Introduction

"Adam’s Apple" is the colloquial term used to describe what is formally termed the laryngeal prominence of the thyroid cartilage. The colloquial name is thought to come from a reference to the forbidden fruit being stuck in Adam’s throat or perhaps a mistranslation of the Hebrew term for the structure described as “the swelling of a man.”[1] It is sometimes called a goozle in parts of the American South, playing on the verb "to guzzle."

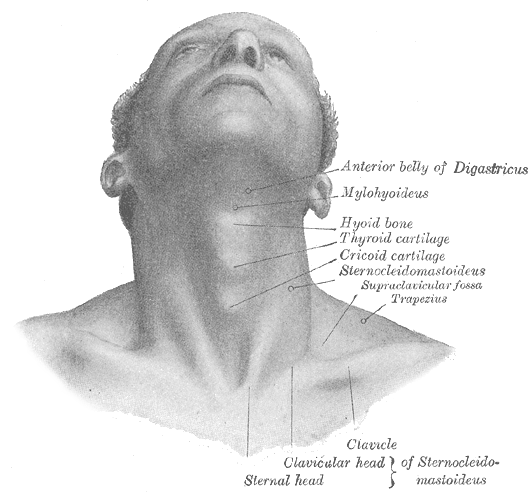

The laryngeal prominence of the thyroid cartilage is one of the most significant external landmarks in the neck and is very useful for anatomical orientation in procedures such as cricothyroidotomy. It is notably more prominent in males than females, increasing in prominence as a secondary male sex characteristic in puberty, and primarily acts to protect the vocal cords posteriorly. The true vocal folds insert (via the vocal ligament) into the laryngeal surface of the thyroid cartilage at the anterior keel, 1 to 2 cm inferior to the point of maximum projection of the thyroid cartilage. As the larynx enlarges in puberty, this anterior segment further enlarges in males, lengthening the true vocal folds and leading to a deeper voice.[2]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The thyroid cartilage is the largest of the nine cartilages of the larynx. The laryngeal prominence, the "Adam’s Apple," is the most exteriorly visible portion of this structure and is where the two halves of cartilage meet in the midline during embryological development. It has important historical, cultural, and interventional implications.

It is a secondary sexual characteristic: meaning it appears around puberty and helps distinguish between the sexes, as it is more prominent in males than in females, leading to the societal and cultural designation of the laryngeal prominence as a "male" secondary sex characteristic[3]. The increase of the laryngeal prominence occurs during puberty and is thought to play a role in the voice maturation that also occurs in this period. However, no work has been done to prove this relationship decisively, only small reports of cadaver studies.[4]

The classic measurement of the interlaminar angle (ILA) at the level of the vocal processes is 90 degrees in the male population and 120 degrees in females. The broader ILA in women causes the cartilage to protrude less, not push up against the skin of the neck, and ultimately be less visible. In both sexes, regardless of the angle, the primary function of the Adam’s Apple is the same as that of the thyroid cartilage it comprises, to protect the vocal cords immediately behind and inferior to it.

Embryology

As the thyroid cartilage is connective tissue, it is a derivative of the neural crest mesenchyme of the pharyngeal arch. As with the surrounding structures in the larynx, the thyroid cartilage is an embryological derivative of both the fourth and sixth pharyngeal arches.[5]

The thyroid cartilage grows in size throughout fetal maturation, descends, and becomes more cylindrical than funnel-shaped. The two laminae fuse anteriorly, except in the superior most portion, which forms the thyroid notch. The laryngeal prominence in childhood is equivalent in males and females, but the Adam’s Apple protrudes with a greater ILA and greater anterior angulation in males as puberty ensues. Male larynges grow larger under the influence of different hormone levels, principally due to an elevation in testosterone.[2] During puberty, calcification of the thyroid cartilage begins gradually and continues throughout puberty and into adulthood. Most adult male thyroid cartilages are heavily ossified by middle age.[4]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The area surrounding the thyroid cartilage is drained by the superior laryngeal vein superiorly, as it protrudes from the thyrohyoid membrane to join the superior thyroid vein, which empties into the internal jugular vein, coursing cephalad from the level of the cricothyroid membrane.[6]

The arterial supply originates from divisions of the external carotid artery, with the superior laryngeal artery coursing superiorly and the superior thyroid artery more inferiorly. The superior laryngeal artery divides from the superior thyroid artery soon after originating from the external carotid and before it courses inferiorly. The artery travels with the internal branch of the superior laryngeal nerve and pierces the thyrohyoid membrane.[7]

The lymphatic drainage of this area is provided by the superior deep cervical nodes (level II) and the pretracheal nodes (level VI) that further drain into the deep cervical lymphatic basins. The superior deep cervical chain runs underneath the sternocleidomastoid muscle along with the internal jugular vein and accessory nerve. On the left side, this merges with the thoracic duct and with the brachiocephalic vein (also occasionally with an accessory thoracic duct) on the right.

Nerves

The laryngeal prominence of the thyroid cartilage is a supportive, protective structure with no distinct, named innervation. However, its location sits between the internal and external branches of the superior laryngeal nerve, a branch of the vagus nerve (CN X). Superiorly, the internal branch pierces the thyrohyoid membrane to provide sensation to the laryngeal mucosa. Inferiorly, the external branch reaches to innervate the cricothyroid muscle.

Other important nerve structures in this region include the vagus nerve laterally, coursing down inferiorly in the carotid sheath. Also, the ansa cervicalis is located deeper and more laterally, innervating the overlying strap muscles.

Muscles

All along the superior portion of the thyroid cartilage, the thyrohyoid membrane connects the thyroid cartilage to the hyoid bone superiorly. The laryngeal prominence itself is directly attached to the hyoid by the median thyrohyoid ligament. The thyrohyoid muscle receives innervation from CN XII and C1 and works to depress the larynx.

The infrahyoid, or “strap” muscles (sternohyoid and sternothyroid muscles), depress the hyoid bone and course anteriorly to the thyroid cartilage. These muscles obtain their nerve supply from the bilateral ansa cervicalis.[8]

Surgical Considerations

Chondrolaryngoplasty, also known as a tracheal shave or a laryngeal shave, is a cosmetic outpatient procedure to reduce the visible prominence of the Adam’s Apple. It has an excellent prognosis and is generally performed by gender-confirmation surgeons for patients transitioning from male to female or who simply no longer desire a visible Adam’s Apple. In patients who have undergone gender affirmation surgery, chondrolaryngoplasty is occasionally performed in conjunction with a crico-thyroidopexy procedure that aims to raise the pitch of the patient’s voice.[9]

The ala, or laminae, of the thyroid cartilage also can provide donor tissue for cartilage grafts. It has been used in laryngotracheoplasty to repair pediatric tracheocutaneous fistulas and in laryngotracheal reconstruction in the pediatric population to treat subglottic stenosis.[10][11]

Clinical Significance

The Adam’s Apple is the most prominent and one of the most significant laryngeal structures visible exteriorly. Its location is important in many surgical and emergency procedures, especially in identifying the cricothyroid membrane for a cricothyroidotomy. Studies have shown this anatomical landmark is more difficult to palpate in females than in males in such emergencies, given the more pronounced angulation in males.[12] It is also more challenging to palpate in the obese neck.

Additionally, as the Adam’s Apple is a secondary sex characteristic, its appearance is a cosmetic consideration for some transgender patients and those exploring gender affirmation or reassignment surgery.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Sturm A, Chaiet SR. Chondrolaryngoplasty-Thyroid Cartilage Reduction. Facial plastic surgery clinics of North America. 2019 May:27(2):267-272. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2019.01.005. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30940393]

Zamponi V, Mazzilli R, Mazzilli F, Fantini M. Effect of sex hormones on human voice physiology: from childhood to senescence. Hormones (Athens, Greece). 2021 Dec:20(4):691-696. doi: 10.1007/s42000-021-00298-y. Epub 2021 May 28 [PubMed PMID: 34046877]

Hsu CY. [Transgender and Gender Dysphoria: Viewpoints on Clinical Care and Psychological Stress]. Hu li za zhi The journal of nursing. 2023 Feb:70(1):17-22. doi: 10.6224/JN.202302_70(1).04. Epub [PubMed PMID: 36647306]

Glikson E, Sagiv D, Eyal A, Wolf M, Primov-Fever A. The anatomical evolution of the thyroid cartilage from childhood to adulthood: A computed tomography evaluation. The Laryngoscope. 2017 Oct:127(10):E354-E358. doi: 10.1002/lary.26644. Epub 2017 Jun 13 [PubMed PMID: 28608401]

Lungova V, Thibeault SL. Mechanisms of larynx and vocal fold development and pathogenesis. Cellular and molecular life sciences : CMLS. 2020 Oct:77(19):3781-3795. doi: 10.1007/s00018-020-03506-x. Epub 2020 Apr 6 [PubMed PMID: 32253462]

Bunch PM, Hughes RT, White EP, Sachs JR, Frizzell BA, Lack CM. The Pharyngolaryngeal Venous Plexus: A Potential Pitfall in Surveillance Imaging of the Neck. AJNR. American journal of neuroradiology. 2021 May:42(5):938-944. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A7033. Epub 2021 Mar 4 [PubMed PMID: 33664114]

Shreevastava AK, Das RS, Maheshwari TP, Damodhar BK. Bilateral higher carotid termination with rare anomalous emergence of ventral branches of the external carotid arteries: A cadaver study. SAGE open medical case reports. 2022:10():2050313X221138659. doi: 10.1177/2050313X221138659. Epub 2022 Dec 10 [PubMed PMID: 36530368]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKent DT, Schwartz AR, Zealear D. Ultrasound Localization and Percutaneous Electrical Stimulation of the Hypoglossal Nerve and Ansa Cervicalis. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2021 Jan:164(1):219-225. doi: 10.1177/0194599820959275. Epub 2020 Oct 20 [PubMed PMID: 33076752]

Kreukels BPC, Köhler B, Nordenström A, Roehle R, Thyen U, Bouvattier C, de Vries ALC, Cohen-Kettenis PT, dsd-LIFE group. Gender Dysphoria and Gender Change in Disorders of Sex Development/Intersex Conditions: Results From the dsd-LIFE Study. The journal of sexual medicine. 2018 May:15(5):777-785. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2018.02.021. Epub 2018 Mar 30 [PubMed PMID: 29606626]

Cheng J, Jacobs I. Thyroid ala cartilage graft laryngotracheoplasty for closure of large pediatric tracheocutaneous fistula. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2013 Jan:77(1):147-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2012.09.033. Epub 2012 Oct 13 [PubMed PMID: 23073169]

Gaffey MM, Sun RW, Richter GT. A novel surgical treatment for posterior glottic stenosis using thyroid ala cartilage - A case report and literature review. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2018 Nov:114():129-133. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2018.07.025. Epub 2018 Aug 1 [PubMed PMID: 30262350]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSchouela N, Woo MY, Pan A, Cheung WJ, Perry JJ. Perceived versus actual cricothyroid membrane landmarking accuracy by emergency medicine residents and staff physicians. CJEM. 2020 Jul:22(4):523-527. doi: 10.1017/cem.2019.483. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32038001]