Introduction

The human body is made of a complex system of ascending and descending pathways that permit communication between the brain and spinal cord. There are also pathways connecting different areas of the brain. These pathways are called white matter tracts in the central nervous system (CNS). These are all nerve fibers covered with myelin sheaths which are derived from oligodendrocytes. The corticospinal tract belongs to one of the most important descending tracts of the CNS. It contains fibers from the upper motor neurons to synapse on the lower motor neurons. Upper motor neurons (UMN) can be described as the nerve fibers responsible for the communication between the brain to the spinal cord. Lower motor neurons (LMN) are the nerve fibers responsible for the communication between the spinal cord to muscle.

Although damage to both UMN and LMN result in muscle weakness, damage to upper motor neurons may result in increased reflexes, increased tone, positive Babinski, and spastic paresis. On the other hand, damage to lower motor neurons is usually accompanied by muscle atrophy, fasciculations, and flaccid paralysis.

Descending tracts are responsible for relaying information from cortical regions to the periphery to initiate and modulate movement. The corticospinal tract is the largest descending tract present in humans and is divided into anterior and lateral components. The lateral corticospinal tract sends fibers predominantly to the extremity muscles, and the cortical innervation is contralateral, in other words, the left motor cortex controls the right extremities. The anterior corticospinal tract sends fibers mainly to the trunk or axial muscles. The control is both ipsilateral and contralateral. Therefore, trunk muscles are generally bilaterally cortically innervated.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

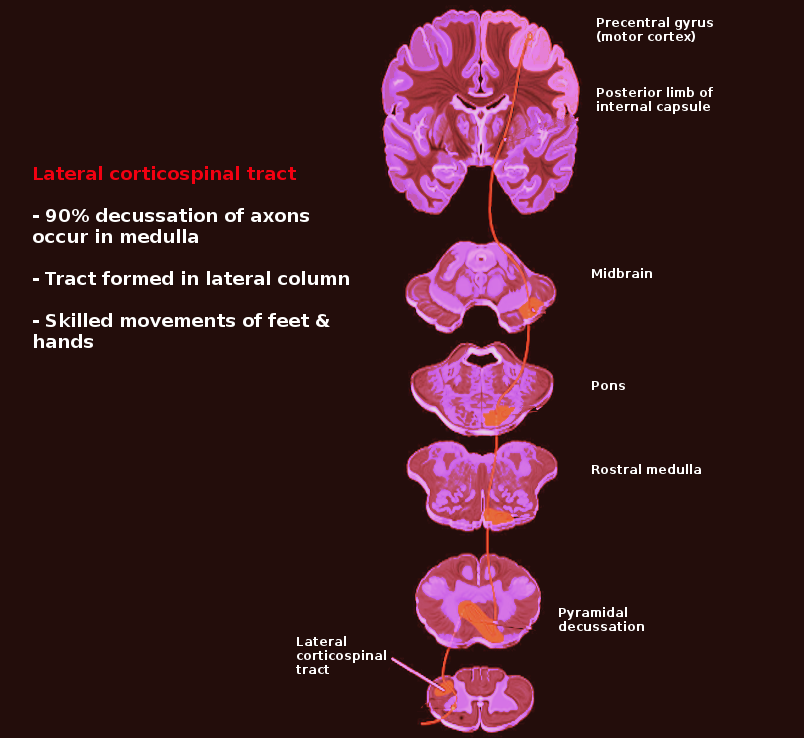

The lateral corticospinal tract contains over 90% of the fibers present in the corticospinal tract and runs the length of the spinal cord. The primary responsibility of the lateral corticospinal tract is to control the voluntary movement of contralateral limbs.[1] The origination of the Lateral corticospinal tract is in the primary motor cortex which lies in the precentral gyrus. When a stimulus is engaged, the cell body of the lateral corticospinal tract (in the primary motor cortex, the upper motor neuron) will send an impulse through the tract that will eventually travel to the anterior horn of the spinal cord from where it will transmit the impulse via lower motor neurons into the muscle fibers. This pathway can be scrutinized into greater detail.

When a motor act is planned and initiated by the premotor and supplemental motor cortex to the primary motor cortex in the precentral gyrus to move the leg, an impulse generated from the primary motor cortex will be conducted through the lateral corticospinal tract ipsilaterally through the corona radiata. It passes through the posterior limb of the internal capsule, through the cerebral peduncle and basis pontis, decussates at the caudal medulla (pyramidal decussation), and then continues to descend contralaterally into the spinal cord. Once that impulse reaches the cell body in the anterior horn (lower motor neuron) of the spinal cord, the motor fibers from the lower motor neurons will leave the spinal cord, proceed through the spinal nerve root, plexus, peripheral nerve, and finally to the neuromuscular junction where the impulse is transmitted to the muscle fibers resulting in contraction of that limb muscles. Damage to any of these structures may cause motor deficits.

Due to the pyramidal decussation of the lateral corticospinal tract in the caudal medulla, damage rostral or caudal to this decussation will be the defining feature of whether there will be ipsilateral or contralateral deficits. For example, if there is a lesion in the precentral gyrus of the left cerebral cortex, the patient will exhibit upper motor neuron signs with damage to the right side of the body. Contrarily, if there is spinal cord damage on the left side (below the pyramidal decussation), motor deficits will be present on the left side of the body. If there is spinal cord damage at the level of the anterior horn, then lower motor neuron signs will be present with ipsilateral deficits.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The lateral corticospinal tract is a very long structure. Damage to various vasculature may result in damage to the tract, depending on its location.

The primary motor cortex for the face and upper extremity receives its arterial supply from the middle cerebral artery (MCA). The primary motor cortex for the lower extremity receives its supply from the anterior cerebral artery (ACA). Damage to the lateral corticospinal tract here would result in contralateral motor deficits with UMN signs. An MCA occlusive lesion (stroke) will cause predominant face and arm weakness while an ACA occlusion will lead to lower extremity weakness. The corona radiata and internal capsule are supplied by the lenticulostriate arteries (branches of MCA). Occlusion of a lenticulostriate artery causing an ischemic infarction of the internal capsule (a lacunar infarct) will cause contralateral weakness of both the face, arm, and leg.[2] The lateral corticospinal tract through the brainstem except the caudal medulla is supplied mainly by the paramedian branches of the basilar artery. The caudal medulla receives vascular supply to its midline structures via the anterior spinal artery. The anterior spinal artery continues to run down the spinal cord, and damage to this artery may result in motor deficits related to the corticospinal tract.

Surgical Considerations

The lateral corticospinal tract is almost always avoided by neurosurgeons during surgery. Newer modalities like tractography and electrophysiological monitoring help them to achieve good resection of tumors by avoiding the tract and to prevent the development of irreversible motor deficits in the patients.

Clinical Significance

The lateral corticospinal tract is affected by a variety of pathologies. This includes strokes, poliomyelitis, spinal muscular atrophy, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, vitamin B12 deficiency, Friedreich ataxia, and Brown-Sequard syndrome.

Stroke

Any ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke affecting an area of the brain that contains the lateral corticospinal tract will cause contralateral weakness of the extremities. When the language area of the dominant hemisphere is involved, the patient will present with aphasia. When the orolingual regions of the cortex are involved, the patient will present with dysarthria. Hemiparesis and aphasia are important disabilities that are often persistent after a stroke, and it is the leading reason for stroke-related disability. Stroke is now the fifth leading cause of death in the United States and the leading cause of disability.

Damage of the upper motor neurons in the cerebral cortex leads to secondary axonal loss affecting the lateral corticospinal tract (Wallerian degeneration). Wallerian degeneration of the corticospinal tract can often be visualized in computed tomogram (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain (see below).

Poliomyelitis

Although almost completely eradicated, poliomyelitis was a prevalent demonstration of damage to the lateral corticospinal tract. Poliovirus is a member of the Picornaviridae family and has a fecal-oral transmission. Once transmitted, it replicates in the oropharynx and small intestine before spreading via the bloodstream to the CNS. In the CNS poliovirus causes the destruction of the cell bodies in the anterior horn of the spinal cord.[3] This results in ipsilateral LMN deficits such as muscle weakness/atrophy, fasciculations, hyporeflexia, and flaccid paralysis. Manifestations of this infection will begin in the legs and ascend until it reaches the respiratory muscles which would cause paralysis and death. Being a viral disease, the CSF will show lymphocytic pleocytosis (increased white blood cells [WBCs]), a slight increase in protein, and no change in glucose. Thanks to the inactivated polio vaccine, this deathly illness is no longer prevalent. In the United States, the commoner form of polio-like illness with similar pathophysiology is caused by other enteroviruses. The epidemics of acute flaccid myelitis caused by different strains of enteroviruses share the same pathophysiology.

Spinal Muscular Atrophy

Spinal muscular atrophy, also known as Werdnig-Hoffman disease in infants and Kugelberg-Welander disease in juveniles, is a congenital degeneration of the anterior horns of the spinal cord. Since this disease results in symmetric degeneration of the anterior horns, it results in symmetric weakness with lower motor neuron signs. Infants are characteristically described as "floppy babies" with associated tongue fasciculations. This disease carries an autosomal recessive inheritance with a mutation in the SMN1 gene.[4]

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

There is a renewed awareness of ALS due to the 2014 social media "ice bucket challenge." Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) can be caused by a defect in superoxide dismutase 1. Commonly known as Lou Gehrig disease, it displays both UMN and LMN deficits. Upper motor neuron deficits may include, dysphagia, dysarthria, spastic gait, and clonus. As a result of damage to the anterior horn of the spinal cord, lower motor neuron signs include weakness (dysphagia), fasciculations, and muscle atrophy. Patients experience such severe dysphagia that a common cause of death is aspiration pneumonia. This disease is classically associated with Stephen Hawking. Riluzole is a pharmaceutical treatment utilized for this condition.[5]

Vitamin B12 Deficiency

Deficiency of vitamin B12 most commonly occurs due to malabsorption (Chron's disease, gastric bypass surgery), malnutrition (vegans), pernicious anemia, or rarely due to Diphyllobothrium latum (fish tapeworm). Most commonly, it occurs due to malabsorption rather than malnutrition because the human liver has stores of vitamin B12 that may last up to 3 to 5 years. Malabsorption versus malnutrition has historically been distinguished via the Schilling test. Diagnosis of B12 deficiency may be done by labs illustrating an increase in both methylmalonic acid and homocysteine. As homocysteine is also elevated in folate deficiency, it is important to test for methylmalonic acid levels to distinguish the 2. Neurologic manifestations of this condition cause subacute combined degeneration of the cord.[6] The term describes a combined degeneration of the dorsal column and the lateral (corticospinal) tract. There is widespread demyelination of the spinocerebellar tracts, lateral corticospinal tracts, and the dorsal columns. The patient may experience symptoms such as paresthesias, ataxic gait (spinocerebellar), impaired proprioception (dorsal columns), and UMN motor weakness since the anterior horn is generally spared.

Friedreich Ataxia

An autosomal recessive trinucleotide repeat disorder, Friedreich ataxia is due to a GAA repeat on chromosome 9 resulting in a defect in the frataxin gene (iron-binding protein). Defects in the frataxin gene cause impairment in mitochondria.[7] Neurologic manifestations of this disease include degeneration of the lateral corticospinal tract (spastic paralysis), spinocerebellar tract (gait ataxia), dorsal columns (impaired proprioception), and dorsal root ganglia (loss of deep tendon reflexes). Young children often present with kyphoscoliosis and may have associated staggering gait, nystagmus, pes cavus, dysarthria, hammertoes, diabetes mellitus, and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (COD).

Brown-Sequard Syndrome

Brown-Sequard syndrome is due to a hemisection of the spinal cord. A perfect example of a variety of co-existing deficiencies, it is worth mentioning due to the encompassing involvement of the lateral corticospinal tract. Patients symptoms may include:

- Ipsilateral LMN signs (flaccid paralysis/fasciculations) at the level of the lesion due to damage of lateral corticospinal tracts

- Ipsilateral UMN signs below the level of the lesion (spastic paralysis) due to lateral corticospinal tract damage

- Ipsilateral loss of ALL sensation at the level of the lesion

- Ipsilateral loss of proprioception and vibration below the lesion due to dorsal column damage

- Contralateral loss of pain and temperature below the lesion due to damage to the spinothalamic tract

Clinicians should note that if the lesion occurs above T1, the patient may present with Horner syndrome (miosis, ptosis, and anhidrosis) due to damage to the sympathetic chain.[8]

Media

References

Kraskov A, Baker S, Soteropoulos D, Kirkwood P, Lemon R. The Corticospinal Discrepancy: Where are all the Slow Pyramidal Tract Neurons? Cerebral cortex (New York, N.Y. : 1991). 2019 Aug 14:29(9):3977-3981. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhy278. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30365013]

Sato S, Dan M, Hata H, Miyasaka K, Hanihara M, Shibahara I, Inoue Y, Kumabe T. Safe Stereotactic Biopsy for Basal Ganglia Lesions: Avoiding Injury to the Basal Perforating Arteries. Stereotactic and functional neurosurgery. 2018:96(4):244-248. doi: 10.1159/000492057. Epub 2018 Aug 28 [PubMed PMID: 30153687]

Fishman PS. Late-convalescent poliomyelitis. Corticospinal tract integrity. Archives of neurology. 1987 Jan:44(1):98-100 [PubMed PMID: 3800728]

Walter MC, Stauber AJ. [Spinal muscular atrophy - clinical spectrum and therapy]. Fortschritte der Neurologie-Psychiatrie. 2018 Sep:86(9):543-550. doi: 10.1055/a-0621-9139. Epub 2018 Sep 24 [PubMed PMID: 30248687]

Bissaro M, Federico S, Salmaso V, Sturlese M, Spalluto G, Moro S. Targeting Protein Kinase CK1δ with Riluzole: Could It Be One of the Possible Missing Bricks to Interpret Its Effect in the Treatment of ALS from a Molecular Point of View? ChemMedChem. 2018 Dec 20:13(24):2601-2605. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201800632. Epub 2018 Nov 21 [PubMed PMID: 30359484]

Natera-Villalba E, Estévez-Fraga C, Sánchez-Herrera FA, Ruiz-Gómez F, Sanz BZ, Cánovas AA, Martínez-Castrillo JC, Corral ÍC. Simultaneous acute presentation of generalized chorea and subacute combined degeneration secondary to vitamin B12 deficiency. Parkinsonism & related disorders. 2018 Oct:55():2-4. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2018.09.006. Epub 2018 Sep 8 [PubMed PMID: 30220555]

Rota S, Marchina E, Todeschini A, Nanetti L, Rinaldi F, Vanotti A, Mariotti C, Padovani A, Filosto M. Very late-onset friedreich ataxia with laryngeal dystonia. Case reports in neurology. 2014 Sep-Dec:6(3):287-90. doi: 10.1159/000370062. Epub 2014 Dec 12 [PubMed PMID: 25685137]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceZeng Y, Ren H, Wan J, Lu J, Zhong F, Deng S. Cervical disc herniation causing Brown-Sequard syndrome: Case report and review of literature (CARE-compliant). Medicine. 2018 Sep:97(37):e12377. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000012377. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30213001]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence