Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Brachial Plexus

Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Brachial Plexus

Introduction

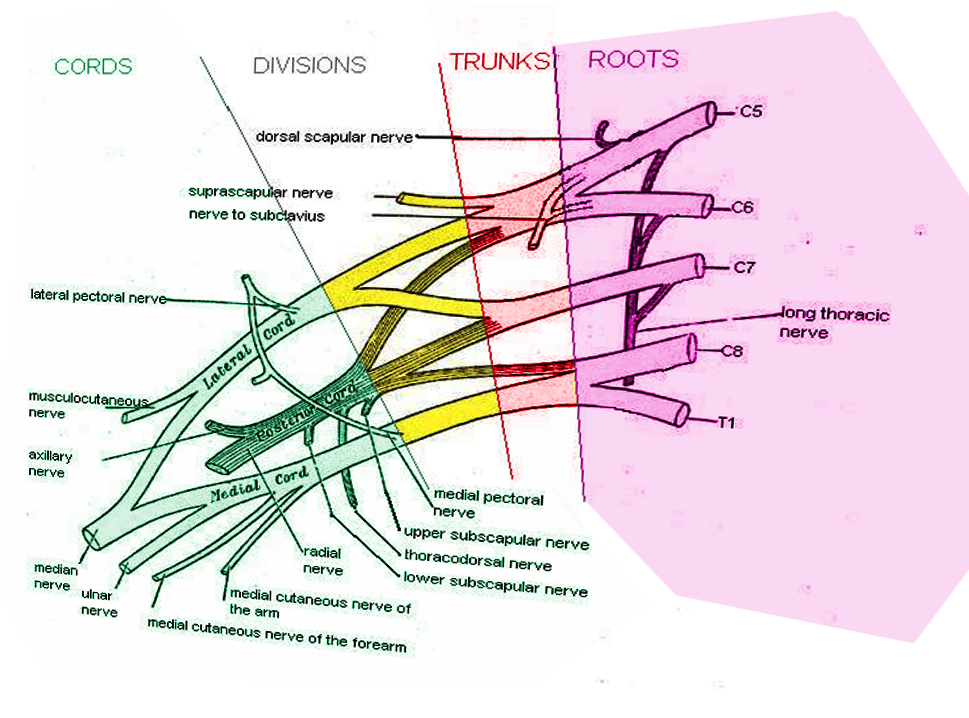

The brachial plexus is a major network of nerves transmitting signals responsible for motor and sensory innervation of the upper extremities, including the shoulder, arm, and hand. It originates from the ventral rami of C5 through T1 spinal nerves.[1][2][3][4] Proximally to distally, the brachial plexus is comprised of roots, trunks, divisions, cords, and terminal branches. Brachial plexus injuries qualify as one of the most debilitating injuries afflicting the upper extremity. Therefore, intricate knowledge of the anatomy of the brachial plexus and its variations is critical to improving the diagnosis, management, and treatment of any injuries to the brachial plexus.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

Ventral rami of the C5 through T1 spinal nerves constitute the roots of the brachial plexus. They come together to give rise to three trunks: superior (C5-C6), middle (C7), and inferior (C8-T1). These trunks subsequently divide into six divisions, located anteriorly and posteriorly. From these divisions, the merging of nerves will form three cords: lateral, posterior, and medial. These cords are named according to their relationship to the axillary artery. Finally, five specific nerves will arise from the cords as the terminal branches of the brachial plexus, allowing specific muscles of the upper limb to perform corresponding actions. These terminal branches include the following: musculocutaneous, axillary, radial, median, and ulnar nerves.[5][6][7][8][9] Aside from these nerves, there are also collateral nerves that exist in the brachial plexus, which innervate the proximal limb muscles as they arise proximal to the ventral rami, trunks, and cords.

Nerve fibers from the anterior division of the brachial plexus are contained in the musculocutaneous, median, and ulnar nerves. These nerves innervate the anterior muscles of the upper arm, forearm, and intrinsic muscles.[10][11][12][11] This innervation mainly provides flexion of the upper limb. Nerve fibers arising from the posterior division, including the axillary and radial nerves, provide innervation to the posterior muscles of the arm and forearm, which in turn allows these compartments to perform the functions of the elbow, wrist, and finger extension.

Embryology

By the start of the fifth week in utero, the human embryo develops forelimbs and hind limbs, observable as “paddle-shaped” buds. The buds of the forelimbs are located posterior to the pericardial swelling, extending from the level of the fourth cervical somites down to the level of the first thoracic somites. This is the stage where peripheral nerves are developed from the growing brachial plexus into the mesenchyme of the developing upper limb. Spinal nerves develop to both dorsal and ventral aspects of the limb in the form of segmental bands. This embryogenic development reveals the development and innervation of the brachial plexus. Segmental bands of the spinal nerves form following the proximal and distal gradient, which indicate that the muscles proximal to the brachial plexus receive innervation by the higher segmental band of C5 and C6. In contrast, the muscles distal to the brachial plexus obtain nerve supply from the lower segmental band of C8 and T1.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The brachial plexus receives the majority of its blood supply from the subclavian artery and its derivatives. The vertebral artery, through its anterior and posterior spinal branches, provides blood supply to the cervical rootlets. The trunks receive blood supply from the superior intercostal and deep cervical arteries, or directly from the subclavian artery. The cords are supplied by the subclavian, subscapular, and axillary arteries.[13]

Nerves

The musculocutaneous nerve arises from C5 and C6 spinal nerves. It innervates all the muscles of the arm anteriorly, enabling motor functions such as flexion of the elbow and supination by the biceps brachii.[14] The median nerve originates from C5 to T1 spinal nerves. It primarily innervates the anterior forearm (with a section innervated by the ulnar nerve) and the hand (thenar and central sections). The median nerve allows pronation of the forearm and flexion of the wrist and digits, together with the opposition of the thumb.[15][16] The ulnar nerve originates from C8 to T1 spinal nerves. It constitutes the innervation of the anterior forearm (with a section innervated by the median nerve) and the hand (hypothenar and central sections). The central section, which involves the palmar and dorsal aspects, is responsible for the adduction and abduction of second to fifth digits, respectively. Unlike the median nerve, which allows opposition, the ulnar nerve is responsible for the adduction of the thumb.[17]

The axillary nerve is the result of the network of C5 and C6 spinal nerves, which arise toward the deltoid muscle allowing for abduction; and the teres minor allowing for external rotation of the shoulder.[18][19][20] The radial nerve, which originates from C5 to T1 spinal nerves, innervates the upper arm and forearm posteriorly. It provides the function of extending the wrist, elbow, and metacarpophalangeal joints of digits and supination by the supinator muscle.

Collateral nerves of the brachial plexus include the following [21]:

- Dorsal scapular nerve innervating the rhomboids

- Long thoracic nerve innervating the serratus anterior

- Suprascapular nerve innervating the supraspinatus and infraspinatus

- Lateral pectoral nerve innervating the pectoralis major

- Medial pectoral nerve innervating both pectoralis major and minor

- Upper subscapular nerve innervating the subscapularis

- Lower subscapular nerve innervating the subscapularis and teres major

- Thoracodorsal nerve innervating the latissimus dorsi

- Medial brachial cutaneous nerve innervating the skin of the arm medially

- Medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve innervating the skin of the forearm medially

The long thoracic nerve is known for allowing the protraction and superior rotation of the scapula, while the suprascapular nerve allows for shoulder abduction (by the supraspinatus muscle) and lateral rotation of the shoulder (by the infraspinatus muscle).

Physiologic Variants

There have been several reports regarding anatomical variations of the brachial plexus. Knowledge of potential anatomic variations is important to mitigate the risks of iatrogenic injuries. For example, a split median nerve pattern was observed with an anomalous muscle on the right forearm of a 35-year-old male cadaver in one study. An anatomical variation was found because of the splitting of the median nerve into two nerves in the proximal third of the forearm, then reuniting at the medial third as a single nerve. Moreover, a study on anatomical variations of the brachial plexus suggested that there is a higher risk of injury for variated nerve branches on fetal cadavers used in the study. Surgeons need to have a better understanding of the possible anatomical variations of the brachial plexus, including extensions, whenever they provide surgical intervention to the upper limb.[22][23][24][25]

Other variations include direct branches from C6 to the Pectoralis Minor and Latissimus dorsi muscles, innervation of the deltoid muscle by C6 and C7 roots, and the lateral pectoral nerve arising from the posterior division of the upper trunk. The median nerve was also observed to be lateral to the axillary artery.[26]

Surgical Considerations

Patients typically lose sensation, motor power, and often experience disabling neuropathic pain following traumatic brachial plexus injuries.[27] Historically, surgical procedures often involved arm amputation, shoulder arthrodesis, and prosthetic replacement for patients with a flailing arm.[22][28] More recent technical advances in peripheral nerve surgery over the last few decades have significantly enhanced the long-term outcomes of brachial plexus treatment.[29]

Clinical Significance

Lesions of the brachial plexus can generally divide into upper and lower lesions. These lesions indicate important landmarks to determine the specific spinal nerves of the brachial plexus that are affected. Erb-Duchenne palsy is due to a lesion in the upper brachial plexus. Klumpke’s paralysis is the result of a lesion in the lower brachial plexus.[30][31]

Erb-Duchenne palsy usually occurs when both the head and the shoulder of the patient are separated by force in cases of birth injury, disk herniation, or accident. The resulting trauma will damage the C5 and C6 spinal nerves affecting the axillary, suprascapular, and musculocutaneous nerves. The loss of axillary and suprascapular nerves is observable when the arm is medially rotated and adducted at the shoulder. Loss of the musculocutaneous nerve presents when the patient’s forearm is extended and pronated, and when the sensory function from the lateral forearm to the base of the thumb is lost. These observations resemble the “waiter’s tip sign,” hence, giving another name to this palsy: the waiter’s tip syndrome.[32]

Klumpke paralysis damages the C8 and T1 spinal nerves. This paralysis is commonly the result of events involving the grabbing an object when falling to break the fall, causing the upper limb to forcefully abduct above the head, leading to spinal nerve trauma. Ulnar nerve and intrinsic muscles of the hand become weak with a loss of sensory function on the median forearm and digits since these nerves are primarily affected. Claw hand sign and ape sign suggest the presence of Klumpke’s paralysis, which may also include manifestations of Horner syndrome. Other than accidents, birth injury, and cases of thoracic outlet syndrome may also lead to the development of the paralysis.[33]

Major terminal branches of the brachial plexus can also suffer injury as a result of fractures, syndromes, or accidents affecting the specific upper limb area.

The musculocutaneous nerve can also be damaged, resulting in the loss of lateral forearm sensation with a weakness of the forearm flexion and supination. However, the probability of the musculocutaneous nerve being lesioned is rare.

Axillary nerve lesions can alter the sensation over the lateral arm and deltoid muscle. These lesions are usually caused by either anterior dislocation or fracture of the surgical neck of the humerus. Another consequence is a weakness of shoulder abduction above 15 degrees.

Median nerve lesions alter the sensation of the lateral three and a half digits and lateral palm. They also cause motor weakness of wrist and finger flexion, pronation, and thumb opposition. Common signs include the ape hand, hand of benediction, and ulnar deviation at the wrist. Lesions of the median nerve can result from pronator teres syndrome, carpal tunnel compression, or supracondylar fracture of the humerus.

Injury or damage to the radial nerve could also develop lesions, as seen in Saturday night palsy, where the axilla is mainly affected. This condition is characterized by a wrist drop brought about by the weakened elbow, wrist, and finger extension. Also, there is a loss of sensory function over the posterior arm, forearm, and dorsal hand. Wrist drop presents as a result of compression to the axilla, usually due to crutches or when sleeping with the arm over a chair (Saturday night palsy). It can also happen from a midshaft fracture of the humerus.

Ulnar nerve lesion affects the sensation of the medial one and a half digits including the hypothenar eminence. It also causes weakness of wrist flexion, finger abduction and adduction, thumb adduction, and finger extension. Claw hand sign and radial deviation at the wrist are the usual signs. Causes of lesions at the ulnar nerve can be the result of fracture of the medial epicondyle of the humerus, the hook of the hamate (from a fall on an outstretched hand), or the clavicle.[12][34]

Thoracic outlet syndrome occurs as a result of the compression of the lower trunk and subclavian vessels. Common causes include a cervical rib, which is an extra rib arising from the C7 vertebra in less than 1% of the population, or a Pancoast tumor, which is a tumor that develops at the apex of the lung. The presentation is similar to Klumpke palsy and includes atrophy of intrinsic hand muscles. However, since subclavian vessels are also compressed, ischemia, pain, and edema of the arm and hand are observed.

Winged scapula occurs due to a lesion of the long thoracic nerve, which arises from the C5, C6, and C7 roots. This lesion commonly occurs as a result of axillary node dissection after a mastectomy. It damages the innervation of the serratus anterior muscle, leading to an inability to anchor the scapula to the thoracic cage. Consequently, the arm can not be abducted above 100 degrees.

The above mentioned muscle-to-nerve associations can be very significant in the diagnosis and management of patients with palsies or paralysis of the upper limb. Determining the area of the upper limb affected and knowing the functions of the muscles according to the affected area, as well as corresponding innervation can immediately provide information as to the possible location of the lesion. These associations can be applied by physicians in the clinical setting, especially in emergency cases.

Other Issues

Though it has a rare incidence, a case of a patient with malignant granular cell tumor (MGCT), which usually occurs in the lower limbs and trunk, was seen to affect the brachial plexus and the suprascapular nerve. A surgical procedure was performed to carefully remove the tumor, preserving the sensory and motor function of the upper limb. This case report shows that tumors can invade and affect the brachial plexus.[35]

Re-implantation as an intervention for complete brachial plexus avulsion has shown definite improvement in the sensory and motor functions of the affected upper limb of patients. However, limited improvement led the researchers to use regenerative cell technology expecting greater and significant progress.

Media

References

Warade AC, Jha AK, Pattankar S, Desai K. Radiation-induced brachial plexus neuropathy: A review. Neurology India. 2019 Jan-Feb:67(Supplement):S47-S52. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.250704. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30688233]

Mahan MA. Nerve stretching: a history of tension. Journal of neurosurgery. 2019 Jan 11:132(1):252-259. doi: 10.3171/2018.8.JNS173181. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30641829]

Glover NM, Murphy PB. Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Radial Nerve. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30521261]

Becker RE, Manna B. Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Ulnar Nerve. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29763067]

Desai SS, Arbor TC, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Musculocutaneous Nerve. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30480938]

Pester JM, Bechmann S, Varacallo M. Median Nerve Block Techniques. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29083641]

Gragossian A, Varacallo M. Radial Nerve Injury. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30725989]

Buchanan BK, Maini K, Varacallo M. Radial Nerve Entrapment. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28613749]

Pester JM, Varacallo M. Ulnar Nerve Block Techniques. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29083721]

Valenzuela M, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Hand Lumbrical Muscles. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30521297]

Valenzuela M, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Hand Interossei Muscles. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30521193]

Aleksenko D, Varacallo M. Guyon Canal Syndrome. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28613717]

ABDULLAH S, BOWDEN RE. The blood supply of the brachial plexus. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. 1960 Mar:53(3):203-5 [PubMed PMID: 13791417]

Tiwana MS, Charlick M, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Biceps Muscle. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30137823]

Sevy JO, Varacallo M. Carpal Tunnel Syndrome. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28846321]

Akhondi H, Varacallo M. Anterior Interosseous Syndrome. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30247831]

Acosta JR, Graefe SB, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Hand Adductor Pollicis. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30252315]

Elzanie A, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Deltoid Muscle. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30725741]

McCausland C, Sawyer E, Eovaldi BJ, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Shoulder Muscles. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30521257]

Maruvada S, Madrazo-Ibarra A, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Rotator Cuff. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28722874]

Bishop KN, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Dorsal Scapular Nerve. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29083775]

Noland SS, Bishop AT, Spinner RJ, Shin AY. Adult Traumatic Brachial Plexus Injuries. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2019 Oct 1:27(19):705-716. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-18-00433. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30707114]

Puffer RC, Bishop AT, Spinner RJ, Shin AY. Bilateral Brachial Plexus Injury After MiraDry Procedure for Axillary Hyperhidrosis. World neurosurgery. 2019 Apr:124():370-372. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.01.093. Epub 2019 Jan 29 [PubMed PMID: 30703585]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDesai K, Warade AC, Jha AK, Pattankar S. Injection-related iatrogenic peripheral nerve injuries: Surgical experience of 354 operated cases. Neurology India. 2019 Jan-Feb:67(Supplement):S82-S91. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.250703. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30688239]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKumar A, Gopalakrishnan MS, Beniwal M. Role of surgery in radiation induced brachial plexus neuropathy. Neurology India. 2019 Jan-Feb:67(Supplement):S53-S54. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.250717. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30688234]

Singhal S, Rao VV, Ravindranath R. Variations in brachial plexus and the relationship of median nerve with the axillary artery: a case report. Journal of brachial plexus and peripheral nerve injury. 2007 Oct 3:2():21 [PubMed PMID: 17915015]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHanyu-Deutmeyer AA, Cascella M, Varacallo M. Phantom Limb Pain. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28846343]

Limthongthang R, Bachoura A, Songcharoen P, Osterman AL. Adult brachial plexus injury: evaluation and management. The Orthopedic clinics of North America. 2013 Oct:44(4):591-603. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2013.06.011. Epub 2013 Sep 6 [PubMed PMID: 24095074]

Leechavengvongs S, Witoonchart K, Uerpairojkit C, Thuvasethakul P. Nerve transfer to deltoid muscle using the nerve to the long head of the triceps, part II: a report of 7 cases. The Journal of hand surgery. 2003 Jul:28(4):633-8 [PubMed PMID: 12877852]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGrahn P, Pöyhiä T, Sommarhem A, Nietosvaara Y. Clinical significance of cervical MRI in brachial plexus birth injury. Acta orthopaedica. 2019 Apr:90(2):111-118. doi: 10.1080/17453674.2018.1562621. Epub 2019 Jan 23 [PubMed PMID: 30669911]

Menticoglou S. Shoulder dystocia: incidence, mechanisms, and management strategies. International journal of women's health. 2018:10():723-732. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S175088. Epub 2018 Nov 9 [PubMed PMID: 30519118]

Davis DD, Roshan A, Canela CD, Varacallo M. Shoulder Dystocia. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29261950]

Merryman J, Varacallo M. Klumpke Palsy. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30285395]

Ramage JL, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Hand Guyon Canal. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30521235]

Jardines L, Cheung L, LiVolsi V, Hendrickson S, Brooks JJ. Malignant granular cell tumors: report of a case and review of the literature. Surgery. 1994 Jul:116(1):49-54 [PubMed PMID: 8023268]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence