Introduction

The lips are an essential aspect of the human face and play a critical role in facial expression, phonation, sensation, mastication, physical attraction, and intimacy. The upper and lower lips are known as, respectively, labium superius oris and labium inferius oris. Both the upper and lower lip contains mucosal membrane, vermilion, and cutaneous surfaces. This article briefly reviews the anatomy, neurovasculature, and musculature of the lips, as well as important surgical and clinical considerations regarding lip pathology.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The upper and lower lips are known as, respectively, labium superius oris and labium inferius oris. Both the upper and lower lip contains mucosal membrane, vermilion, and cutaneous surfaces. While considerations of the lips are often centered on the vermilion zone, the upper lip extends from the nasolabial folds to the inferior margin of the nose, and the lower lip encompasses the region between the lateral commissures and the labiomental crease of the chin. The upper and lower lips intersect at the mouth angle, referred to as the commissure. This is the point at which several muscles involved in lip movement attach.

The upper lip is characterized by a symmetrical pair of paramedian vertical philtral ridges bordering the central depression known as the philtrum, directly below the nasal septum. The philtral ridges and the philtrum are formed by a unique collection of dermal collagen and dense elastic tissue. As elasticity is diminished with age, the philtrum takes on a less prominent appearance. The philtrum is believed to serve as a supply of additional skin to be recruited for oral movements requiring stretching of the upper lip. The inferior margin of the philtrum forms the downward arch of the cupid’s bow, while the underlying fleshy fullness is known as the tubercle or procheilon. Outlining the vermilion borders of the upper and lower lips is a 2 to 3 mm pale convexity known as the white roll, formed by the bulging of the orbicularis oris muscle laying beneath. The upper and lower lips connect to the gums by the frenulum labii superioris and frenulum labii inferioris, respectively.

The vermilion of the lips is comprised of a modified mucous membrane composed of hairless, highly vascularized, nonkeratinized stratified squamous epithelium. This membrane is three to five cellular layers in thickness, in contrast to the 16-layer facial skin. Additionally, the vermilion lacks the typical skin appendages seen in the cutaneous lip, bearing no hair follicles or salivary, sweat and sebaceous glands. The vermilion ranges in color from reddish-pink to brown, depending on ethnicity. The characteristic redness of the vermilion zone is secondary to the paucity of melanocytes and high density of superficial vasculature underlying the membrane. Thus, the blood vessels appear prominent, particularly in those with lighter skin. The red line denotes the division between the dry vermilion and the mucous membrane of the oral cavity in both the upper and lower lips. The transition to the wet labial mucosal is marked by the presence of submucosal salivary glands and the sudden cessation of skin lines.

The lips surround the oral cavity and play a vital role in mastication, facial expression, phonation, tactile sensation, and intimacy. The lips aid in eating by holding food within the mouth and creating an airtight seal that prevents liquids from spilling out of the oral cavity. The lips play a critical role in breastfeeding, by creating a funnel-shape to allow for suction on the nipple. An important component of the speech apparatus, the lips are involved in the creating of bilabial (m, p, b) and labiodental (f, v) consonant sounds and vowel rounding/labialization. Individuals with hearing loss may rely on the lips to lip-read to understand speech without perceiving sounds. The lips are also required for whistling and the playing of wind instruments. The large degree of mobility of the lips allows for substantial movements that enable emotional expression such as smiling and frowning. Additionally, the lips are involved in mediating sexual attraction and are a well-known erogenous zone exploited during acts of kissing.[1][2][3][4]

Embryology

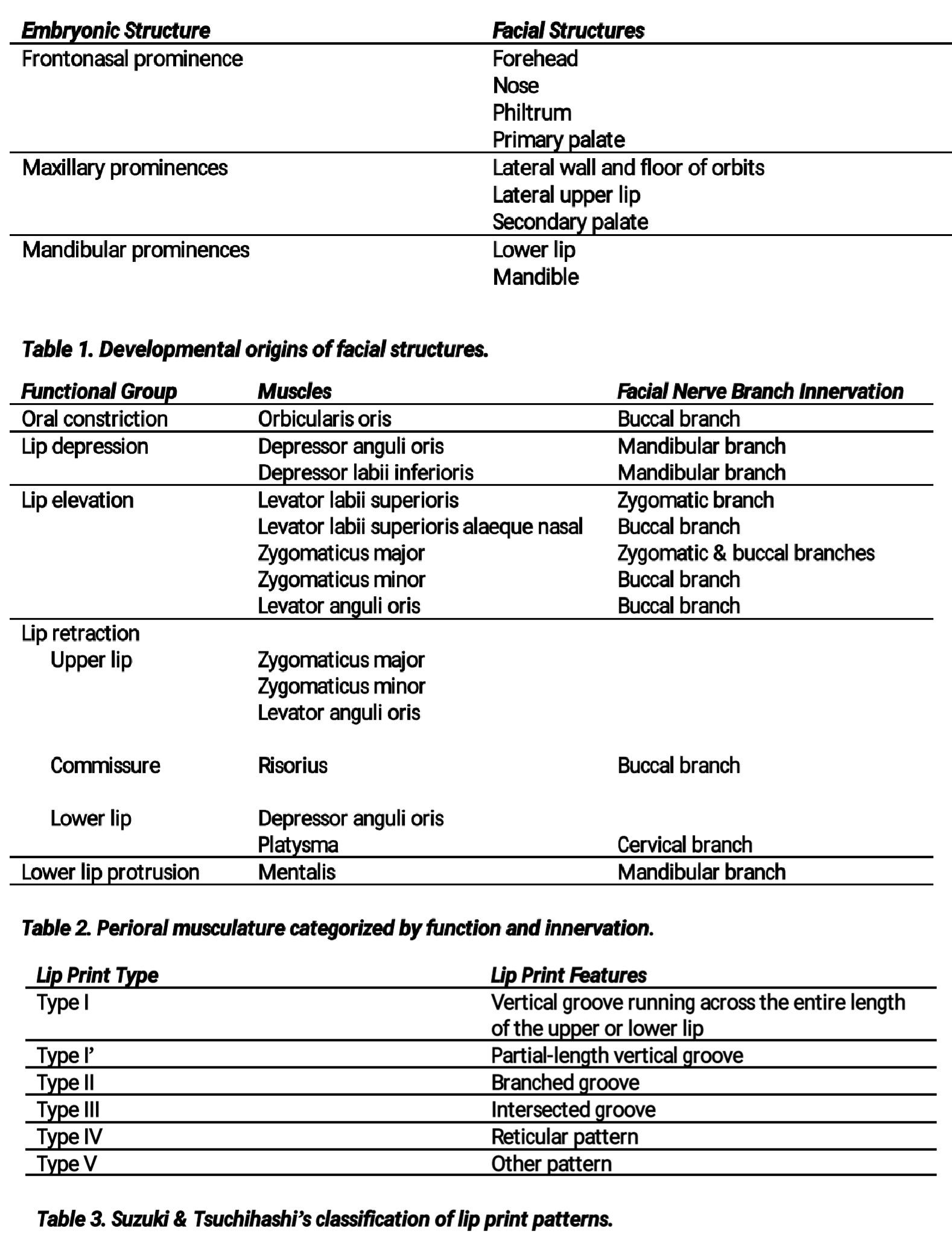

By the third week of gestation, the oropharyngeal membrane becomes apparent as the primordial oral orifice. Surrounding this membrane, the external face is formed by the development of the neural crest-derived frontonasal process covering the forebrain and the first pharyngeal arch composed of mesoderm and neural crest tissues. Further differentiation of the frontonasal prominences gives rise to a pair of lateral nasal processes and a pair of medial nasal processes that eventually give rise to the globular process of the philtrum. The first pharyngeal arch develops into a pair of mandibular processes and a pair of maxillary processes that derive from outgrowths of the arch. The developmental origins of facial structures are outlined in Table 1. The centripetal growth of these prominences results in fusion by the thirteenth week of gestation. Failure of the formation or union of any of these processes may give rise to a developmental defect known as a facial cleft that occurs at a rate of approximately one per 700 births. Clefts may be limited to the lip or extend into the hard palate. Etiologic factors responsible for facial clefts include genetic predisposition, in utero teratogen exposure (antiepileptics, methotrexate, isotretinoin) or maternal viral infections.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The external carotid artery is the principal supply of blood to the lips, via the facial artery giving rise to the superior and inferior labial arteries lateral to the angles of the mouth. The labial arteries are located within the submucosa of the vermilion-mucosa transitional area, deep to the orbicularis oris. Small distributaries branch superiorly and inferiorly from the labial arteries to supply the cutaneous portions of the upper and lower lips. Venous drainage of the lips occurs via the superior and inferior labial veins. These veins directly drain into the ipsilateral facial veins, which empty into the internal jugular vein.

Lymphatic drainage from the upper lip and lateral aspects of the lower lip is directed to the ipsilateral submandibular lymph nodes. The central portion of the lower lip drains into the submental nodes, which may be palpated by bimanual exam by palpating the floor of the oral cavity intraorally while pressing superiorly under the chin with the other hand. There is significant crossover potential in lymphatic drainage patterns from the lip region.

Nerves

The buccal branch of the facial nerve, or cranial nerve VII, provides motor innervation to the orbicularis oris and elevators of the lip and lip angle. The majority of muscles responsible for depression of the lip are supplied via the marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve. The platysma, which is also involved in depression of the lower lip receives its innervation via the cervical branch of the facial nerve.

Recent studies have demonstrated that the depressor labii inferioris muscle is also innervated by a distinct lower cervical branch of the facial nerve.[5] This cervical branch lies approximately 2 cm below the mandible and travels independently toward the depressor labii inferioris muscle. Damage to this branch leads to lower lip palsy, resulting in an asymmetrical, rolled-in appearance of the lip that affects smile aesthetics, speech, and articulation.

The various branches of the trigeminal nerve, or cranial nerve V, provide sensory innervation to the lips. The infraorbital branch of the maxillary division of the trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V2) supplies the upper lip. The mental nerve derived from the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V3) allows for sensation from the lower lip.

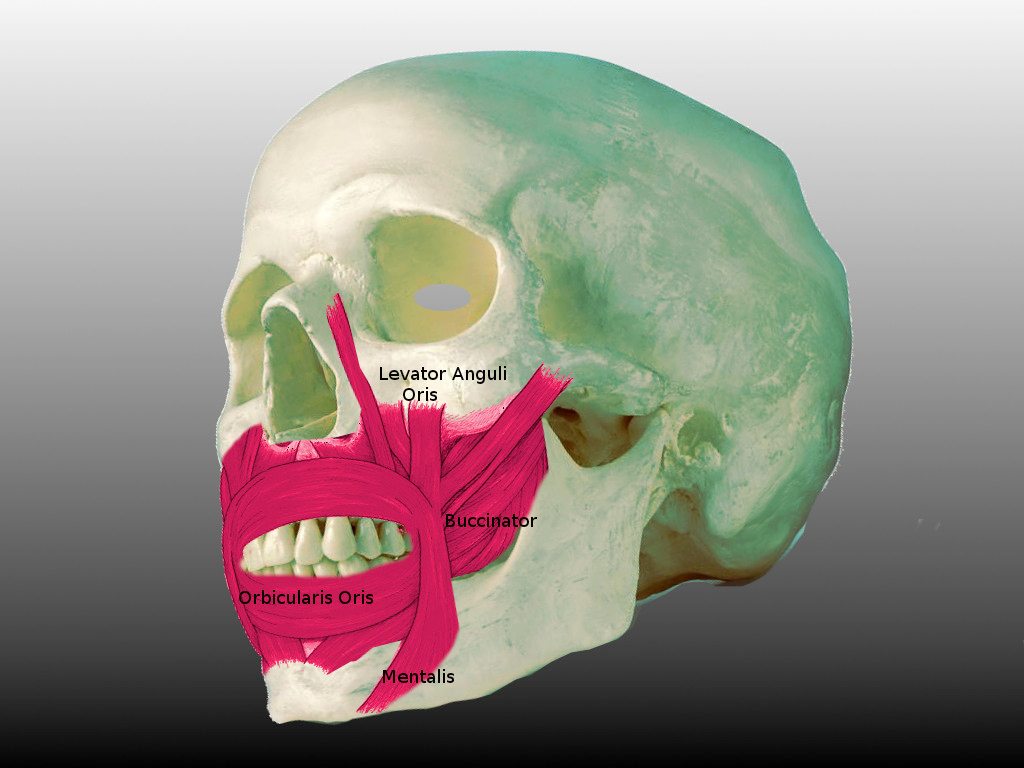

Muscles

Considered muscles of facial expression, the muscles acting on the lips are derived from the second pharyngeal arch mesoderm. These muscles are part of the panniculus carnosus which form attachments with the dermis, resulting in dimpling of the overlying skin.

The principal muscle of the lips is the circumferential orbicularis oris, functioning primarily as a sphincter for the oral aperture. Rather uniquely, the orbicularis oris bears no direct bony attachments but is appended by the other oral muscles that attach to it. Specifically, the nasolabial folds are formed by the insertion of the muscles responsible for lip elevation into the orbicularis oris. At the philtrum, the fibers of the orbicularis oris decussate to insert into the opposite philtral ridge. Interdigitation of the muscle’s fibers at the commissures allows for a scissor-like closure. The perpendicular force vectors formed by the contraction of the orbicular oris results in the generation of relaxed skin tension lines angled radially outward from the oral orifice. Adequate function of the orbicularis oris is requisite for the closure of the mouth, chewing and creating an oral seal.

The modiolus is a fibromuscular tissue structure located 10 to 12 mm superolaterally to the commissures of the mouth. It is formed by the decussation of several facial muscle fibers, including the orbicularis oris, levator and depressor anguli oris, risorius, platysma, buccinator, and zygomaticus major. The modiolus plays a critical role in anchoring these muscles, facilitating mastication, phonation and facial expression. Additionally, the modiolus is responsible for the production of facial dimples in a subset of patients.[6][7]

The additional muscles acting on the lips are divided according to their action in Table 2.

Physiologic Variants

The distinct pattern of grooves and sulci formed by the labial mucosa, known as the sulci labiorum, give rise to a person’s lip print. Much like fingerprints, lip prints are unique to an individual and remain unchanged throughout life. These patterns are unaffected by age, trauma, inflammation, or other factors. Lip prints may be classified according to the schema as described by Suzuki and Tsuchihashi in 1970 (Table 3). The study of lip prints is known as cheiloscopy and may be utilized for forensic identification.

Physiologic pigmentation of the vermilion is commonly observed in darker-skinned patients, although it may be more prominent when it occurs in those with fairer complexions. Melanotic macules are benign, freckle-like regions of focal hyperpigmentation of the labial mucosa. These macules are caused by an increase in melanin deposition within the connective tissue of the lip without a change in the size or quantity of melanocytes. The differential diagnosis of melanotic macules includes intraoral melanoma which must be excluded.[8][9]

Secondary to advancing age and chronic sun exposure, venous lakes may develop on the lips. These benign blanchable blue-purple macule-papules more frequently affect the lower lip. Although benign, venous lakes may be treated via surgical excision or laser therapy due to cosmetic preferences.

A caliber-persistent labial artery (CPLA) is a vascular abnormality of the lip caused by the failure of the inferior alveolar artery to appropriately taper during its superficial course after exiting the mental foramen. This presents as a palpable, tortuous artery coursing 2 to 3 mm inferior to the vermillion border. Eighty percent of cases of CPLA affect the lower lip. Diagnosis is preferentially made via Doppler ultrasonography rather than biopsy. No treatment is required. This is a benign condition.

Surgical Considerations

An important goal of lip reconstruction is to maintain the competence of the oral seal to allow for mastication and phonation. Surgical repair of lesions of the lips poses a specific challenge as significant aesthetic defects are possible with even minor disruptions of the natural vermilion border, cupid’s bow, and white roll. All incisions should be limited to within a single cosmetic unit to minimize the appearance of scars. The cosmetic units of the lips include a single unit comprising the lower lip and 1 medial and 2 lateral units of the upper lip.[10][11][12]

Regional anesthesia of the lips may be achieved via local anesthetic injection or infraorbital and mental nerve blocks for the upper and lower lips, respectively. Prior to incision, the labial arteries should be located and ligated to reduce the risk of hemorrhage.

Mohs micrographic surgery is often the preferred modality for surgical excisions of malignancies of the face, particularly the lips. If Mohs surgery is not utilized, malignancies on the vermilion may be removed via full-thickness or wedge excisions. The apex of the wedge excision serves as a Burow triangle to remove redundant tissue for ease of closure.

Options for surgical closure of lip defects include primary repair, secondary intent, and flap closure. Primary repair is indicated for defects involving less than 30% of the area of the lip. Secondary intention can be utilized for superficial wounds of the vermilion, up to 2.5 cm. Defects extending greater than 2 mm into the cutaneous lip or the orbicularis oris are at increased risk of functional and cosmetic complications. If allowing lip defects to resolve via secondary intention, patients should be closely monitored for the development of lip notching or other malalignments.

While primary and secondary repair can be utilized for management of smaller defects, advancement flaps are commonly used in lip reconstruction to minimize aesthetic complications associated with larger wounds. The foremost intention of advancement flaps is to transition the tension that would be created by a traditional closure to a more aesthetic location. These flaps mobilize tissue of the lateral lip and cheek to reduce deformation of the vermilion-cutaneous border. Defects limited to the vermilion are managed by mucosal advancement flaps, which typically heal rapidly with good cosmetic results. Interestingly, keratinized skin grafted into the oral cavity may eventually transform clinically and histologically into the mucosa. Unilateral advancement flaps, particularly Burow wedge advancement flaps, are often used to repair wounds of the cutaneous aspects of the 2 lateral upper lip cosmetic units. The incision lines may be well-hidden within the vermilion border, nasal sill, and alar crease. Bilateral advancement flaps are used to repair defects of the medial cosmetic unit of the upper lip. By incorporating tissue from both sides of the defect, the natural contours of the lip can be maintained. Additional flap types commonly used in lip reconstruction include the crescentic peri-alar advancement flap, island pedicle advancement flap, rotation flap, and transposition flap. More complex grafts are required for large, full-thickness defects to avoid complication by microstomia. Cautious planning of any flap is required to avoid distortion of free margins. Full-thickness skin grafts have also been used in lip reconstruction but are usually considered suboptimal due to color and texture mismatches. Additionally, the inability to immobilize the lip contributes to an increased risk of graft failure.

Scar lines should be oriented within the natural boundary lines if possible or angled radially along the relaxed skin tension lines to minimize visibility. As notching is a common outcome of surgical interventions to the lips, attempts should be made to avoid scar lines that extend across the vermilion-cutaneous junction. Repair of full-thickness lip defects should occur in four layers (submucosa, orbicularis oris, vermilion border, cutaneous lip), utilizing small-caliber 5-0 or 6-0 sutures. Given the ability of silk sutures to absorb fluid and soften, they are recommended for surgical closure of the vermilion or mucosa. Given the tendency of scars on the lip to depress, wound edges should be aggressively everted during suturing to ensure that the scar will lay flat after healing.

In addition to standard postoperative care, patients should be instructed to minimize talking and facial movements for 48 to 72 hours following surgery. Additionally, patients should avoid using straws for 7 days postoperatively to reduce perioral muscle motion that may disrupt the healing process. Given the proximity of the defects to the oral cavity, patients are typically administered postoperative antibiotics to reduce the risk of wound infections. If pin-cushioning of the flap occurs, intralesional corticosteroids or surgical revision can be employed to improve the appearance of the repair.

Clinical Significance

Variations in the anatomy of the lips and philtrum can be indicative of developmental abnormalities. Smoothening or flattening of the philtrum and a thin upper lip are features commonly seen in fetal alcohol syndrome. A small mouth with a thin upper lip is typical of Prader-Willi syndrome. Additionally, a study of prepubertal boys with autism spectrum disorder reported that a broader philtrum may be characteristic.

Inflammation of the lips, known as cheilitis, may present with dry, eroded, swollen and fissured lips with loss of lip markings. Causes of cheilitis are numerous, including both infectious and non-infectious etiologies. Medications known to precipitate drug-induced cheilitis include isotretinoin, anticholinergics, antidepressants and antiretrovirals, among others. Nutrient deficiencies are a common pathogenic cause of cheilitis, including zinc, riboflavin, niacin, pyridoxine, folic acid, cobalamine, and iron insufficiencies.

Angular cheilitis presents with painful commisural fissures, with or without maceration and crusting. Causes of angular cheilitis include Candida albicans or Staphylococcus aureus infection, ill-fitting dentures, lip-licking, sun exposure, vitamin deficiencies, minor trauma and overclosure of the mouth. Contact cheilitis presents with erythema, edema and scale of the vermilion and circumoral cutaneous aspect of the lips. Allergic contact cheilitis is a relatively uncommon cause of contact cheilitis caused by a delayed hypersensitivity response featuring a prominent eosinophilic infiltrate. Alternatively, irritant contact cheilitis is much more common nonspecific inflammatory response, precipitated by toothpastes, mouthwashes, chewing gum, or cosmetics.

Herpes labialis is caused by infection of the lips with herpes simplex virus (HSV), most commonly HSV-1, although HSV-2 may occasionally be implicated. An initial infection has a more substantial presentation than does reactivation, manifesting as fever, coryza, pharyngitis, gingivostomatitis, cheilitis, and perioral vesicles in young children. Following primary infection, the virus remains dormant in the sensory ganglia of the trigeminal nerve. Triggers for reactivation include ultraviolet (UV) light, trauma, stress, medications, and menstruation. Viral reactivation presents as prodromal pain and/or paresthesias followed by a papulovesicular eruption, most commonly on the vermilion and vermilion-cutaneous border. The vesicles subsequently erode and crust, resolving within ten days. Recurrences are more frequent and severe among immunocompromised patients.

Lip disorders may be a manifestation of systemic disease. Atopic cheilitis, presenting with chronic perioral lichenification, is listed as a minor criterion in the Hanifin-Ruska criteria utilized in the diagnosis of atopic dermatitis. Sjogren disease manifests with an autoimmune-mediated reduction in salivary flow. The resultant xerostomia may lead to difficulty speaking and eating, as well as diffuse dryness of the lips. Discoid lupus erythematosus may be associated with red-and-white, sunburst-like plaques with radiating striations on the labial mucosa and vermilion. Discoid lupus is also known to confer an increased risk of lip squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).

Neoplasms of the lip are an unfortunately common occurrence and may often resemble inflammation of the vermilion, making identification challenging. Actinic cheilitis, the vermilion analog to actinic keratitis of keratinized skin, is similarly associated with chronic UV radiation and may progress into SCC of the lip. Actinic cheilitis is most commonly present on the lower lip due to its more direct sun exposure relative to the upper lip. Presentations of actinic cheilitis include asymptomatic, pain, swelling, erythema or patchy white areas, or scaly crusting of the vermilion. A blurring of the vermilion border is a characteristic feature, although it may be difficult to appreciate in some patients. In addition to strict sun protection, field therapy is often preferred over local treatment for actinic cheilitis.

Malignancies of the upper lip are more consistent with basal cell carcinoma (BCC) of the lips, which often arises from the cutaneous region of the lip surrounding the vermilion. The risk of lymph node involvement or distant metastasis is low. Squamous cell carcinoma of the lips is much more common than BCC of the lips, involving the vermilion of the lower lip in the vast majority of cases. Risk factors for the development of lip SCC include actinic cheilitis, chronic UV exposure, alcohol, tobacco, fair-skin, and immunosuppression. Human papillomavirus has also been implicated in its pathogenesis, although its contribution remains unclear. These lesions present with indurated red or white papules or ulcers on the lips that fail to heal. SCCs of the lips are at high risk of metastases, both at the time of diagnosis and in the years following excision. Despite the high risk of distant spread, long-term survival rate remains relatively high.

Other Issues

Lip color and size have regularly been associated with sexual attraction. Thus lip enhancement has become commonplace in western culture. The popularity of lipstick may be traced back to its evolutionary origins as red lips mimic the vasodilation and engorgement of the lips that occurs during sexual arousal. Studies of subjects’ perceptions of various facial features have identified fuller lips as significantly more attractive than narrower lips. Lip fullness is associated with elevated estrogen levels, suggesting that attraction to lip fullness may be an evolutionary indicator of female fertility. Society’s fondness for fuller lips has led to a recent surge in the popularity of lip augmentation, utilizing the injection of dermal fillers to enhance lip fullness. Although various substances have been injected into the lips throughout history, bovine collagen was introduced into the cosmetic surgery market in the 1980s and became the standard, despite its short-term effects and allergy testing requirement. Novel hyaluronic acid fillers have since been developed and supplanted collagen as the first-line treatment option, with over 700,000 injections performed in the United States in 2017.

Media

References

Li H, Cao T, Zhou H, Hou Y. Lip position analysis of young women with different skeletal patterns during posed smiling using 3-dimensional stereophotogrammetry. American journal of orthodontics and dentofacial orthopedics : official publication of the American Association of Orthodontists, its constituent societies, and the American Board of Orthodontics. 2019 Jan:155(1):64-70. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2018.03.014. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30591168]

Liu X, Daugherty R, Konofaos P. Sensory Restoration of the Facial Region. Annals of plastic surgery. 2019 Jun:82(6):700-707. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000001635. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30557178]

Sălan AI, Mărăşescu PC, Camen A, Ciucă EM, Matei M, Florescu AM, Pădureanu V, Mărgăritescu C. The prognostic value of CXCR4, α-SMA and WASL in upper lip basal cell carcinomas. Romanian journal of morphology and embryology = Revue roumaine de morphologie et embryologie. 2018:59(3):839-849 [PubMed PMID: 30534824]

Naidoo S, Bütow KW. Philtrum reconstruction in unilateral cleft lip repair. International journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery. 2019 Jun:48(6):716-719. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2018.11.003. Epub 2018 Dec 7 [PubMed PMID: 30501933]

Kaufman-Goldberg T, Flynn JP, Banks CA, Varvares MA, Hadlock TA. Lower Facial Nerve Nomenclature Clarification: Cervical Branch Controls Smile-Associated Lower Lip Depression and Dental Display. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2023 Oct:169(4):837-842. doi: 10.1002/ohn.337. Epub 2023 Apr 6 [PubMed PMID: 37021911]

Stojanovič L, Majdič N. Effectiveness and safety of hyaluronic acid fillers used to enhance overall lip fullness: A systematic review of clinical studies. Journal of cosmetic dermatology. 2019 Apr:18(2):436-443. doi: 10.1111/jocd.12861. Epub 2019 Jan 12 [PubMed PMID: 30636365]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSamizadeh S, Pirayesh A, Bertossi D. Anatomical Variations in the Course of Labial Arteries: A Literature Review. Aesthetic surgery journal. 2019 Oct 15:39(11):1225-1235. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjy235. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30204834]

Tijerina JD, Morrison SD, Nolan IT, Vail DG, Nazerali R, Lee GK. Google Trends as a Tool for Evaluating Public Interest in Facial Cosmetic Procedures. Aesthetic surgery journal. 2019 Jul 12:39(8):908-918. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjy267. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30304356]

Mafi AA, Shahverdiani R, Mafi P. Ideal Soft Tissue Facial Profile in Iranian Males and Females: Clinical Implications. World journal of plastic surgery. 2018 May:7(2):179-185 [PubMed PMID: 30083500]

Nakhash R, Wasserteil N, Mimouni FB, Kasirer YM, Hammerman C, Bin-Nun A. Upper Lip Tie and Breastfeeding: A Systematic Review. Breastfeeding medicine : the official journal of the Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine. 2019 Mar:14(2):83-87. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2018.0174. Epub 2019 Jan 25 [PubMed PMID: 30681376]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSalan AI, Camen A, Ciuca A, Patru A, Scrieciu M, Popescu SM, Alexandru DO, Turcu AA. Epidemiological Aspects in Lip Tumors in Oltenia Region of Romania During 2012-2016. Current health sciences journal. 2018 Jan-Mar:44(1):39-47. doi: 10.12865/CHSJ.44.01.07. Epub 2018 Mar 21 [PubMed PMID: 30622754]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWu SQ, Pan BL, An Y, An JX, Chen LJ, Li D. Lip Morphology and Aesthetics: Study Review and Prospects in Plastic Surgery. Aesthetic plastic surgery. 2019 Jun:43(3):637-643. doi: 10.1007/s00266-018-1268-x. Epub 2018 Nov 21 [PubMed PMID: 30465067]