Introduction

Local flaps for soft tissue reconstruction are commonly divided into 4 types depending on the type of movement required to transfer the flap into the defect: advancement, rotation, transposition, and interpolation.[1][2][3] Advancement, rotation, and transposition involve tissue transfer immediately adjacent to the defect, whereas interpolation transfers tissue over or under intervening normal tissue to reach the defect.[4] For this reason, interpolated flaps are often considered to be "regional" flaps rather than "local" flaps, and more often than not, require a second-stage procedure to divide the bridge of flap tissue, the pedicle, that traverses the normal tissue between the flap donor site and the defect to be reconstructed (see Image. Interpolated Flaps). While the need for a second procedure may be a drawback to many interpolated flap reconstruction techniques, the main advantages of interpolated flaps are their reliable blood supply and their ability to transfer larger amounts of tissue than many other local flap options provide.

The "waltzing" or "walking" flaps were among the first interpolated flaps described. Early reconstructive surgeons, including Sir Harold Delf Gillies, Sir Archibald McIndoe, and Vladimir Filatov, popularized them during WWI and WWII. These flaps require multi-stage operations, as the flaps are initially transferred to an intermediate location before reaching the primary defect because the donor sites are too distant to permit defect coverage with the first stage. After 4 to 6 weeks, the pedicle is released from the donor site, and the intermediate inset site then acts as the base of the flap as the end of the flap that was initially connected to the donor site is then moved either into the defect or a new intermediate inset site closer to the defect.[5] Although the ability to employ a single type of flap in many different areas of the body is appealing, these flaps have fallen out of favor because of the prolonged waiting time between stages and the advent of numerous other techniques that have been developed for use in different anatomical regions and with varying types of tissue.

Examples of currently used interpolated flaps include:

- Paramedian forehead flap

- Melolabial flap

- Postauricular flap

- Tarsoconjunctival flap

- Inferior turbinate flap

- Pericranial flap

- Facial artery musculomucosal flap

- Deltopectoral flap

- Supraclavicular artery island flap

- Pectoralis major myocutaneous flap

A selection of these is discussed in detail below.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

Interpolated flaps are often based on a named artery that courses through the flap's pedicle and along its long axis; these flaps are said to have axial blood supplies. Regional flaps generally possess axial blood supplies, while most local flaps (eg, advancement, rotation, and transposition flaps) are perfused by random small vessels within the subdermal plexus. The region of tissue perfused by a single vessel is known as an angiosome, and there is usually only 1 in a given interpolated flap.

The paramedian forehead flap, for example, is usually designed to include the supratrochlear artery within it, which will perfuse the entire flap.[6][7] On the other hand, the melolabial flap does not ordinarily contain a named vessel but rather perforating branches from the angular, nasal, and superior labial arteries. Some flaps, such as the deltopectoral flap, contain named vessels, eg, the perforating branches from the internal mammary artery, in the proximal portion of the flap, but are perfused via the subdermal plexus in the distal aspect. In these cases, the distal portion of the flap may suffer from decreased reliability, which somewhat negates the advantages of selecting an interpolated flap. Because of this, some surgeons prefer to delay the deltopectoral flap. This involves elevating the flap but then replacing it into its donor site rather than insetting it into the defect, with a plan to transfer the flap 2 to 3 weeks later.[8] Delaying the flap insert 2 to 3 weeks after the initial flap evaluation to increase blood flow and avoid a decrease in perfusion flap during surgery is recommended. This helps open choke vessels within the flap and improve perfusion in the distal angiosome. The skin at the distal aspect of the deltopectoral flap, usually supplied by the thoracoacromial artery, no longer has an axial blood supply when the flap is elevated. Hence, it depends on random perfusion via the subdermal plexus. By delaying the flap inset, the perfusion in the distal angiosome is improved, making it less vulnerable to ischemia.

Generally, however, most other interpolated flaps are very reliable because of their axial blood supplies unless the flap transfer involves twisting the pedicle to the extent that the vessels become obstructed. Another advantage of including an axial blood supply within a flap is that the usual ratios that govern the length of a flap relative to the width of its pedicle, critical considerations for ensuring reliable perfusion of local flaps, do not apply, thereby permitting the surgeon to reconstruct larger defects, or defects located farther from their flap donor sites. After the interpolated flap is raised and inset, the bridging pedicle is left to allow vascular ingrowth from the recipient site to the flap. For most paramedian, melolabial, and postauricular flaps, this connection is maintained for 3 weeks, and then the pedicle is divided. For deltopectoral flaps, 4 to 6 weeks may be required before the pedicle can be divided safely.[9]

Indications

Interpolated flaps are used when insufficient skin or tissue is nearby to cover a surgical defect with primary closure or an adjacent local flap. The paramedian forehead flap is especially useful for larger defects that are deep or full-thickness and located on the tip of the nose.[10] Melolabial interpolation flaps are useful on the distal third of the nose, especially on the ala, in situations where adjacent tissue transfer or full-thickness grafts are impractical.[11][12][13] The postauricular interpolation flap is utilized in medium-to-large defects on the helix and adjacent antihelix, with or without the loss of small amounts of cartilage, in situations in which single-stage flaps, such as the Antia-Buch technique, are not adequate for coverage or would result in additional deformity.[14]

Mucosal flaps, such as the inferior turbinate and facial artery musculomucosal flap, are typically used for nasal lining reconstruction, often in full-thickness nasal defects or septal perforations.[15][16] In cases where other options are not possible, deltopectoral flaps can be used for treating large wounds on the face, head, or neck. However, the supraclavicular artery island flap is now commonly used for many of these cases.[17][18][19] In many cases, interpolated flaps, such as the supraclavicular artery island flap, are used for reconstructions that would otherwise be undertaken with free microvascular tissue transfer in patients who would not tolerate long periods under general anesthesia because of suboptimal cardiopulmonary health.[20][21]

Contraindications

Using interpolated flaps is contraindicated in patients unwilling or unable to tolerate multiple staged surgical procedures. Likewise, these procedures should be avoided in patients who cannot leave their surgical sites undisturbed, such as patients with cognitive impairment. The paramedian forehead flap is especially liable to manipulation because its pedicle crosses the patient's visual axis and is constantly visible.

Actively infected skin should neither be covered with a flap nor used to create a flap. Defects with residual malignancy shouldn't be closed with flaps unless for palliative purposes. It is advisable to avoid using previously radiated skin or a previous surgical site for repair unless no better options are available. This is because these areas are likely to have compromised vasculature. Smoking is also a relative contraindication to staged island pedicle flaps because it increases the risk of flap necrosis.[22][23] However, procedures with these flaps can usually be performed safely, even in smokers, if the undersurface of the flap is not excessively thinned of fat.

Interpolated flap transfer should be performed with great care in patients receiving anticoagulant therapy or with bleeding disorders. Consultation with the physician who prescribed the medication is prudent before discontinuing anticoagulant therapy. Contacting consulting physicians is also important before operating on individuals with bleeding diatheses.

Equipment

Interpolated flap surgery requires the same equipment as other local or regional flap surgeries, with a few potential additions.

Preoperatively

- Template material (non-stick dressing material, surgical cottonoid, foil suture wrapper, or other material that allows the creation of a template or pattern for the flap; this procedure can also be performed with sterile techniques on the surgical site)

- Local anesthetic

- Surgical scrub/preparation solution

Intraoperatively

- A scalpel (#15 for most applications, although a #12 is preferred in confined spaces, eg, within the nasal cavity)

- Forceps (Adson-Brown or similar)

- Curved iris or Kaye blepharoplasty scissors, preferably serrated (to thin fat from flap if indicated)

- Shea or other fine dissecting scissors

- Skin hooks

- Suture (4-0 or 5-0 absorbable sutures and 5-0 or 6-0 non-absorbable suture)

- Gauze

- Bipolar electrocautery

- Measuring tape or calipers

- A standard soft tissue or flap tray may be required for larger flaps, eg, deltopectoral or supraclavicular artery island flap.

- Doppler ultrasound probe to identify perforators and vascular pedicle (Many authors opt not to use this, but it can be helpful.)

Postoperatively

- Non-adherent petrolatum-soaked gauze ribbon dressing (to place on the raw surface of the pedicle)

- Fluffed gauze or other absorbent material for post-op bulky dressing

- Adhesive dressing material or elastic tape

Personnel

Typically, a surgeon and an assistant can elevate and transfer interpolated flaps, with the assistant mainly helping to control bleeding and cut sutures. However, larger flaps may require general anesthesia and an operating room, which would necessitate the presence of an anesthesia provider and nursing staff.

Preparation

When discussing interpolated flaps before surgery, it can be beneficial to use illustrations to help patients and their families understand the procedure and the postoperative process. Without visual aids, patients may have difficulty grasping the concept. Patients who need reconstruction following Mohs surgery should be shown the defect before flap transfer to understand the extent of the reconstruction required. In some cases, patients may have small lesions and not realize the resection will be more extensive than expected, and this can lead to unpleasant surprises upon learning that multi-stage reconstruction is necessary. However, serial postoperative photographs can help alleviate concerns and demonstrate that the final result will take time. Explaining that minor revisions or touch-up procedures may be indicated in the weeks or months after the initial procedure to obtain optimal results is essential.

Technique or Treatment

Paramedian Forehead Flap

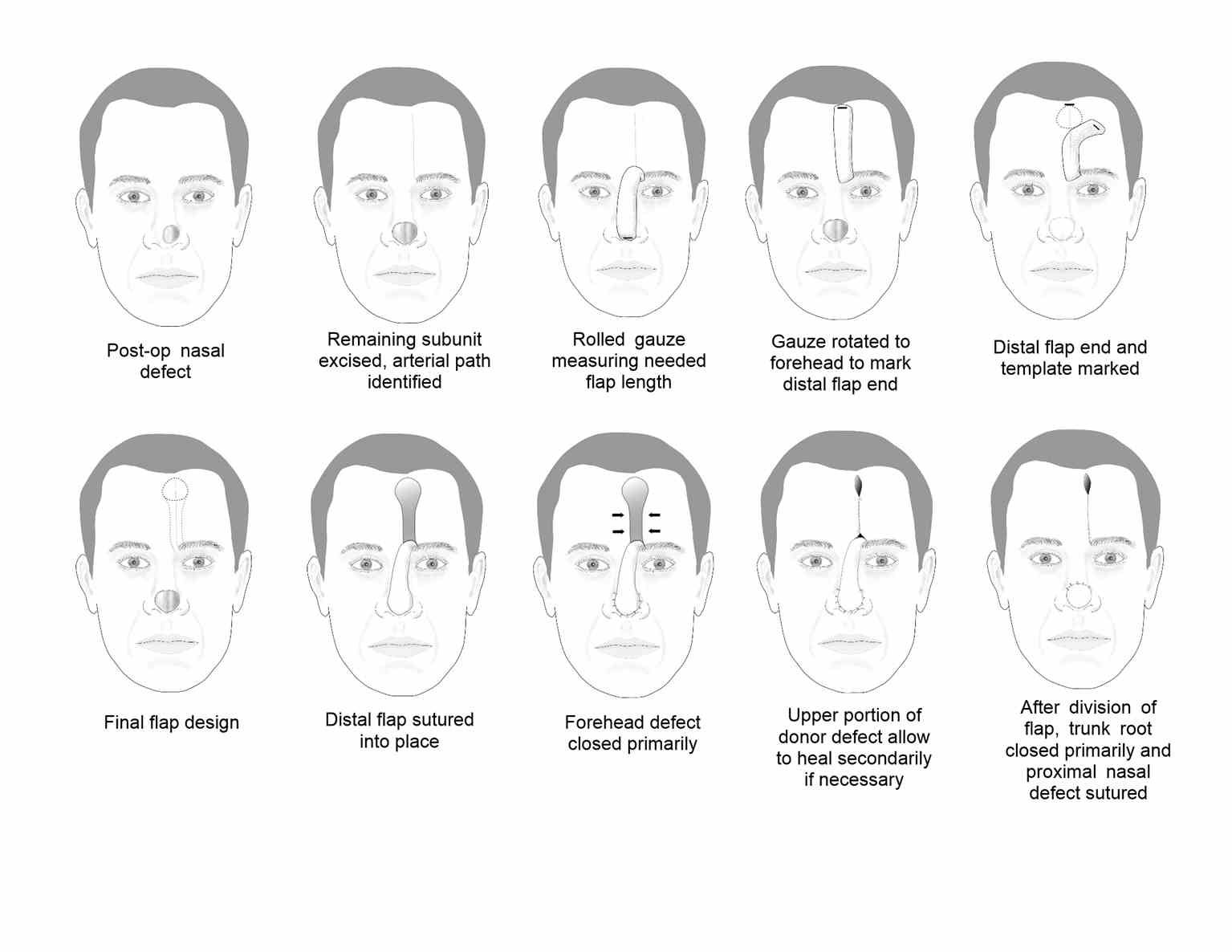

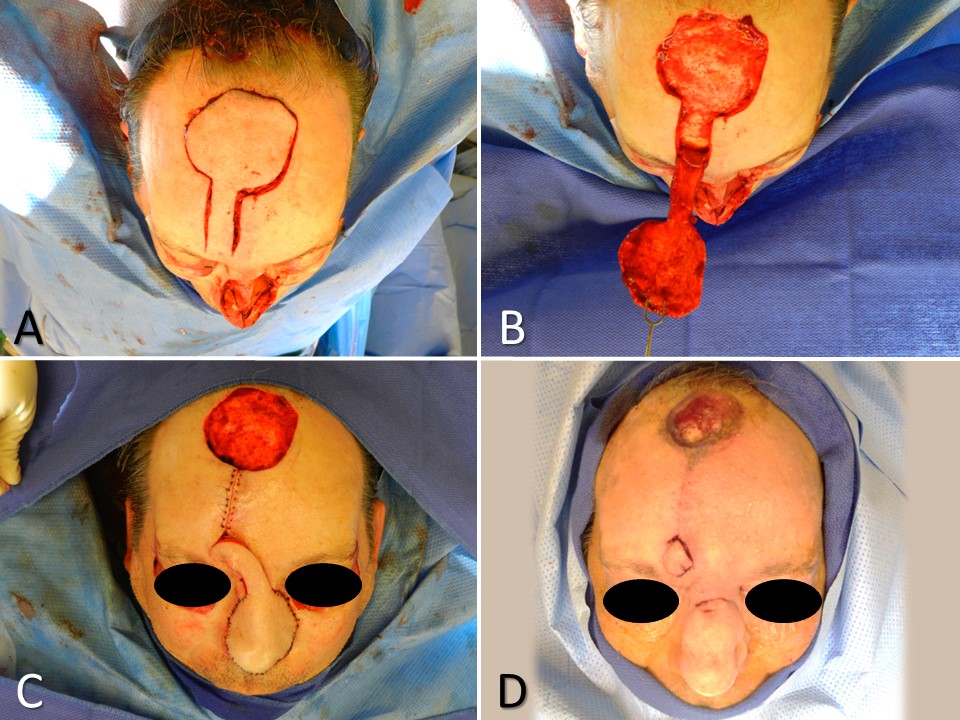

The paramedian forehead flap (PFF) technique was first used in India as early as 700 BC. For many years, a broad midline flap was popular, but in the 1960s, Menick introduced the PFF, which had a much more narrow and mobile pedicle based on the supratrochlear artery. The PFF uses tissue from the forehead to repair larger, deeper defects on the distal nose (see Image. Paramedian Forehead Flap for Nasal Reconstruction) and sometimes provides nasal lining.[7][10] The forehead flap can be combined with other techniques, such as microvascular flaps, cartilage or bone grafts, and mucosal flaps for more extensive defects. The PFF is an axial flap based on the supratrochlear artery, which exits the orbit 1.7 to 2.2 cm from the midline, passing deep to the orbicularis oculi muscle and ascending superficially to the corrugator supercilii muscle. The PFF then passes medial to the eyebrow and through the frontalis muscle, ascending superiorly in the subcutaneous tissue 1.5 to 2 cm from the midline. A similar flap can be based on the supraorbital vessels. Still, the course of the resultant bridging pedicle typically obscures vision in the ipsilateral eye until it is divided, so this remains an option of last resort.

The distal nasal defect is examined before designing the PFF. A template of the final defect is made, and the supratrochlear artery's location and course can be identified using Doppler ultrasonography or anatomic landmarks. The supratrochlear artery runs toward the scalp within 3 mm of a line drawn vertically upward from the medial canthus. Alternatively, a pedicle may be created from the glabellar midline to 1.2 cm laterally.[6] If more than 50% of an anatomic subunit is involved in the surgical defect, removing the remainder of the subunit is often preferable to obtain a better aesthetic result.[11] A defect template is made, and then tubed gauze or another flexible material is used to measure the needed length for the flap to rotate and reach the defect from the pedicle base. The tube gauze is rotated to the forehead, and the inverted template pattern is marked at the uppermost aspect of the pedicle. From that area, a 1 to 1.5 cm wide pedicle is drawn down to the planned pedicle base. The flap is then mobilized with its base at the inferior aspect of the forehead and often around the orbital rim. The distal portion of the flap, the part that will fill the defect, is often elevated in a subdermal plane, with the pedicle being elevated in a submuscular plane and the base elevated in a subperiosteal plane. The forehead donor site is closed primarily, and if the broader portion of that defect will not close completely, it is preferable to allow it to heal secondarily rather than to apply a skin graft. The flap is then thinned distally and secured in the nasal defect with simple interrupted sutures. At 3 weeks postoperatively, the pedicle trunk is excised, and its base defect is closed primarily. If there is any question about the viability of the flap at the planned division, the pedicle can be pinched to observe the distal flap tip. If it blanches with occlusion of the pedicle, additional time for neo-vascularization should be allowed before division and inset. The incised portion of the nasal flap is then thinned and inset into the defect. Minor revision procedures may be indicated during the coming weeks; discussing this with the patient before reconstructing this flap is best.

When transferring a paramedian forehead flap for a patient with a forehead with a low hairline, a variation of the forehead flap or another repair method may be required to avoid transferring hair-bearing skin to the nose; alternatively, the patient may be counseled that subsequent hair removal will be needed via laser or electrolysis.

Melolabial Flap

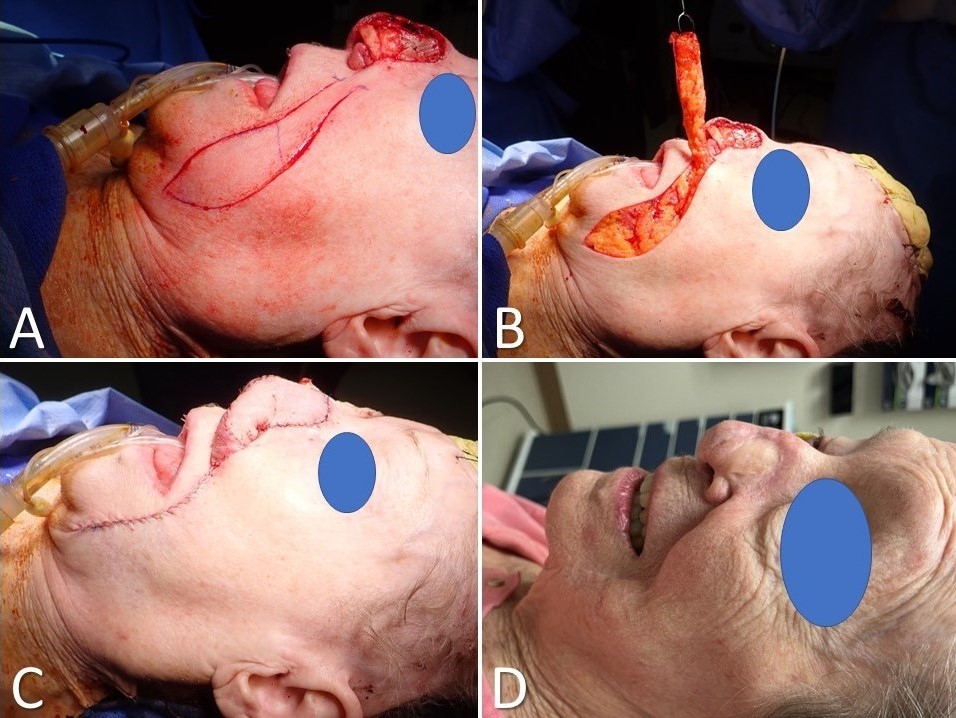

First used in India in about 600 BC, the medial cheek skin is an excellent color and texture match for defects on the caudal third of the nose (Image. Melolabial Flap for Nasal Reconstruction). Based on superiority, the melolabial flap can be designed with a cutaneous or a subcutaneous pedicle, which has greater mobility and a more robust vascular supply than the cutaneous pedicle. For small-to-medium alar defects, an inferiorly-based flap can also be used to avoid the transfer of facial hair. The melolabial flap is random, but it receives ample blood supply from the perforating branches of the angular, nasal, and superior labial arteries.[12][13]

Foil or nonabsorbent surgical dressing is used to make a template of the surgical defect to be repaired. Gauze is rolled into a tube, and an end is held in place in the area of the planned flap base, in and lateral to the nasolabial crease. While the proximal end is held in place, the remainder of the gauze tube is turned to overlap the wound without tension. The most distal portion covering the wound is marked, and the gauze is swung back into the nasolabial crease to mark where the flap should reach. The template is then placed on the cheek with its superior edge placed medially and touching the nasolabial crease. The portion of the template representing the lateral wound edge farthest from the flap is placed most inferiorly (distally) on the cheek, touching the mark previously placed on the cheek. A tapered incision is planned distal to this tissue and parallel to the nasolabial crease to allow closure without a dog-ear deformity. The flap is mobilized, thinned, trimmed, and secured in the recipient wound. The cheek donor site is closed, and the pedicle is wrapped in non-adherent dressing material. The flap's pedicle is divided about 3 weeks after inset.

Postauricular Flap

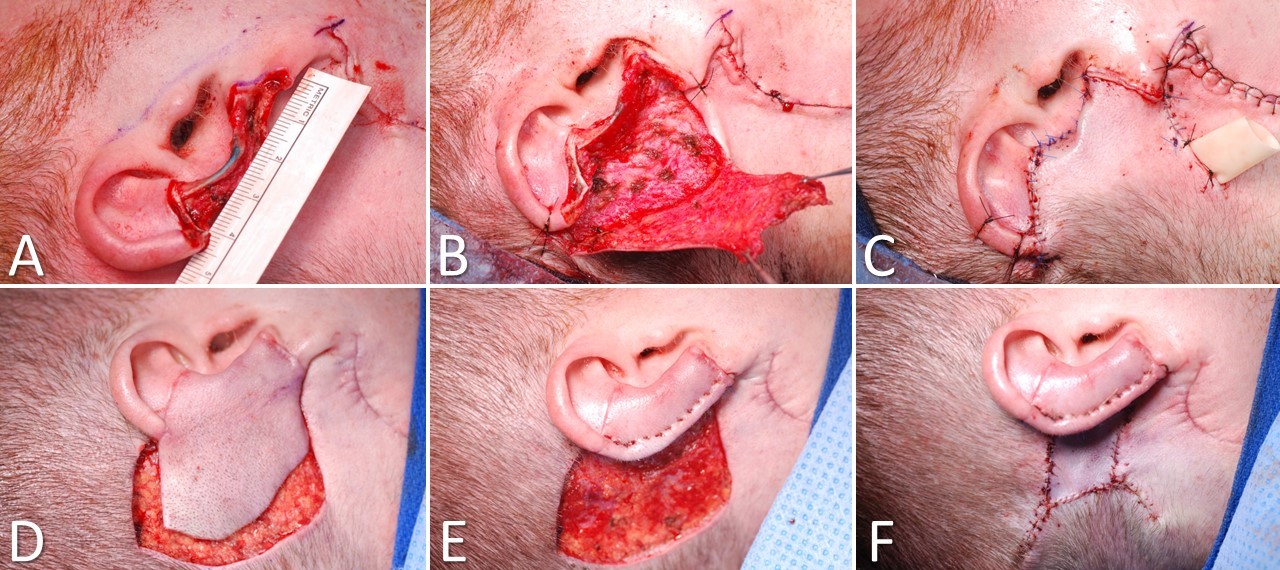

First described by Lewin in 1950, the postauricular interpolated flap provides good coverage and cosmesis in medium-to-large defects of the helix (>2 cm) and adjacent antihelix, with or without the loss of small amounts of cartilage (Image. Postauricular Flap for Auricular Reconstruction). A tubed interpolated postauricular flap may be used for large defects that involve only the helical rim. Branches of the posterior auricular, superficial temporal, and occipital arteries perfuse the broad pedicle of the postauricular flap. Although a random flap, it is rarely affected by vascular necrosis. This flap uses skin from the posterior ear, retro-auricular sulcus, and retro-auricular skin to repair defects of the middle third of the auricular helix and adjacent skin.[14] Scars remain well hidden behind the ear.

Reconstruction begins by making a template of the helical defect. The template is placed behind the ear with its leading (anterior) edge over the posterior ear's loose portion, and the planned flap is drawn with a surgical marker. Lines are directed toward the scalp, gradually tapering outward as they approach the hairline. Burow triangles can be drawn lateral to the base of the pedicle, but the actual excision of the triangles is often unnecessary. Incisions are made through the skin along the planned lines, and the flap is elevated. The surrounding tissue is undermined for a short distance to allow greater tissue mobility, decrease pincushioning, and allow better placement of subcutaneous sutures. The flap is draped to ensure that coverage of the anterior portion of the defect does not cause excessive tension, and the Burow triangle can be excised if necessary. For larger defects, placement of a cartilage graft to maintain the height of the auricle may be considered; the graft is most easily harvested from the nasal septum. Electrocoagulation is used to obtain meticulous hemostasis before the sutures are placed, making every effort to avoid postoperative bleeding. A few interrupted, subcutaneous, absorbable sutures can securely anchor the flap into place, and superficial sutures are placed for fine approximation. Particularly on the posterior aspect of the ear, it is preferable to use absorbable sutures to avoid the need to manipulate the ear for suture removal. If desired, a few bolster sutures can be placed through the flap into the cartilage to recreate the helical sulcus. Division and inset are performed at about 3 weeks. The postauricular donor defect may be closed or allowed to heal secondarily.

Inferior Turbinate Flap

Stemming from a need to provide vascularized mucosa for internal nasal reconstruction without leaving a septal perforation at the harvest site, Murakami et al developed the inferior turbinate flap in 1999.[15] Even though the primary vascular supply of the inferior turbinate arrives through its posterior aspect via the posterior lateral nasal artery, a branch of the sphenopalatine artery, the contribution of the anterior lateral nasal artery, a branch of the facial artery, is sufficient to support the use of the inferior turbinate as a pedicled flap.[24] The inferior turbinate flap is well suited to the reconstruction of the mucosal component of a full-thickness nasal defect, particularly those that result from oncological resection, and require a paramedian forehead flap for skin reconstruction and cartilage grafting for structural support because grafting free mucosa onto a free cartilage graft is unlikely to heal well. The inferior turbinate flap also works very well to reconstruct central and anterior nasal septal perforations with a diameter of less than 2 cm. However, larger defects may be addressed with bilateral inferior turbinate flaps. An interpolated pericranial flap tunneled through the nasal root may be a better choice for larger septal perforations, particularly those that are central or more posteriorly located.[25]

The inferior turbinate is incised through its attachment to the lateral nasal wall, leaving the anterior 1 cm of attachment intact; this may help to fracture the inferior turbinate medially using a Sayre or Boies elevator before making the incision, as a scalpel will not pass through intact bone easily. The turbinate may then be reflected out of the nasal cavity, and the conchal bone dissected out, leaving a flap of soft tissue and mucosa; removal of conchal bone is important because the division of the pedicle at the second stage of the procedure is challenging when bone remains within the tissue bridge. For septal perforation repair, a petrolatum-soaked cotton ball is placed in the naris ipsilateral to the flap to obstruct airflow and prevent desiccation of the pedicle. Pedicle division and placement of septal splints to prevent synechia formation usually occurs 3 weeks after the first stage.

Deltopectoral Flap

The deltopectoral (DP) flap was first described by Aymard in 1917 and remained a highly favored reconstructive option in the early and mid-20th century.[26] This flap is not often used in modern reconstructive surgery, particularly with the widespread availability of microvascular surgery in many centers. However, it remains a valuable technique in centers with unavailable microvascular surgery. The DP flap can reconstruct massive skin and soft-tissue defects of the head, face, oral cavity, pharynx, neck, and chest. Its blood supply is based on perforating branches of the internal mammary artery via the first 3 intercostal spaces. This blood supply is robust and reliable up to the deltopectoral groove overlying the deltoid muscle. Conversely, the blood supply distal to the deltopectoral groove is random. For a long flap that requires the use of this random blood supply, it is best to raise the distal tip back to the deltopectoral groove as a first procedure, then wait 1 week for the blood supply to mature and raise the remainder of the DP flap at that time and inset it. The location of the perforators can be identified by palpating the intercostal spaces at the sternum. A Doppler probe can be used but is not necessary.

The flap is drawn with tapering borders superiorly and inferiorly towards the acromion, gradually narrowing until the desired flap width is achieved. Elevation is performed sharply from distal to proximal, often elevating the fascia of the deltoid and pectoralis major muscles with the flap. Care must be taken not to injure the cephalic vein coursing through the deltopectoral groove. The flap is elevated in this plane up to 2 cm from the sternal border to prevent damaging the perforators. The flap is then rotated and inset with a layered closure. The donor site can typically only be closed partially, and a skin graft is often required over the deltoid muscle. The skin can be harvested from anywhere convenient, though the thigh and abdomen are common donor sites. The interpolated pedicle is broad, and gently tubing it with sutures can minimize oozing. A head-shoulder restraint consisting of adhesive tape used to tilt and secure the head to the ipsilateral shoulder should be applied for the first week. The pedicle is divided at 6 weeks, and most of the interpolated pedicle skin can be rotated and replaced into the donor site.

Supraclavicular Artery Island Flap

The supraclavicular artery island flap (SCAIF) was developed from the acromial flap described by Kazanjian and Converse in 1949. However, the acromial flap had a poorly characterized vascular supply, which led to frequent necrosis of the distal aspect of the flap.[27] Subsequent elucidation of the flap's arterial anatomy in 1997 and later by Pallua et al, however, helped develop the SCAIF into the reliable reconstructive option it is today, supplanting the DP flap in many cases and obviating the need for microvascular surgery for some patients (Image. Supraclavicular Artery Island Flap for Facial Reconstruction).[20][28][29] A primary advantage of the SCAIF over other interpolated flaps is that it can often be transferred via subcutaneous tunneling into the defect rather than requiring a second-stage operation to divide the pedicle. This tunneling prevents the patient from returning to the operating room by leaving the flap's blood supply intact (lowering the risk of tissue necrosis that may occur after pedicle division in some cases). Additionally, the donor site for the SCAIF can generally be closed primarily, unlike the DP flap, decreasing operative time and eliminating donor site pain and morbidity from skin graft harvest. However, some shoulder mobility limitations may arise.[27][30] SCAIF transfer is ideally suited to patients with broad shoulders and short necks, in whom the pedicle is long and capable of reaching as far superiorly as the auricle and lateral skull base, although laryngeal, cutaneous, and oral cavity defects make up the majority of reconstructive targets for this flap.[18][19][31]

In most cases, the supraclavicular artery is a branch of the transverse cervical artery but may occasionally arise from the suprascapular artery. The transverse cervical artery is usually a branch of the thyrocervical trunk, but it may less commonly originate from the proximal subclavian artery. The flap's pedicle is reliably located within a triangle bounded by the posterior margin of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, the clavicle, and the external jugular vein; regardless, its location should still be confirmed with a Doppler ultrasound probe, as up to 20% of patients may not have a supraclavicular artery.[32] Once the pedicle has been located, the flap's skin paddle may be designed, generally between the clavicle anteriorly, the trapezius posteriorly, and the deltoid muscle laterally. The flap is then circumcised and raised in a supramuscular plane over the deltoid, keeping the fascia on the undersurface of the flap to protect the microvasculature. More proximally, elevation continues in a subperiosteal plane over the clavicle, taking care to avoid injuring the supraclavicular artery and its venae comitantes, which provide venous outflow. The flap can then be tunneled and inset into the defect, with a portion de-epithelialized if it is to remain buried.[33]

Complications

Potential complications common to all skin surgery, including flaps, are infection, scarring, bleeding, damage to surrounding anatomy, need for additional procedures, and dissatisfaction with the cosmetic result. More specific to flap surgery is the potential for partial or total flap necrosis with subsequent need for additional reconstructive procedures. Each type of flap will also have potential donor site morbidity or other complications unique to it, such as nasal crusting from an inferior turbinate flap, shoulder scarring from a SCAIF, hairline shifting from a postauricular flap, or even transfer of hair to the tip of the nose with a paramedian forehead flap.

Postoperative Bleeding Complications

The surgical team should pay particular attention to the control of intraoperative and prevention of postoperative bleeding, most commonly experienced in the first 24 to 48 hours after surgery. Salient points are outlined below.

The paramedian forehead flap is especially prone to postoperative bleeding, most commonly from the proximal flap pedicle in the glabella/brow area. This bleeding is best managed as follows:

- Careful and precise but conservative electrocoagulation must be performed at the end of the procedure.

- Hemostatic agents, such as cellulose mesh or Monsel ferric subsulfate solution, may be applied at the base of the flap. Alternatively, a split-thickness skin graft may be placed on the raw surface of the pedicle.

- When dressing the surgical site, extra gauze or other absorbent material should be applied near the flap base, being careful not to apply excessive pressure to avoid strangulation of the flap.

- The patient should return to the office for a dressing change in 1 to 2 days. If excessive drainage is absent, the new bandage may remain in place until the next visit in 5 to 7 days.

Melolabial flaps are not as prone to heavy bleeding but tend to ooze in the early postoperative period.

- Thorugh, but precise, electrocoagulation should be administered before dressing the surgical site, similar to that performed for a paramedian forehead flap.

- A postoperative visit in 1 to 2 days should be scheduled, if possible.

- Any minor bleeding may be addressed during that visit. If no significant bleeding is noted, a less bulky dressing may be applied at that time.

When auricular transposition flaps bleed, they are particularly challenging due to being located in the tight confines behind the ear. Prevention is critical to success.

- Meticulous electrocoagulation must be applied at the end of surgery. Once hemostasis has been obtained, it is often a good idea to rub the wound vigorously with gauze to "battle test" one's work. Any additional bleeding can then be addressed before the inset of the flap.

- The unsutured portion of the pedicle is wrapped with a petrolatum-saturated gauze ribbon, followed by applying a non-adherent surgical dressing and fluffed gauze over the entire surgical site. An elastic adhesive bandage or an otologic dressing (eg, a Glasscock cup) is then applied to run in an anterior-to-posterior direction, thus pulling the ear toward the head. Doing so takes tension off the interpolated flap and helps apply pressure to minimize the risk of bleeding.

Inferior Turbinate Flaps

Inferior turbinate flaps are vulnerable to desiccation of their pedicles due to nasal airflow. Placement of a petrolatum-soaked cotton ball in the nostril on the same side as the turbinate flap to prevent airflow from drying out the flap's pedicle is standard practice. The cotton ball should be replaced daily. The patient should also be discouraged from nose blowing, which may result in more bleeding from the flap and pedicle.

Deltopectoral and waltzing flaps can bleed from their large, wide, exposed pedicles.

- Tubing the pedicle minimizes exposure of raw surfaces prone to bleeding.

- Meticulous hemostasis with bipolar electrocautery at the time of elevation is critical.

Clinical Significance

Interpolated flaps repair surgical and traumatic tissue defects that otherwise would be difficult, if not impossible, to repair with local flap reconstructive techniques. They may also provide a viable alternative to lengthy microvascular free tissue transfer in patients not healthy enough for prolonged general anesthetics.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Interpolated flaps necessitate a comprehensive approach from healthcare professionals, spanning skills in precise surgical techniques, strategic case selection, and ethical decision-making regarding patient autonomy and long-term outcomes. Physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and other health professionals must collaborate through effective interprofessional communication, exchanging expertise to ensure patient-centered care. They share responsibilities in vigilant postoperative monitoring, timely complication intervention, and judicious pain management to enhance patient safety. This coordinated effort leverages diverse perspectives to optimize team performance, improving outcomes and overall patient satisfaction.

Media

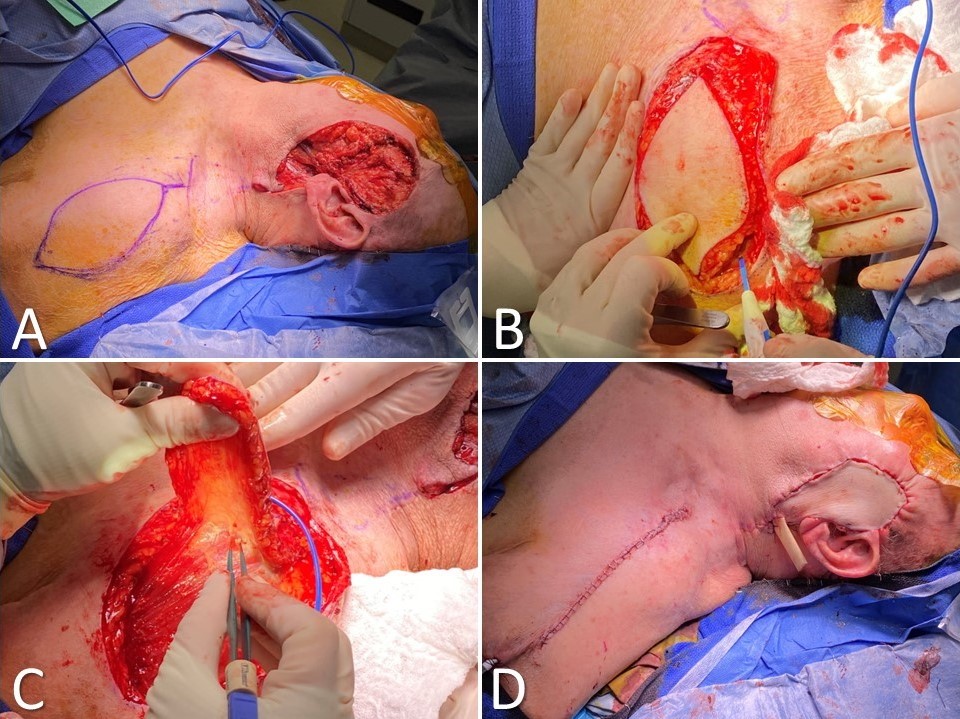

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Paramedian Forehead Flap for Nasal Reconstruction. A subtotal nasal defect due to Mohs resection of basal cell carcinoma requires multilayer reconstruction, including a large paramedian forehead flap (A). The skin paddle is elevated in a subdermal plane, the pedicle in the supraperiosteal plane, and the base in the subperiosteal plane (B). The flap is transferred, and the secondary defect is left to heal by secondary intention due to its size (C). The pedicle is divided 3 weeks later as the secondary defect continues to heal (D).

Contributed by MH Hohman, MD, FACS

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Melolabial Flap for Nasal Reconstruction. A) A subtotal nasal defect due to resection of melanoma requires multilayer reconstruction, including a large melolabial flap; B) The flap is elevated in a subdermal plane; C) The flap is transferred and the secondary defect closed primarily within the nasolabial fold; D) The pedicle is divided three weeks later.

Contributed by Marc H Hohman, MD, FACS

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Postauricular Flap for Auricular Reconstruction. A) A posterior auricular defect due to resection of melanoma, B) The flap is elevated in a subdermal plane, C) The flap is inset over a Penrose drain (a cervical lymph node dissection has been performed as well), D) The pedicle is divided 3 weeks later, E) The flap is wrapped around the medial aspect of the auricle; F) The donor site wound is closed with local advancement and a full-thickness skin graft.

Contributed by Marc H Hohman, MD, FACS

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Supraclavicular Artery Island Flap for Facial Reconstruction. (A) Parotidectomy and skin defect due to dermatosarcoma with supraclavicular artery island flap (SCAIF) drawn out incorporating the supraclavicular artery; (B) the skin paddle is circumcised down to the level of the deltoid muscle; (C) the flap is elevated, ensuring the vascular pedicle remains intact medially; (D) the flap is tunneled into the defect and inset over a Penrose drain, whereas the donor site is closed primarily.

Contributed by MW Herr, MD; KG Anderson MD, FACS; and MH Hohman, MD, FACS

References

Etzkorn JR, Zito PM, Hohman MH, Council M. Advancement Flaps. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28613735]

Prohaska J, Sequeira Campos M, Cook C. Rotation Flaps. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29493993]

Bednarek RS, Sequeira Campos M, Hohman MH, Ramsey ML. Transposition Flaps. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29763204]

Mellette JR, Ho DQ. Interpolation flaps. Dermatologic clinics. 2005 Jan:23(1):87-112, vi [PubMed PMID: 15620622]

Hartman EH, Van Damme PA, Rayatt S, Kuokkanen HO. Return of the waltzing flap in noma reconstructive surgery: revisiting the past in difficult circumstances. Journal of plastic, reconstructive & aesthetic surgery : JPRAS. 2010 Jan:63(1):e80-1. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2009.01.011. Epub 2009 Mar 28 [PubMed PMID: 19329369]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceStigall LE, Bramlette TB, Zitelli JA, Brodland DG. The Paramidline Forehead Flap: A Clinical and Microanatomic Study. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2016 Jun:42(6):764-71. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000000722. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27176864]

Correa BJ, Weathers WM, Wolfswinkel EM, Thornton JF. The forehead flap: the gold standard of nasal soft tissue reconstruction. Seminars in plastic surgery. 2013 May:27(2):96-103. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1351231. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24872749]

Tsuchida Y, Tsuya A, Uchida M, Kamata S. The delay phenomenon in types of deltopectoral flap studied by xenon-133. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1981 Jan:67(1):34-41 [PubMed PMID: 7443857]

Davudov MM, Rahimov C, Fathi H, Mirzajani Z, Aliyeva M. The Use of Pectoralis Major Musculocutaneus and Deltopectoral Flaps in Oromandibular Defects Reconstruction. World journal of plastic surgery. 2019 Sep:8(3):401-405. doi: 10.29252/wjps.8.3.401. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31620345]

Jellinek NJ, Nguyen TH, Albertini JG. Paramedian forehead flap: advances, procedural nuances, and variations in technique. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2014 Sep:40 Suppl 9():S30-42. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000000112. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25158875]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePaddack AC, Frank RW, Spencer HJ, Key JM, Vural E. Outcomes of paramedian forehead and nasolabial interpolation flaps in nasal reconstruction. Archives of otolaryngology--head & neck surgery. 2012 Apr:138(4):367-71. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2012.69. Epub 2012 Mar 19 [PubMed PMID: 22431859]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFader DJ, Baker SR, Johnson TM. The staged cheek-to-nose interpolation flap for reconstruction of the nasal alar rim/lobule. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1997 Oct:37(4):614-9 [PubMed PMID: 9344202]

Nguyen TH. Staged cheek-to-nose and auricular interpolation flaps. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2005 Aug:31(8 Pt 2):1034-45 [PubMed PMID: 16042927]

Johnson TM, Fader DJ. The staged retroauricular to auricular direct pedicle (interpolation) flap for helical ear reconstruction. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1997 Dec:37(6):975-8 [PubMed PMID: 9418767]

Murakami CS, Kriet JD, Ierokomos AP. Nasal reconstruction using the inferior turbinate mucosal flap. Archives of facial plastic surgery. 1999 Apr-Jun:1(2):97-100 [PubMed PMID: 10937085]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePribaz J, Stephens W, Crespo L, Gifford G. A new intraoral flap: facial artery musculomucosal (FAMM) flap. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1992 Sep:90(3):421-9 [PubMed PMID: 1513887]

Bey E, Hautier A, Pradier JP, Duhamel P. Is the deltopectoral flap born again? Role in postburn head and neck reconstruction. Burns : journal of the International Society for Burn Injuries. 2009 Feb:35(1):123-9. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2008.03.015. Epub 2008 Jul 7 [PubMed PMID: 18606502]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHerr MW, Emerick KS, Deschler DG. The supraclavicular artery flap for head and neck reconstruction. JAMA facial plastic surgery. 2014 Mar-Apr:16(2):127-32. doi: 10.1001/jamafacial.2013.2170. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24370537]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceEmerick KS, Herr MW, Lin DT, Santos F, Deschler DG. Supraclavicular artery island flap for reconstruction of complex parotidectomy, lateral skull base, and total auriculectomy defects. JAMA otolaryngology-- head & neck surgery. 2014 Sep:140(9):861-6. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2014.1394. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25104080]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKozin ED, Sethi RK, Herr M, Shrime MG, Rocco JW, Lin D, Deschler DG, Emerick KS. Comparison of Perioperative Outcomes between the Supraclavicular Artery Island Flap and Fasciocutaneous Free Flap. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2016 Jan:154(1):66-72. doi: 10.1177/0194599815607345. Epub 2015 Oct 14 [PubMed PMID: 26467355]

Granzow JW, Suliman A, Roostaeian J, Perry A, Boyd JB. Supraclavicular artery island flap (SCAIF) vs free fasciocutaneous flaps for head and neck reconstruction. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2013 Jun:148(6):941-8. doi: 10.1177/0194599813476670. Epub 2013 Apr 3 [PubMed PMID: 23554114]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGoldminz D, Bennett RG. Cigarette smoking and flap and full-thickness graft necrosis. Archives of dermatology. 1991 Jul:127(7):1012-5 [PubMed PMID: 2064398]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHwang K, Son JS, Ryu WK. Smoking and Flap Survival. Plastic surgery (Oakville, Ont.). 2018 Nov:26(4):280-285. doi: 10.1177/2292550317749509. Epub 2018 Jan 9 [PubMed PMID: 30450347]

Fakoya AO, Hohman MH, Georgakopoulos B, Le PH. Anatomy, Head and Neck, Nasal Concha. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31536243]

Waters CM, Zanation AM, Thorp BD, Shockley WW, Clark JM. Repair of Septal Perforation with Endoscopic-Assisted Pericranial Flap Harvest and Open Rhinoplasty Approach. Facial plastic surgery & aesthetic medicine. 2020 May/Jun:22(3):225-226. doi: 10.1089/fpsam.2020.0008. Epub 2020 Mar 26 [PubMed PMID: 32212970]

Hwang K. The Origins of Deltopectoral Flaps and the Pectoralis Major Myocutaneous Flap. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2016 Oct:27(7):1845-1848 [PubMed PMID: 27763977]

Chiu ES, Liu PH, Friedlander PL. Supraclavicular artery island flap for head and neck oncologic reconstruction: indications, complications, and outcomes. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2009 Jul:124(1):115-123. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181aa0e5d. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19568050]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePallua N, Machens HG, Rennekampff O, Becker M, Berger A. The fasciocutaneous supraclavicular artery island flap for releasing postburn mentosternal contractures. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1997 Jun:99(7):1878-84; discussion 1885-6 [PubMed PMID: 9180711]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePallua N, Magnus Noah E. The tunneled supraclavicular island flap: an optimized technique for head and neck reconstruction. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2000 Mar:105(3):842-51; discussion 852-4 [PubMed PMID: 10724241]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHerr MW, Bonanno A, Montalbano LA, Deschler DG, Emerick KS. Shoulder function following reconstruction with the supraclavicular artery island flap. The Laryngoscope. 2014 Nov:124(11):2478-83. doi: 10.1002/lary.24761. Epub 2014 Jun 10 [PubMed PMID: 24913956]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceEmerick KS, Herr MA, Deschler DG. Supraclavicular flap reconstruction following total laryngectomy. The Laryngoscope. 2014 Aug:124(8):1777-82. doi: 10.1002/lary.24530. Epub 2014 Jan 15 [PubMed PMID: 24431133]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKokot N, Mazhar K, Reder LS, Peng GL, Sinha UK. The supraclavicular artery island flap in head and neck reconstruction: applications and limitations. JAMA otolaryngology-- head & neck surgery. 2013 Nov:139(11):1247-55. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2013.5057. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24158458]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGiordano L, Di Santo D, Bondi S, Marchi F, Occhini A, Bertino G, Grammatica A, Parrinello G, Peretti G, Benazzo M, Nicolai P, Bussi M. The supraclavicular artery island flap (SCAIF) in head and neck reconstruction: an Italian multi-institutional experience. Acta otorhinolaryngologica Italica : organo ufficiale della Societa italiana di otorinolaringologia e chirurgia cervico-facciale. 2018 Dec:38(6):497-503. doi: 10.14639/0392-100X-1794. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30623895]