Introduction

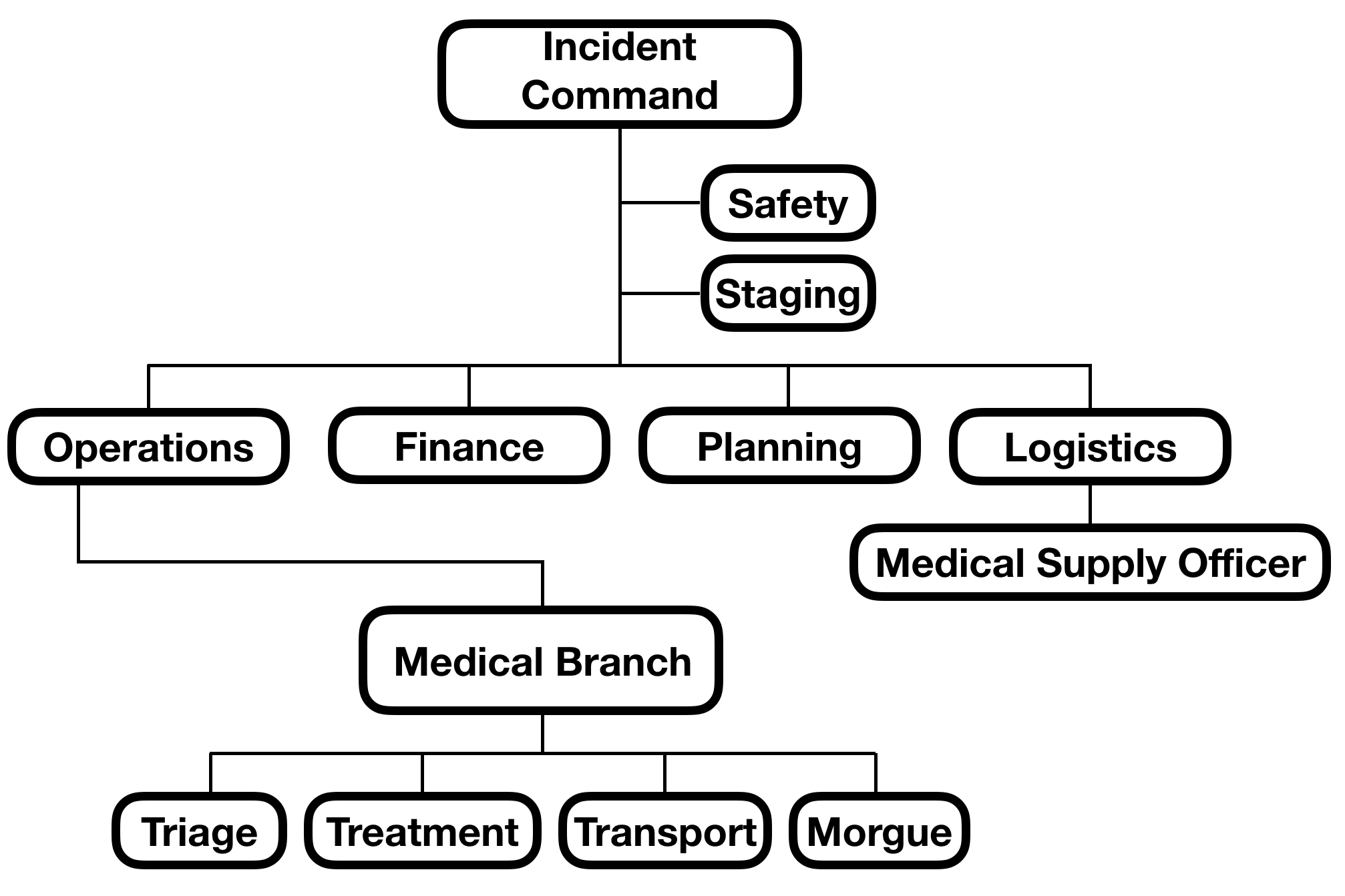

Medical incident command falls under the medical branch of the operations section of the National Incident Management System (NIMS)[1] and provides a conceptual framework for the management of the medical components of disasters and multiple or mass casualty incidents (MCIs). The goal of mass casualty management is to apply available medical resources most effectively to mass casualty incident victims to do the "most good for the most people." The medical incident command structure provides a clear and concise method for how to organize resources for such an incident. Organizationally, an incident commander is responsible for the overall management of the incident. Under the incident commander falls several roles, including operations, planning, logistics, and finance. The operations role oversees the medical branch of an incident. The purpose of the medical branch is to ensure effective triage, on-scene treatment, and transport of MCI victims to appropriate facilities and definitive care. The medical incident command framework is designed to be flexible and scalable and can be applied to incidents with 5, 50, 500, or more patients in need of care.

Issues of Concern

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Issues of Concern

Terminology

NIMS provides specific terminology to describe the organizational structure of incident command. The medical components of a disaster are not assigned their own “command” or “commander,” but are part of the operations section. The term for a functional unit under the operations section is a “branch,” and thus the medical components are the “medical branch;” the role in charge of a branch is a “director.” Regionally, however, terminology may vary, based on the local implementation of NIMS guidelines. Nonetheless, this article will utilize NIMS prescribed terminology.

Role versus Person

A common misconception of the incident command framework is that each "role" must be filled by a unique person. This is not the case. The officer and director roles can be assigned to unique individuals, but this is not required, and a single person may have more than one role, so long as the span of control described in the incident command structure is not exceeded. Major incidents are likely to require assigning each role to a separate individual; smaller incidents may be managed with fewer people. For example, a small incident with 15 patients and mostly minor injuries may still utilize the NIMS framework. A single person may perform the role of incident commander, operations section leader, and medical branch director. Another person may serve as the triage officer, treatment officer, and transport officer, managing the immediate triage and medical needs, and directing units to take patients to hospitals. Because an incident of this duration is likely to be a short-lived incident, not lasting more than a few hours, no logistics, planning, or finance roles are needed. Two individuals may have managed the entire incident. Larger incidents will require more personnel to manage the needed roles.

Organization

The organizational reporting structure is detailed in the included image. The section discussed in this article is primarily the medical branch; the staging officer and medical supply officer are also included on this organizational chart.

Medical Branch Director

The medical branch director is responsible for the overall management of the medical component of the incident. This role reports directly to the Operations Chief. The job of the medical branch director is to supervise and manage the triage, treatment, and transport of patients via the respective officers, and supervise the medical supply officer as well as the morgue officer. The medical branch director communicates with the incident command (in larger operations via the Operations Chief and in smaller operations, they may directly interface with the Incident Commander), the staging officer in some cases, the triage officer, treatment officer, transport officer, and morgue officer.

Triage/Triage Officer

The triage officer is responsible for overseeing the triage of patients, either directly or by managing the individuals who are directly performing triage. The triage officer reports to the medical branch director and communicates with both the medical branch director and the treatment officer. Triage is achieved using a standardized method, such as the START triage method, Sacco Score, FDNY method, or others.[2] The duties of the triage officer role include ensuring the triage of all victims and directing the movement of patients toward the treatment/transport areas of a mass casualty incident. The role of the triage officer is often one of the first roles assigned, as one of the priorities in an MCI is the triage of the victims. The triage officer is responsible for communicating patient counts and needs for supplies and personnel to the medical branch director, and communicating patient movement to the treatment officer.

Treatment/Treatment Officer

The role of the treatment officer is to manage the treatment area, including assigned personnel, and supplies if the medical supply management role is not assigned, and to coordinate with both the triage officer for the movement of patients into the treatment area and the transport officer for the movement of patients out of the treatment area.

The treatment area may vary from an informal area where stabilizing treatment occurs, to a formally designated and staffed treatment location, to a mobile hospital staffed with physicians, paramedics, and nurses. The size and complexity of the treatment area depend on the size and complexity of the incident. A small, multi-casualty motor vehicle collision, for example, may not require a significant treatment area. A large natural disaster, such as a hurricane, may require the deployment of mobile medical units and the setup of field hospitals for the treatment and stabilization of victims.

Transport/Transport Officer

The role of the transport officer is to arrange, track, and document the transport of patients from the scene to an appropriate facility. The transport officer communicates with the incident commander, the treatment officer, and whoever is in the communications role. The communications role will contact hospitals to establish the ability to receive patients, both the number and acuity level. The transport officer must match patients to a hospital based on hospital capacity and patient acuity, and send the patients in a way that does not overwhelm the care capacity of the transport unit. The transport officer is solely responsible for ensuring that all patients who are triaged are accounted for in transport to hospitals or other locations for medical care.

Staging/Staging Officer

The role of a staging officer is not specific to a medical incident and does not fall under the medical branch. The staging officer reports directly to and communicates with the operations section chief or the incident commander. All vehicles and resources assigned to an incident will initially report to a staging area, managed by a staging officer. The staging officer’s responsibilities include keeping a record of resources present in the staging area, monitoring the movement of resources, and dispatching resources to appropriate locations based upon requests by the operations division chief or incident commander.

Medical Supply Officer

The role of the medical supply officer may be filled for extended or very large incidents where the initial supplies brought to the scene will not be sufficient. This role is responsible for predicting the need for, acquiring, and maintaining the organization of all medical supplies. The medical supply officer reports to the logistics officer.

Morgue Officer

The morgue officer is responsible for the management of a collection area for deceased victims. Ideally, the area will have a cool floor surface and be secure. One responsibility of the morgue officer is confirmation of death; the pronouncement of death must be done by a coroner, JP, or other medical authority. Additionally, the morgue officer must maintain accurate records, including time, date, and location where the victim was found, name, and manner of identification, if known. Each victim should be labeled with this information as well. Personal belongings found on the victim should remain with the victim. Victims should only be moved in coordination with incident command and whatever medical authority is present.

Pitfalls of Medical Incident Command

The unpredictable nature of disasters and mass casualty incidents makes planning and conducting prospective research in an actual setting very difficult. Case studies have described retrospective analyses of actual incidents as well as evaluations of MCI Drills, which have value for quality improvement and planning but do not provide the "gold standard" of a randomized, controlled trial. Many criticisms of ICS exist, including those of the medical incident command. One of the often-cited problems or struggles with the medical incident command system is that ICS does not address tactics, strategies, or decision-making. Additionally, the lack of funding to support training decreases the ability to practice making decisions. MCI training, especially joint training among all responders (EMS, fire, police, and hospital personnel), allows for the identification of mistakes and an opportunity to improve MCI plans.[3]

Another difficulty with ICS is that implementation of the ICS system, terminology, and expectations may not be uniform. Fire departments and EMS systems may locally adopt versions of the ICS system that do not specifically follow the terminology or command structure prescribed by NIMS but fit their local reporting structure and needs.[4] While this is effective for most locally managed incidents, the use of local terminology or reporting structure may become more difficult if a larger-scale incident occurs requiring resources not familiar with local terminology or structure.[5]

Clinical Significance

Prehospital personnel is the first medical contact for victims involved in MCI. Effectively applying resources and an organized, systemic method of delivering people appropriately to receiving facilities is, in theory, the key to improved outcomes. Effectively applying out-of-hospital treatments, such as basic airway management and bleeding control has the potential to save lives, and the NIMS structure aids in the organization and application of resources.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Interprofessional communication and coordination is imperative to the success of the medical incident command structure and is truly at the heart of the incident command. Joint training among public safety agencies, disaster response teams, and hospitals is key to identifying mistakes and shortcomings of response plans (PMID).[3] Organizations that take part in joint training are more likely to be familiar with the equipment and team members, thus improving interoperability.

Some large-scale medical incidents require deploying medical care teams for mobile hospitals including physicians and nurses that are required to work with prehospital personnel in an out-of-hospital environment. Fostering understanding of roles of nurses, physicians, and EMS personnel is imperative to successful interprofessional communication in a disaster setting.

Research on mass casualty incidents and disaster is limited to simulated incidents and retrospective reviews of disaster response. One retrospective incident review revealed that many decisions made during the initial evaluation of an incident are made with uncertainty and pressure, and those making decisions are more prone to choose a “workable option” rather than consider all options thoroughly (PMID).[6] Another retrospective evaluation of a training exercise suggested that training should occur with all disciplines represented and should focus on individual communication, triage, and understanding of incident management.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Williams J, Freeman CL, Goldstein S. EMS Incident Command System. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28722893]

Cross KP, Cicero MX. Head-to-head comparison of disaster triage methods in pediatric, adult, and geriatric patients. Annals of emergency medicine. 2013 Jun:61(6):668-676.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.12.023. Epub 2013 Mar 7 [PubMed PMID: 23465555]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGlow SD, Colucci VJ, Allington DR, Noonan CW, Hall EC. Managing multiple-casualty incidents: a rural medical preparedness training assessment. Prehospital and disaster medicine. 2013 Aug:28(4):334-41. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X13000423. Epub 2013 Apr 18 [PubMed PMID: 23594616]

Jensen J, Youngs G. Explaining implementation behaviour of the National Incident Management System (NIMS). Disasters. 2015 Apr:39(2):362-88. doi: 10.1111/disa.12103. Epub 2014 Nov 28 [PubMed PMID: 25441842]

Salzman SM, Clemente Fuentes RW. EMS National Incident Management System. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31869174]

Rimstad R, Sollid SJ. A retrospective observational study of medical incident command and decision-making in the 2011 Oslo bombing. International journal of emergency medicine. 2015:8():4. doi: 10.1186/s12245-015-0052-9. Epub 2015 Mar 4 [PubMed PMID: 25852774]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence