Introduction

Aortic stenosis (AS) is caused by progressive calficiation of the valve and is the most common cause of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction. Once moderate AS is present, there is a high liklihood of progression to severe AS. Surgical aortic valve replacement has been the standard treatment for patients with severe symptomatic AS. Previously, patients determined to be at high risk for surgery could only be offered diuretics and balloon valvuloplasty which served as palliative treatment and had no effect on long-term outcomes. The development of transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) has emerged as a lifeline for patients considered to be inoperable providing both improvement in symptoms and statistically significant mortality benefit.[1][2][3]

The concept of transcatheter balloon expandable valves was first introduced in the 1980s by a Danish researcher by the name of H. R. Anderson who began testing this idea on pigs. In 2002, Dr. Alain Cribier performed the first successful percutaneous aortic valve replacement on an inoperable patient. The first approval of TAVR for the indication of severe AS in prohibitive risk patients came in 2011. In 2012, the FDA approved TAVR in patients at high surgical risk. In 2015 the indication was expanded to include “valve-in-valve” procedure for failed surgical bioprosthetic valves. In 2016 the FDA approved TAVR valves for use in patients with severe AS at intermediate risk. Following the results of the PARTNER-3 trial published in 2019, the FDA further expanded the indication for TAVR valves to include low risk patients.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

The normal aortic valve is one of two semilunar valves and separates the left ventricle from the aorta. It is comprised of three leaflets/cusps (left coronary, right coronary and non-coronary cusp) that are attached to an aortic annulus normally opening to approximately 3-5 cm². Transthoracic echocardiography is typically used to evaluate the aortic valve, however additional imaging modalities including transesophageal echocardiography and CT are also commonly used. An aortic valve is considered severely stenotic when it opens to an area of ≤1.0 cm². High gradient AS is the most common form of severe AS and is defined by the mean gradient of ≥40 mmHg and an aortic jet velocity of >4 m/s across the valve. Low flow, low gradient severe AS is a less common form of severe AS. This subset of patients has low flow rate across the valve either due to systolic dysfunction with reduced ejection fraction or small ventricular volumes secondary to left ventricular hypertrophy (with normal LVEF). When LVEF is normal, low flow is defined as a stroke volume index =35 mL/m². Patients with low flow and depressed LVEF undergo dobutamine stress echocardiogram to differentiate true severe stenosis from pseudostenosis (inadequate valve cusp opening caused by low cardiac output causing an artefactually low value).

Indications

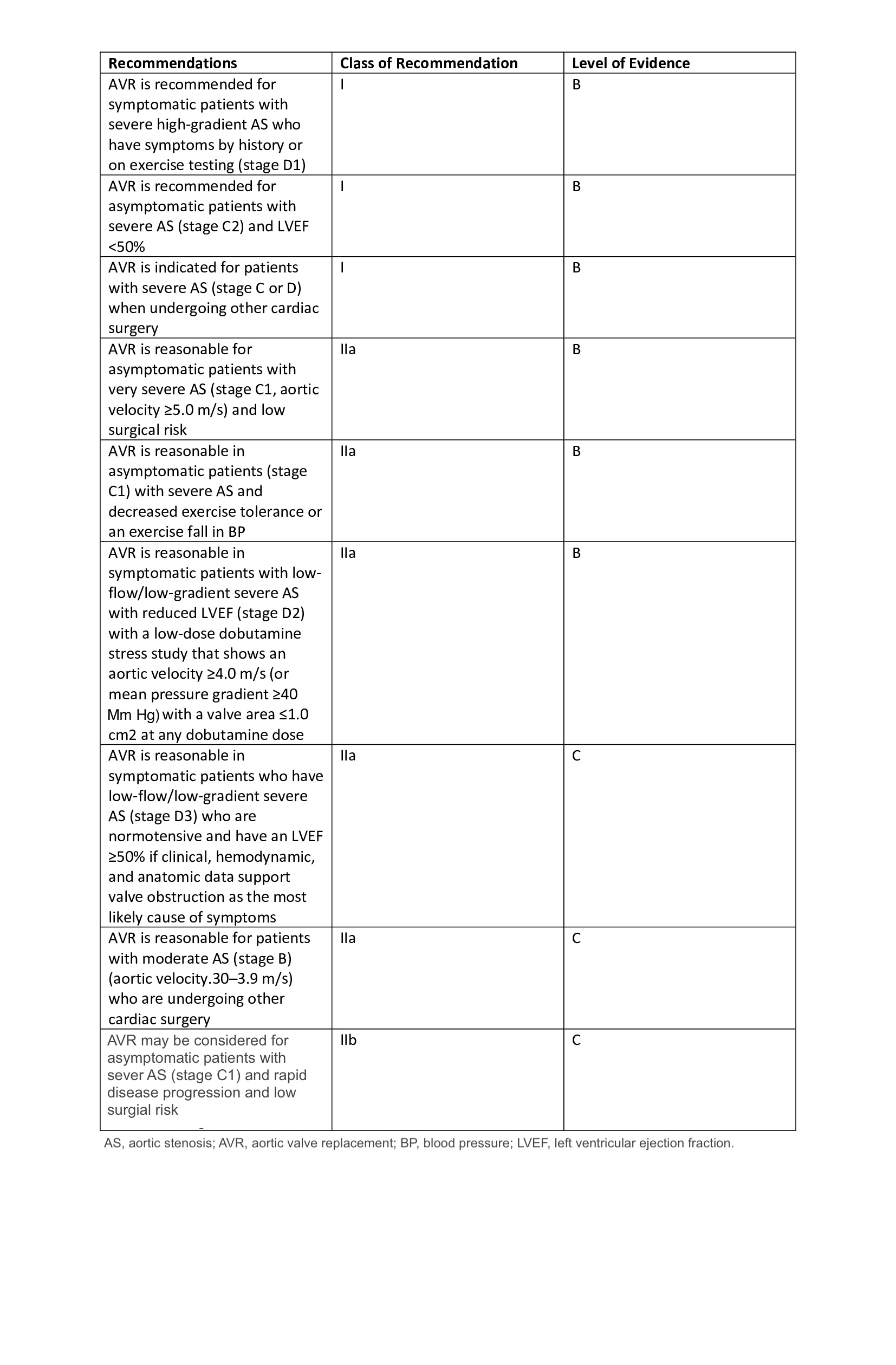

Indications for aortic valve replacement (surgical or transcatheter) are as follows:

-

Severe high-gradient AS with symptoms (class I recommendation, level B evidence)

-

Asymptomatic patients with severe AS and LVEF < 50 (class I recommendation, level B evidence)

-

Severe AS when undergoing other cardiac surgery (class I recommendation, level B evidence)

-

Asymptomatic severe AS and low surgical risk (class IIa recommendation, level B evidence)

-

Symptomatic with low-flow/low-gradient severe AS (class IIa recommendation, level B evidence)

-

Moderate AS and undergoing other cardiac surgery (class IIa recommendation, level C evidence)

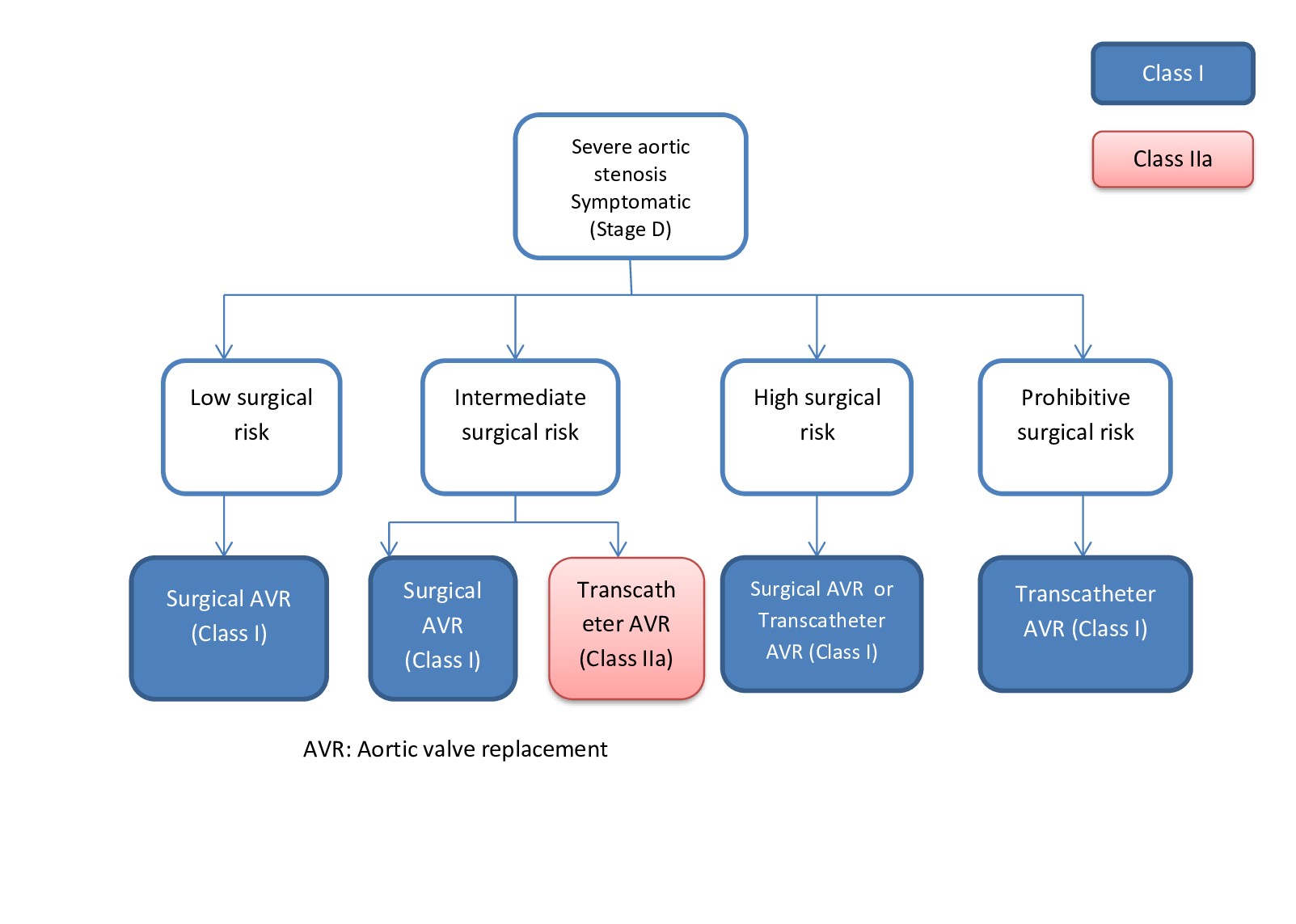

TAVR is approved for the following:

-

Low to prohibitive surgical risk patients with severe AS

- Valve-in-valve procedures for failed prior bioprosthetic valves

Contraindications

Life expectancy less than 12 months owing to a noncardiac cause, myocardial infarction within the last thirty days, congenital unicuspid, bicuspid or noncalcified valve, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, short distance between the annulus and coronary ostium, need for emergency surgery, left ventricular ejection fraction less than 20%, severe pulmonary hypertension with right ventricular dysfunction, echocardiographic evidence of intracardiac mass, thrombus or vegetation, native aortic annulus smaller than 18 or larger than 25 mm, severe mitral regurgitation, MRI confirmed CVA or TIA within last six months, end-stage renal disease, mixed aortic valve disease (concomitant aortic regurgitation), or significant aortic disease.[4]

Personnel

A multidisciplinary team is needed for the TAVR procedure as well as follow up care. The procedural team typically consists of an interventional cardiologist specially trained in TAVR, a cardiac surgeon, an echocardiographic imaging specialist, skilled nurses and a cardiac anesthesiologist if more than conscious sedation is to be administered. Cardiac electrophysiologists, neurologists, nephrologists and vascular surgeons must be readily available if complications from the procedure arise.

Preparation

An interprofessional heart team evaluates patients and puts them through extensive evaluation and pre-procedural testing to determine candidacy before undergoing a TAVR. The heart team consists of cardiologists, cardiothoracic surgeons and anesthesiologists. In addition to transthoracic echocardiography, transesophageal echocardiography is often utilized for better visualization of aortic valve anatomy. Computed tomography angiography (CTA) of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis are also performed for accurate measurement of the aortic annulus for determination of valve size. CTA is also essential for visualization of the vascular anatomy and determination of the approach to be taken. Left heart catheterization is commonly done prior to TAVR to provide invasive hemodynamic measurements as well as rule out any coexisting cornary artery disease (CAD) that may be contributing to symptoms or may need revascularization before determination of either surgical or transcatheter approach. Factors that may influence the decision to pursue surgical aortic valve replacement include the need for concomitant coronary artery bypass grafting. Revascularization of stable CAD prior/during TAVR was previously a subject of debate, however data published in 2019 showed revascularization in conjunction with TAVR failed to offer additional clinical advantage and did not improve important clinical outcomes (risk of MI, stroke or death at 30 days).[5]

Technique or Treatment

Multiple transcatheter aortic valves are available on the market. However, the only two currently FDA-approved for use in the United States are the SAPIEN valves (Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA) and the CORE valves (Medtronic Fridley, MN). The SAPIEN valves are composed of bovine pericardial tissue and a chromium cobalt alloy frame. The SAPIEN valves are balloon expandable. The newest generation Medtronic valve is the EVOLUT-R. It is composed of porcine tissue and a nitinol frame. This valve has the advantage of being self-expandable (not requiring balloon expansion) and has the ability for repositioning after deployment. To date, there have not been any head-to-head trials comparing these two TAVR valves.[6][7][8]

The procedure is typically done in a hybrid room with both operating room and cath lab capabilities. The team consists of interventional cardiologist, cardiac surgeon, and anesthesiologist. The procedure is done under direct visualization with fluoroscopy and occasionally transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) guidance. The most preferred and least invasive approach is the transfemoral approach. If not feasible, an alternate an often more invasive method may need to be used (subclavian, apical, trans-aortic).

Complications

Possible complications to TAVR include conduction disturbances and the need for a permanent pacemaker, stroke, paravalvular leak, vascular site complications, bleeding, annular rupture, left ventricular perforation, cardiac tamponade, need for surgery, acute myocardial infarction, acute kidney injury, infection, hypotension, and death.

A recent meta-analysis revealed statistically significant evidence of lower rates of both acute kidney injury and major bleeding, and a non-statistically significant trend favoring TAVR over SAVR on overall mortality and stroke. Additionally, there was a statistically significant reduction in length of stay. To the contrary, TAVR was associated with higher rates of vascular injury, paravalvular regurgitation and the need for permanent pacemaker placement. One caveat, being that high-risk patients in the TAVR cohort of the PARTNER 1-A trial had higher rates of stroke.[9][10][11]

Clinical Significance

Transcatheter aortic valve replacement is well established in the treatment of severe symptomatic aortic stenosis (AS) for patients considered to be at prohibitive risk for surgery. It is also an alternative to surgical correction in low to intermediate risk patients.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

For patients with severe aortic stenosis who are not candidates for open heart surgery, an alternative is transcatheter aortic valve replacement. The procedure is done by an interprofessional team that involves a cardiac surgeon, an interventional cardiologist, anesthesiologist and a radiologist. After the procedure, the patient needs monitoring in a cardiac ICU by critical care nurses. Such an approach may provide the best results with minimal morbidity. TAVR has now been done in thousands of patients in the US and Europe with a procedural success rate of 90%. The 30 day mortality rates have varied from 3-15%. At 2 years, some studies have shown mortality rates of about 35%. Early deaths are usually due to arrhythmias, heart failure and pulmonary complications. It should be emphasized that TAVR is only for patients deemed at high risk for an open procedure. [12][13][14](Level II)

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Zoltowska DM, Agrawal Y, Patel N, Sareen N, Kalavakunta JK, Gupta V, Halabi A. Association Between Pulmonary Hypertension and Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement: Analysis of a Nationwide Inpatient Sample Database. Reviews on recent clinical trials. 2019:14(1):56-60. doi: 10.2174/1574887113666181120113034. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30457054]

Iantorno M, Ben-Dor I, Rogers T, Gajanana D, Attaran S, Buchanan KD, Satler LF, Shults CC, Thourani VH, Waksman R. Emergent valve-in-valve transcatheter aortic valve replacement in patient with acute aortic regurgitation and cardiogenic shock with preoperative extracorporeal membrane oxygenator: A case report and review of the literature. Cardiovascular revascularization medicine : including molecular interventions. 2018 Dec:19(8S):68-70. doi: 10.1016/j.carrev.2018.11.007. Epub 2018 Nov 12 [PubMed PMID: 30455139]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHenn MC, Zajarias A, Quader N, Sintek M, Lasala JM, Koogler K, Damiano MS, Kachroo P, Miller DC, King CR, Melby SJ, Moon MR, Damiano RJ Jr, Maniar HS. Observed to expected 30-day mortality as a benchmark for transcatheter aortic valve replacement. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2019 Mar:157(3):874-882.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2018.06.097. Epub 2018 Jul 27 [PubMed PMID: 30454980]

Wilson R, McNabney C, Weir-McCall JR, Sellers S, Blanke P, Leipsic JA. Transcatheter Aortic and Mitral Valve Replacements. Radiologic clinics of North America. 2019 Jan:57(1):165-178. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2018.08.001. Epub 2018 Oct 31 [PubMed PMID: 30454811]

Lateef N, Khan MS, Deo SV, Yamani N, Riaz H, Virk HUH, Khan SU, Hedrick DP, Kanaan A, Reed GW, Krishnaswamy A, Puri R, Kapadia SR, Kalra A. Meta-Analysis Comparing Outcomes in Patients Undergoing Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation With Versus Without Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. The American journal of cardiology. 2019 Dec 1:124(11):1757-1764. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2019.08.024. Epub 2019 Sep 26 [PubMed PMID: 31575422]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceEdelman JJ, Thourani VH. Transcatheter aortic valve replacement and surgical aortic valve replacement: Both excellent therapies. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2018 Dec:156(6):2135-2137. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2018.07.065. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30449571]

Gillam LD, Marcoff L. Echocardiographic Assessment of Transcatheter Aortic Valve Hemodynamics: More Tools for the Toolbox. JACC. Cardiovascular imaging. 2019 Jan:12(1):35-37. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2018.05.015. Epub 2018 Nov 15 [PubMed PMID: 30448141]

Chetcuti SJ, Deeb GM, Popma JJ, Yakubov SJ, Grossman PM, Patel HJ, Casale A, Dauerman HL, Resar JR, Boulware MJ, Dries-Devlin JL, Li S, Oh JK, Reardon MJ. Self-Expanding Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement in Patients With Low-Gradient Aortic Stenosis. JACC. Cardiovascular imaging. 2019 Jan:12(1):67-80. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2018.07.028. Epub 2018 Nov 15 [PubMed PMID: 30448116]

Coughlan JJ, Kiernan T, Mylotte D, Arnous S. Annular Rupture During Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation: Predictors, Management and Outcomes. Interventional cardiology (London, England). 2018 Sep:13(3):140-144. doi: 10.15420/icr.2018.20.2. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30443272]

Ando T, Adegbala O, Villablanca PA, Briasoulis A, Takagi H, Grines CL, Schreiber T, Nazif T, Kodali S, Afonso L. In-hospital outcomes of transcatheter versus surgical aortic valve replacement in non-teaching hospitals. Catheterization and cardiovascular interventions : official journal of the Society for Cardiac Angiography & Interventions. 2019 Apr 1:93(5):954-962. doi: 10.1002/ccd.27968. Epub 2018 Nov 8 [PubMed PMID: 30408309]

Rodés-Cabau J, Sacco RL. Neurological Complications Following Aortic Valve Replacement: TAVR Better Than SAVR, But Room for Improvement. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2018 Oct 30:72(18):2120-2122. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.06.080. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30360821]

Chen S, Redfors B, Ben-Yehuda O, Crowley A, Greason KL, Alu MC, Finn MT, Vahl TP, Nazif T, Thourani VH, Suri RM, Svensson L, Webb JG, Kodali SK, Leon MB. Transcatheter Versus Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement in Patients With Prior Cardiac Surgery in the Randomized PARTNER 2A Trial. JACC. Cardiovascular interventions. 2018 Nov 12:11(21):2207-2216. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2018.08.006. Epub 2018 Aug 28 [PubMed PMID: 30409278]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSpaziano M, Lefèvre T, Romano M, Eltchaninoff H, Leprince P, Motreff P, Iung B, Van Belle E, Koning R, Verhoye JP, Gilard M, Garot P, Hovasse T, Le Breton H, Chevalier B. Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement in the Catheterization Laboratory Versus Hybrid Operating Room: Insights From the FRANCE TAVI Registry. JACC. Cardiovascular interventions. 2018 Nov 12:11(21):2195-2203. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2018.06.043. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30409276]

Egger F, Zweiker D, Freynhofer MK, Löffler V, Rohla M, Geppert A, Farhan S, Vogel B, Falkensammer J, Kastner J, Pichler P, Vock P, Lamm G, Luha O, Schmidt A, Scherr D, Hammerer M, Hoppe UC, Maurer E, Grund M, Lambert T, Tkalec W, Sturmberger T, Zeindlhofer E, Grabenwöger M, Huber K, Austrian TAVI Group. Impact of On-Site Cardiac Surgery on Clinical Outcomes After Transfemoral Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. JACC. Cardiovascular interventions. 2018 Nov 12:11(21):2160-2167. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2018.07.015. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30409272]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence