Introduction

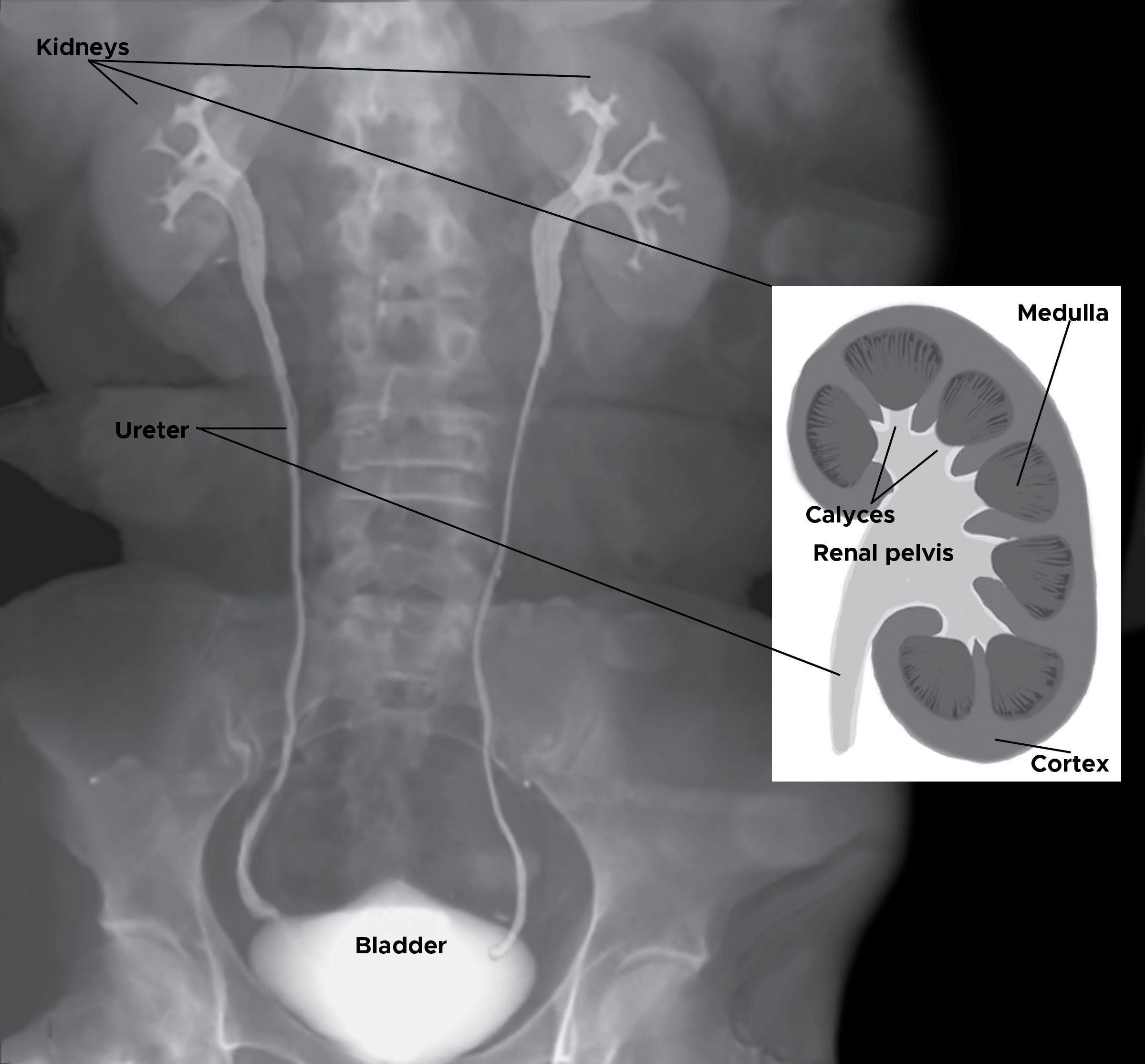

The ureters are bilateral thin tubular structures with a 3 to 4 mm diameter that connect the kidneys to the urinary bladder (see Image. Posterior Thoracolumbar Surface Anatomy). These muscular tubes transport urine from the renal pelvis to the bladder. The ureter's muscular layers are responsible for the peristaltic activity that moves urine from the kidneys to the bladder.

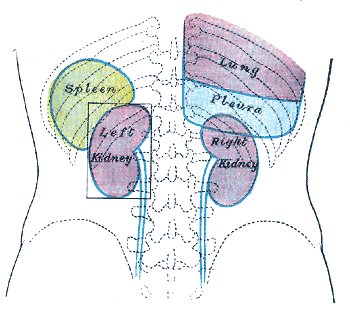

Embryologically, the ureter originates from the ureteric bud—a protrusion of the mesonephric duct that forms part of the embryo's primitive genitourinary system.[1] The ureters begin at the kidneys' ureteropelvic junction (UPJ), which lies posterior to the renal vein and artery in the hilum.[2] The ureters then travel inferiorly inside the retroperitoneal space. These structures pass anterior to the psoas muscle, enter the bony pelvis at the iliac bifurcation, follow the posterolateral pelvic wall, and enter the bladder posterolaterally via the trigone.

The ureters narrow at 2 points along their path: the UPJ and the ureterovesical junction (UVJ). These constrictions are clinically significant, as they are areas where renal calculi can potentially lodge and obstruct urinary flow.[3][4][3]

The UPJ is roughly at the L2 level, where the renal pelvis funnels down inferiorly and transitions into the ureter. This site is commonly involved in proximal ureteral developmental anomalies.

The level of the iliac bifurcation is where the ureters cross over the iliac vessels and may be found within the cleft formed by the external and internal iliac arteries. The ureters are fixed at this location. The ureters then enter to pelvic brim, entering at an acute angle.[5][6][7] While not anatomically constricted, longer stones may have difficulty passing the sharp angulation as the ureter plunges suddenly posteriorly into the pelvis. It is also the point above which rigid ureteroscopy is usually discouraged. The ureter is fixed at this position, so it provides one of the few known locations where the ureter can always be found during open surgery.

The UVJ is where each of the ureters enters the bladder. This site has an antireflux mechanism for preventing retrograde urine flow from the bladder to the ureter and kidneys.

The ureter's blood supply is segmental. The ureteral portion closest to the kidneys receives blood directly from the renal arteries. Abdominal aortic branches and the common iliac and gonadal arteries supply the middle part. The ureters' most distal segment receives circulation from internal iliac artery branches.

The T12 to L2 roots create a ureteric plexus and innervate the ureters. Ureteral pain typically refers to T12-L2 dermatomes.

The ureters lack reliable anatomical landmarks to mark their location besides the 3 physiologic constrictions. Colorectal and gynecologic procedures, particularly laparoscopic hysterectomies, are highly likely to damage these structures.[8]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The ureteral wall comprises 3 main tissue layers: the inner mucosa, middle muscle layer, and outer serosa. Stratified transitional epithelium lines the inner ureteral mucosal lining. Deep to this structure is a relatively thick, fibroelastic lamina propria. The transitional epithelium and lamina propria create a watertight mucosal barrier. The ureters have no submucosa or glandular elements.

Smooth muscle fibers in different orientations surround the mucosa, forming the muscularis layer. This muscular coat has inner longitudinal, middle circular, and outer longitudinal layers. The pacemaker cells that initiate ureteral peristalsis lie in the minor calyces of the proximal renal pelvis. Peristalsis starts from the renal pelvis and propagates in the ureter but is lost at the UVJ's level, where the circular muscular layer disappears.

Surrounding the muscularis is an outer adventitial layer composed of fibroelastic tissue. The adventitia houses the ureteral blood supply, lymphatics, and nerves.

The relatively large renal pelvis gradually funnels into the proximal ureter at the UPJ. The ureters travel inferiorly from the renal pelvis apices at the kidney hila, pass anterior to the psoas, and course over the pelvic brim at the common iliac artery bifurcation. From there, these muscular tubes travel along the pelvis' lateral wall and connect to the urinary bladder. The ureters' abdominal regions are retroperitoneal throughout their course. The gonadal vessels pass anterior to the ureter a third of the way to the bladder. The ureters enter the bladder on the posteroinferior lateral wall, where they fuse with the trigone.[9]

Each ureter traverses the detrusor muscle layers obliquely upon entering the bladder, forming the intramural ureter before emptying into the bladder through the ureteral orifice. This transverse entry into the bladder creates an anti-reflux valvular mechanism that prevents retrograde flow from the bladder to the kidneys during detrusor contractions.[10] The ureteral orifices are about 2.5 cm apart when the bladder is empty but can stretch up to 5 cm apart when the bladder is fully distended.

The right ureter's anatomic relationships differ from those of the left. The right ureter lies near the ascending colon, cecum, and appendix, while the left is close to the descending and sigmoid colon.

Each adult ureter has an average length of 26 cm long, though these tubes' length can range between 22 and 30 cm long. Each ureter follows an "S" shaped curve as it travels from the kidney to the bladder.

The ureter is anatomically and functionally divided into 3 segments: proximal, distal, and intramural.

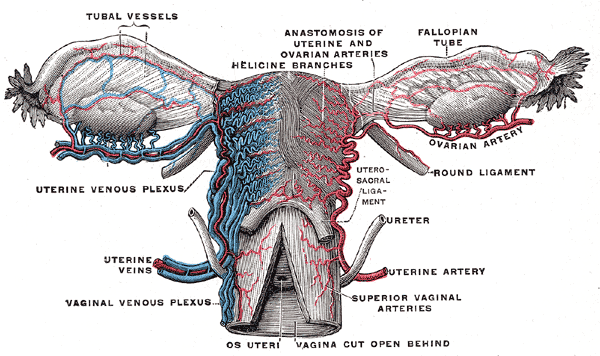

- The proximal ureter (abdominal or upper ureter) is the segment extending from the renal pelvis to the iliac bifurcation. This region is buried mostly within the retroperitoneal fat, except where it passes directly over the psoas muscle. Thus, the proximal ureter can be hard to identify surgically. The genitofemoral nerve lies on the surface of the psoas muscle, just posterior to the proximal ureter. The ureters typically course inferior to the gonadal vessels (testicular or ovarian vessels). This surgically important relationship is best remembered by the phrase "water under the bridge," referring to the ureter's water content and uterine artery's horizontal orientation in this region (see Image. Female Reproductive System Blood Supply).

- The distal ureter (pelvic or lower ureter) extends from the iliac bifurcation to the bladder.[11] This ureteral segment takes a sharp turn posteriorly immediately upon entering the pelvis. From there, the ureter curves back and follows the lateral pelvic wall inferiorly to connect with the posterolateral bladder wall.

- The intramural ureter lies at the UVJ and is typically about 2-cm long. This portion of the muscular tube is buried within the urinary bladder wall on either side and is covered by the fibromuscular Waldeyer's sheath. This fibromuscular covering starts 2 to 3 cm from the outer bladder wall and continues longitudinally until the ureter merges with the trigone. The intramural ureter is aperistaltic, serving as a reflux-preventing mechanism. This segment is the ureter's narrowest portion and the most common location for ureteral calculus obstruction.

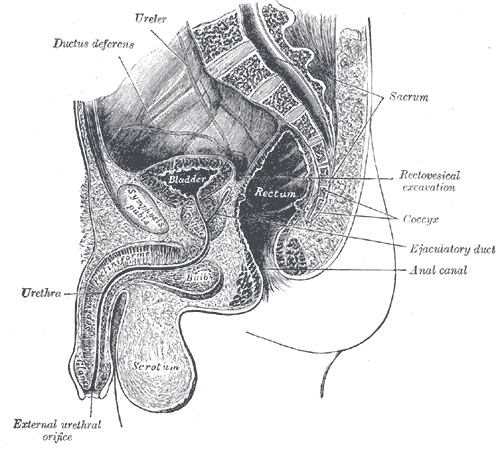

In men, the ureters pass posterior to the vas deferens but anterior to the seminal vesicles before entering the bladder (see Image. Median Sagittal Section of the Male Pelvis). In women, the ureter passes inferior to the insertion of the infundibulopelvic ligament in the pelvis. From there, the ureter travels posterior to the ovaries and fallopian tubes. The ureter lies about 2.5 cm posterior to the uterine artery. The female ureter accompanies the uterine artery and inferior hypogastric nerve plexus in the cardinal ligament. The ureters pass close to the cervix before traveling to the bladder.

Embryology

In week 4, the development of the urinary tract, which includes the kidney, ureter, and bladder, begins with the appearance of the nephrogenic cord in the intermediate mesoderm. The nephrogenic cord gives rise to 3 types of urinary organs. The primitive, cephalically located pronephros appears first. Pronephric ducts also develop craniocaudally and drain the pronephros.

The pronephros and pronephric ducts later disintegrate with the development of the slightly more advanced and caudally positioned mesonephros. The mesonephric ducts (Wolffian ducts) develop craniocaudally alongside the mesonephros. This urinary organ disappears with the development of the metanephros caudad. The mesonephric duct develops a caudal outgrowth, the metanephric diverticulum (ureteric bud), from which the ureters develop.

The metanephric diverticulum arises near the cranial aspect of the metanephros and collecting tubules, which become confluent and form the major calyces. The metanephros gives rise to the permanent kidney. Most of the mesonephros later disintegrates, though some mesonephric ducts remain in the adult male reproductive system.

Ureteric bud development is regulated by different molecular pathways, including glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor rearranged in transfection (GDNF-RET), bone morphogenic protein 4 (BMP4), and Gremlin. A delicate balance exists between ureteric bud growth and ureteric stalk elongation. BMP4 influence suppresses ureteric bud development while stimulating ureteric stalk elongation. Gremlin expression counters BMP4's actions, stimulating ureteric bud development. This finely orchestrated balance ensures that a single ureteric bud develops from each nephrogenic cord.[12]

Disruptions in embryologic development can cause congenital abnormalities of the kidney and urinary tract (CAKUT). Common congenital urinary tract anomalies include partial and complete duplications, preureteral vena cava anomalies (retrocaval ureters), UPJ obstructions, ureteroceles, and ectopic ureters.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The ureters receive blood from multiple arterial branches.[13] The abdominal aorta and renal, gonadal, and common iliac arteries supply the abdominal ureter. These vessels access the ureter medially. Distal ureteral parts receive circulation from the vesical and uterine arteries, which are internal iliac artery branches.

The arteries course along the ureter, creating an anastomotic plexus. This arterial network allows for the safe mobilization of the ureter during surgery when proper exposure from the surrounding structures is crucial. However, the ureter cannot be resected proximally and distally simultaneously, which will overly compromise its blood supply.

The ureter's venous and lymphatic drainage mirrors that of the arterial supply. The lymphatic vessels empty into the internal, external, and common iliac nodes.[14] The left ureter's lymphatic drainage courses to the left paraaortic lymph nodes. Lymph drainage of the right ureter is mainly toward the right paracaval and interaortocaval lymph nodes.

Nerves

The exact role of ureteral innervation is unclear, but the motor impulses for ureteral peristalsis originate from the intrinsic smooth muscular pacemaker sites. The minor calyces house the pacemaker sites within the renal collecting system.[15]

Preganglionic sympathetic stimulation comes from T10 to L2 fibers.[16] The aorticorenal, superior, and inferior hypogastric autonomic plexuses give rise to the postganglionic fibers. Meanwhile, S2 to S4 sacral pelvic splanchnic nerves provide ureteral parasympathetic innervation.

Muscles

The ureter has 3 layers: the mucosa (innermost layer), muscularis (middle layer), and adventitia (outer layer). Transitional epithelium lines the ureteral mucosa. Keratin is primarily responsible for this layer's waterproof properties.

The muscularis is comprised of 2 longitudinal muscle sheets with an intervening circular muscle layer. The circular layer is peristaltic and disappears in the distal ureter segments. Ureteral peristalsis arises from the pacemaker cells within the continuous smooth muscle layer in the minor renal calyces. The adventitia has dense collagen and elastic fibers that house the smaller ureteral vasculature, lymphatics, and nerves.

Physiologic Variants

Congenital UPJ Obstruction

The ureter is narrowed, kinked, or scarred where the UPJ meets the renal pelvis. A short area of narrowing and fibrosis emerges, but the obstruction is rarely complete. Peristalsis is ineffective at the UPJ obstruction, so the kidney becomes functionally blocked and physically obstructed at this region.

Congenital UPJ obstructions in children are twice as common in male individuals as in female persons, with the left side involved twice as often. The incidence of this condition is estimated to be 1 in 1,000 to 1,500. Circular muscle growth disruption and fibrous tissue formation in the UPJ lead to this condition. High insertion of the ureter in the renal pelvis is occasionally a contributing factor, as it causes a sharp angulation at the UPJ.

Accessory Renal Arteries

Accessory or aberrant renal arteries of the kidney's lower pole produce vessels crossing over the UPJ. This condition may cause direct or indirect ureteral obstruction by disrupting normal ureteral muscular development. Severe UPJ obstructions can cause hydronephrosis, pain, and renal cortical thinning. Treatment is surgical in severe or symptomatic cases and conditions requiring renal parenchymal preservation.[17]

Retrocaval Ureter

A retrocaval ureter (preureteral vena cava) occurs when the lumbar subcardinal vein fails to normally atrophy during embryologic development, resulting in posterior entrapment of the right ureter. Symptoms such as hydronephrosis, pain, or hypertension may develop when the ureter is trapped in this location but typically do not appear until the 3rd or 4th decade of life.[18][19] The incidence is approximately 1 in 1100.[20] The treatment for symptomatic cases is surgical.

Vesicoureteral Reflux

Short length or functional incompetence results in the intramural ureter's inability to prevent retrograde urine flow to the kidneys—a condition known as vesicoureteral reflux (VUR). The disorder may arise from early ureteral budding or in association with ectopic or duplicated ureters during embryonic development. Extremely high intravesical pressures may also lead to VUR.

VUR may cause recurrent urinary tract infections. Up to one-third of recurrent urinary tract infections in children have evidence of VUR. The condition may also cause renal scarring, cortical thinning, and atrophy.

VUR is usually classified according to severity. Grades I and II VUR may resolve spontaneously with bladder growth, which increases intramural ureteral length. Low-dose antibiotics help prevent infections in such cases. VUR, categorized as Grade III or higher, typically leads to renal scarring and reflux nephropathy. Surgery is usually necessary to prevent long-term complications.[21]

Ureteral or Kidney Duplication

Abnormal division of the ureteric buds produces ureteral or kidney duplication. Incomplete division results in a bifid ureter with a divided kidney. Complete metanephric diverticulum division produces a bifid ureter with a double kidney.[22][23][24]

In partial ureteral duplication, the proximal ureteral segments are separate but combine distally to form a single ureter before entering the bladder. In complete ureteral duplication, ureters from the same kidney enter the bladder separately. The upper renal moiety drains into the more distal, medial, and inferior ureteral orifice. Meanwhile, the lower renal moiety empties into the more superior and lateral orifice. This pattern is known as the Meyer-Weigert rule. The medial, inferior orifice is obstructed in such cases, while the lateral, proximal ureter is reflux-prone due to its shortened intramural segment.[25]

Ectopic Ureter

An ectopic ureter does not enter the urinary bladder at the trigone but may empty into another site in the genitourinary tract. In males, the anomalous ureter may empty into the bladder neck or prostatic urethra. In female individuals, ectopic ureters may open into the vestibule or vagina.[26] Urinary incontinence often results from the direct communication between the urinary system and parts of the genitals without a sphincteric mechanism.[27]

Horseshoe Kidneys

Horseshoe kidneys have the ureters located anterior to the isthmus immediately below the inferior mesenteric artery. A higher-than-usual rate of UPJ obstructions is associated with horseshoe kidneys.[28]

Surgical Considerations

The most common causes of ureteral injury are iatrogenic.[29] The overall incidence of iatrogenic ureteral injury varies between 0.5% and 10%. The type of procedure that most frequently causes inadvertent ureteral injury is a hysterectomy (54%) due to the proximity of the uterine artery to the distal ureter.[30][31] Each ureter is typically only about 2 cm from the cervix, but the distance can be shorter than 0.5 cm in 12% of women.[32]

Laparoscopic hysterectomies cause more iatrogenic ureteral injuries than open surgeries. Placement of bilateral ureteral catheters or stents reduces this risk but lengthens the overall procedure and produces more genitourinary complications.

Common mechanisms of ureteral injuries during gynecological procedures include severe angulation, crush trauma, laceration, ligation, ischemia, and transection at several locations.[33] The ureteral sites frequently involved include the following:

- At the pelvic brim

- In the cardinal ligament at the level of the cervix, where the ureter and uterine arteries cross

- At the anterolateral vaginal fornix

- Near the UVJ, especially during Marshall-Marchetti-Krantz procedures

- Near the uterosacral ligaments, if thickened due to endometriosis

- Near the broad ligament when suturing for hemostasis

- Near the hypogastric artery, when this vessel needs ligation

In general surgery, colonic procedures are the most frequent causes of iatrogenic ureteral injury. The abdominal ureter is often challenging to identify due to scarring, adhesions, prior surgery, or involvement with the primary pathology. Ureteral stenting or catheterization can minimize inadvertent ureteral damage during colonic surgery.

Isolation of the ureter from the surrounding tissue after tracing its location from a known anatomic landmark may also be considered. The 3 anatomical landmarks used for identifying the ureter during surgery are the UPJ, iliac bifurcation, and UVJ.

Other risk factors for ureteral injuries include malignancy, large pelvic masses, history of pelvic inflammatory disease, previous pelvic or abdominal surgery, and radiation therapy.

Ureteral injuries may present with flank pain, ileus, hematuria, and prolonged high drainage outputs. A urinoma may also form. Laboratory derangements include elevated blood urea nitrogen and creatinine. Ureteral injury may be visualized intraoperatively by injecting a ureteral dye like indigo carmine into the urinary tract. Suspicious fluids in the surgical field may also be tested for creatinine, which is higher in urine than other tissue fluids. A retrograde pyelogram is an imaging study with contrast that can help detect ureteral leaks or obstructions (see Image. Normal Retrograde Pyelogram).

Stenting with or without direct ureteral repair can treat ureteral injuries. Due consideration must be given to the ureteral blood supply to avoid ischemia, scarring, and necrosis. Ureter length may be increased by performing a reimplantation, psoas hitch technique, or Boari flap procedure.[34]

Clinical Significance

Key facts to keep in mind when considering clinical significance are as follows:

- Given the ureteral arteries' locations, surgical exposure of the ureter entails an incision in the lateral abdominal region for the proximal segments and a medial pelvic incision for the distal portions.

- The 3 areas of physiological clinical significance are the sites most commonly involved in obstructive conditions.[35] A retrospective study of 94 patients presenting to the emergency department for colic reported that 60.6% of renal stones were located at the UVJ.[36] This portion of the ureter is aperistaltic, has no circular smooth muscle layer, is anatomically the narrowest, and is surrounded by the detrusor and Waldeyer's sheath.

- The ureters are peristaltic organs. These muscular tubes normally cannot be entirely visualized on a single contrast radiological image, as different portions will be dilated or constricted at any specific moment. Visualization of the entire ureter is known as columnization and suggests ureteral obstruction.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Median Sagittal Section of the Male Pelvis. This illustration shows the anatomic relationships between the symphysis pubis, sacrum, coccyx, retrovesical pouch (retrovesical excavation), ejaculatory duct, ductus deferens, bladder, penis, scrotum, ureter, urethra, scrotum, bulb, anal canal, and external urethral orifice.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Female Reproductive System Blood Supply. Anterior-view illustration showing the fallopian tube vessels, anastomosis of the uterine and ovarian arteries, helicine branches, ovarian artery, uterine venous plexus, uterine artery, and veins, superior vaginal arteries, and vaginal venous plexus. Other structures shown are the ovaries, fallopian tubes, uterus, os uteri, uterosacral ligament, and ureter.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

References

Libretti S, Aeddula NR. Embryology, Genitourinary. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32644735]

Soriano RM, Penfold D, Leslie SW. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Kidneys. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29494007]

Patti L, Leslie SW. Acute Renal Colic. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28613743]

Kamo M, Nozaki T, Horiuchi S, Muraishi N, Yamamura J, Akita K. There are no three physiological narrowings in the upper urinary tract: a new concept of the retroperitoneal anatomy around the ureter. Japanese journal of radiology. 2021 May:39(5):407-413. doi: 10.1007/s11604-020-01080-7. Epub 2021 Jan 9 [PubMed PMID: 33420862]

Zaunbrecher N, Arbor TC, Samra NS. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Internal Iliac Arteries. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30725996]

Arias DG, Marappa-Ganeshan R. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Arteries. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31335039]

Hammond E, Nassereddin A, Costanza M. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: External Iliac Arteries. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30137836]

Yanagisawa T, Mori K, Quhal F, Kawada T, Mostafaei H, Laukhtina E, Rajwa P, Sari Motlagh R, Aydh A, König F, Pallauf M, Pradere B, Miki J, Kimura T, Egawa S, Shariat SF. Iatrogenic ureteric injury during abdominal or pelvic surgery: a meta-analysis. BJU international. 2023 May:131(5):540-552. doi: 10.1111/bju.15913. Epub 2022 Oct 18 [PubMed PMID: 36196670]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceReisner DC, Elgethun MT, Heller MT, Klepchick PR, Hartman MS. Congenital and Acquired Disorders of Ureteral Course. Current problems in diagnostic radiology. 2017 Mar-Apr:46(2):151-160. doi: 10.1067/j.cpradiol.2016.04.002. Epub 2016 Apr 14 [PubMed PMID: 27207823]

Lotfollahzadeh S, Leslie SW, Aeddula NR. Vesicoureteral Reflux. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 33085409]

Tonar Z, Zát'ura F, Grill R. Surface morphology of kidney, ureters and urinary bladder models based on data from the visible human male. Biomedical papers of the Medical Faculty of the University Palacky, Olomouc, Czechoslovakia. 2004 Dec:148(2):249-51. doi: 10.5507/bp.2004.052. Epub [PubMed PMID: 15744389]

Rehman S, Ahmed D. Embryology, Kidney, Bladder, and Ureter. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31613527]

Leslie SW, Sajjad H. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Renal Artery. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29083626]

Kohlmann HW, Respondek M. [Lympho-venous shunts and thromboids in urinary obstruction]. Der Pathologe. 2012 Mar:33(2):152-6. doi: 10.1007/s00292-011-1551-y. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22124726]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDi Benedetto A, Arena S, Nicotina PA, Mucciardi G, Galì A, Magno C. Pacemakers in the upper urinary tract. Neurourology and urodynamics. 2013 Apr:32(4):349-53. doi: 10.1002/nau.22310. Epub 2012 Sep 21 [PubMed PMID: 23002060]

Campi R, Minervini A, Mari A, Hatzichristodoulou G, Sessa F, Lapini A, Sessa M, Gschwend JE, Serni S, Roscigno M, Carini M. Anatomical templates of lymph node dissection for upper tract urothelial carcinoma: a systematic review of the literature. Expert review of anticancer therapy. 2017 Mar:17(3):235-246. doi: 10.1080/14737140.2017.1285232. Epub 2017 Feb 6 [PubMed PMID: 28103449]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAl Aaraj MS, Badreldin AM. Ureteropelvic Junction Obstruction. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32809575]

Chung BI, Gill IS. Laparoscopic dismembered pyeloplasty of a retrocaval ureter: case report and review of the literature. European urology. 2008 Dec:54(6):1433-6. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.09.010. Epub 2008 Sep 17 [PubMed PMID: 18805629]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFadil Y, Bai W, Dakir M, Debbagh A, Aboutaieb R. Retrocaval ureter: A case report and review of the literature. Urology case reports. 2021 Mar:35():101556. doi: 10.1016/j.eucr.2020.101556. Epub 2020 Dec 28 [PubMed PMID: 33437649]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGay SB, Armistead JP, Weber ME, Williamson BR. Left infrarenal region: anatomic variants, pathologic conditions, and diagnostic pitfalls. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 1991 Jul:11(4):549-70 [PubMed PMID: 1887111]

Aeddula NR, Baradhi KM. Reflux Nephropathy. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30252311]

Kaza RM, Garg PK, Ramani S, Jain SK. Triplicate ureter with contralateral duplicate ureter. Annals of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore. 2010 May:39(5):419-20 [PubMed PMID: 20535437]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKozlov VM, Schedl A. Duplex kidney formation: developmental mechanisms and genetic predisposition. F1000Research. 2020:9():. pii: F1000 Faculty Rev-2. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.19826.1. Epub 2020 Jan 6 [PubMed PMID: 32030122]

Dorko F, Tokarčík J, Výborná E. Congenital malformations of the ureter: anatomical studies. Anatomical science international. 2016 Jun:91(3):290-4. doi: 10.1007/s12565-015-0296-8. Epub 2015 Aug 19 [PubMed PMID: 26286110]

Darr C, Krafft U, Panic A, Tschirdewahn S, Hadaschik BA, Rehme C. Renal duplication with ureter duplex not following Meyer-Weigert-Rule with development of a megaureter of the lower ureteral segment due to distal stenosis - A case report. Urology case reports. 2020 Jan:28():101038. doi: 10.1016/j.eucr.2019.101038. Epub 2019 Nov 14 [PubMed PMID: 31763165]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMikuz G. [Ectopias of the kidney, urinary tract organs, and male genitalia. German version.]. Der Pathologe. 2018 Sep:39(5):415-423. doi: 10.1007/s00292-018-0474-2. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30135974]

Murtaza B, Mahmood A, Niaz WA, Akmal M, Ahmad H, Saeed S. Ureterovaginal fistula--etiological factors and outcome. JPMA. The Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association. 2012 Oct:62(10):999-1003 [PubMed PMID: 23866433]

Kirkpatrick JJ, Leslie SW. Horseshoe Kidney. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28613757]

Douissard J, Ris F, Morel P, Buchs NC. Current Strategies to Prevent Iatrogenic Ureteral Injury During Colorectal Surgery. Surgical technology international. 2018 Jun 1:32():119-124 [PubMed PMID: 29791695]

Matsumura Y, Iemura Y, Fukui S, Kagebayashi Y, Samma S. [Iatrogenic Injuries of Urinary Tract : Outcomes of Surgical Repairs]. Hinyokika kiyo. Acta urologica Japonica. 2018 Mar:64(3):95-99. doi: 10.14989/ActaUrolJap_64_3_95. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29684957]

Barbic M, Telenta K, Noventa M, Blaganje M. Ureteral injuries during different types of hysterecomy: A 7-year series at a single university center. European journal of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology. 2018 Jun:225():1-4. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2018.03.039. Epub 2018 Mar 23 [PubMed PMID: 29626708]

Hurd WW, Chee SS, Gallagher KL, Ohl DA, Hurteau JA. Location of the ureters in relation to the uterine cervix by computed tomography. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2001 Feb:184(3):336-9 [PubMed PMID: 11228483]

Chan JK, Morrow J, Manetta A. Prevention of ureteral injuries in gynecologic surgery. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2003 May:188(5):1273-7 [PubMed PMID: 12748497]

Engelsgjerd JS, LaGrange CA. Ureteral Injury. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29939594]

Gild P, Kluth LA, Vetterlein MW, Engel O, Chun FKH, Fisch M. Adult iatrogenic ureteral injury and stricture-incidence and treatment strategies. Asian journal of urology. 2018 Apr:5(2):101-106. doi: 10.1016/j.ajur.2018.02.003. Epub 2018 Feb 17 [PubMed PMID: 29736372]

Eisner BH, Reese A, Sheth S, Stoller ML. Ureteral stone location at emergency room presentation with colic. The Journal of urology. 2009 Jul:182(1):165-8. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.02.131. Epub 2009 May 17 [PubMed PMID: 19450856]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence