Introduction

A corneal ulcer is a corneal epithelium defect involving the underlying stroma and is potentially a vision-threatening ocular emergency.[1] It is usually associated with tissue excavation, infiltration, and necrosis. Even with prompt treatment, patients can suffer significant morbidity with complications, including corneal scarring or perforation, development of glaucoma, cataracts or anterior and posterior synechiae, and vision loss. Untreated bacterial keratitis may result in endophthalmitis and subsequent loss of the eye.[2] The annual incidence of corneal ulcers in the United States alone is estimated to be between 30,000 and 75,000, and 12.2% of all corneal transplants performed are for managing infectious keratitis.[3][4] This condition must be recognized quickly so prompt treatment can be initiated, and emergent ophthalmologic evaluation be arranged.

The cornea contains 6 layers: the epithelium, Bowman’s membrane, the stroma, Dua’s layer, Descemet’s membrane, and the endothelium.[5] The corneal ulcer is classified based on the etiology, based on the location, and based on the involvement of corneal layers. The etiology can be due to infective causes, which include bacterial, viral, fungal, pythium, and protozoal, and noninfective causes, which include neurotrophic, neuroparalytic, vitamin A deficiency, or Mooren’s ulcer. The ulcer can be located centrally, paracentrally, or peripherally and can be superficial or deep.[6]

The common predisposing factors for corneal ulcers include ocular trauma, dry eyes, vitamin A deficiency, chronic dacryocystitis, ectropion or entropion, trichiasis, distichiasis, exophthalmos, lagophthalmos, contact lens wear, and irregular or prolonged use of corticosteroids. The systemic risk factors include malnourishment, diabetes mellitus, alcoholism, drug addiction, malignancy, acquired immune deficiency syndrome, and immunosuppression. The risk for noninfective corneal ulcers is elevated in patients with autoimmune pathologies and immunosuppression. The primary risk factor for infective keratitis is prolonged use of contact lens, cleaning contact lens with tap water, contamination, negligent wearing, and using contaminated contact lens solutions. An infective corneal ulcer is a vision-threatening keratitis with a compromised ocular surface and is an ocular emergency.[7]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Bacterial: The most common etiology of corneal ulcers is infectious, with bacterial pathogens responsible for most cases.[8] Ulcers start as keratitis (inflammation of the cornea) after a break in the corneal epithelium allows bacterial entry. These breaks most commonly occur due to contact lens wear, corneal abrasions, and other ocular trauma.[8] Other risk factors include diabetes, prior ocular surgery, chronic ocular disease, use of corticosteroids, contaminated ocular medications, and agricultural work.[9] The most common bacterial pathogens include Staphylococcus aureus, coagulase-negative staphylococcus, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa.[9] Staphylococcus epidermidis and Staphylococcus fusarium are the most commonly implicated species in polymicrobial keratitis, with trauma being the most common inciting factor.[2] The other causative organisms include Staphylococcus pyogenes and Staphylococcus pneumoniae.

Viral: Herpes simplex virus (HSV) is a common cause of viral keratitis and the most common cause of unilateral infectious corneal blindness in the developed world.[10] Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) and cytomegalovirus can also cause viral keratitis, although these are much less common. HSV-1 is more commonly implicated.

Fungal: Fungal etiologies account for only 5% to 10% of all corneal infections. They are more common in warmer, humid parts of the country and are most often precipitated by trauma to the cornea with subsequent exposure to plant or vegetable material.[8] The most commonly implicated species organisms include Aspergillus, Fusarium, Scedosporium apiospermum, phaeohyphomycetes, Candida albicans, and other Candida species.[11]

Protozoan: Acanthamoeba is a free-living protozoan found in freshwater and soil that can cause keratitis and corneal ulcers, primarily in contact lens wearers.[8]

Pythium: Pythium keratitis is a recent vision-threatening keratitis caused by the oomycete protozoan Pythium insidiosum. The species is highly virulent and causes severe vision-threatening sequelae.[12][13][14][15]

Autoimmune disease: While most corneal ulcers are infectious, it is also important to recognize noninfectious causes of corneal ulcers. Peripheral ulcerative keratitis (PUK) is a form of noninfectious keratitis associated with many systemic diseases. After anterior uveitis, PUK is the second most common ocular complication of autoimmune disorders.[16] Collagen vascular diseases account for 50% of all peripheral ulcerative keratitis cases, with rheumatoid arthritis most commonly implicated.[17] Peripheral ulcerative keratitis is also associated with Wegener granulomatosis, relapsing polychondritis, polyarteritis nodosa, Churg-Strauss syndrome, and microscopic polyangiitis.[17]

Epidemiology

Keratitis, the precursor to corneal ulceration, is responsible for approximately one million clinic and emergency department visits annually in the United States.[18] Corneal ulcers affect all groups but are much more common in those who wear contact lenses, especially extended-wear lenses. A retrospective chart review from California found the highest rate of bacterial corneal ulcers was in females aged 25 to 34 (incidence of 60.3 per 100000 person-years).[19] Estimates of the incidence of ocular herpes infection run from 5 to 20 cases per 10000 per year in developed countries. The cause of these infections is HSV-1 in over 95% of cases. Only 1.3% to 12% of cases are bilateral, and these infections tend to occur in younger patients and be more severe.[20]

Fungal keratitis is rare but more common in young male outdoor workers. Fungal keratitis is also more common in the developing world, and incidence varies widely with climate.[11] In the UK, a study found the incidence of mycotic keratitis to be 0.32 cases per million person-years. However, fungal keratitis may account for up to 50% of all infectious keratitis cases in tropical and subtropical environments.[11] Peripheral ulcerative keratitis, presenting either as an isolated condition or as part of an underlying autoimmune disorder, has an estimated incidence of 3 per million per year.[21]

Pathophysiology

The primary ocular defense mechanism includes the corneal epithelium (a mechanical barrier), the conjunctiva (a cellular and chemical barrier), and tear films, which act as biological protective systems.

The barrier to developing a corneal ulcer can be divided into anatomical, antimicrobial, and mechanical.

Anatomical Barriers

- Bony orbital rim

- Eyelids

- Conjunctival epithelium

- Corneal epithelium [22]

Mechanical

- Tear film- particularly the mucus layer

- Lacrimal drainage system [22]

Antimicrobial

- Conjunctiva-associated lymphoid tissue (CALT)

- Tear film components such as IgA complement, lactoferrin, lysozyme, and beta lysins [22]

When a corneal abrasion occurs, microbes adhere to the surface and undergo replication, infiltrating the stroma lamellae. As a result, they release toxins and lytic enzymes, causing further damage. When a defect occurs in the eye, polymorphonuclear neutrophils are released from the tears and limbal vessels to the affected area. This triggers the release of interleukins and cytokines, which gradually infiltrate the cornea and cause enlargement of the corneal ulcer. Additionally, there is a release of free radicals, proteolytic enzymes, and necrosis, resulting in the sloughing of the epithelium, Bowman's membrane, and stroma. This process leads to the creation of a saucer-shaped defect with elevated walls above the surface. Tissue swelling occurs, and the corneal stroma within the grey zone of infiltration imbibes fluid.[23]

History and Physical

The history should include questions about risk factors for corneal ulcers such as contact lens use (the type of lens, storage habits, hygiene, history of prolonged use, swimming or showering in lenses), prior ocular surgery, recent ocular trauma, personal history or exposure to herpes, work exposures, and use of immunosuppressant medications.[24] Other important points in history include the quality and severity of pain, the rapidity of onset, and the presence or absence of any photophobia or blurry vision. Patients' past medical history should be explored as diseases such as diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, and other collagen vascular diseases can predispose patients to develop corneal ulcers.[25]

The physical exam should include testing of visual acuity, intraocular pressures (if there is no concern for globe rupture or perforated ulcer), and pupillary response. The eyelids and conjunctiva should be examined for any injection, swelling, or discharge and for the presence of ciliary flush. A thorough slit-lamp examination should determine the size, location, and shape of the lesion or lesions. Seidel's test is helpful if there is any concern for rupture.

Symptoms of Bacterial Ulcer

- Pain, redness, foreign body sensation, photophobia, tearing, watery discharge, and swelling.[26]

Symptoms of Fungal Ulcer

Symptoms of Viral Ulcer

- Pain, redness, photophobia, blurred vision, gritty feeling.[29]

Evaluation

The patient with a bacterial corneal ulcer will often present with photophobia, conjunctival injection, rapid onset of pain, and a variable degree of vision loss. On slit-lamp examination, these ulcers appear as clearly defined infiltrates with stromal inflammation and edema.[8] Culture collected by an ophthalmologist is often necessary to guide treatment.

The patient with HSV keratitis or corneal ulcer usually presents similarly to those with bacterial keratitis. They will often have foreign body sensations, photophobia, conjunctival injection, and blurred vision. A slit-lamp exam will classically reveal dendritic lesions with fluorescein uptake.[8]

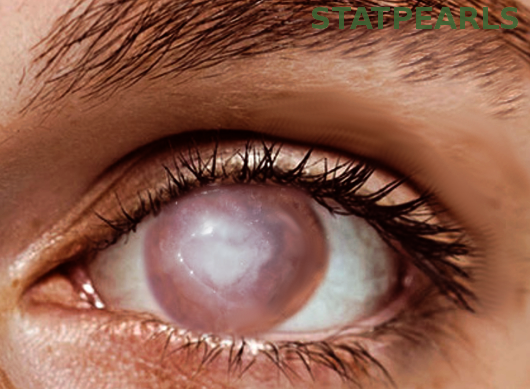

Fungal infections tend to have a more indolent course and often do not have the impressive conjunctival injection seen with bacterial infections. On slit lamp examination, fungal lesions appear as gray-white feathery dry appearing lesions with irregular margins. Ulcers due to yeast occur as superficial, white, raised colonies with clearly defined borders (see Image. Corneal Ulcer).[8]

The patient presenting with Acanthamoeba keratitis will classically present with pain out of proportion to physical exam findings. Severe photophobia is also common. The exam may reveal diffuse punctate epithelial lesions, dendritic-like lesions, or ring-shaped infiltrates.[8] Definitive diagnosis is made with direct scraping, histology, or PCR identification of Acanthamoeba DNA.[30]

Patients presenting with peripheral ulcerative keratitis (PUK) due to an underlying autoimmune disease may already carry a diagnosis, or the corneal ulcer may be the first manifestation of the disease.[17] The injury seen in PUK is usually crescent-shaped and located in the limbal region of the corneal.[16] The patient may have stigmata of their underlying disease, such as swollen and tender joints or rashes. Evaluation of these patients would include a complete ophthalmologic examination, lab work, and imaging to help diagnose or monitor the underlying autoimmune condition.

Signs of Bacterial Ulcer

Epithelial defect, corneal infiltrate, corneal abscess, melt, descemetocele, perforation, conjunctival congestion and injection, anterior chamber reaction, exudates, and hypopyon.[26]

Signs of Fungal Ulcer

Conjunctival congestion, grey or whitish stromal or full thickness infiltrate, indistinct fluffy margins, feathery margins, satellite lesions, and hypopyon.[27][28]

Signs of Viral Ulcer

Conjunctival congestion, dendritic lesion, geographical defect, subepithelial keratitis, stromal haze, edema and infiltrate, interstitial keratitis or disciform keratitis, reduced corneal sensation, corneal thinning, superficial and deep vascularization.[29]

Features of Protozoan Ulcer

The most common causative agent is Acanthamoeba castellini. The most definitive sign is perineural infiltrates or radial keratoneuritis. The other features are epithelial defect, superficial punctate keratitis, subepithelial infiltrates, stromal ulceration, limbitis, and full-thickness infiltrate.[24]

Features of Pythium Ulcer

The hallmark features of Pythium insidiosum keratitis are reticular dot infiltrates, tentacular projections, peripheral furrowing, and guttering with early limbal spread.[31][32][33][34][15]

Investigations

Bacterial Ulcer

Corneal scraping for aerobic and facultative anaerobes should employ gram staining, culture, and sensitivity with blood agar. McConkey agar, thioglycolate broth, and chocolate agar should be used for aerobic and anaerobic bacteria, including Haemophilus, Neisseria, and Moraxella. Sabouraud dextrose agar and brain heart infusion broth help culture Nocardia. Middlebrook Cohn agar can be used for Mycobacteria and Nocardia. Cooked meat broth can help culture anaerobic bacteria. Thayer-Martin medium should be employed for Neisseria and Lowenstein-Jensen medium for Mycobacterium.

Other investigations in bacterial ulcers include cultures of the conjunctival swab, contact lens culture, antibiotic sensitivity report, paracentesis, corneal biopsy, ultrasound B scan after therapeutic keratoplasty, immunohistochemistry, enzyme immunoassay, polymerase chain reaction, and radioimmunoassay.

Fungal Ulcer

Corneal scraping for 10% KOH, Giemsa stain, Gomori methenamine silver, culture and sensitivity with blood agar, thioglycollate broth, brain heart infusion broth, potato dextrose agar, and Saboruad dextrose agar can all help identify fungal causes of corneal ulcers. Corneal biopsy, polymerase chain reaction, anterior segment optical coherence tomography (AS-OCT), confocal microscopy, and ultrasound B scan can also be employed.

Viral Ulcer

Scraping with Giemsa stain or Tzanck smear and polymerase chain reaction, ELISA, viral culture, and HSV antibody titers have demonstrated usefulness.[35]

Protozoal Ulcer

Scraping with Gram stain, Calcofluor white stain, and Giemsa stain and culture on non-nutrient agar seeded with E. coli can be employed.[36]

Treatment / Management

Treatment of bacterial keratitis and corneal ulcers consists of topical antibiotics initially, most commonly fluoroquinolones such as ciprofloxacin or ofloxacin.[10] Due to the growing antibiotic resistance of common ocular pathogens, corneal culture and sensitivity testing are recommended for all corneal ulcers, especially those that are large, centrally located, and correlate with significant stromal involvement. An ophthalmologist should perform a culture of the corneal ulcer. Hospitalization for intravenous ceftriaxone therapy, as well as topical antibiotics, is necessary for ulcers caused by gonococcus. Systemic antibiotics may also be necessary for severe infections caused by the more common bacterial pathogens. Hospital admission should also be a consideration for those unable or unwilling to comply with treatment. Adjuvant corticosteroid use is controversial but may benefit specific subgroups of patients with culture-positive non-Nocardia bacterial keratitis and low vision or central ulcers covering the central 4mm of the pupil.[37][38] The treating ophthalmologist should decide whether to use adjuvant corticosteroids.(A1)

Treatment for HSV includes topical antivirals and adjuvant topical steroids. In the US, the most common topical antiviral is trifluridine, while in Europe, topical acyclovir is the first line. Other options include ganciclovir, which also treats VZV and CMV keratitis. Oral acyclovir or valacyclovir are additional options. Oral valganciclovir is the treatment of choice for CMV stromal keratitis, but the patient requires close monitoring while on this medication due to significant side effects such as aplastic anemia.[10]

Fungal ulcers tend to have worse outcomes than bacterial as there are fewer treatment options. The primary treatment is natamycin, a topical polyene first introduced in the 1960s. Amphotericin B 0.3% to 0.5% is an alternative, but toxicity limits use. A newer generation triazole called voriconazole was recently found to be inferior to natamycin in the Mycotic Ulcer Treatment Trial (MUTT I).[39] (A1)

Treatment of Acanthamoeba keratitis and corneal ulcers generally involves epithelial debridement and 3 to 4 months of antiamoebic therapy.[8] Antiamoebic therapy starts with chlorhexidine and poligexametilen biguanide, which are effective against trophozoites and cysts. Additional agents such as diamidines, fluconazole, itraconazole, neomycin, and iodine-containing medications may be supplemented for severe cases.[40]

Peripheral ulcerative keratitis associated with autoimmune and collagen vascular diseases should be treated with systemic immunosuppressants and cytotoxic agents and requires co-management by a rheumatologist and ophthalmologist.[17] These patients need careful monitoring and frequent bloodwork while on these immunosuppressant medications.(B3)

An ophthalmologist should see all patients with corneal ulcers within 12 to 24 hours. Emergent ophthalmologic consultation should be considered for a culture of the ulcer to guide antibiotic selection for suspected bacterial ulcers.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for the patient presenting with red, painful eyes includes:

- Conjunctivitis

- Corneal abrasions

- Nonulcerative keratitis

- Foreign body

- Exposure keratitis

- Iritis

- Acute angle-closure glaucoma

- Chemical burns

- Thermal burns

- Atopic keratoconjunctivitis

- Rosacea keratitis

- Shield ulcer

- Keratitis medicamentosa

- Episcleritis

- Scleritis

- Anterior uveitis [9]

Staging

Jones Criteria for Corneal Ulceration

- Mild Ulcer: The size of the ulcer is less than 2 mm, the depth is less than 20%, the infiltrate level is superficial, and the sclera is not involved.

- Moderate Ulcer: The size of the ulcer is 2 to 5 mm, the depth is 20% to 50%, the infiltrate level includes the mid-stroma, and the sclera is not involved.

- Severe Ulcer: The size of the ulcer is more than 5 mm, the depth is more than 50%, the infiltrate level is up to mid-stroma, and the sclera may be involved.[26]

Prognosis

The prognosis depends on the etiology, size, and location of the ulcer, as well as the response to treatment. Other factors that affect the prognosis are the severity of the ulcer, overall eye health, immune status, timing and compliance with treatment, socioeconomic status of the patient, complications, and individual variability. In general, superficial ulcers have a better prognosis compared to deep ulcers.

Complications

Complications of untreated or inadequately treated corneal ulcers include corneal scarring, vascularization, perforation, glaucoma, irregular astigmatism, cataracts, endophthalmitis, and vision loss.[41]

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Postoperative and rehabilitative care after keratoplasty is crucial for successful anatomical and functional outcomes. Therapeutic keratoplasty is a surgical procedure that involves replacing a damaged or diseased cornea with a healthy donor cornea to improve vision and alleviate pain or discomfort. After the surgery, the patient is taken to a recovery area where the eye will be monitored for any complications or signs of infection. The eye may be patched temporarily for protection. Topical drops or ointments are prescribed to prevent infection, reduce inflammation, and promote. Following the prescribed medication schedule diligently is crucial. Regular follow-up visits with the ophthalmologist are essential to monitor the healing progress, check for any signs of rejection, and adjust medications if needed. Wearing an eye shield or glasses with protective lenses can prevent accidental trauma to the eye during the early stages of healing.[5]

Patients must avoid touching or rubbing their eyes to prevent dislodging of the donor cornea and reduce the risk of infection. Strenuous activities, swimming, and any activities that may expose the eye to dust, dirt, or potential injury should be avoided during the initial healing period. Keeping the eye clean and avoiding irritant exposure is essential for a smooth recovery. Patients should carefully follow all the instructions provided by their ophthalmologist regarding medication, eye care, and activity restrictions. Vision rehabilitation may be necessary to optimize visual outcomes after the eye has healed. This may include vision therapy or using corrective lenses to improve vision. Patients should be aware of the signs of corneal rejection, which may include increased pain, redness, sensitivity to light, and decreased vision. If any of these symptoms occur, immediate medical attention is necessary. Educating the patient and their family about the importance of adhering to the postoperative care plan and recognizing any signs of complications is essential. Coping with the recovery process can be challenging for some patients. Providing emotional support and encouragement can help improve their overall experience. Remember that each patient's recovery may vary, and it is essential to follow instructions provided by an ophthalmologist closely. Regular communication with the healthcare team ensures the best outcome after therapeutic keratoplasty.[42]

Consultations

Any patient presenting to the routine OPD with pain, redness, photophobia, watering, and defective vision should be immediately examined on a slit lamp for a proper diagnosis and decide on the treatment. In case of corneal ulceration, the patient should be referred to an Ophthalmologist or a Corneal specialist to manage the ulcer. In cases with secondary glaucoma, the help of glaucoma specialists should be obtained.[43]

Deterrence and Patient Education

The most significant risk factor for corneal ulcers is contact lens use. Therefore, patient education about proper use is one of the most important aspects of prevention of these ulcers.[44] Patient education should include instruction on how to properly insert, clean, and store contact lenses as well as the importance of avoiding overnight or prolonged use. Patients should receive education about the dangers of swimming/showering in contacts and of purchasing contacts from nonmedical sources as well as the increased risk of infection with extended wear lenses.

Pearls and Other Issues

Corneal ulcers are a breach in the corneal epithelium associated with infiltration and necrosis. The causative factors can be infections, trauma, dry eyes, contact lens wear, or underlying medical conditions. Early diagnosis and treatment are crucial for corneal ulcers to prevent complications and potential vision loss. If the patient experiences symptoms like eye pain, redness, tearing, sensitivity to light, or blurred vision, seek immediate medical attention from an Ophthalmologist. It's essential not to self-medicate with over-the-counter eye drops or ointments without consulting an eye doctor. Inappropriate use of medications can worsen the condition and lead to complications. Corneal ulcers can be caused by different microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi, or viruses. The treatment may vary depending on the causative agent, so identifying the type of infection is essential for appropriate management. In severe or non-responsive cases, the Ophthalmologist may perform a culture and sensitivity test on a sample of the ulcer to identify the exact microorganism and determine which medications it is sensitive to.[45]

This helps in choosing the most effective antibiotic or antifungal treatment. In some cases, such as viral or fungal ulcers, using steroids can be detrimental and may exacerbate the condition. Steroids should be used with caution and under the supervision of an eye care professional. In certain cases, the Ophthalmologist may place a bandage contact lens on the eye to protect the ulcer and promote healing. However, this should be done with careful consideration, as it may not be suitable for all types of ulcers. Corneal ulcers often require frequent follow-up visits to monitor the healing progress and ensure that the treatment is effective. Compliance with the prescribed treatment plan is vital for a successful outcome. If you wear contact lenses, it's crucial to follow proper hygiene practices and care instructions. Avoid wearing lenses while you have an eye infection or corneal ulcer. To reduce the risk of corneal ulcers, practice good hygiene, avoid rubbing your eyes excessively, and protect your eyes from potential injuries by using safety goggles when appropriate. It's important to emphasize that any issues related to corneal ulcers should be managed by a qualified eye care professional. Early intervention and appropriate treatment can help minimize complications and promote optimal recovery.[46]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Corneal ulcers are a vision-threatening ocular emergency. It is imperative that healthcare providers across specialties work together so that these patients may have the best possible outcome and avoid the many potential complications. The patient will often first present in a clinic or emergency department setting and so primary care, and emergency health care professionals must be able to rapidly identify this disease and communicate effectively with their ophthalmology colleagues. Pharmacists should be consulted to help with antimicrobial selection or, in the case of peripheral ulcerative keratitis, immunosuppressants. Nurses are essential for successful treatment plans and patient education.[47]

Media

References

Ahmed F, House RJ, Feldman BH. Corneal Abrasions and Corneal Foreign Bodies. Primary care. 2015 Sep:42(3):363-75. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2015.05.004. Epub 2015 Jul 31 [PubMed PMID: 26319343]

Lin A, Rhee MK, Akpek EK, Amescua G, Farid M, Garcia-Ferrer FJ, Varu DM, Musch DC, Dunn SP, Mah FS, American Academy of Ophthalmology Preferred Practice Pattern Cornea and External Disease Panel. Bacterial Keratitis Preferred Practice Pattern®. Ophthalmology. 2019 Jan:126(1):P1-P55. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2018.10.018. Epub 2018 Oct 23 [PubMed PMID: 30366799]

Pepose JS, Wilhelmus KR. Divergent approaches to the management of corneal ulcers. American journal of ophthalmology. 1992 Nov 15:114(5):630-2 [PubMed PMID: 1443028]

Sharma S. Keratitis. Bioscience reports. 2001 Aug:21(4):419-44 [PubMed PMID: 11900320]

Gurnani B, Kaur K. Therapeutic Keratoplasty. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 37276297]

Gurnani B, Kaur K. Predicting Prognosis Based on Regional Prevalence, Ulcer Morphology and Treatment Strategy in Vision-Threatening Pythium insidiosum Keratitis. Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, N.Z.). 2023:17():1307-1314. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S412274. Epub 2023 May 5 [PubMed PMID: 37181081]

Gurnani B, Kaur K. Comment on: Online survey on practice patterns in the treatment of corneal ulcer during COVID-19 pandemic. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2022 Apr:70(4):1436-1437. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_3153_21. Epub [PubMed PMID: 35326080]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFarahani M, Patel R, Dwarakanathan S. Infectious corneal ulcers. Disease-a-month : DM. 2017 Feb:63(2):33-37. doi: 10.1016/j.disamonth.2016.09.003. Epub 2016 Dec 22 [PubMed PMID: 28017285]

Gilani CJ, Yang A, Yonkers M, Boysen-Osborn M. Differentiating Urgent and Emergent Causes of Acute Red Eye for the Emergency Physician. The western journal of emergency medicine. 2017 Apr:18(3):509-517. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2016.12.31798. Epub 2017 Mar 3 [PubMed PMID: 28435504]

Austin A, Lietman T, Rose-Nussbaumer J. Update on the Management of Infectious Keratitis. Ophthalmology. 2017 Nov:124(11):1678-1689. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.05.012. Epub 2017 Sep 21 [PubMed PMID: 28942073]

Thomas PA, Kaliamurthy J. Mycotic keratitis: epidemiology, diagnosis and management. Clinical microbiology and infection : the official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. 2013 Mar:19(3):210-20. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12126. Epub 2013 Feb 9 [PubMed PMID: 23398543]

Gurnani B, Kaur K, Tandon A. Letter Regarding: Randomized Double-Masked Placebo-Controlled Trial for the Management of Pythium Keratitis: Combination of Antibiotics Versus Monotherapy. Cornea. 2023 Dec 1:42(12):e22-e23. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000003350. Epub 2023 Jul 18 [PubMed PMID: 37487172]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGurnani B, Kaur K, Kumar T. Commentary: Current concepts, recent updates, and future treatment options for Pythium insidiosum keratitis. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2023 May:71(5):1874-1876. doi: 10.4103/IJO.IJO_80_23. Epub [PubMed PMID: 37203047]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGurnani B, Kaur K. Pythium Keratitis. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 34424645]

Gurnani B, Christy J, Kaur K, Moutappa F, Gubert J. Successful Management of Pythium insidiosum Keratitis Masquerading as Dematiaceous Fungal Keratitis in an Immunosuppressed Asian Male. Ocular immunology and inflammation. 2023 Feb 22:():1-4. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2023.2179495. Epub 2023 Feb 22 [PubMed PMID: 36812410]

Cao Y, Zhang W, Wu J, Zhang H, Zhou H. Peripheral Ulcerative Keratitis Associated with Autoimmune Disease: Pathogenesis and Treatment. Journal of ophthalmology. 2017:2017():7298026. doi: 10.1155/2017/7298026. Epub 2017 Jul 13 [PubMed PMID: 28785483]

Ladas JG, Mondino BJ. Systemic disorders associated with peripheral corneal ulceration. Current opinion in ophthalmology. 2000 Dec:11(6):468-71 [PubMed PMID: 11141643]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCope JR, Collier SA, Srinivasan K, Abliz E, Myers A, Millin CJ, Miller A, MS, Tarver ME. Contact Lens-Related Corneal Infections - United States, 2005-2015. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2016 Aug 19:65(32):817-20. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6532a2. Epub 2016 Aug 19 [PubMed PMID: 27538244]

Jeng BH, Gritz DC, Kumar AB, Holsclaw DS, Porco TC, Smith SD, Whitcher JP, Margolis TP, Wong IG. Epidemiology of ulcerative keratitis in Northern California. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 2010 Aug:128(8):1022-8. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.144. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20697003]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHill GM, Ku ES, Dwarakanathan S. Herpes simplex keratitis. Disease-a-month : DM. 2014 Jun:60(6):239-46. doi: 10.1016/j.disamonth.2014.03.003. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24906668]

Galor A, Thorne JE. Scleritis and peripheral ulcerative keratitis. Rheumatic diseases clinics of North America. 2007 Nov:33(4):835-54, vii [PubMed PMID: 18037120]

Pearlman E, Sun Y, Roy S, Karmakar M, Hise AG, Szczotka-Flynn L, Ghannoum M, Chinnery HR, McMenamin PG, Rietsch A. Host defense at the ocular surface. International reviews of immunology. 2013 Feb:32(1):4-18. doi: 10.3109/08830185.2012.749400. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23360155]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGurnani B, Christy J, Narayana S, Kaur K, Moutappa F. Corneal Perforation Secondary to Rosacea Keratitis Managed with Excellent Visual Outcome. Nepalese journal of ophthalmology : a biannual peer-reviewed academic journal of the Nepal Ophthalmic Society : NEPJOPH. 2022 Jan:14(27):162-167. doi: 10.3126/nepjoph.v14i1.36454. Epub [PubMed PMID: 35996914]

Gurnani B, Kaur K. Contact Lens–Related Complications. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 36512659]

Gurnani B, Narayana S, Christy J, Rajkumar P, Kaur K, Gubert J. Successful management of pediatric pythium insidiosum keratitis with cyanoacrylate glue, linezolid, and azithromycin: Rare case report. European journal of ophthalmology. 2022 Sep:32(5):NP87-NP91. doi: 10.1177/11206721211006564. Epub 2021 Mar 28 [PubMed PMID: 33779337]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGurnani B, Kaur K. Bacterial Keratitis. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 34662023]

Gurnani B, Kaur K. Comment on: Clinical and mycological profile of fungal keratitis from North and North-East India. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2023 Jun:71(6):2607-2608. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1655_22. Epub [PubMed PMID: 37322697]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGurnani B, Kaur K, Gurav J. Natasol as a future management option to combat fungal keratitis. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2023 May:71(5):2302-2303. doi: 10.4103/IJO.IJO_190_23. Epub [PubMed PMID: 37202986]

Ahmad B, Gurnani B, Patel BC. Herpes Simplex Keratitis. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31424862]

Bouheraoua N, Labbé A, Chaumeil C, Liang Q, Laroche L, Borderie V. [Acanthamoeba keratitis]. Journal francais d'ophtalmologie. 2014 Oct:37(8):640-52. doi: 10.1016/j.jfo.2014.05.004. Epub 2014 Aug 29 [PubMed PMID: 25169145]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGurnani B, Christy J, Narayana S, Rajkumar P, Kaur K, Gubert J. Retrospective multifactorial analysis of Pythium keratitis and review of literature. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2021 May:69(5):1095-1101. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1808_20. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33913840]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGurnani B, Kaur K, Venugopal A, Srinivasan B, Bagga B, Iyer G, Christy J, Prajna L, Vanathi M, Garg P, Narayana S, Agarwal S, Sahu S. Pythium insidiosum keratitis - A review. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2022 Apr:70(4):1107-1120. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1534_21. Epub [PubMed PMID: 35325996]

Gurnani B, Kaur K. Comment on: Sensitivity and specificity of potassium hydroxide and calcofluor white stain to differentiate between fungal and Pythium filaments in corneal scrapings from patients of Pythium keratitis. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2022 Jun:70(6):2204. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_345_22. Epub [PubMed PMID: 35648022]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGurnani B, Kaur K, Agarwal S, Lalgudi VG, Shekhawat NS, Venugopal A, Tripathy K, Srinivasan B, Iyer G, Gubert J. Pythium insidiosum Keratitis: Past, Present, and Future. Ophthalmology and therapy. 2022 Oct:11(5):1629-1653. doi: 10.1007/s40123-022-00542-7. Epub 2022 Jul 5 [PubMed PMID: 35788551]

Koganti R, Yadavalli T, Naqvi RA, Shukla D, Naqvi AR. Pathobiology and treatment of viral keratitis. Experimental eye research. 2021 Apr:205():108483. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2021.108483. Epub 2021 Feb 6 [PubMed PMID: 33556334]

Pestechian N, Tavakoli S, Adibi P, Safa AH, Parsaei R, Yousefi HA. Prevalence of Intestinal Protozoan Infection in Patients with Ulcerative Colitis (UC) in Isfahan, Iran. International journal of preventive medicine. 2021:12():114. doi: 10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_471_19. Epub 2021 Sep 21 [PubMed PMID: 34760125]

Al-Mujaini A, Al-Kharusi N, Thakral A, Wali UK. Bacterial keratitis: perspective on epidemiology, clinico-pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. Sultan Qaboos University medical journal. 2009 Aug:9(2):184-95 [PubMed PMID: 21509299]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSrinivasan M, Mascarenhas J, Rajaraman R, Ravindran M, Lalitha P, O'Brien KS, Glidden DV, Ray KJ, Oldenburg CE, Zegans ME, Whitcher JP, McLeod SD, Porco TC, Lietman TM, Acharya NR, Steroids for Corneal Ulcers Trial Group. The steroids for corneal ulcers trial (SCUT): secondary 12-month clinical outcomes of a randomized controlled trial. American journal of ophthalmology. 2014 Feb:157(2):327-333.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2013.09.025. Epub 2013 Oct 1 [PubMed PMID: 24315294]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencePrajna NV, Krishnan T, Mascarenhas J, Rajaraman R, Prajna L, Srinivasan M, Raghavan A, Oldenburg CE, Ray KJ, Zegans ME, McLeod SD, Porco TC, Acharya NR, Lietman TM, Mycotic Ulcer Treatment Trial Group. The mycotic ulcer treatment trial: a randomized trial comparing natamycin vs voriconazole. JAMA ophthalmology. 2013 Apr:131(4):422-9 [PubMed PMID: 23710492]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMarchenko NR, Kasparova EA. [Treatment of Acanthamoeba keratitis]. Vestnik oftalmologii. 2016:132(5):110-116. doi: 10.17116/oftalma20161325110-116. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28635735]

AlMahmoud T, Elhanan M, Elshamsy MH, Alshamsi HN, Abu-Zidan FM. Management of infective corneal ulcers in a high-income developing country. Medicine. 2019 Dec:98(51):e18243. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000018243. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31860971]

Seewoodhary R, Stevens S. Transmission and control of infection in ophthalmic practice. Community eye health. 1999:12(30):25-8 [PubMed PMID: 17491987]

Murthy SI, Das S, Deshpande P, Kaushik S, Dave TV, Agashe P, Goel N, Soni A. Differential diagnosis of acute ocular pain: Teleophthalmology during COVID-19 pandemic - A perspective. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2020 Jul:68(7):1371-1379. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1267_20. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32587167]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLoh K, Agarwal P. Contact lens related corneal ulcer. Malaysian family physician : the official journal of the Academy of Family Physicians of Malaysia. 2010:5(1):6-8 [PubMed PMID: 25606178]

Fleiszig SMJ, Kroken AR, Nieto V, Grosser MR, Wan SJ, Metruccio MME, Evans DJ. Contact lens-related corneal infection: Intrinsic resistance and its compromise. Progress in retinal and eye research. 2020 May:76():100804. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2019.100804. Epub 2019 Nov 20 [PubMed PMID: 31756497]

McKeny PT, Nessel TA, Zito PM. Antifungal Antibiotics. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30844195]

Burrow MK, Patel BC. Keratoconjunctivitis. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31194419]