Their mechanism of action, which involves inhibiting bone resorption, might stabilize the disease process.

A conservative approach can resolve symptoms in many patients with pre-collapse spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee and normal radiographs. However, surgical options may be considered if there is no improvement after 3 months.

Operative and surgical interventions: For lesions larger than 3.5 cm2 or in post-collapse stages, surgical management may be necessary, which includes the below-mentioned management strategies.

- Arthroscopy: This technique assesses the lesion and addresses any concurrent meniscal or chondral issues.

- Core decompression: This procedure alleviates symptoms by reducing intraosseous pressure and encouraging new blood vessel formation.

- Osteochondral grafting: This technique involves transplanting native cartilage (autograft) or allograft cartilage to restore joint integrity.

Joint-preserving techniques, such as arthroscopic debridement and microfracture repair, can postpone the need for arthroplasty. Duany et al reported an 87% success rate in preserving the native knee joint using such surgical techniques in patients with pre-collapse spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee at a mean follow-up of 40 months.[26]

Advanced stages:

- High tibial osteotomies: They are recommended for younger, active patients with malalignment, aiming to offload the affected condyle and promote healing.

- Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA): This procedure is suitable for single-compartment disease. It is typically the preferred option over total knee arthroplasty (TKA) as it allows for preserving bone stock and knee kinematics. Outcomes for UKA are similar when performed for spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee or osteoarthritis.

- TKA: This procedure is indicated for extensive multi-compartmental disease or inflammatory arthropathy.

Each surgical procedure carries specific risks and potential complications. Ultimately, the management strategy for spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee should be a coordinated effort among a patient and a multidisciplinary healthcare team, ensuring that the chosen approach aligns with the patient's lifestyle and expectations, aiming for pain relief, functional improvement, and quality of life.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee includes a variety of conditions that can present with similar clinical and imaging features.[4] Degenerative arthritis is the most common differential diagnosis, especially in older patients. Inflammatory conditions like rheumatoid arthritis must be ruled out through laboratory testing and clinical evaluation.

Other types of osteonecrosis, such as those associated with steroid use or alcoholism, have different clinical and radiological features compared to spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee and often involve a more extensive area of the knee.[2] Accurately distinguishing spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee from the below-mentioned conditions is crucial for effective management.

- Osteoarthritis: Common in older patients, presenting with a gradual onset of symptoms and often bilateral. Unlike spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee, osteoarthritis involves a more progressive course of joint degradation.

- Meniscal tear: Mimics spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee symptomatically but is usually linked to a history of trauma or twisting injury, often confirmed by a positive McMurray test.

- Septic arthritis: Considered especially with joint effusion, inability to bear weight or range the knee, and systemic symptoms; requires immediate attention to prevent joint damage.

- Inflammatory arthritis: Certain conditions, such as rheumatoid arthritis, show systemic features and multiple joint involvements, distinguishable through laboratory tests and clinical evaluation.

- Osteochondritis dissecans: Typically seen in younger patients, characterized by localized bone and cartilage necrosis.

- Transient osteoporosis: Presents with rapid-onset joint pain and bone marrow edema but without necrosis and primarily affects the hip.

- Shifting bone marrow edema syndrome: Characterized by migratory bone marrow edema, often affecting multiple joints over time.

- Bony contusion or occult fracture: May present similarly but usually follows a history of significant trauma.

- Secondary osteonecrosis: Unlike spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee, it often involves both femoral condyles and extends to the epiphysis, metaphysis, and diaphysis. This condition is usually bilateral, with a strong association with risk factors such as corticosteroid use, alcoholism, sickle cell disease, and Gaucher disease.

- Post-arthroscopic necrosis: Occurs following knee arthroscopy, characterized by localized necrosis, and often associated with preexisting knee pathologies and differentiated from spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee by its apparent link to surgical intervention.

Prognosis

The prognosis of spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee varies depending on the size of the lesion, with more extensive lesions portending an increased risk of disease progression and subsequent need for surgical management.[27] Early-stage spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee can have a favorable outcome with the resolution of symptoms and preservation of joint function, especially when managed conservatively.[26] However, if left untreated or in advanced stages, spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee can lead to joint collapse and significant functional impairment.

The prognosis also depends on factors such as patient age, comorbidities, and overall health status. Younger patients with fewer comorbidities generally have a better prognosis, as they are more likely to respond positively to conservative treatments and recover more effectively from surgical interventions. Jureus et al reported there was an extremely high likelihood of progression to osteoarthritis when 40% or more of the joint surface was affected by spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee for patients with a mean follow-up of 15 years.[3] The success of surgical interventions, such as TKA, in advanced spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee is favorable, with most patients achieving pain relief and improved joint function. However, the prognosis is less favorable in younger patients or those with active lifestyles, as joint replacement may limit certain activities.[19]

The prognosis of spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee is also closely tied to the stage of the disease at diagnosis, with classifications like the Koshino classification providing a framework for understanding disease progression and associated outcomes. The Koshino classification helps clinicians estimate the disease's progression and guide treatment decisions.[14] Early stages (1 and 2) have a more favorable prognosis with conservative management, focusing on symptom relief and preventing further joint damage. In contrast, stages 3 and 4 often require more aggressive interventions due to the higher risk of joint collapse and severe osteoarthritis.[5]

The Koshino Classification

The Koshino Classification provides a staging system for spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee, outlining different disease manifestations and prognostic implications, as mentioned below.

- Stage 1: Characterized by normal radiographs but MRI showing bone marrow edema. The prognosis in this stage is generally favorable with conservative management, as the bone marrow edema may resolve without progression to bone necrosis.

- Stage 2: Radiographs show a sclerotic area in the subchondral region, indicating early bone changes. In this stage, conservative treatment can still be effective, but there is a higher risk of disease progression compared to Stage 1.

- Stage 3: Defined by a crescent sign on radiographs, indicative of subchondral collapse. The prognosis becomes guarded at this stage, as the structural integrity of the bone is compromised, increasing the risk of joint degeneration and arthritis.

- Stage 4: Advanced joint destruction and osteoarthritic changes are visible on radiographs. The prognosis at this stage is poor for joint preservation, and surgical intervention, such as TKA, is often necessary.

Complications

Spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee is a progressive disease, and the patient’s condition will continue to deteriorate if not diagnosed and treated promptly.[28] The complications of spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee mainly arise from disease progression and the risks inherent in surgical interventions. In the long term, patients with spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee may face challenges in maintaining an active lifestyle, and there is an increased risk of developing osteoarthritis in the affected knee. Progressive joint degeneration can lead to chronic pain, decreased mobility, and a reduced quality of life. Surgical complications include infection, thromboembolism, and implant failure. Arthroscopic procedures carry risks of joint stiffness and persistent pain.[29]

Complications of Spontaneous Osteonecrosis of the Knee

- Progression to osteoarthritis: One of the most common complications of spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee is the progression to osteoarthritis in the affected knee. This can lead to joint stiffness, decreased range of motion, and chronic pain.

- Joint collapse: In advanced stages, spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee can lead to subchondral collapse, which significantly worsens symptoms and limits functional ability.

- Increased risk of fractures: The weakened bone structure in the affected area can increase the risk of insufficiency fractures.

- Impaired mobility: As the condition progresses, patients may experience significant limitations in mobility, affecting their quality of life.

- Chronic pain: Persistent pain, even after treatment, is a common complication that can be challenging to manage.

Arthroscopic Surgery and Core Decompression

- Limited efficacy: These procedures may not always provide lasting relief, especially in the advanced stages of spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee.

- Risk of infections: As with any surgical procedure, there is a risk of infection at the incision or inside the joint.

- Blood clots: Similar to TKA/UKA, there is a risk of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism.

- Worsening symptoms: In some cases, symptoms may worsen after surgery, particularly if the procedure does not adequately address the underlying pathology.

- Scarring and stiffness: Arthroscopic surgery can lead to scarring within the joint, which may result in stiffness and limited range of motion.

Complications Specific to Surgical Interventions—TKA and UKA

- Infections: The risk of infection is low but remains a significant concern with knee replacement surgeries.

- Blood clots: Following these procedures, there is an increased risk of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism.

- Implant loosening or failure: Over time, the implants used in TKA or UKA can loosen or fail, requiring revision surgery.

- Periprosthetic fractures: Fractures around the implant site can occur, especially in patients with osteoporosis or weakened bone structure.

- Nerve and vascular injury: Severe but rare complications include damage to the nerves or blood vessels around the knee.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Deterrence of spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee involves educating patients about risk factors and early symptoms to promote timely medical intervention.[11] Key to this is raising awareness about the condition, particularly in high-risk groups such as older patients and postmenopausal women. Patients should be informed about the importance of maintaining good bone health through adequate calcium and vitamin D intake, regular weight-bearing exercises, and avoiding smoking and excessive alcohol consumption, all of which can reduce the risk of osteoporosis and spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee.[23][25]

Patient education should also focus on recognizing early signs of spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee, like sudden knee pain without a history of trauma, especially in older adults. This knowledge can prompt early medical consultation, leading to quicker diagnosis and management and potentially mitigating the progression of the disease. Additionally, educating patients about the potential benefits and risks of different treatment modalities, including conservative and surgical options, empowers them to make informed decisions about their care.[14] For those diagnosed with spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee, guidance on activity modification is crucial. Patients should avoid activities that exacerbate knee pain while engaging in gentle exercises to maintain joint mobility and muscle strength. Weight management strategies are also essential to reduce stress on the knee joints.[30]

Pearls and Other Issues

Historical Anecdotes

Origin: The term "osteonecrosis" was first used in the early 20th century, but the specific understanding of spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee evolved much later. The condition is named after Dr Ahlbäck (Ahlbäck disease), who was one of the first to describe it in 1968 and brought attention to its unique presentation in the knee. Despite its name, the "spontaneous" nature of spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee is somewhat misleading. Emerging evidence suggests that microtraumas, often unnoticed by patients, may play a significant role in its pathogenesis.

Evolution of understanding: Historically, spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee was often misdiagnosed as arthritis due to similar symptoms. Advancements in imaging techniques, especially MRI, have greatly improved the accuracy of diagnosis, distinguishing it from other joint pathologies. There is ongoing research into the potential genetic predisposition for spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee, which could open avenues for preventive strategies in the future.

Clinical Pearls

Age and gender specificity: Spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee most commonly affects women aged 60 or older. This demographic focus provides a crucial diagnostic clue when an older patient presents with acute knee pain.

Rapid onset: Unlike degenerative joint diseases, which develop gradually, spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee typically presents with a sudden onset of pain in the absence of trauma. This rapid onset should raise suspicion for spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee in the appropriate demographic.

Importance of early intervention: Early diagnosis and management can significantly alter the disease's progression. Delayed treatment can lead to joint collapse and the need for more invasive procedures such as TKA.

Diagnostic Pitfalls

Misinterpreting imaging: MRI findings in the early stages of spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee can be subtle, leading to underdiagnosis. To avoid misinterpretation, radiologists and clinicians must recognize early signs of the condition, such as bone marrow edema.

Differentiating from meniscal tears: Spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee can mimic symptoms of meniscal tears or other ligamentous injuries. However, unlike meniscal tears, spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee shows specific changes in the subchondral bone.

Management Pearls

Conservative management: In the early stages, conservative management, including rest, analgesia, and possibly bracing, can be effective. This approach is often preferred in older patients where surgery poses higher risks.

Surgical decisions: For advanced cases, surgical options like core decompression or osteotomy can be considered, but the decision should be based on a comprehensive evaluation of the patient's overall health, activity level, and the disease's extent.

Patient Education

Activity modification: Educating patients about activity modification and weight management is crucial. Reducing the load on the affected knee can slow the progression and alleviate symptoms.

Osteoporosis management: Given the association with osteoporosis, patients should be counseled on bone health, including diet, exercise, and medication to improve bone density.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Effective management of spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee requires a highly coordinated effort from an interprofessional healthcare team, comprising physicians, nurses, radiologists, physical therapists, and, when necessary, orthopedic surgeons. Physicians and advanced practice providers are critical in conducting the initial assessment, diagnosing spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee, and formulating a comprehensive treatment plan. Radiologists contribute significantly by interpreting imaging studies crucial for diagnosis, while nurses are instrumental in patient education, ensuring adherence to treatment plans, and providing ongoing support. Physical therapists develop personalized rehabilitation programs to maintain joint function and muscle strength. In cases requiring surgical intervention, orthopedic surgeons collaborate closely with the team to select the most suitable procedure and manage preoperative and postoperative protocols. Regular team meetings and a centralized system for documenting patient interactions ensure that all team members stay informed and maintain a unified approach.

Gaining a deeper understanding of the condition's etiology, alongside advancements in diagnostic and therapeutic approaches, is crucial for shedding light on this complex condition. Although relatively rare, spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee demands a high level of vigilance from healthcare providers, especially during the evaluation of patients with knee tenderness.[19] Given that this condition is often initially encountered by primary care providers or in emergency departments, it underscores the importance of being well-versed in spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee. Prompt recognition, accurate diagnosis, and timely referral to specialists are essential for preventing significant disability. An orthopedic-trained nurse or advanced practice provider plays a vital role in managing spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee, aiding in patient compliance with medical therapy, assisting during surgical interventions, and providing patient counseling and post-surgical assessments. The collaborative efforts of these diverse specialties highlight the significance of an interprofessional team approach in achieving optimal outcomes for patients with spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee, regardless of the disease stage.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Ahlbäck S, Bauer GC, Bohne WH. Spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee. Arthritis and rheumatism. 1968 Dec:11(6):705-33 [PubMed PMID: 5700639]

Mont MA, Marker DR, Zywiel MG, Carrino JA. Osteonecrosis of the knee and related conditions. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2011 Aug:19(8):482-94 [PubMed PMID: 21807916]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceJuréus J, Lindstrand A, Geijer M, Robertsson O, Tägil M. The natural course of spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee (SPONK): a 1- to 27-year follow-up of 40 patients. Acta orthopaedica. 2013 Aug:84(4):410-4. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2013.810521. Epub 2013 Jun 25 [PubMed PMID: 23799344]

Mont MA, Baumgarten KM, Rifai A, Bluemke DA, Jones LC, Hungerford DS. Atraumatic osteonecrosis of the knee. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 2000 Sep:82(9):1279-90 [PubMed PMID: 11005519]

Zaremski JL, Vincent KR. Spontaneous Osteonecrosis of the Knee. Current sports medicine reports. 2016 Jul-Aug:15(4):228-9. doi: 10.1249/JSR.0000000000000271. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27399818]

Lotke PA, Ecker ML. Osteonecrosis of the knee. The Orthopedic clinics of North America. 1985 Oct:16(4):797-808 [PubMed PMID: 4058904]

Yasuda T, Ota S, Fujita S, Onishi E, Iwaki K, Yamamoto H. Association between medial meniscus extrusion and spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee. International journal of rheumatic diseases. 2018 Dec:21(12):2104-2111. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.13074. Epub 2017 Apr 5 [PubMed PMID: 28378451]

Ecker ML, Lotke PA. Spontaneous Osteonecrosis of the Knee. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 1994 May:2(3):173-178 [PubMed PMID: 10709006]

Jones JP Jr. Alcoholism, hypercortisonism, fat embolism and osseous avascular necrosis. 1971. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 2001 Dec:(393):4-12 [PubMed PMID: 11764370]

Yamamoto T, Bullough PG. Spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee: the result of subchondral insufficiency fracture. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 2000 Jun:82(6):858-66 [PubMed PMID: 10859106]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceNarváez JA, Narváez J, De Lama E, Sánchez A. Spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee associated with tibial plateau and femoral condyle insufficiency stress fracture. European radiology. 2003 Aug:13(8):1843-8 [PubMed PMID: 12942284]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMalghem J, Lecouvet F, Vande Berg B, Kirchgesner T, Omoumi P. Subchondral insufficiency fractures, subchondral insufficiency fractures with osteonecrosis, and other apparently spontaneous subchondral bone lesions of the knee-pathogenesis and diagnosis at imaging. Insights into imaging. 2023 Oct 2:14(1):164. doi: 10.1186/s13244-023-01495-6. Epub 2023 Oct 2 [PubMed PMID: 37782395]

Hussain ZB, Chahla J, Mandelbaum BR, Gomoll AH, LaPrade RF. The Role of Meniscal Tears in Spontaneous Osteonecrosis of the Knee: A Systematic Review of Suspected Etiology and a Call to Revisit Nomenclature. The American journal of sports medicine. 2019 Feb:47(2):501-507. doi: 10.1177/0363546517743734. Epub 2017 Dec 18 [PubMed PMID: 29253348]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKarim AR, Cherian JJ, Jauregui JJ, Pierce T, Mont MA. Osteonecrosis of the knee: review. Annals of translational medicine. 2015 Jan:3(1):6. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2014.11.13. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25705638]

Akamatsu Y, Mitsugi N, Hayashi T, Kobayashi H, Saito T. Low bone mineral density is associated with the onset of spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee. Acta orthopaedica. 2012 Jun:83(3):249-55. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2012.684139. Epub 2012 Apr 27 [PubMed PMID: 22537352]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMears SC, McCarthy EF, Jones LC, Hungerford DS, Mont MA. Characterization and pathological characteristics of spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee. The Iowa orthopaedic journal. 2009:29():38-42 [PubMed PMID: 19742083]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePareek A, Parkes CW, Bernard C, Camp CL, Saris DBF, Stuart MJ, Krych AJ. Spontaneous Osteonecrosis/Subchondral Insufficiency Fractures of the Knee: High Rates of Conversion to Surgical Treatment and Arthroplasty. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 2020 May 6:102(9):821-829. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.19.00381. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32379123]

Houpt JB, Pritzker KP, Alpert B, Greyson ND, Gross AE. Natural history of spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee (SONK): a review. Seminars in arthritis and rheumatism. 1983 Nov:13(2):212-27 [PubMed PMID: 6369544]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSerrano DV, Saseendar S, Shanmugasundaram S, Bidwai R, Gómez D, D'Ambrosi R. Spontaneous Osteonecrosis of the Knee: State of the Art. Journal of clinical medicine. 2022 Nov 25:11(23):. doi: 10.3390/jcm11236943. Epub 2022 Nov 25 [PubMed PMID: 36498517]

Ochi J, Nozaki T, Nimura A, Yamaguchi T, Kitamura N. Subchondral insufficiency fracture of the knee: review of current concepts and radiological differential diagnoses. Japanese journal of radiology. 2022 May:40(5):443-457. doi: 10.1007/s11604-021-01224-3. Epub 2021 Nov 29 [PubMed PMID: 34843043]

Zimmerman ZE, Bisson LJ, Katz JN. Perspective on subchondral insufficiency fracture of the knee. Osteoarthritis and cartilage open. 2021 Sep:3(3):100183. doi: 10.1016/j.ocarto.2021.100183. Epub 2021 May 19 [PubMed PMID: 36474819]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGil HC, Levine SM, Zoga AC. MRI findings in the subchondral bone marrow: a discussion of conditions including transient osteoporosis, transient bone marrow edema syndrome, SONK, and shifting bone marrow edema of the knee. Seminars in musculoskeletal radiology. 2006 Sep:10(3):177-86 [PubMed PMID: 17195126]

Yates PJ, Calder JD, Stranks GJ, Conn KS, Peppercorn D, Thomas NP. Early MRI diagnosis and non-surgical management of spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee. The Knee. 2007 Mar:14(2):112-6 [PubMed PMID: 17161606]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMyers TG, Cui Q, Kuskowski M, Mihalko WM, Saleh KJ. Outcomes of total and unicompartmental knee arthroplasty for secondary and spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 2006 Nov:88 Suppl 3():76-82 [PubMed PMID: 17079371]

Yang WM, Zhao CQ, Lu ZY, Yang WY, Lin DK, Cao XW. Clinical Characteristics and Treatment of Spontaneous Osteonecrosis of Medial Tibial Plateau: A Retrospective Case Study. Chinese medical journal. 2018 Nov 5:131(21):2544-2550. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.244113. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30381587]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDuany NG, Zywiel MG, McGrath MS, Siddiqui JA, Jones LC, Bonutti PM, Mont MA. Joint-preserving surgical treatment of spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee. Archives of orthopaedic and trauma surgery. 2010 Jan:130(1):11-6. doi: 10.1007/s00402-009-0872-2. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19387670]

Lotke PA, Abend JA, Ecker ML. The treatment of osteonecrosis of the medial femoral condyle. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 1982 Nov-Dec:(171):109-16 [PubMed PMID: 7140057]

Tveit M. The Renaissance of Unicompartmental Knee Arthroplasty appears rational - A radiograph-based comparative Study on adverse Events and patient-reported Outcomes in 353 TKAs and 98 UKAs. PloS one. 2021:16(9):e0257233. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0257233. Epub 2021 Sep 16 [PubMed PMID: 34529691]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWu PJ, Lin TY, Lu YC. A Retrospective Study of Unicompartmental Knee Arthroplasty Functional Outcome and the Incidence of Medial Meniscus Posterior Root Tear in Spontaneous Osteonecrosis of the Knee. BioMed research international. 2021:2021():6614122. doi: 10.1155/2021/6614122. Epub 2021 Apr 30 [PubMed PMID: 33997024]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceZmerly H, Moscato M, Akkawi I, Galletti R, Di Gregori V. Treatment options for secondary osteonecrosis of the knee. Orthopedic reviews. 2022:14(3):33639. doi: 10.52965/001c.33639. Epub 2022 Apr 25 [PubMed PMID: 35775038]