Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Inguinal Region (Inguinal Canal)

Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Inguinal Region (Inguinal Canal)

Introduction

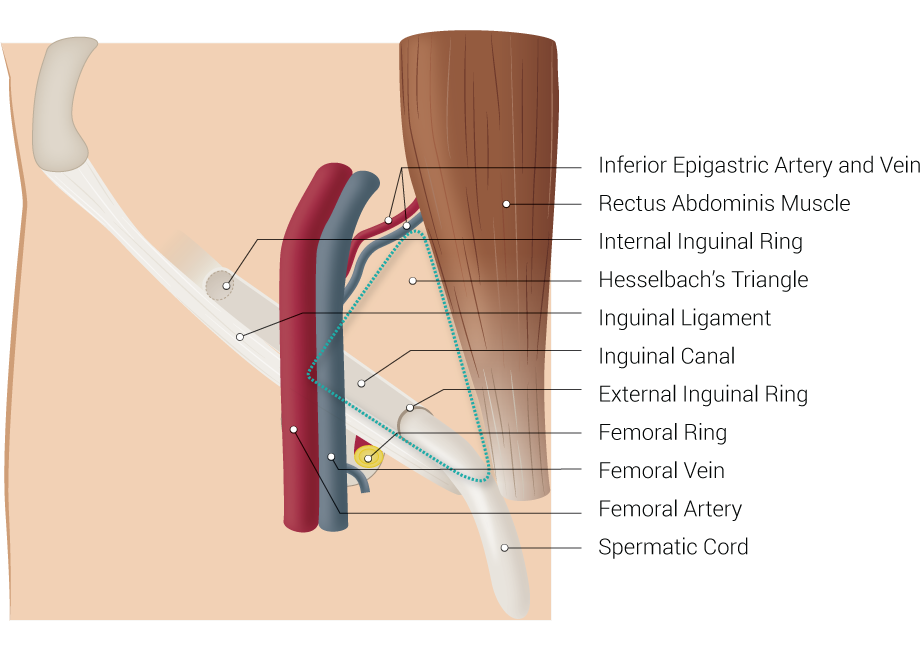

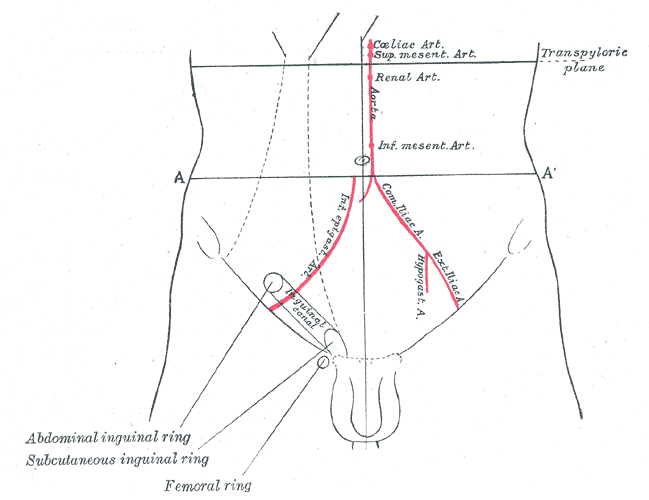

The inguinal region is a relatively anatomically complex region. Amon the several clinically important structures, it contains the inguinal canal which will be the focus of this article. The inguinal canal is a passage in the lower anterior abdominal wall located just above the inguinal ligament. It starts from the internal inguinal orifice, extends medially and inferiorly through the abdominal wall layers and ends in the external inguinal orifice. This canal is about four to six centimeters in length. The length changes from over the growth period from the pediatric age to adulthood. It functions as a passageway for structures between the intra- and extra-abdominal structures. In males, it transmits the spermatic cord, gonadal vessels, and lymphatics. While in females, it transmits the round ligament of the uterus[1][2]. The clinical significance of the area comes from the common surgical problem of inguinal hernias, and to a lesser extent, the inguinal lymphadenopathy and varicocele.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The anatomy of the inguinal canal is of paramount importance for the surgical management of inguinal hernias. As a natural canal with orifices, widening can develop to let other structures from the abdominal cavity pass through to the extra-abdominal space. Chronic increase in abdominal pressure is known to be the main cause of this type of hernias. Inguinal hernias are a common surgical problem that often necessitates surgical repair. A clear understanding of the anatomy of the area is crucial to do a proper surgical repair of the inguinal hernias.[3]

The inguinal canal is made of a floor, anterior wall, posterior wall, and a roof. The floor of the canal that is made of the inguinal ligament. The inguinal ligament is a thickened inferior portion of the external oblique aponeurosis. The anterior wall is made of the external oblique aponeurosis. The posterior wall is made of the transversalis muscle. The more complex part - the roof - is made of the combined fibers of the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscle and aponeurosis including the conjoint tendon. The conjoint tendon constitutes the main part of the medial portion of the posterior wall. Understanding the inguinal anatomy well is essential to understand the various hernias in the region and to perform the different types of surgical repair. It is important for surgeons to note that the mid-inguinal point marks the area between the anterior superior iliac spine and the pubic symphysis. Deep in this location, the femoral artery in the pelvic cavity enters the lower limb. The femoral artery can only be palpated below the inguinal ligament.[4][5][6]

Embryology

During embryogenesis, testicles descend from the posterior abdominal wall and gradually migrate into the scrotal area. This descent or migration movement of the testicles is guided by a cord-like structure called the gubernaculum. It attaches the inferior pole of the testicles to the developing scrotal sac.

With the descent of the testicles, a peritoneal outpouching called the processus vaginalis follows the testicles to the scrotum. Following the descent of the testicles into the scrotum, the processus vaginalis degenerates. This process of degeneration or obliteration may be delayed, or it may fail completely. Failure of closure of the pocessus vaginalis leads to the propensity to develop a number of abnormalities. Peritoneal fluid can travel down a patent processus vaginalis leading to the formation of a hydrocele. Persistent processus vaginalis may increase the risk of development of inguinal hernias.

Failure of the testicles to descend may result in various degrees of undescended testes. This is a common pediatric surgical problem.

Nerves

There are two known nerves that pass within the structures of the inguinal canal. These nerves are the ilioinguinal and the genitofemoral nerves. [1] A third nerve, iliohypogastric nerve, supply sensation to the skin above the genitalia does not pass through the inguinal canal. It pierces the transversus abdominis then the external oblique in the inguinal area.

The ilioinguinal nerve is a branch of L1. It passes through the deep inguinal orifice along with the cord structures. It provides sensation to the anterior perineum and medial and upper thigh. In males, it also provides sensation to the anterior scrotal area. In women, the nerve provides sensation to the labia majora and mons pubis.

The genitofemoral nerve is derived from the L1-L2 spinal nerve roots. It divided above the inguinal canal to the genital branch that passes through the deep inguinal ring with the cord structures, and the femoral branch that passes below the inguinal canal. It provides a motor function to the cremasteric muscle and sensory innervation to the scrotum (genital branch) and the upper thigh (femoral branch) in males, and labia in females.

The ilioinguinal and genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve pass with the cord structures close to the blood vessels course. Entrapment or injury is more likely to happen when wrapping the cord with the mesh or when dissecting the hernial sac. Iliohypogastric injury or entrapment is more likely to happen when suturing the mesh to the internal oblique/conjoint tendon or when closing the external oblique aponeurosis. The incidence of nerve injury after hernia repair is low but variable.[7]

Muscles

The walls of the inguinal canal include the following:

-

An anterior wall that is composed of the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle and reinforced laterally by the internal oblique muscle. The superficial inguinal ring also contributes to the medial third.

-

A posterior wall, also called the floor, is formed by the transversalis fascia, conjoint tendon, and deep inguinal ring.

-

A superior wall, also called the roof, is formed by the medial crus of the aponeurosis of the external oblique, the musculoaponeurotic arches of the internal oblique and transverse abdominal muscles, and the transversalis fascia.

-

An inferior wall, which is formed by the inguinal ligament, is reinforced medially by the lacunar ligament and laterally by the iliopubic tract.

When an individual develops increased intraabdominal pressure, the contents of the abdominal cavity push down on the inguinal ligament. To prevent herniation of the abdominal contents inside the inguinal canal, the posterior wall of the canal contracts while the muscles of the anterior wall tighten to narrow the canal.[8]

There are two openings to the inguinal canal:

-

The deep or internal ring is located just above the midpoint of the inguinal ligament and lateral to the epigastric vessels. The deep ring is formed by the transversalis fascia which provides the posterior covering of the contents of the inguinal ring.

-

The superficial or external ring is the terminal end of the inguinal canal. It is located just superior to the pubic tubercle. The superficial ring has a triangular shape that is made by fibers of the external oblique muscle. These fibers continue to cover the inguinal contents as they descend into the scrotal area. Contiguous with the superficial ring are tendinous fibers (i.e., interligamentous fibers) which function to prevent the ring from enlarging.

Surgical Considerations

Inguinal hernias are a common surgical disease. Understanding the anatomy of the inguinal canal is crucial for the identification and surgically repairing inguinal hernias. Surgical repair of inguinal hernias is based on repairing the hernial defect and reinforcing the posterior inguinal wall after reducing the hernial content and sac. Different methods of repair have been used in the past decades. Formerly, the repair was done by primarily closing the defect or approximating the edges of the widened inguinal ring to provide strength. It was noticed that the recurrence rate of this type of repair was unacceptably high. The explanation to this high recurrence is that the approximated tissue were put under high tension. Forcing the tissue to approximate will result in high tension on the defect edges. Over time, this tension will pull through the tissue resulting in the recurrence of the weakness and hernial defect. Therefore, It was realized that another material is needed to strengthen the posterior wall of the inguinal canal. The idea of using a mesh was then adopted. The mesh provides the necessary strength without exposing tissue to tension.

Surgical repair of inguinal hernias is one of the most common general surgery procedure performed in the U.S. Open inguinal hernia repair includes opening the inguinal canal by incising the external oblique aponeurosis. The inguinal contents are mobilized and dissected to identify, isolate and reduce the hernial sac. Repair and re-inforcement of the posterior wall of the inguinal canal are done with synthetic flat mesh sutured to the inguinal peri-tubercular tissue, incurved part of the inguinal canal, and the conjoint tendon tissue.

Minimally invasive hernia repair approach has been used increasingly in the last decade. Both the Totally Extra-Peritoneal (TEP) and Trans-Abdominal Preperitoneal (TAP) Approaches have been used. Minimally invasive repair involves less interruption of the inguinal canal structures. It includes reducing the hernial content and sac then re-inforcing the posterior inguinal wall pre-peritoneally by placing flat mesh centered on the hernia defect.

Clinical Significance

During inguinal hernia surgery, great care is required to prevent damage to the nerves as it can lead to significant morbidity. In hernia repairs that utilize a mesh the ilioinguinal and genital nerves can be compressed while suturing around the internal oblique muscle. Postoperatively the patient will complain of significant pain or tingling in the innervated areas.

The spermatic cord is easily recognized as it runs in the inguinal canal. It runs together with several small vessels and nerves that connect with the testis. The structures that are of importance in the spermatic cord include the testicular artery, artery to the vas deferens and the cremaster artery. In addition, there are lymphatics and the pampiniform plexus and the genital branch running with the cord. Any combination of these structures can be injured if the spermatic cord is handled inappropriately during surgical dissection.

The inguinal area and canal are known with inguinal hernias. Inguinal and femoral hernias are collectively called groin hernias. Other surgical diseases like hydrocele, varicocele and undescended testis are encountered in the area but are less common.

Indirect Hernia

An indirect hernia can occur when the peritoneal sac enters the inguinal canal via the deep inguinal ring. The hernia protrudes through the external inguinal ring. There is typically associated failure of the processus vaginalis atrophy after birth.

Direct Hernia

In a direct hernia, the peritoneal sac enters the inguinal canal directly via a defect or weakness in the posterior wall of the inguinal canal, usually the transversus abdominis. It usually protrudes directly to the abdominal wall but may exit through the external inguinal ring.

Both inguinal hernias often present in the labia majora or inguinal area as swellings which are more prominent when the individual is upright.

Femoral Hernia

The hernial sac protrudes through the femoral ring, the medial part of the femoral canal. Surgical repair of the femoral hernia is slightly different than inguinal hernias in the open approach. While it is the same in the minimally invasive approach.]

Hydroceles

A hydrocele occurs because of the persistent patency of the processus vaginalis, and it may coexist with an indirect hernia. The condition presents with fluid accumulation in the scrotum. The fluid accumulation can be significant, and most hydroceles need surgical intervention.

Other Issues

The inguinal area is also associated with lymph nodes drainage basin and consequently lymphadenopathy from infections and malignancies. Primary malignancies in the inguinal area are rare, but a lymphoma can present with bilateral lymphadenopathy of the groin. Secondary lymphadenopathy from primary malignancies in the lower limbs, like skin melanoma, are not uncommon. Lipoma of the spermatic cord and malignant tumors like rhabdomyosarcomas are other known tumors of the inguinal area.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Gupton M, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Genitofemoral Nerve. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28613484]

Ramanathan S, Palaniappan Y, Sheikh A, Ryan J, Kielar A. Crossing the canal: Looking beyond hernias - Spectrum of common, uncommon and atypical pathologies in the inguinal canal. Clinical imaging. 2017 Mar-Apr:42():7-18. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2016.11.004. Epub 2016 Nov 5 [PubMed PMID: 27865126]

Kalra A, Wehrle CJ, Tuma F. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Peritoneum. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30521209]

Taghavi K, Geneta vP, Mirjalili SA. The pediatric inguinal canal: Systematic review of the embryology and surface anatomy. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2016 Mar:29(2):204-10. doi: 10.1002/ca.22633. Epub 2015 Oct 10 [PubMed PMID: 26400820]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceDoklamyai P, Agthong S, Chentanez V, Huanmanop T, Amarase C, Surunchupakorn P, Yotnuengnit P. Anatomy of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve related to inguinal ligament, adjacent bony landmarks, and femoral artery. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2008 Nov:21(8):769-74. doi: 10.1002/ca.20716. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18942079]

Lescay HA, Jiang J, Tuma F. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis Ureter. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30422575]

Shaydakov ME, Tuma F. Operative Risk. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30335273]

Hope WW, Tuma F. Incisional Hernia. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28613766]