Introduction

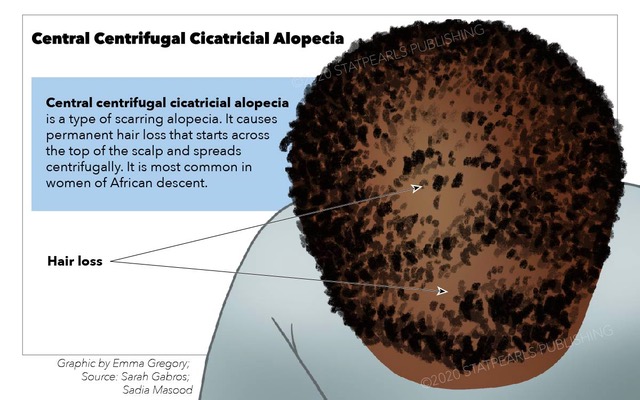

Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA) is a unique form of scarring alopecia that clinically presents as patches of permanent hair loss on the vertex or crown of the scalp and spreads centrifugally.[1] (See Image. Central Centrifugal Cicatricial Alopecia.) This type of hair loss is associated with signs and symptoms of inflammation. CCCA is a common condition that usually affects women of African descent, and it runs in families.[2] Limited data is available regarding the treatment of CCCA. The treatment modalities include topical and systemic corticosteroids and oral tetracyclines with limited response. The prognosis varies, and it widely depends upon the duration and nature of the disease.[3]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The cause of CCCA is unclear. Various theories about the etiology of CCCA are prevalent. One hypothesis suggests a strong association between CCCA and hair care products Black women use, like chemical relaxers, hot combs, and various traction-inducing hairstyles.[4] Over time, this concept was discarded upon recognizing the problem in women not using these hair products. Literature suggests that environmental and genetic factors also affect the etiology.[5]

Other etiologic theories have focused on premature desquamation of the inner root sheath, which allows external factors (eg, chemicals, bacteria) to enter the follicular unit or the hair shaft to irritate the outer root sheath, leading to an inflammatory cascade.[6][7][8] This theory may be supported by pathologic evidence of premature desquamation of the inner root sheath seen on biopsy specimens in CCCA.[6]

Another theory suggests that CCCA may be a fibroproliferative disorder leading to low-level inflammation that causes scarring of the follicle and subsequently inhibits hair growth.[9][10][11] However, current evidence does not support any one of these various theories. As such, the etiology of CCCA is presumed to be multifactorial. Various other suggested causes include infections, autoimmune diseases, or genetic factors. CCCA could be idiopathic, but more studies are needed to clarify this concept.[12]

Epidemiology

Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia is the most common type of cicatricial alopecia among middle-aged women of African descent; it is most common in those with a tightly curled or kinked hair configuration, with a reported prevalence varying between studies from 2% to 7%.[13]. CCCA is uncommon in men and children, though it has been reported in some case studies.[14][15][16] The mean age of onset of the disease in women is 36 years.[5] These are the known characteristics of the disease process, and further population-level studies are needed as most studies are based on data in cities with small samples of patients. Currently, no well-documented published evidence about the involvement of CCCA in other populations is available.[17]

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of CCCA is still not well understood. Results from a study by Sperling and colleagues identified cytokeratin 75 expressions in unaffected and affected tissues.[1] Cytokeratin 75 is usually expressed in the hair follicle between inner and outer root sheaths. They had reduced keratin expression, occurring more prematurely (below the isthmus) within the affected follicles of CCCA compared with normal follicles.[18] However, the expression of cytokeratin 75 in unaffected follicles in cases of CCCA was not different from normal follicles. This suggests that cytokeratin 75 expression can only indicate premature inner hair root sheath desquamation.

As a result, the premature desquamation of the inner root sheath can allow external factors (eg, chemicals, bacteria) to enter the follicular unit or allow the hair shaft to irritate the outer root sheath, leading to an inflammatory cascade.[6][7][8] This theory may be supported by pathologic evidence of premature desquamation of the inner root sheath seen on biopsy specimens in CCCA and the evidence on cytokeratin 75.[6]

Histopathology

The histologic finding found in early cases is premature desquamation of the inner root sheath (PDIRS). Still, the finding is non-specific to CCCA as it is also present in other primary scarring alopecia, where the follicle is damaged due to severe inflammation.[6] However, when slightly inflamed or non-inflamed follicles demonstrate features of PDIRS, then it is suggestive of CCCA.[7] Early histologic changes show perifollicular lymphocytic infiltrate with perifollicular fibroplasia. These inflammatory infiltrates typically extend from the lower follicular infundibulum to the upper part of the isthmus.[19] Few cases present with a reduction of terminal hair follicles. Later stages are associated with follicular epithelium destruction and retention of hair shaft fragments along with granulomatous inflammation. This is followed by follicular epithelium being replaced by connective tissue and tufting/polytrichia of hair follicles (fusion of infundibulum). Histologically, this resembles the early stages of folliculitis keloidalis (FK) and the advanced stage of lichen planopilaris.[20]

History and Physical

History and findings of a clinical examination that help to diagnose central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia include:

- Usually starts at the vertex of the scalp [21]

- Progresses centrifugally, usually in a symmetrical fashion

- Scalp is soft on palpation

- Mild hyperpigmentation around the hair follicles [22]

- Affected patch of alopecia slowly blends with the surrounding normal scalp

- On dermoscopy, observed loss of follicular ostia or a white peripilar halo (a specific marker)[23]

- Mild burning, tenderness, or itching can be confined to area of hair loss

- Islands of unaffected hairs with polytrichia within affected areas

- Historical findings consistent with CCCA (eg, chemical use, African descent, tight hairstyles, hot comb use)

Evaluation

A suspicion of CCCA should be considered in every case of alopecia involving the vertex in female patients of Afro-Caribbean descent.[24] The trichoscopy shows perihilar white halos, loss of follicular openings, disrupted pigmented network, irregularly distributed pinpoint white dots, and individual broken hair follicles.[23] The hair shaft quality can be assessed by checking the length, diameter, and breakage. The blunt tip of hair with broomstick ends suggests breakage or trichorrhexis nodosa. Longitudinal splitting of the hair's distal end and trichoptilosis suggest hair damage secondary to heat or chemical processes.

A hair pull test needs to be performed to rule out telogen effluvium.[25] This test usually yields 2 to 5 telogen hairs on pulling 50 to 100 hairs in a normal adult, but it may be increased up to 3 to 5 times in telogen effluvium. Signs of hyperandrogenism like acne, hirsutism, prolongation of menstrual cycles, and obesity need to be noted as they are associated with female pattern hair loss.[6] A serum total and free testosterone dehydroepiandrostenedione sulfate (DHEAS), prolactin levels, and luteinizing hormone, follicular stimulating hormone ratio helps rule out polycystic ovarian syndrome associated with female pattern hair loss.[26][27]

An extreme elevation in androgens is suggestive of a virilizing tumor. Further, nutritional deficiencies need to be ruled out. This is ascertained by vitamin D levels, serum iron, ferritin, and total iron-binding capacity.[4][25] A baseline complete blood count, renal function test, liver and thyroid function tests, syphilis serology, and antinuclear antibody screening help rule out other minor causes of hair loss.[25] An absence of hyphae in KOH mount from the scalp scraping may help rule out tinea capitis. Finally, two 4-mm punch biopsies (for vertical and horizontal sectioning) from the active margin of the alopecia may help confirm the diagnosis. However, some sources report that one biopsy may be sufficient for diagnosis.[4]

Treatment / Management

Treatment goals include encouraging hair regrowth and preventing or halting the progression of the disease, but hairs will not regrow from permanently damaged hair follicles. Although no clear guidelines exist for the management of CCCA, and most treatment options are only empiric, early intervention reduces the chance of disease progression.[28]

The response of CCCA to various treatment modalities is slow. Anti-inflammatory therapy is often considered the first-line treatment, achieved with topical steroids or intralesional triamcinolone acetonide. A lower concentration of topical steroids decreases the risk of hypopigmentation in people with darker skin types. Antibiotics like tetracyclines (eg, doxycycline) are effective and must be continued until improvement (at least 2-6 months) as they have anti-inflammatory properties.[29] The dose may be decreased and then gradually discontinued after a quiescent state for at least 1 year. Systemic anti-inflammatory treatments like mycophenolate mofetil, hydroxychloroquine, and cyclosporine have also been used in cases of similar scarring alopecias.[30] Short courses of oral corticosteroids are ideal for cases with active inflammation. Vitamin D may also have an effective role in management.[2] Other studies with few subjects have included minoxidil, topical metformin, and tacrolimus.[3][31][32] Minimal hair grooming is recommended, though the evidence is not sufficient. Haircare practices need to be reduced or modified to be briefer. Excessive traction of hairs is better avoided. Symptomatic relief is achieved with the weekly use of mild shampooing.[3](B2)

Differential Diagnosis

Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia clinically resembles:

- Female pattern hair loss: A form of nonscarring alopecia occurring after menopause or at puberty, associated with hyperandrogenism. The key feature to differentiate it from CCCA is the absence of scarring and the presence of visible follicular openings.[33]

- Lichen planopilaris: This is a type of scarring alopecia that is also indistinguishable in some cases. In contrast to central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia, lichen planopilaris presents with perifollicular erythema and follicular keratosis. Frontal fibrosing alopecia is another form of lichen planopilaris. This is characterized by facial papules and slowly progressive scarring alopecia of the scalp. Alopecia also affects the eyelashes, eyebrows, and other body parts.[34]

- Tinea capitis: This is a fungal infective condition of the scalp, differentiated by Wood lamp examination, which emits bright green fluorescence with microsporum and faint blue fluorescence with Trichophyton schoenleinii species. The condition presents with both scarring and non-scarring alopecia.

- Discoid lupus erythematosus: This is a form of scarring alopecia that usually affects the scalp; it appears as erythematous scaly plaques with follicular plugging along with pigmentary changes. The histological findings differentiate this condition from CCCA. Histopathology shows perivascular and periadnexal lymphohistiocytic infiltrate and interface dermatitis.[34] The basal layer shows degenerative changes.

- Pseudopelade of Brocq: This condition usually affects middle-aged and older women and commonly presents as irregular patches of hair loss that usually begin at the vertex. The bald areas look like 'footprints in the snow.' Histopathology of the lesion shows a thin epidermis with sclerotic dermis and streamers of fibrosis that go up to the fat layer.[35]

Lichen planopilaris presents with superficial perifollicular fibrosis, infundibular inflammation, and destruction, leading to free hair shafts in the dermis, similar to central centrifugal alopecia. Still, it is differentiated by vacuolar lichenoid dermatitis with epidermal cytoid bodies and peri-infundibular hypergranulosis. Dyskeratosis with perifollicular lymphocytic inflammation is a prevalent feature. A gradual progressive hair follicle loss with lymphohistiocytic infiltration and lamellar fibrosis around the isthmus and lower infundibulum is seen in frontal fibrosing alopecia.[2]

Staging

A photographic scale has been in use for staging alopecia in African-American women. The central scalp alopecia scale used for African-American women helps assess the severity of hair loss in CCCA. This condition is graded on a scale of 0 to 5. Grade 0 suggests normal hair density, and grade 5 suggestive of severe alopecia.[36]

Prognosis

The prognosis of CCCA depends on the stage of the disease. Early diagnosis and standard treatment may be able to enhance hair regrowth.[37] The prognosis for patients with advanced disease is poor due to late diagnosis and treatment, which may result in only slight potential for hair regrowth due to scarring.[1]

Complications

The most common problems associated with CCCA relate to late or misdiagnosis. CCCA is a scarring alopecia, and restoring the amount of hair already damaged is difficult. Symptoms usually vary from none to very disruptive and present with burning, itching, and tenderness. Treatment aims to preserve the remaining hairs and avoid disease progression. The severity of the condition and the available treatment options must be clearly explained to the patient.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patient education is essential in alleviating the anxiety associated with central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia, and well-informed patients can learn to be confident in managing their condition. The scarring stage requires emphasizing that no cure exists, but it can be controlled and managed. Patients should avoid hair practices that need heat treatment or provide friction. The regular use of hair relaxers should be avoided, as it leads to increased disease incidence. Patients (and their clinicians) should be encouraged to participate in various support groups and hair advocacy organizations.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Consider the impact of CCCA on psychosocial functioning and quality of life, and remember that it may accompany psychological distress.[38] The dermatologist and pharmacist can help to promote the appropriate use of topical corticosteroids and employ steroid-sparing alternatives. Hair transplantation can be an effective strategy in patients with advanced disease, although a chance that scarring may reduce the survival rate of transplanted grafts exists. Patients may need psychological support and be encouraged to join various disease support groups.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Flamm A, Moshiri AS, Roche F, Onyekaba G, Nguyen J, James AJ, Taylor S, Seykora JT. Characterization of the inflammatory features of central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. Journal of cutaneous pathology. 2020 Jun:47(6):530-534. doi: 10.1111/cup.13666. Epub 2020 Mar 6 [PubMed PMID: 32068905]

Aguh C. Updates in our understanding of central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. Cutis. 2019 Dec:104(6):316;340 [PubMed PMID: 31939927]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAraoye EF, Thomas JAL, Aguh CU. Hair regrowth in 2 patients with recalcitrant central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia after use of topical metformin. JAAD case reports. 2020 Feb:6(2):106-108. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.12.008. Epub 2020 Jan 22 [PubMed PMID: 32016152]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSundberg JP, Hordinsky MK, Bergfeld W, Lenzy YM, McMichael AJ, Christiano AM, McGregor T, Stenn KS, Sivamani RK, Pratt CH, King LE Jr. Cicatricial Alopecia Research Foundation meeting, May 2016: Progress towards the diagnosis, treatment and cure of primary cicatricial alopecias. Experimental dermatology. 2018 Mar:27(3):302-310. doi: 10.1111/exd.13495. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29341265]

Malki L, Sarig O, Romano MT, Méchin MC, Peled A, Pavlovsky M, Warshauer E, Samuelov L, Uwakwe L, Briskin V, Mohamad J, Gat A, Isakov O, Rabinowitz T, Shomron N, Adir N, Simon M, McMichael A, Dlova NC, Betz RC, Sprecher E. Variant PADI3 in Central Centrifugal Cicatricial Alopecia. The New England journal of medicine. 2019 Feb 28:380(9):833-841. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1816614. Epub 2019 Feb 13 [PubMed PMID: 30763140]

Tan T, Guitart J, Gerami P, Yazdan P. Premature Desquamation of the Inner Root Sheath in Noninflamed Hair Follicles as a Specific Marker for Central Centrifugal Cicatricial Alopecia. The American Journal of dermatopathology. 2019 May:41(5):350-354. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0000000000001336. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30562220]

Miteva M, Tosti A. Pathologic diagnosis of central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia on horizontal sections. The American Journal of dermatopathology. 2014 Nov:36(11):859-64; quiz 865-7. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0000000000000174. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25222198]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMiteva M, Tosti A. 'A detective look' at hair biopsies from African-American patients. The British journal of dermatology. 2012 Jun:166(6):1289-94. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.10892.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22348354]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSamrao A, Lyon L, Mirmirani P. Evaluating the association of central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA) and fibroproliferative disorders. Dermatology online journal. 2021 Aug 15:27(8):. doi: 10.5070/D327854688. Epub 2021 Aug 15 [PubMed PMID: 34755957]

Aguh C, Dina Y, Talbot CC Jr, Garza L. Fibroproliferative genes are preferentially expressed in central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2018 Nov:79(5):904-912.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.05.1257. Epub 2018 Jun 18 [PubMed PMID: 29913259]

Jamerson TA, Talbot CC Jr, Dina Y, Aguh C. Presence of Uterine Leiomyomas Has No Significant Impact on Gene Expression Profile in the Scalp of Patients with Central Centrifugal Cicatricial Alopecia. JID innovations : skin science from molecules to population health. 2022 Jan:2(1):100060. doi: 10.1016/j.xjidi.2021.100060. Epub 2021 Oct 6 [PubMed PMID: 35024684]

Anzai A, Wang EHC, Lee EY, Aoki V, Christiano AM. Pathomechanisms of immune-mediated alopecia. International immunology. 2019 Jul 13:31(7):439-447. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxz039. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31050755]

Herskovitz I, Miteva M. Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: challenges and solutions. Clinical, cosmetic and investigational dermatology. 2016:9():175-81. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S100816. Epub 2016 Aug 17 [PubMed PMID: 27574457]

Eginli AN, Dlova NC, McMichael A. Central Centrifugal Cicatricial Alopecia in Children: A Case Series and Review of the Literature. Pediatric dermatology. 2017 Mar:34(2):133-137. doi: 10.1111/pde.13046. Epub 2016 Dec 16 [PubMed PMID: 27981623]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDavis EC, Reid SD, Callender VD, Sperling LC. Differentiating central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia and androgenetic alopecia in african american men: report of three cases. The Journal of clinical and aesthetic dermatology. 2012 Jun:5(6):37-40 [PubMed PMID: 22768355]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSperling LC, Skelton HG 3rd, Smith KJ, Sau P, Friedman K. Follicular degeneration syndrome in men. Archives of dermatology. 1994 Jun:130(6):763-9 [PubMed PMID: 8002648]

Akintilo L, Hahn EA, Yu JMA, Patterson SSL. Health care barriers and quality of life in central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia patients. Cutis. 2018 Dec:102(6):427-432 [PubMed PMID: 30657802]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSperling LC, Hussey S, Sorrells T, Wang JA, Darling T. Cytokeratin 75 expression in central, centrifugal, cicatricial alopecia--new observations in normal and diseased hair follicles. Journal of cutaneous pathology. 2010 Feb:37(2):243-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2009.01330.x. Epub 2009 Jul 10 [PubMed PMID: 19614992]

Heath CR, Usatine RP. Central Centrifugal Cicatricial Alopecia. Cutis. 2022 Apr:109(4):235-236. doi: 10.12788/cutis.0490. Epub [PubMed PMID: 35659847]

Fernandez-Flores A. Use of Giemsa staining in the evaluation of central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. Journal of cutaneous pathology. 2020 May:47(5):496-499. doi: 10.1111/cup.13667. Epub 2020 Feb 24 [PubMed PMID: 32065424]

Miteva M, Tosti A. Central Centrifugal Cicatricial Alopecia Presenting with Irregular Patchy Alopecia on the Lateral and Posterior Scalp. Skin appendage disorders. 2015 Mar:1(1):1-5. doi: 10.1159/000370315. Epub 2015 Jan 7 [PubMed PMID: 27172374]

Griggs J, Trüeb RM, Gavazzoni Dias MFR, Hordinsky M, Tosti A. Fibrosing alopecia in a pattern distribution. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2021 Dec:85(6):1557-1564. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.12.056. Epub 2020 Jan 8 [PubMed PMID: 31926219]

Miteva M, Tosti A. Dermatoscopic features of central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2014 Sep:71(3):443-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.04.069. Epub 2014 Jun 11 [PubMed PMID: 24929886]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSu HJ, Cheng AY, Liu CH, Chu CB, Lee CN, Hsu CK, Lee JY, Yang CC. Primary scarring alopecia: A retrospective study of 89 patients in Taiwan. The Journal of dermatology. 2018 Apr:45(4):450-455. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.14217. Epub 2018 Jan 16 [PubMed PMID: 29341216]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWu S. Hair and Nail Conditions: Alopecia Evaluation. FP essentials. 2022 Jun:517():11-16 [PubMed PMID: 35679467]

Jiang VS, Hawkins SD, McMichael A. Female pattern hair loss and polycystic ovarian syndrome: more than just hirsutism. Current opinion in endocrinology, diabetes, and obesity. 2022 Dec 1:29(6):535-540. doi: 10.1097/MED.0000000000000777. Epub 2022 Oct 13 [PubMed PMID: 36226726]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCarmina E, Azziz R, Bergfeld W, Escobar-Morreale HF, Futterweit W, Huddleston H, Lobo R, Olsen E. Female Pattern Hair Loss and Androgen Excess: A Report From the Multidisciplinary Androgen Excess and PCOS Committee. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2019 Jul 1:104(7):2875-2891. doi: 10.1210/jc.2018-02548. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30785992]

Bolduc C, Sperling LC, Shapiro J. Primary cicatricial alopecia: Other lymphocytic primary cicatricial alopecias and neutrophilic and mixed primary cicatricial alopecias. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2016 Dec:75(6):1101-1117. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.01.056. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27846945]

George EA, Matthews C, Roche FC, Taylor SC. Beyond the Hot Comb: Updates in Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, and Treatment of Central Centrifugal Cicatricial Alopecia from 2011 to 2021. American journal of clinical dermatology. 2023 Jan:24(1):81-88. doi: 10.1007/s40257-022-00740-w. Epub 2022 Nov 18 [PubMed PMID: 36399228]

Fagan N, Meah N, York K, Bokhari L, Fletcher G, Chen G, Tobin DJ, Messenger A, Irvine AD, Sinclair R, Wall D. Shedding light on therapeutics in alopecia and their relevance to COVID-19. Clinics in dermatology. 2021 Jan-Feb:39(1):76-83. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2020.12.015. Epub 2020 Dec 16 [PubMed PMID: 33972056]

Lobon K, Pinczewski J, Bhoyrul B. Significant hair regrowth in a Middle Eastern woman with central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. Clinical and experimental dermatology. 2022 Jan:47(1):136-138. doi: 10.1111/ced.14822. Epub 2021 Aug 23 [PubMed PMID: 34192377]

Umar S, Kan P, Carter MJ, Shitabata P, Novosilska M. Lichen Planopilaris Responsive to a Novel Phytoactive Botanical Treatment: A Case Series. Dermatology and therapy. 2022 Jul:12(7):1697-1710. doi: 10.1007/s13555-022-00749-3. Epub 2022 Jun 8 [PubMed PMID: 35674981]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRogers N. Imposters of androgenetic alopecia: diagnostic pearls for the hair restoration surgeon. Facial plastic surgery clinics of North America. 2013 Aug:21(3):325-34. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2013.04.002. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24017974]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCallender VD, Wright DR, Davis EC, Sperling LC. Hair breakage as a presenting sign of early or occult central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: clinicopathologic findings in 9 patients. Archives of dermatology. 2012 Sep:148(9):1047-52. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2011.3428. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22986858]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFernandez-Nieto D, Saceda-Corralo D, Jimenez-Cauhe J, Pindado-Ortega C, Erana I, Moreno-Arrones OM, Vano-Galvan S. Central Centrifugal Cicatricial Alopecia in a Fair Phototype Patient. International journal of trichology. 2019 Nov-Dec:11(6):251-252. doi: 10.4103/ijt.ijt_77_19. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32030062]

Fung MA, Sharon VR, Ratnarathorn M, Konia TH, Barr KL, Mirmirani P. Elastin staining patterns in primary cicatricial alopecia. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2013 Nov:69(5):776-782. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.07.018. Epub 2013 Sep 10 [PubMed PMID: 24035210]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceEginli A, Dothard E, Bagayoko CW, Huang K, Daniel A, McMichael AJ. A Retrospective Review of Treatment Results for Patients With Central Centrifugal Cicatrical Alopecia. Journal of drugs in dermatology : JDD. 2017 Apr 1:16(4):317-320 [PubMed PMID: 28403264]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePärna E, Aluoja A, Kingo K. Quality of life and emotional state in chronic skin disease. Acta dermato-venereologica. 2015 Mar:95(3):312-6. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1920. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24978135]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence