Introduction

Lichen planopilaris is an inflammatory, primary cicatricial alopecia that presents with different hair loss patterns. Similar to lichen planus, the etiology of lichen planopilaris is unknown but is presumably related to the cause of lichen planus.[1][2][3] Lichen planopilaris results in patchy, progressive, permanent hair loss, mainly affecting the scalp while also extending to other hair-bearing regions such as the eyebrows and pubic area.[4] Understanding the nature of autoimmune diseases and the role of inflammatory processes is crucial in guiding treatment decisions.

The epidemiology of lichen planopilaris, a dermatological condition, is also unclear. Recent evidence-based approaches advocate for the use of corticosteroids, topical tacrolimus, antimalarial drugs, and emerging treatments such as JAK inhibitors. In addition, patient education, interdisciplinary collaboration, and long-term management strategies are critical for improving functionality, considering the significant impact on lifestyle and appearance.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Lichen planopilaris is the prototypical lymphocytic cicatricial alopecia, according to the North American Hair Research Society (NAHRS). This condition is considered a follicular variant of lichen planus based on clinical and histopathological findings. The most widely accepted theory states that the condition is a hair-specific autoimmune disorder where activated T-lymphocytes target follicular antigens.[5][6]

The exact etiological cause of lichen planopilaris is unknown. However, signs of alopecia are believed to be a cytotoxic autoimmune response to a yet unknown antigen present in hair follicles. The disease is rarely induced by genetic factors or drugs. However, there may be a correlation with monoclonal antibodies such as pembrolizumab.[7][8] The use of nilotinib is also linked.[9]

Epidemiology

The incidence of any of the cicatricial alopecias is not precisely known. Lichen planopilaris has been reported as the most frequent primary scarring alopecia, accounting for 43% of cases in a series involving 72 patients. Frontal fibrosing alopecia and Graham-Little syndrome are considered variants of lichen planopilaris. The alopecia typically affects women between ages 40 and 60, more often compared to men. Up to 50% of patients may develop characteristic lichen planus lesions that affect the skin, mucous membranes, or nails.[10][11]

Pathophysiology

Cell-mediated immunity plays a significant role in triggering the clinical expression of lichen planopilaris. This cell-mediated reaction is potentially initiated by the action of endogenous or exogenous agents, such as drugs, viruses, or contact sensitizers that bind to keratinocytes as well as follicular epithelium. Contact sensitizers, such as gold, mercury, and cobalt metals, could act as haptens and evoke an inflammatory reaction. Microorganisms that may play a role include the hepatitis C virus, HIV, herpes simplex virus type 2, human papillomavirus, and syphilis. Antimalarial agents, gold, beta-blockers, thiazide diuretics, and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors are involved.

Following this initial trigger, keratinocytes and hair follicles may act as signal transducers, capable of converting these stimuli into cytokines and chemotactic factors to initiate and perpetuate inflammation. Most infiltrated T-lymphocytes are concentrated around the bulge area. Lineage studies have demonstrated that cells within the bulge area are multipotent, and their progeny generates new lower anagen hair follicles. The failure of affected follicles to regenerate is believed to be due to the destruction of follicular stem cells in the bulge area.[12][13][14]

Histopathology

A band-like mononuclear infiltrate obscuring the interface between the follicular epithelium and the dermis is observed in lichen planopilaris. The epithelial-stromal junction may have prominent vacuoles and dyskeratosis with individually necrotic, polygonal basal keratinocytes. Inflammation affects the upper portion of the follicle most severely, but this may extend down the length of the follicle. Perifollicular fibrosis and chronic inflammation are observed in later stages. Ultimately, follicles are replaced by columns of sclerotic collagen called follicular scars. Elastic tissue stains can be used to highlight these scars. Grouped globular immunofluorescence, typically IgM, especially when found adjacent to the follicular epithelium, is the characteristic pattern observed in lichen planopilaris. This pattern is in contrast to chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus, where linear deposits of immunoreactants are typical.[15]

History and Physical

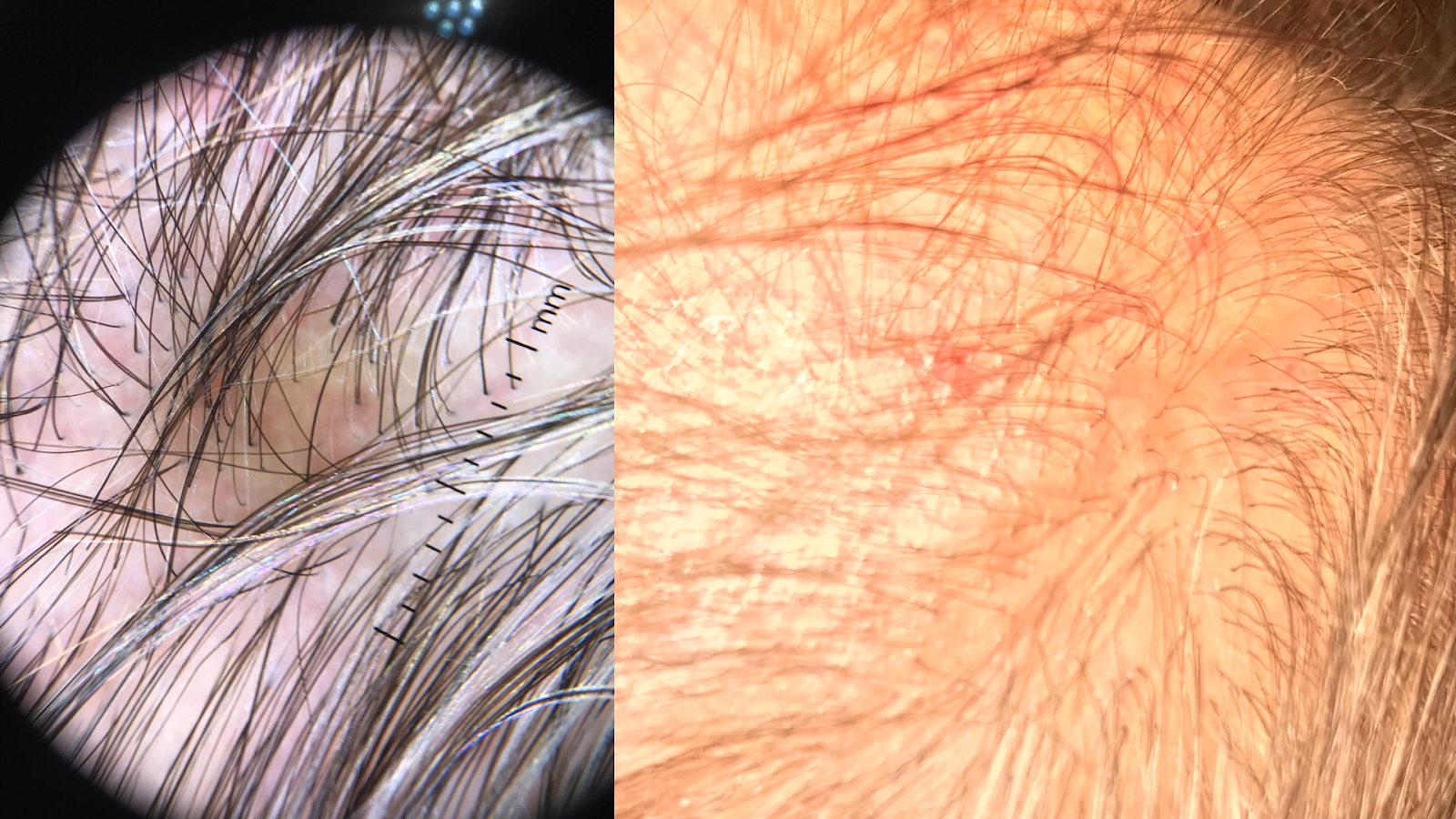

The clinical course of hair loss in lichen planopilaris may be insidious or fulminant, and the pattern is highly variable. Several scattered foci of partial hair loss are commonly associated with perifollicular erythema and scaling. A pattern of hair loss suggestive of central centrifugal alopecia or Brocq alopecia can also occur. The scalp lesions may be single or multiple, focal or diffuse, and occur anywhere on the scalp (see Image. Patient with Lesions of Lichen Planopilaris). Hair follicles around the margins of the bare areas show perifollicular erythema and perifollicular scale, unlike discoid lupus erythematosus, where follicular plugging is in the center of the active bare patch (see Image. Dermoscopic and Clinical Findings in Lichen Planopilaris).

A pull test may yield anagen hairs in cicatricial alopecia, indicating active disease requiring treatment. Symptoms such as itching, burning, pain, and tenderness are often severe. Cutaneous, nail, and mucous membrane lichen planus may occur before, during, or after the onset of scalp involvement. Perifollicular scaling is the most characteristic trichoscopic feature of active lichen planopilaris. Trichoscopy of inactive end-stage lichen planopilaris reveals small, irregularly shaped, whitish areas lacking follicular openings, called fibrotic white dots, and white areas of conducted fibrosis.[16]

Evaluation

The diagnosis is based on the clinicopathologic correlation rather than solely on clinical signs and symptoms. A 4-mm-deep punch biopsy specimen should be submitted for horizontal sectioning and hematoxylin-eosin staining. The best biopsy site is an active, symptomatic hair-bearing area with perifollicular erythema and perifollicular scale located at the margin of a bare patch with a positive anagen pull test.[17]

Treatment / Management

The main objectives of treatment are to reduce hair loss, control the symptoms, and stop the scarring process. Regrowth should not be expected as the complete elimination of inflammation is unlikely. As no consistent markers measure the disorder's progress, therapy is based on perceived severity and patient tolerance to treatment. The duration of treatment should be guided by clinical response and relapse rates. General measures include avoiding chemical or physical insults to the hair, such as coloring or perming. Contrary to many patients' beliefs, the frequency of shampooing does not impact overall hair loss. Potent corticosteroids and topical tacrolimus are commonly used in all forms of primary cicatricial alopecia and are frequently considered first-line treatments. [10] Antimalarial drugs are commonly used to treat lichen planopilaris. Hydroxychloroquine at a dose of 200 mg twice daily is generally used and is often considered first-line systemic therapy. Improvement is often observed within 6 months. Minoxidil helps maximize the hair growth of the remaining follicles. Recently, JAK inhibitors such as baricitinib and tofacitinib have been used to treat lichen planopilaris.[18][19]

A new scoring system, the lichen planopilaris activity index, has been introduced to monitor treatment response and document disease progression. This system assigns numerical values to subjective and objective markers of the disease: symptoms (pruritus, pain, burning) and signs (erythema, perifollicular erythema, perifollicular scale), a measure of the activity (anagen pull test), and spreading of the condition—statistical comparison of pretreatment and posttreatment responses.

Differential Diagnosis

The most important differential diagnosis may be seborrheic dermatitis, as many patients have a long history of scalp scaling, often diagnosed initially as seborrheic dermatitis. A sudden onset of patchy hair loss on the scalp may be diagnosed as alopecia areata. However, if there's only partial hair loss, perifollicular erythema, and scaling within the patch, lichen planopilaris is considered a diagnosis of high suspicion.

Prognosis

The prognosis of lichen planopilaris can vary widely among affected individuals, influenced by several factors such as the extent and severity of scalp involvement, the presence of associated signs and symptoms, the effectiveness of the treatment regimen, and individual patient characteristics. Overall, alopecia is considered a chronic and progressive condition that can lead to significant morbidity, particularly in cases of extensive and severe disease.

Complications

Some potential complications of lichen planopilaris include:

-

Permanent hair loss (cicatricial alopecia): Lichen planopilaris can result in irreversible destruction of hair follicles, leading to scarring and permanent hair loss in affected areas of the scalp.

-

Scarring and fibrosis: The chronic inflammation characteristic of lichen planopilaris can lead to significant scarring and fibrosis within the affected scalp tissue. This scarring may cause scalp tightness, pain, and discomfort and can also affect the ability of remaining hair follicles, decreasing their functionality.

-

Follicular hyperkeratosis: Lichen planopilaris can accumulate keratin around the hair follicles, leading to hyperkeratosis. This condition may manifest as rough, scaly patches on the scalp, contributing to itching, irritation, and further inflammation.

-

Secondary infections: Persistent inflammation and compromised skin barrier function may subject affected individuals to secondary bacterial or fungal infections of the scalp area. These infections can exacerbate existing symptoms such as itching, pain, and inflammation and may require additional treatment with antibiotics or antifungal medications.

-

Psychological impact: The visible changes associated with lichen planopilaris, including hair loss, scarring, and scalp abnormalities, can have a noteworthy psychological impact on affected individuals, leading to decreased self-esteem, anxiety, and depression. Therefore, managing the psychosocial aspects of lichen planopilaris is an essential component of comprehensive care for these patients.

-

Ocular involvement: In rare cases, lichen planopilaris can extend beyond the scalp and involve the eyebrows and eyelashes. Eyebrow and eyelash loss can occur, leading to cosmetic concerns and potential eye irritation or discomfort.[20]

Early diagnosis, treatment compliance, and close monitoring by dermatologists and multidisciplinary care are necessary to optimize outcomes for individuals with lichen planopilaris.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Deterrence and patient education are important components for effectively managing cases of lichen planopilaris. Providing patients with knowledge about their clinical condition promotes treatment adherence and mitigates potential complications. Patients should be informed about the signs and symptoms of lichen planopilaris, such as scalp itching, burning, and hair loss, to facilitate early recognition and prompt medical evaluation. Encouraging patients to seek medical attention if they notice any concerning changes in their scalp or hair is crucial. Once treatment begins, patients should be counseled to follow treatment with compliance. Addressing the psychosocial impact of the disease through supportive guidance and counseling is also essential.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Lichen planopilaris is best managed by a dermatologist. However, the patient may initially be seen by a primary care clinician. These clinicians must refer patients with complex skin disorders to the respective specialist for treatment. Coordination between this interprofessional team improves outcomes. The primary goals of treatment are to reduce hair loss, control the symptoms, and stop the scarring process. Regrowth should not be expected as the complete elimination of inflammation is unlikely. No consistent markers measure the progress of the disorder. Therapy is based on perceived severity and patient tolerance to treatment. The duration of treatment should be guided by clinical response and relapse rates. General measures include avoiding chemical or physical insults to the hair, such as coloring or perming. Some patients may benefit from hydroxychloroquine and minoxidil, but a complete response is rare. Improvement may take 6 to 9 months or longer.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Ocampo-Garza J, Tosti A. Trichoscopy of Dark Scalp. Skin appendage disorders. 2018 Nov:5(1):1-8. doi: 10.1159/000488885. Epub 2018 Jul 18 [PubMed PMID: 30643773]

Hu AC, Chapman LW, Mesinkovska NA. The efficacy and use of finasteride in women: a systematic review. International journal of dermatology. 2019 Jul:58(7):759-776. doi: 10.1111/ijd.14370. Epub 2019 Jan 3 [PubMed PMID: 30604525]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLee B, Elston DM. The uses of naltrexone in dermatologic conditions. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2019 Jun:80(6):1746-1752. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.12.031. Epub 2018 Dec 21 [PubMed PMID: 30582992]

Fechine COC, Valente NYS, Romiti R. Lichen planopilaris and frontal fibrosing alopecia: review and update of diagnostic and therapeutic features. Anais brasileiros de dermatologia. 2022 May-Jun:97(3):348-357. doi: 10.1016/j.abd.2021.08.008. Epub 2022 Apr 2 [PubMed PMID: 35379508]

Babahosseini H, Tavakolpour S, Mahmoudi H, Balighi K, Teimourpour A, Ghodsi SZ, Abedini R, Ghandi N, Lajevardi V, Kiani A, Kamyab K, Mohammadi M, Daneshpazhooh M. Lichen planopilaris: retrospective study on the characteristics and treatment of 291 patients. The Journal of dermatological treatment. 2019 Sep:30(6):598-604. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2018.1542480. Epub 2019 Jan 4 [PubMed PMID: 30411987]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKelati A, Mernissi FZ. Central Frontoparietal Band-Like Alopecia in a 40-Year-Old Woman. Skin appendage disorders. 2018 Oct:4(4):351-353. doi: 10.1159/000485809. Epub 2018 Jan 19 [PubMed PMID: 30410916]

Uthayakumar AK, Rudd E, Noy M, Weir J, Larkin J, Fearfield L. Severe progressive scarring pembrolizumab-induced lichen planopilaris in a patient with metastatic melanoma. The Australasian journal of dermatology. 2021 Aug:62(3):403-406. doi: 10.1111/ajd.13660. Epub 2021 Jul 3 [PubMed PMID: 34216144]

Garcia-Melendo C, Morales-Munera CE, Dalmau J, Cubiró X, López-Sánchez C, Mozos A, Yélamos O. Extensive lichen planopilaris as exclusive lichenoid reaction secondary to pembrolizumab in a patient with metastatic melanoma. Dermatologic therapy. 2022 May:35(5):e15388. doi: 10.1111/dth.15388. Epub 2022 Feb 24 [PubMed PMID: 35174945]

Lahouel I, Ben Salah N, Rouatbi J, Boukhriss S, Abdejlil N, Youssef M, Belhadjali H, Laatiri A, Zili J. Nilotinib-induced lichen planopilaris. International journal of dermatology. 2022 Jan:61(1):e37-e38. doi: 10.1111/ijd.15647. Epub 2021 May 3 [PubMed PMID: 33937983]

Xie F, Lehman JS. Lichen Planopilaris. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 2022 Feb:97(2):208-209. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2021.11.030. Epub [PubMed PMID: 35120689]

Naeini FF, Saber M, Faghihi G. Lichen planopilaris: A review of evaluation methods. Indian journal of dermatology, venereology and leprology. 2021 May-Jun:87(3):442-445. doi: 10.25259/IJDVL_775_18. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33871194]

Taguti P, Dutra H, Trüeb RM. Lichen Planopilaris Caused by Wig Attachment: A Case of Koebner Phenomenon in Frontal Fibrosing Alopecia. International journal of trichology. 2018 Jul-Aug:10(4):172-174. doi: 10.4103/ijt.ijt_48_18. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30386077]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDoche I, Wilcox GL, Ericson M, Valente NS, Romiti R, McAdams BD, Hordinsky MK. Evidence for neurogenic inflammation in lichen planopilaris and frontal fibrosing alopecia pathogenic mechanism. Experimental dermatology. 2020 Mar:29(3):282-285. doi: 10.1111/exd.13835. Epub 2019 Feb 12 [PubMed PMID: 30408256]

Imhof RL, Chaudhry HM, Larkin SC, Torgerson RR, Tolkachjov SN. Frontal Fibrosing Alopecia in Women: The Mayo Clinic Experience With 148 Patients, 1992-2016. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 2018 Nov:93(11):1581-1588. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.05.036. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30392542]

Nasiri S, Bidari Zerehpoosh F, Abdollahimajd F, Younespour S, Esmaili Azad M. A comparative immunohistochemical study of epidermal and dermal/perifollicular Langerhans cell concentration in discoid lupus erythematosus and lichen planopilaris: a cross-sectional study. Lupus. 2018 Dec:27(14):2200-2205. doi: 10.1177/0961203318808587. Epub 2018 Oct 30 [PubMed PMID: 30376791]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAlessandrini A, Bruni F, Piraccini BM, Starace M. Common causes of hair loss - clinical manifestations, trichoscopy and therapy. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV. 2021 Mar:35(3):629-640. doi: 10.1111/jdv.17079. Epub 2021 Jan 8 [PubMed PMID: 33290611]

Svigos K, Yin L, Fried L, Lo Sicco K, Shapiro J. A Practical Approach to the Diagnosis and Management of Classic Lichen Planopilaris. American journal of clinical dermatology. 2021 Sep:22(5):681-692. doi: 10.1007/s40257-021-00630-7. Epub 2021 Aug 4 [PubMed PMID: 34347282]

Motamed-Sanaye A, Khazaee YF, Shokrgozar M, Alishahi M, Ahramiyanpour N, Amani M. JAK inhibitors in lichen planus: a review of pathogenesis and treatments. The Journal of dermatological treatment. 2022 Dec:33(8):3098-3103. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2022.2116926. Epub 2022 Aug 29 [PubMed PMID: 35997540]

Nasimi M, Ansari MS. JAK Inhibitors in the Treatment of Lichen Planopilaris. Skin appendage disorders. 2024 Feb:10(1):10-17. doi: 10.1159/000534631. Epub 2023 Nov 9 [PubMed PMID: 38313572]

Ruiz-Lozano RE,Hernández-Camarena JC,Valdez-Garcia JE,Roman-Zamudio M,Herrera-Rodriguez MI,Andrade-Carrillo D,Garza-Garza LA,Cardenas-de la Garza JA, Ocular involvement and complications of lichen planus, lichen planus pigmentosus, and lichen planopilaris: A comprehensive review. Dermatologic therapy. 2021 Sep 19; [PubMed PMID: 34541780]