Introduction

Breast ultrasound has developed into a practical solution for the evaluation of breast disease. Although mammography remains the gold standard for breast cancer screening, it presents certain imaging limitations with dense breast parenchyma. Due to this, ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have been expanding their role as part of supplementary breast screening procedures.[1]

The sensitivity for breast cancer detection using both mammography and ultrasound increases to 97.3%, with the false positive rate of ultrasound estimated as 2.4%.[2]

Guidelines regarding breast sonography terminology are presented in the 2013 ACR BI-RADS Atlas. Multiple descriptions of breast findings' features, with a final assessment, often depend on the most concerning characteristic.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

Breast ultrasound is often used to localize palpable and nonpalpable masses before surgical excision.[3]

The basic breast anatomy comprises 15 to 20 lobules, each consisting of smaller breast ducts, known as the terminal duct lobular units (TDLUs). All the ducts drain into a single lactiferous sinus towards the nipple.

The three main anatomical zones of the breast are the premammary, mammary, and retromammary zones, which consist of fatty, fibroglandular, and muscular tissue. Breast fat and fibroglandular tissue lie between the superficial fascia immediately deep to the skin and the deep fascial layer superficial to the pectoralis muscle.

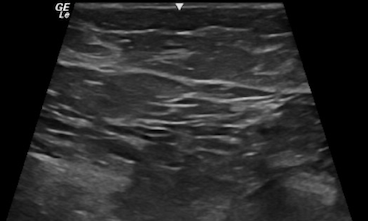

From a sonographic point of view, the breast is divided into various hypoechoic and hyperechoic layers (see Image. Sonographic Cross-Sectional View of Benign Breast Tissue with Typical Hyperechoic, Hypoechoic Layers of Skin, Fat, Fibroglandular and Muscle):

- Skin (hyperechoic, white fibrous bands)

- Fat (hypoechoic, subcutaneous fat lobules)

- Breast parenchyma (hyperechoic, fibroglandular soft tissue)

- Retromammary fat (hypoechoic fat lobules)

- Pectoralis major muscle (hyperechoic fibrous tissue) [4]

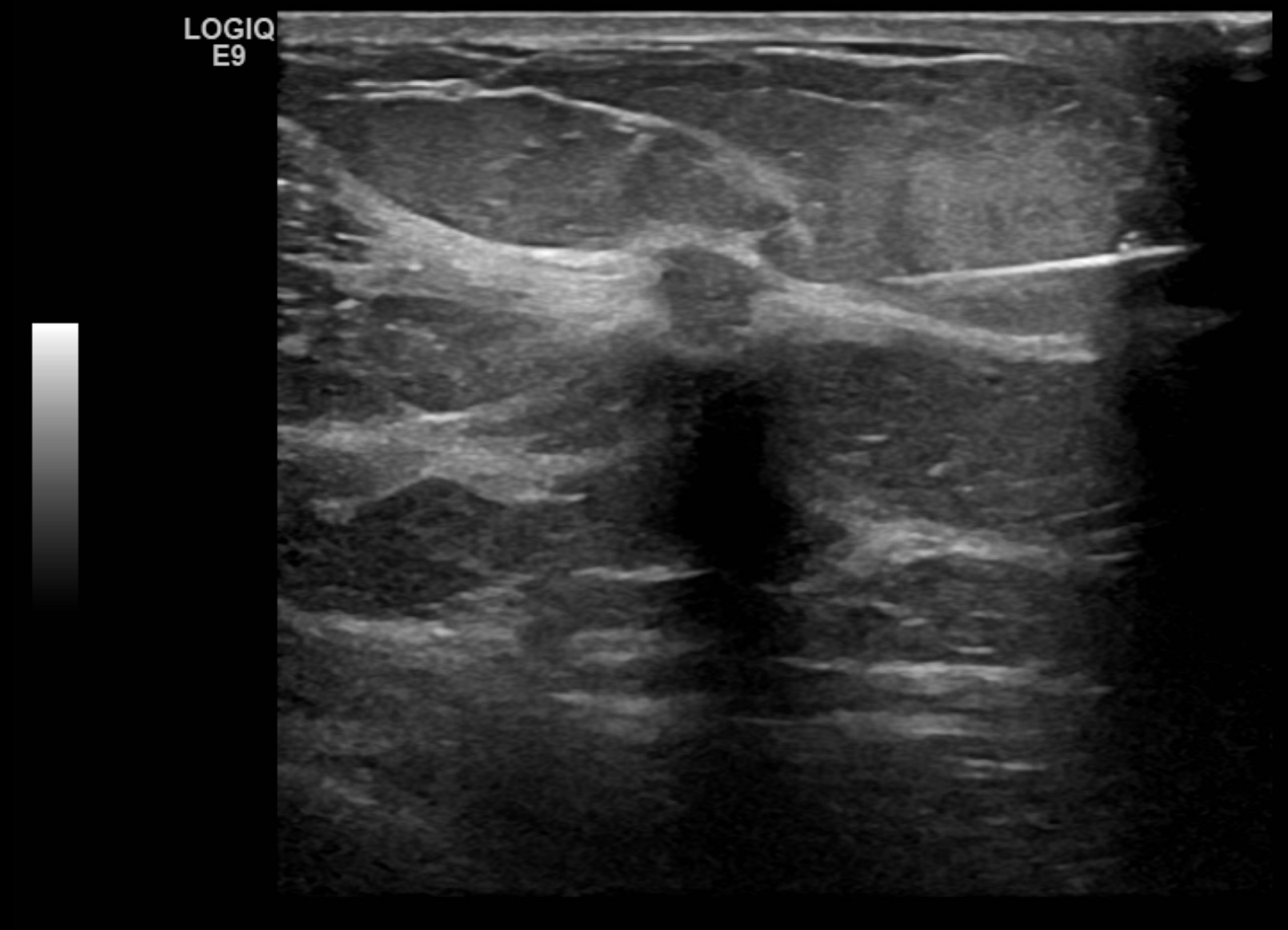

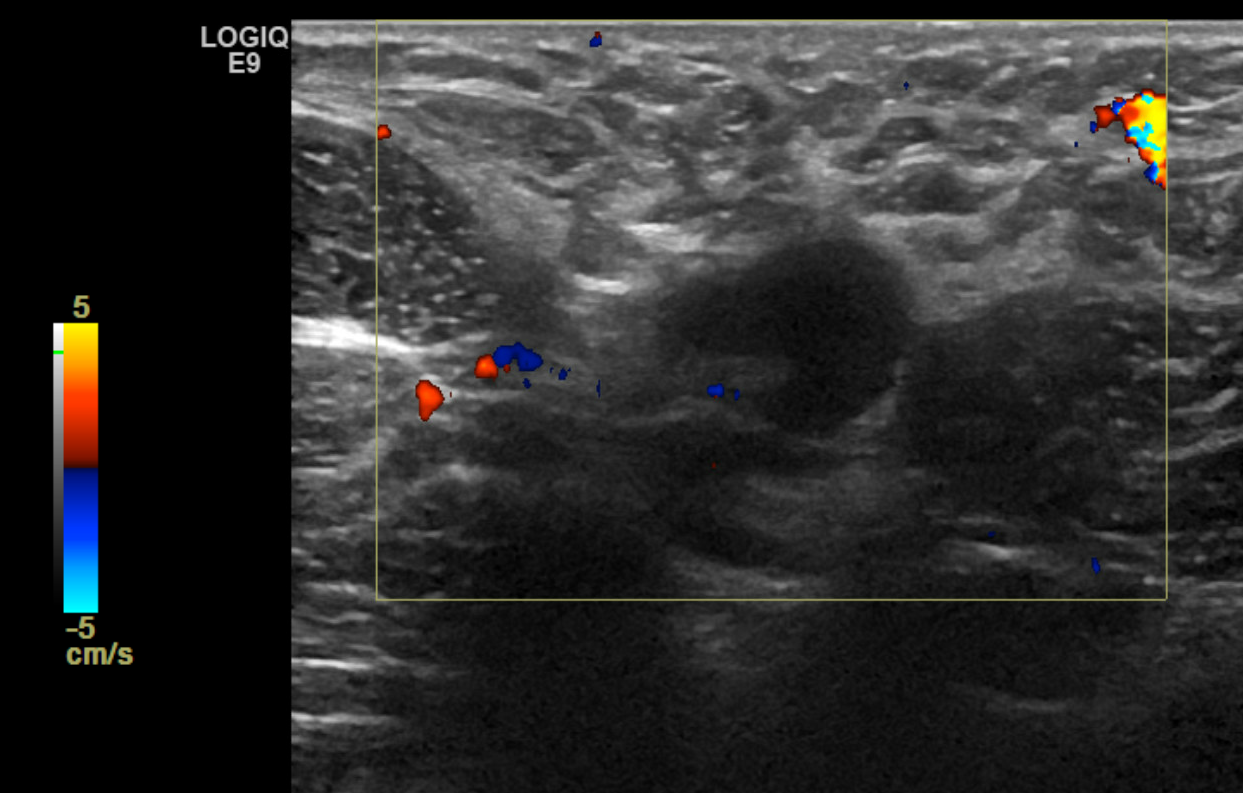

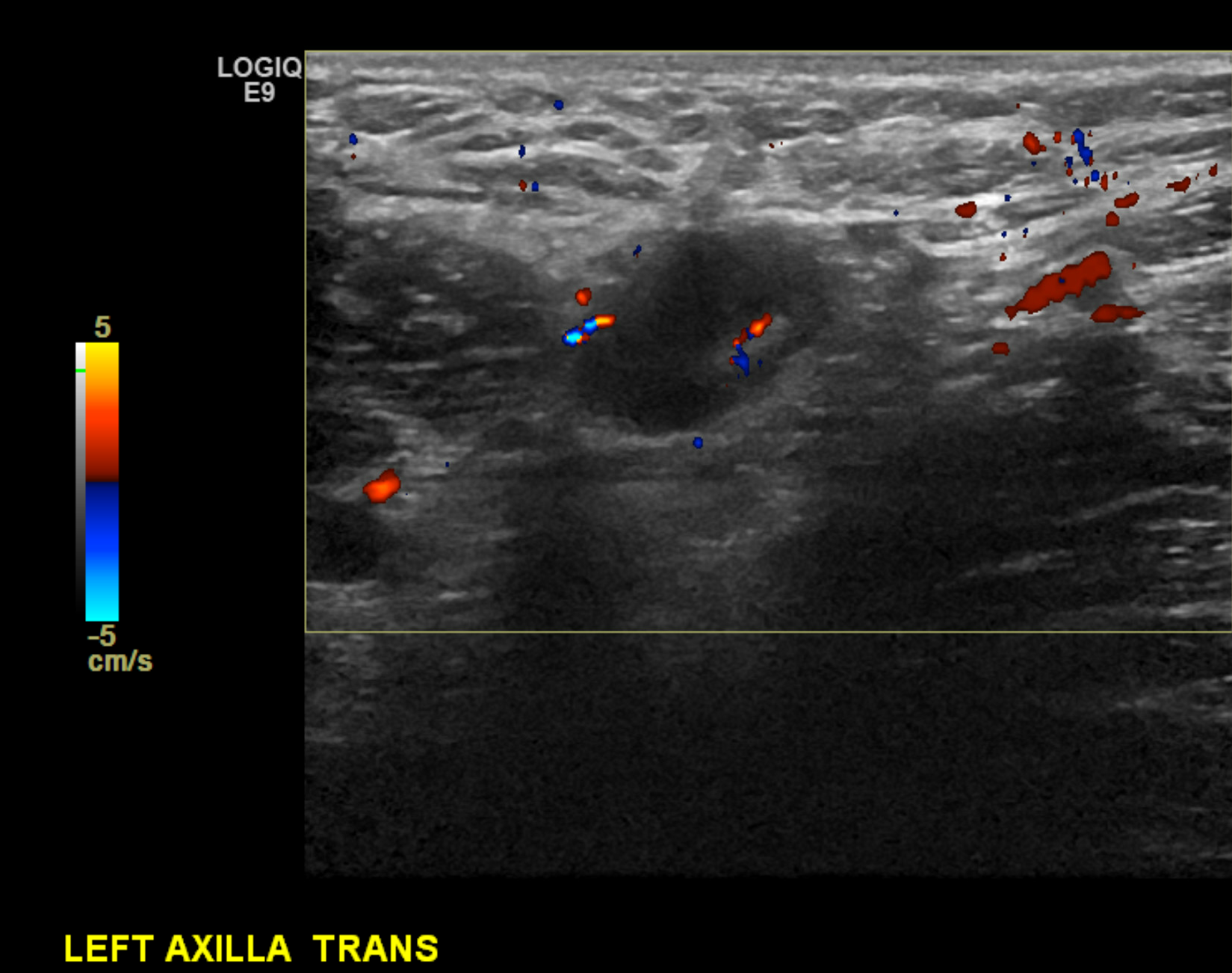

The axilla's anatomy is important in evaluating nodal disease and biopsy planning. The axilla contains lymph nodes and the axillary artery and vein. Normal lymph nodes demonstrate an echogenic fatty hilum, with hypoechoic cortices measuring less than 3 mm (see Images. Right Axillary Biopsy Proven Malignant Lymph Node with Cortical Thickening of 6 mm and Biopsy Proven Malignant Left Axillary Lymph Node with Cortical Thickening of 5 mm).

The axillary and subclavian arteries supply blood to the breast via the internal mammary (internal thoracic), lateral thoracic, and thoracoacromial artery branches. Most lymphatic drainage empties into the ipsilateral axillary nodal basin, while the internal mammary chain provides a small percentage of the drainage. As a rule of thumb, the ipsilateral axillary nodes provide 90% of the lymphatic drainage and 10% to the internal mammary chain. Contralateral breast drainage after a surgical course, such as in the setting of a mastectomy, is an uncommon but well-described phenomenon.[5]

Indications

Common indications for breast ultrasound include the following: [6]

- Palpable lump during clinical breast evaluation

- Axillary lymphadenopathy present on mammogram imaging

- Women younger than 40 years with the clinical presentation of certain anomalies

- Pregnant or lactating women

- Suspicious abnormality identified on mammogram imaging

- Nipple discharge

- Skin retraction or inversion of the nipple

- Surgical scarring evident on mammogram imaging

- Gynecomastia

- Suspicion of ruptured breast implants used to differentiate between intra- and extra-capsular ruptures

- Needle-guided percutaneous breast biopsy

- Follow-up of patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy

Contraindications

The use of breast ultrasound as a sole screening tool is inappropriate.[7]

Equipment

High-frequency ultrasound has improved over the past decade with standard linear frequency probes ranging from 7.5 MHz to 23 MHz, with high-density or single crystal probe components, which improves lateral resolution. Tissue harmonic imaging (THI) is also a standard feature of most entry-level ultrasound units for reducing reverberation and near-field artifacts. Real-time compound scanning aids in improved contrast resolution. Overall, a linear array transducer with a center frequency of at least 10 MHz is recommended by the ACR, with higher frequency transducers best utilized for high-resolution images and lower frequency utilized for deep tissue penetration and in patients with large breasts. A high-resolution, real-time, linear-array, broad-bandwidth transducer operating at a center frequency of a minimum of 12 MHz, preferably higher, should be used for breast ultrasounds.

An appropriate field of view should be obtained during the sonographic assessment of the breast. Panoramic imaging provides an increased longitudinal imaging perspective of breast lesions in relation to the surrounding breast tissue and can be employed in larger lesions or the setting of multiple lesions. Additional techniques include image splicing for large lesions and volumetric acquisitions, enabling 3D image generation.

The latest technology from ultrasound vendors now also boasts stand-alone linear frequency probes connecting wirelessly to mobile imaging application software.[8]

Most ultrasound software allows computer-aided detection (CAD) to assist in segmenting and identifying suspicious mass lesions. This technology allows for increased improvement in diagnostic proficiency.

Proper technical consideration is required to produce quality ultrasound images, such as the depth of the focal zone, time gain compensation measures, and overall gain used during mass lesion assessment.[9] The focal zone should be placed within the anterior third or middle third of the region between the chest wall and the skin. Regarding the gray-scale setting, the subcutaneous fat lobules should appear medium gray as opposed to hypoechoic or anechoic. Setting the gain to be high can make some cysts appear solid. Compound imaging used by averaging multiple ultrasound images can be utilized to improve the resolution and assessment of lesion margins.

Personnel

Breast ultrasound is performed by an ultrasound technician, radiologist, or a referring clinician with adequate technical and clinical competency for ultrasound evaluation.

Preparation

Breast ultrasound is a noninvasive procedure with none or very little special preparation required. Jewelry in the anatomical region of interest should be removed, and the patient is encouraged to wear loose clothing and undress the upper half of the torso before the examination.[10]

Technique or Treatment

Initial breast imaging of the patient should include a full clinical breast self-examination (BSE) to assess and validate all palpable masses identified by the patient or physician. Following BSE, a bilateral breast ultrasound is performed sequentially, sweeping the breast surface.

The breast is assessed in the 4 main quadrants: outer upper, outer inner, lower outer, and lower inner quadrants. Any lesions identified during the examination should be marked as a breast 'o clock position for future follow-up sessions.

The most common imaging technique is radial, star-shaped, or superior to inferior sweep of the entire breast, extending to the axillary space, parasternal, and clavicular surfaces.

The retroareolar space should also be evaluated systematically; the dense tissue causes posterior acoustic shadowing, limiting visibility posterior to its surface. This anatomical limitation can be overcome by either angling the probe upwards towards the retroareolar ducts or using a gel standoff pad with a decreased focal zone and altering the tissue gain compensation controls, visualizing the soft tissue posterior to the dense nipple tissue.[11]

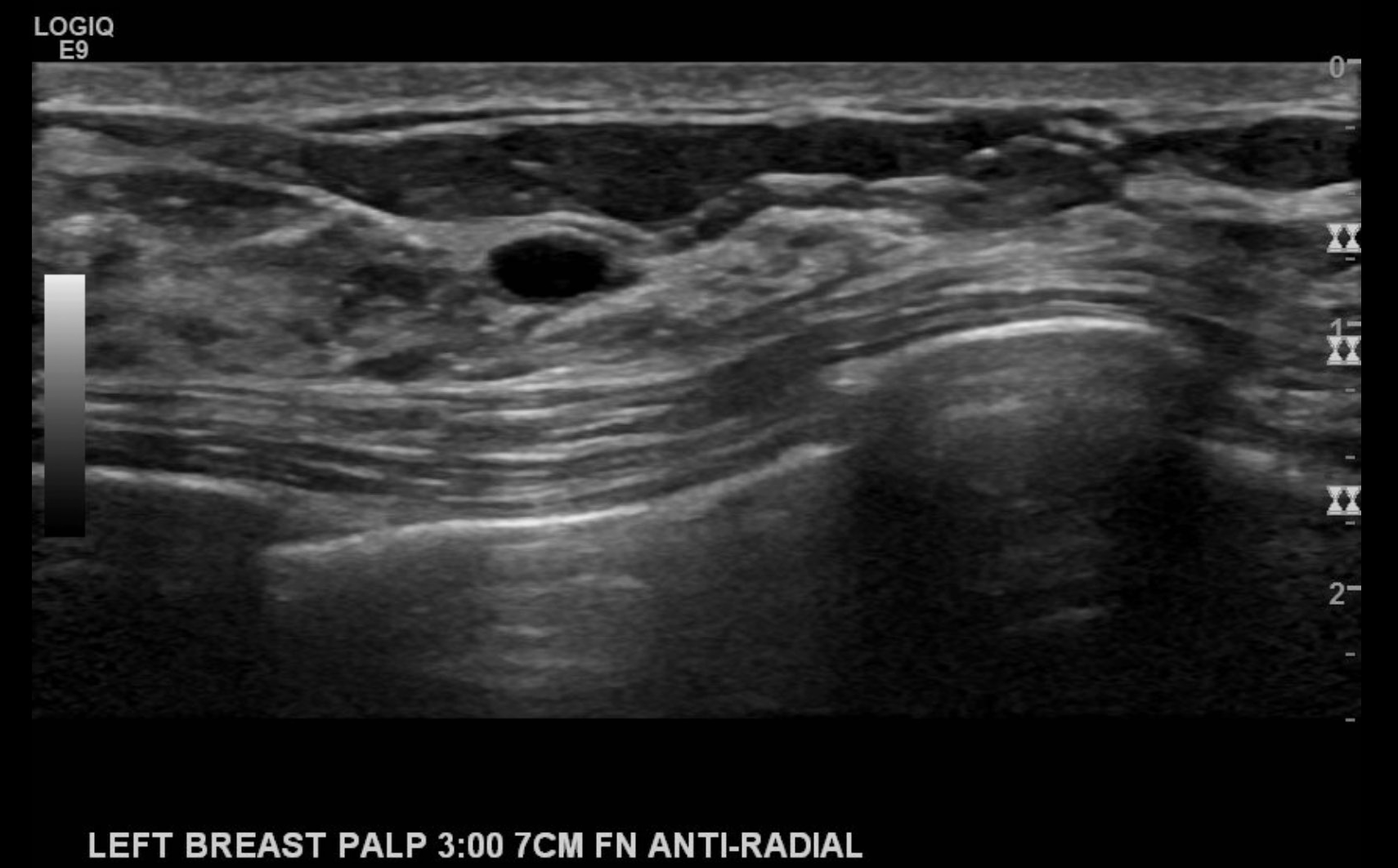

When measuring a lesion, the longest axis of a lesion should be measured, and units should be recorded to the nearest millimeter or centimeter. Three measurements of a lesion should be given, with the largest measurement representing the longest axis of the interrogated lesion. The second measurement should include a measurement perpendicular to the longest axis, and the third measurement should be obtained in an orthogonal view to the first 2, representing a different plane of the lesion in question.

Breasts vary in their fat and fibroglandular tissue composition. The categories based on tissue composition include:

- Homogenous background echotexture - fat

- Fat comprises the majority of breast tissue in this category

- Homogenous background echotexture - fibroglandular

- Consists of echogenic fibroglandular parenchyma beneath normal fat

- Heterogenous background echotexture

- Consists of varying degrees of echogenicity, which can obscure lesions

When assessing masses, the following descriptors need to be incorporated in the reporting and final assessment of a lesion:

- Shape: oval, round or irregular

- Oriental: parallel or not parallel

- Margin: circumscribed or not circumscribed (further characterized as indistinct, angular, microlobulated, or spiculated)

- Echo pattern: anechoic, hyperechoic, complex cystic and solid, hypoechoic, isoechoic, heterogenous

- Posterior features: No posterior features (see Image. Findings Demonstrating an Oval, Parallel, Circumscribed, Hypoechoic Mass with No Discernable Posterior Features), enhancement, shadowing (see Image. Biopsy Proven Atypical Ductal Hyperplasia), combined pattern(mixed enhancement and shadowing)

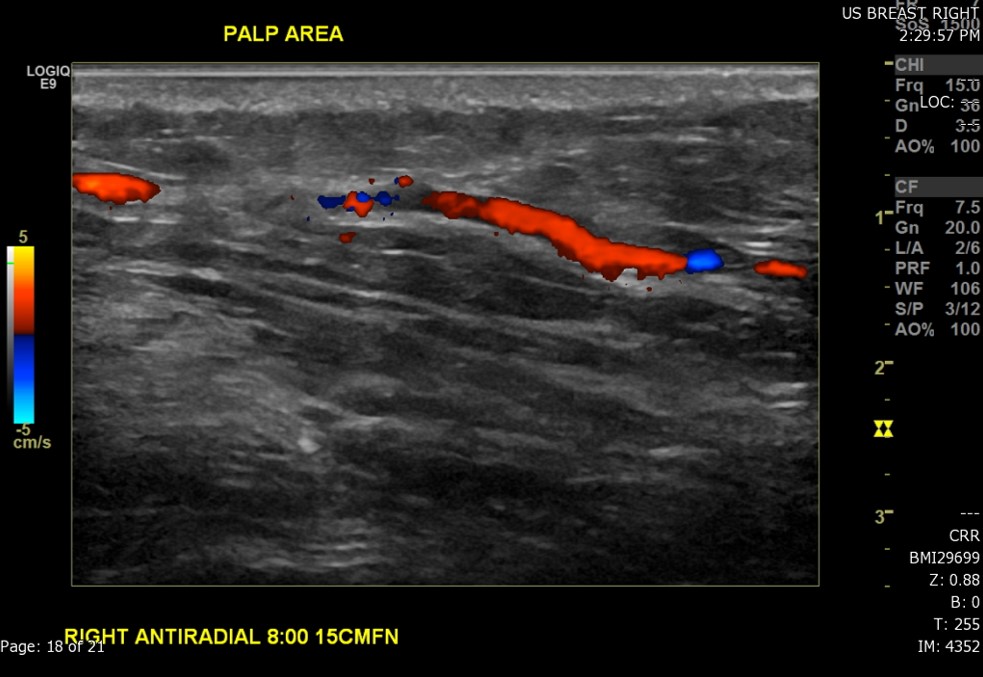

If calcifications are present, their location should be described to include whether they are located in a mass, outside a mass, or intraductal. Associated features of sonographic findings should also be evaluated for including architectural distortion, skin thickening or retraction, absence or presence of vascularity (rim or internal), changes of the associated ducts, and if applicable, assessment of elasticity as soft, intermediate, or hard. Certain findings have a pathognomonic appearance, including simple cysts (see Image. Simple Cyst of the Left Breast), clustered microcysts, complicated cysts, masses associated with the skin (in or on the skin), foreign bodies, lymph nodes, and vascular abnormalities such as Mondor disease, and arteriovenous malformations. Based on clinical history, seromas, and fat necrosis can also be confidently assessed on ultrasound.

Complications

Breast ultrasound is a safe, non-invasive procedure without any complications of the procedure itself.

Clinical Significance

Ultrasound as part of follow-up imaging for masses reported as breast imaging reporting and data system (BI-RADS) 2 or 3 (probably benign) has shown great value in assessing morphological changes to the sonographic appearance.

Using ultrasound as a standard follow-up imaging tool can promote the recharacterization of lesions during initial imaging assessment.

A complete ultrasound examination requires recording results in a standard breast report, including the patient's indications, findings, and results with differential diagnoses.

Any lesions noted during the examination should be measured in both transverse and longitudinal planes. The location, measurement, and echogenicity of all masses should be described as either hypoechoic, hyperechoic, or heterogeneous.

The various mass descriptors are used according to the ultrasound breast imaging and reporting system (US BIRADS) lexicon, which includes 6 main morphological descriptors for breast masses: [12]

The most common morphologic features associated with benign sonographic findings are: [13]

- Smooth and well-circumscribed margins

- Hyperechoic, isoechoic, or mildly hypoechoic in echogenicity

- Thin echogenic capsule or well-defined capsule border

- Ellipsoid shape, wider than tall appearance

- Macrolobulated; less than 3 lobulated margins

- Posterior acoustic enhancement

The most common morphologic features associated with malignant findings are as follows:

- Hypoechoic mass, on occasion, hyperechoic in appearance (see Image. Ultrasound Image of a Right Breast Mass)

- Spiculated margins

- Ill-defined borders, architectural distortion of surrounding soft tissue

- Posterior acoustic shadowing

- Taller than wide appearance

- Microcalcifications present [14]

Clinically significant fibroglandular tissue in males typically presents as a palpable "flame-shaped" focal area of fibroglandular tissue that is retroareolar in location. Hormonal effects of certain medications, including illicit drug use, often stimulate the growth of the otherwise rudimentary breast tissue in males (see Image. Left Breast Palpable Abnormality in a Male Representative of Gynecomastia).

When reporting a breast ultrasound, pertinent components should be included in the report as follows:

- Indication for the study

- Comparison to previous studies when applicable

- The technique used during the exam (to include the scope of interrogated tissue, positioning of the patient if notable to lesion identification, use of Doppler imaging, and use of 3D imaging if applicable) (see Image. Ultrasound Image of the Patient's Area of Palpable Concern in the Right Breast Demonstrates a Superficial Vein with a Focal Area of Absent Intraluminal Flow on Doppler Interrogation)

- A brief description of breast composition

- Appropriate description of a finding to include sonographic features, size, and location

- BI-RADS assessment (0 or 1 to 6)

- Management/recommendations regarding the need for follow-up, biopsy, or other clinical management decisions

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

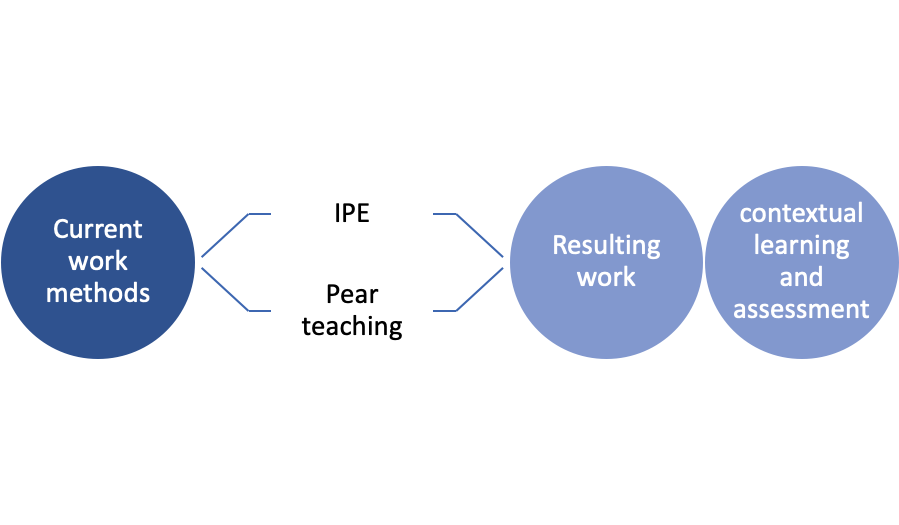

Healthcare professionals, including physicians, advanced care practitioners, nurses, pharmacists, and others, should possess advanced skills in interpreting breast ultrasound findings, recognizing nuances in imaging, and applying the latest techniques. This involves ongoing education to stay abreast of technological advancements and evolving guidelines, ensuring accurate assessments. As part of interprofessional education (IPE), point of care ultrasound (POCUS) has been expanding over many medical specialties.

Effective communication is fundamental. Professionals must engage in open dialogue, sharing insights, findings, and concerns to facilitate a cohesive team approach. Health professionals must also collaborate to create integrated care pathways, ensuring that patients move smoothly through the continuum of breast health, from screening to diagnosis and, if necessary, treatment. For full interprofessional collaboration, role clarification of each practitioner should be assessed. Conflict resolution methods between learner and practitioner should be provided for the best outcomes.

Collaborative strategic planning is crucial to align breast ultrasound practices across disciplines. Developing standardized protocols, updating guidelines, and incorporating evidence-based strategies collectively contribute to a cohesive and efficient approach to breast disease evaluation. Healthcare professionals can collectively enhance patient-centered care, improve outcomes, ensure patient safety, and optimize team performance in breast ultrasound.

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Monitoring

Pre-workshop assessments should include demographics as well as the attitudes of healthcare professionals regarding the use of IPE (see Image. Interprofessional Education in Breast Ultrasound). During training and collaborative teaching events, simulation of activities can promote increased awareness and interest in ultrasound imaging. Following workshop integration, a follow-up regarding attitudes of IPE should be encouraged to assess if the resulting work leads to contextual learning and assessment across all fields of medicine.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Esmaeili M, Ayyoubzadeh SM, Ahmadinejad N, Ghazisaeedi M, Nahvijou A, Maghooli K. A decision support system for mammography reports interpretation. Health information science and systems. 2020 Dec:8(1):17. doi: 10.1007/s13755-020-00109-5. Epub 2020 Apr 1 [PubMed PMID: 32257128]

Berg WA. Reducing Unnecessary Biopsy and Follow-up of Benign Cystic Breast Lesions. Radiology. 2020 Apr:295(1):52-53. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200037. Epub 2020 Feb 18 [PubMed PMID: 32073379]

Toyoda Y, Oh EJ, Premaratne ID, Chiuzan C, Rohde CH. Affordable Care Act State-Specific Medicaid Expansion: Impact on Health Insurance Coverage and Breast Cancer Screening Rates. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2020 Mar 3:():. pii: S1072-7515(20)30213-1. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2020.01.031. Epub 2020 Mar 3 [PubMed PMID: 32272206]

Gokhale S. Ultrasound characterization of breast masses. The Indian journal of radiology & imaging. 2009 Jul-Sep:19(3):242-7. doi: 10.4103/0971-3026.54878. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19881096]

Wellner R, Dave J, Kim U, Menes TS. Altered lymphatic drainage after breast-conserving surgery and axillary node dissection: local recurrence with contralateral intramammary nodal metastases. Clinical breast cancer. 2007 Feb:7(6):486-8 [PubMed PMID: 17386126]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMendelson EB, Berg WA, Gordon PB. Benefits of Supplemental Ultrasonography With Mammography. JAMA internal medicine. 2019 Aug 1:179(8):1150. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2379. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31380949]

Evans A, Trimboli RM, Athanasiou A, Balleyguier C, Baltzer PA, Bick U, Camps Herrero J, Clauser P, Colin C, Cornford E, Fallenberg EM, Fuchsjaeger MH, Gilbert FJ, Helbich TH, Kinkel K, Heywang-Köbrunner SH, Kuhl CK, Mann RM, Martincich L, Panizza P, Pediconi F, Pijnappel RM, Pinker K, Zackrisson S, Forrai G, Sardanelli F, European Society of Breast Imaging (EUSOBI) , with language review by Europa Donna–The European Breast Cancer Coalition. Breast ultrasound: recommendations for information to women and referring physicians by the European Society of Breast Imaging. Insights into imaging. 2018 Aug:9(4):449-461. doi: 10.1007/s13244-018-0636-z. Epub 2018 Aug 9 [PubMed PMID: 30094592]

Prentašic P, Heisler M, Mammo Z, Lee S, Merkur A, Navajas E, Beg MF, Šarunic M, Loncaric S. Segmentation of the foveal microvasculature using deep learning networks. Journal of biomedical optics. 2016 Jul 1:21(7):75008. doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.21.7.075008. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27401936]

Bick U, Trimboli RM, Athanasiou A, Balleyguier C, Baltzer PAT, Bernathova M, Borbély K, Brkljacic B, Carbonaro LA, Clauser P, Cassano E, Colin C, Esen G, Evans A, Fallenberg EM, Fuchsjaeger MH, Gilbert FJ, Helbich TH, Heywang-Köbrunner SH, Herranz M, Kinkel K, Kilburn-Toppin F, Kuhl CK, Lesaru M, Lobbes MBI, Mann RM, Martincich L, Panizza P, Pediconi F, Pijnappel RM, Pinker K, Schiaffino S, Sella T, Thomassin-Naggara I, Tardivon A, Ongeval CV, Wallis MG, Zackrisson S, Forrai G, Herrero JC, Sardanelli F, European Society of Breast Imaging (EUSOBI), with language review by Europa Donna–The European Breast Cancer Coalition. Image-guided breast biopsy and localisation: recommendations for information to women and referring physicians by the European Society of Breast Imaging. Insights into imaging. 2020 Feb 5:11(1):12. doi: 10.1186/s13244-019-0803-x. Epub 2020 Feb 5 [PubMed PMID: 32025985]

Kaminsky O, Abdul Halim N, Zilbermints V, Sharon E, Aranovich D. Young Woman in the Breast Clinic: Ultrasound or Not? The Israel Medical Association journal : IMAJ. 2019 Sep:21(9):612-614 [PubMed PMID: 31542907]

Pushkin J, Berg WA. Differences in Breast Density Awareness, Knowledge, and Plans. Journal of general internal medicine. 2020 Aug:35(8):2472. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-05804-3. Epub 2020 Mar 27 [PubMed PMID: 32221857]

Tutar B, Esen Icten G, Guldogan N, Kara H, Arıkan AE, Tutar O, Uras C. Comparison of automated versus hand-held breast US in supplemental screening in asymptomatic women with dense breasts: is there a difference regarding woman preference, lesion detection and lesion characterization? Archives of gynecology and obstetrics. 2020 May:301(5):1257-1265. doi: 10.1007/s00404-020-05501-w. Epub 2020 Mar 25 [PubMed PMID: 32215718]

Flory V, Lévy G, Viotti J, Schiappa R, Elkind L, Ghez C, Pellegrin A, Occelli A, Dejode M, Delpech Y, Fouché Y, Figl A, Machiavello JC, Haudebourg J, Peyrottes I, Chapellier C, Barranger E. [Preoperative breast imaging review: Interests and limits of specialized validation in oncology]. Bulletin du cancer. 2020 Mar:107(3):295-307. doi: 10.1016/j.bulcan.2019.11.013. Epub 2020 Feb 27 [PubMed PMID: 32115178]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceVincent-Salomon A, Bataillon G, Djerroudi L. [Hereditary breast carcinomas pathologist's perspective]. Annales de pathologie. 2020 Apr:40(2):78-84. doi: 10.1016/j.annpat.2020.02.023. Epub 2020 Mar 30 [PubMed PMID: 32241645]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence