Human African Trypanosomiasis (Sleeping Sickness)

Human African Trypanosomiasis (Sleeping Sickness)

Introduction

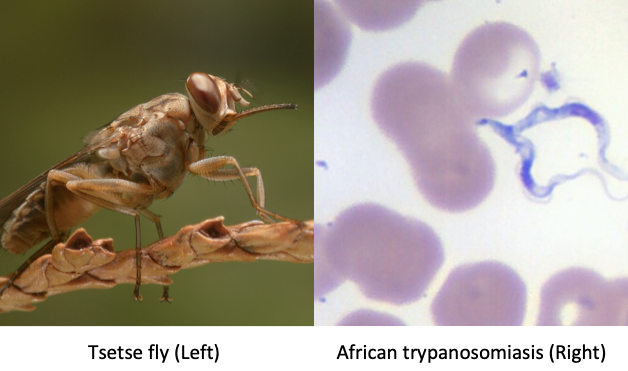

Human African trypanosomiasis (HAT), or African sleeping sickness, is a potentially life-threatening infectious illness caused by the protozoans Trypanosoma brucei gambiense (T brucei gambiense) or Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense (T brucei rhodesiense) transmitted by the tsetse fly (see Image. Vector and Organism of Human African Trypanosomiasis).[1] This disease is endemic in sub-Saharan Africa but can be seen outside of endemic areas among travelers. These parasites produce illnesses with different clinical and epidemiological characteristics. East African HAT is caused by T brucei rhodesiense. West African HAT is caused by T brucei gambiense. Both conditions have hemolymphatic and meningoencephalitic stages.[2] HAT is considered a neglected tropical disease and is a significant public health threat in rural Africa.[3]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The protozoa species T brucei gambiense and T brucei rhodesiense cause HAT. The tsetse fly (order Diptera, genus Glossina) is responsible for these organisms' human-to-human transmission. Rare vertical and transfusional transmissions have also been reported.[4]

Trypanosoma is a unicellular parasitic protozoan with a complex life cycle requiring 2 hosts. In the human host, this species' metacyclic trypomastigotes have 2 notable morphologies: a dividing, elongated, and slender form and a nonproliferating, short, and "stumpy" form. Slender trypanosomes can swim in the bloodstream or lymphatics and invade body organs, including the central nervous system (CNS). The organisms at this growth stage possess flagellae and kinetoplasts.

Transformation into the stumpy form is triggered by trypanosome cell density. After reaching an adequate parasitemia level, slender trypanosomes secrete increasing amounts of stumpy induction factor (SIF), which induces the stumpy transformation. Dependence on cell density regulates the parasite level in the host. Stumpy trypanosomes are short-lived but more capable of infecting the vector than slender parasites. Only one stumpy trypanosome is necessary to perpetuate the parasite's life cycle in the vector.

After a blood meal, the tsetse fly is infected by either stumpy or slender trypanosomes. The parasites then enter the proliferative procyclic stage. Procyclic trypanosomes may colonize the vector's gut, enter the nonproliferating mesocyclic stage, or transit in the proventriculus and transform into proliferative epimastigotes. The epimastigotes swim toward the tsetse fly's salivary glands while undergoing asymmetric cell division. The short daughter cell survives and attaches to the salivary gland epithelium via its flagellum. The long daughter cell does not survive. The surviving epimastigotes may produce either more attached, proliferating epimastigotes or nonmultiplying, freely swimming, human-infective metacyclic trypomastigotes. Thus, the parasite's life cycle goes to completion in the vector.[5]

Vector-to-mammal transmission usually occurs around 2 weeks after an infected blood meal. African trypanosomiasis or "nagana" arises when the parasite infects animals. This condition has significant agricultural implications.[6]

Epidemiology

HAT is seen in 36 countries across sub-Saharan Africa.[7] The condition has West and East African variants, distinguished based on clinical and epidemiologic attributes. The continent's Great Rift Valley sharply demarcates the geographic distributions of East and West African HAT.[8]

West African HAT arises from T brucei gambiense transmission by Glossina palpalis (G palpalis), both endemic in this region. T brucei gambiense exclusively has humans as reservoirs and causes 98% of HAT.[9] G palpalis is primarily encountered in humid areas around water sources. Thus, people who live or work near watery locations are at risk of being bitten by G palpalis.[10] West African HAT is rare in short-staying tourists and visitors but is often seen in refugees and immigrants. About 80% of West African HAT cases are found in the Democratic Republic of Congo. The World Health Organization (WHO) aims to completely disrupt West African HAT transmission by 2030.[11]

In contrast, East African HAT develops from T brucei rhodesiense transmission by Glossina morsitans (G morsitans). These species are more common in this area.[12][13] T brucei rhodesiense's main reservoirs are cattle and other mammals. This parasite mostly causes zoonotic disease, but the human disease variant can be difficult to control as it causes severe parasitemia.[14] G morsitans bacteria live mostly in dry, wooded areas. Notably, this tsetse fly species does not bite humans as frequently as other mammals. People at risk of getting bitten by this insect go into wooded areas where the flies breed or bite other mammals. T brucei rhodesiense has been detected in tourists in East Africa, mainly in Tanzania and regions with wild game parks.

East African HAT mainly occurs in Zimbabwe, Tanzania, Zambia, and Malawi, infecting primarily wild animals. In Uganda and Kenya, East African HAT mostly affects cattle.[15]

T. brucei was responsible for the late 1800s and early 1900s epidemics, killing nearly a million people. The disease was almost eradicated in the 1960s after colonial countries started early vector control and disease surveillance. Increased population and decreased surveillance led to recurrence, with a peak incidence in the late 1990s. In 1998, around 300,000 HAT cases were reported in sub-Saharan Africa. Increased screening and treatment efforts supported by Belgium, France, and the WHO led to a steady case reduction to 7000 in 2012, then fewer than 1000 cases in 2022.[16][17][18]

HAT is mainly seen in rural communities and impoverished areas. The occurrence of this condition remains underreported despite the WHO's attempts to reinstitute control programs.[19]

Pathophysiology

One of the human body's primary immune defenses against trypanosomes is apolipoprotein 1 (APOL1), a lytic serum protein factor with extracellular activity. However, T brucei rhodesiense and T brucei gambiense can resist APOL1, allowing them to infect humans. The organisms enter the bloodstream and lymphatics and induce intense inflammation.

A robust inflammatory response spreads in the CSF driven by interferon-λ (IFN-λ). Astrocyte activation, macrophage and T cell activation, and inflammatory infiltration allow the trypanosomes to cross the brain vasculature's tight junctions. The progression of the illness depends on the host's genetics and the infecting subspecies. T brucei rhodesiense infection proceeds rapidly, with severe inflammation resulting in hemolytic anemia. Death can occur within 6 months. In contrast, the disease course in T brucei gambiense infection generally takes years, with only 20% of infected people developing CNS involvement after 24 months.[18]

Histopathology

Affected patients' peripheral blood smears show wiggling trypanosomes 20 to 30 μm long. Lymph node aspirate examination may also reveal trypanosomes. Over 70% of patients have diffuse cardiac involvement. Histopathological examination may reveal trypanosomes in the pericardium, myocardium, endocardium, and interstitial space.[19]

The brain is typically grossly normal. However, histopathologic examination often shows numerous histiocytes and lymphocytosis with B-cell predominance around the blood vessels. Morular cells are plasma cells characteristic of HAT, with Russell body-filled cytoplasm and small peripheral nuclei. Large astrocytes with microglial hyperplasia are often present. Autopsies rarely show trypanosomes in brain parenchyma, but the parasites' absence does not rule out the diagnosis.[20]

History and Physical

The clinical disease has hemolymphatic and meningoencephalitis stages. The 1st stage has primarily hemolymphatic involvement, while CNS invasion characterizes the 2nd stage.

HAT’s earliest manifestation is a cutaneous chancre at the inoculation site. However, only patients with T brucei gambiense develop this lesion, and individuals with T brucei rhodesiense infrequently have the chancre. Systemic symptoms develop afterward, with intermittent fever, headache, pruritus, and lymphadenopathy. Fevers often persist from a day to a week and are separated by afebrile intervals of days to months. Undulating fevers reflect parasites multiplying in the blood.

T brucei gambiense lymphadenopathy, known as the Winterbottom sign, may be particularly conspicuous in the posterior cervical triangle. In contrast, T brucei rhodesiense lymphadenopathy is more often located in the inguinal, submandibular, and axillary regions rather than the posterior neck triangle.

Hepatosplenomegaly and endocrine dysfunction occur more commonly in first-stage T brucei rhodesiense than in T brucei gambiense disease. Endocrine dysfunction, with manifestations such as hypothyroidism, hypogonadism, and adrenal crisis, is more commonly seen in T brucei rhodesiense than in T brucei gambiense disease due to trypanosome infiltration of the endocrine organs.

CNS symptoms become prominent in the meningoencephalitis stage. Psychiatric disturbance often accompanies disordered sleep. “African sleeping sickness” was coined due to these observed symptoms. The sleep problems are further described as sleep-wake cycle dysregulation with sleep fragmentation and frequent short rapid eye movement periods. Sleep pattern inversion is present, characterized by strong daytime sleep urges and nighttime insomnia.

Other neurologic symptoms include tremors, weakness, paralysis, dyskinesia, choreoathetosis, Parkinsonian hypertonia, and abnormal reflexes. Psychiatric changes include aggression, apathy, psychosis, or irritability.

Unlike in Chagas disease caused by Trypanosoma cruzi infection, the heart is less frequently involved in T brucei gambiense infection. About half of the affected patients develop electrocardiogram abnormalities, including prolonged QTc, repolarization aberrations, PR depression, and low voltage. However, these changes are often clinically insignificant. Ventricular arrhythmias are rare. In contrast, T brucei rhodesiense may cause severe pericarditis or myopericarditis.

HAT in travelers presents differently, often manifesting with cutaneous chancres and more pronounced internal organ involvement. A transient trypanosomal rash may develop in fair-skinned individuals, characterized by erythema, pruritus, and a targetoid appearance. Infections with both subspecies have shorter incubation periods.

The clinical endpoint of either HAT form is coma followed by death if untreated. Death occurs more rapidly with T brucei rhodesiense infection, often within weeks to months. Mortality from untreated T brucei gambiense infection occurs 3 years on average after inoculation.

Evaluation

The choice of diagnostic modalities depends on the clinical phase. Peripheral blood smearing is usually enough for T brucei rhodesiense infection, which causes high-level parasitemia. In contrast, T brucei gambiense infection necessitates more sensitive screening tests as parasitemia may not be as prominent.

The card-agglutination test for trypanosomiasis (CATT) is a serologic test that may initially be used to screen suspected cases. Venipuncture or fingerstick blood may be used as samples, though CATT has higher specificity if performed on plasma or serum dilutions. This test employs T brucei gambiense antigens and has a variable sensitivity of 91%. Despite having a negative predictive value of 99%, CATT’s positive predictive value remains low in low-prevalence areas (<0.1%).[21] Thus, CATT cannot be conducted for diagnostic confirmation. Other sensitive serologic tests, such as immunofluorescence or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays, may be used as screening tools in nonendemic areas.[22]

Active disease diagnosis relies on the combination of clinical history (including a history of travel to endemic areas), direct parasite visualization, and adjunctive serologic tests. Blood, lymph node aspirate, or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) microscopic examination may yield parasites. Result interpretation highly depends on the laboratory technologist’s experience and training.[23]

Thin and thick blood films have low sensitivity. Meanwhile, miniature anion exchange and capillary tube centrifugation or buffy coat examination can increase yield. PCR may also be used if available.

CSF examination may be used to confirm Stage 2 disease in suspected patients. However, parasites may be absent in the CSF regardless of stage. For this reason, the WHO’s criteria for Stage 2 disease include having more than 5 white blood cells per μL (WBCs/μL) of CSF.

Individuals with T brucei gambiense infection should only undergo CSF evaluation if severe Stage 2 disease is suspected or patients have contraindications to fexinidazole therapy.[24] Symptoms concerning severe Stage 2 disease include confusion, abnormal behavior, nonsensical or impaired speech, ataxia, abnormal movements, muscular weakness, and seizures.[25]

In contrast, the WHO recommends CSF evaluation for stratification in patients with T brucei rhodesiense infection, which directly impacts treatment decisions. The WHO is presently creating new guidelines with the advent of fexinidazole, a medication active in both first-stage and mild second-stage disease.[26]

Treatment / Management

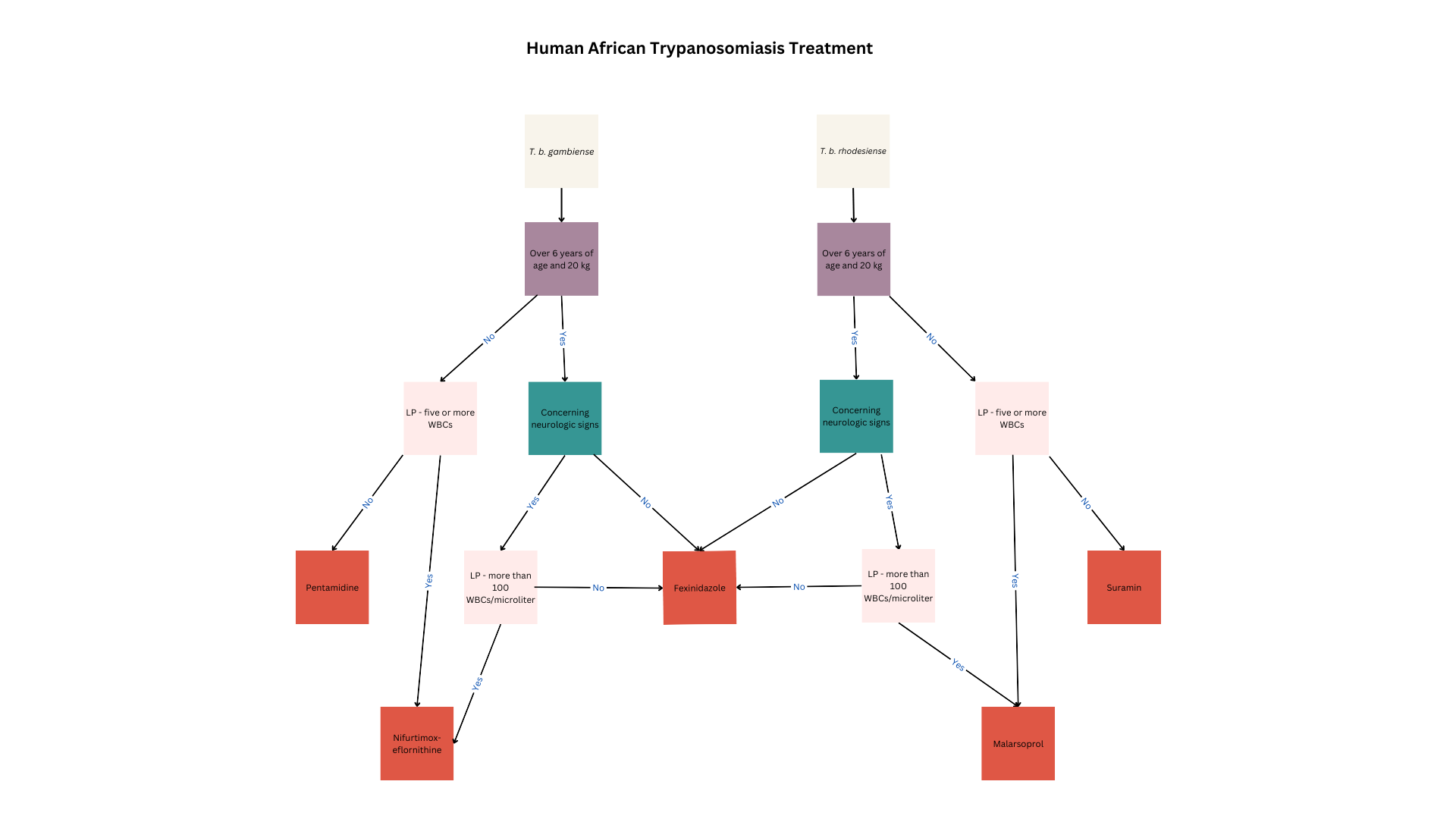

HAT treatment depends on the etiologic agent, infection stage, patient factors, and presence of contraindications (see Image. Human African Trypanosomiasis Treatment). All children, women of reproductive age, and patients in the acute illness phase or reactivation must receive treatment to limit morbidity and mortality and prevent transmission.

West African HAT Treatment

Fexinidazone is the drug of choice for T brucei gambiense treatment. This oral nitroimidazole agent is highly effective in both first- and second-stage disease except in highly advanced stages.

Stage 1 disease

Fexinidazole is the first-line therapy in patients with Stage 1 T brucei gambiense disease who are older than 6 years and weigh at least 20 kg. Oral administration makes this drug convenient in communities with limited healthcare resources. Common adverse reactions to fexinidazole include gastrointestinal disturbances such as nausea, vomiting, decreased appetite, insomnia, and tremors. This drug can cause QT prolongation and should not be used in patients with hepatic insufficiency or allergies to other nitroimidazoles.

Fexinidazole can be given in the outpatient setting if patients can eat, weigh more than 35 kg, are reliably treatment-compliant, and have no concurrent psychiatric disorders that can make medication adherence difficult. The medication is given once daily for 10 days, with a loading dose in the first 4 days. Dosage depends on body weight.

People weighing at least 35 kg require a loading dose of 1800 mg and a maintenance dose of 1200 mg. Patients weighing between 20 and 34 kg require a loading dose of 1200 mg and a maintenance dose of 600 mg. The regimen must be restarted from day 0 if a dose is missed and more than a day has passed. At least 3 maintenance doses must be taken correctly for the regimen to be considered complete.

Pentamidine may be prescribed to younger patients and people with contraindications to fexinidazole or who do not meet the treatment criteria. The preferred pentamidine regimen for HAT is 4 mg/kg via intragluteal intramuscular injection daily for 1 week on alternating body sides.

Pentamidine is ineffective in second-stage disease, as it does not cross the blood-brain barrier. Pentamidine’s side effects include injection site reactions, hypotension, and hypoglycemia. Patients should be given a beverage or food with high glucose content before pentamidine administration to prevent hypoglycemia. Patients must also be advised to lie down for 1 hour after each dose due to possible drug-induced hypotension. More serious adverse events seen with pentamidine in the treatment of other diseases include leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, hyperkalemia, and QT prolongation.

Stage 2 disease

Pharmacological treatment for second-stage T brucei gambiense disease depends on the WBC count noted on CSF examination. Fexinidazole is recommended in patients with less than 100 WBCs/μL, older than 6 years, and weighing over 20 kilograms. Meanwhile, younger individuals or people weighing less than 20 kg may be prescribed nifurtimox-eflornithine combination therapy (NECT). NECT is also recommended in patients with a WBC count of at least 100/μL in the CSF.

Nifurtimox is given at a daily dose of 15 mg/kg for 10 days, divided into 3. Eflornithine is given concomitantly at a total daily dose of 400 mg/kg intravenously for 10 days, infused over 2 hours twice daily. Eflornithine is superior in reducing mortality and less toxic than melarsoprol. Therefore, eflornithine is the preferred medication over melarsoprol for second-stage disease. Combining nifurtimox and eflornithine reduces the dosage and cost of therapy.[27] Adverse reactions to eflornithine include pancytopenia, gastrointestinal distress, headache, and seizures.(B3)

Rescue

NECT is recommended for patients younger than 6 years or weighing less than 20 kg. These patients must also have less than 5 WBCs/μL in the CSF, no CSF trypanosomes, and poor pentamidine therapeutic response. The NECT-long regimen is recommended for individuals with more than 5 WBC/μL or visible trypanosomes in the CSF who fail NECT or eflornithine therapy.

NECT is recommended for individuals who are at least 6 years old, weigh at least 20 kg, lack severe disease signs, and have failed fexinidazole therapy. NECT is likewise recommended for people suspected of having severe HAT but have less than 100 WBCs/μL in the CSF and have failed fexinidazole treatment.

NECT-long therapy is recommended for people who have at least 100 WBCs/μL in the CSF or cannot get a lumbar puncture for any reason and fail NECT therapy. Eflornithine must be extended to 14 days in the NECT-long therapy.

Melarsoprol may also be considered but avoided if possible, as it may cause encephalopathic syndrome, a fatal condition that develops in 6% of all patients treated with this medication. Melarsoprol is given at a dose of 2.2 mg/kg once daily for 10 days concurrently with prednisolone.

East African HAT Treatment

Fexinidazole is also effective against T brucei rhodesiense disease. Individuals who do not meet the criteria for fexinidazole therapy may be given suramin or melarsoprol.

Stage 1 disease

First-stage T brucei rhodesiense disease in patients at least 6 years old and weighing at least 20 kg is treated with fexinidazole as above. Patients with contraindications to fexinidazole should be treated with suramin.

Suramin is also effective against T brucei gambiense. However, the high Onchocerca prevalence in T brucei rhodesiense–endemic areas and the risk of severe drug-induced allergy prohibits suramin use in West and Central Africa. For first-stage T brucei rhodesiense disease, the initial dose tests for hypersensitivity. Afterward, 5 mg/kg of suramin is injected intravenously once weekly for 5 weeks. Notably, this medication rapidly degrades on air exposure and thus needs to be injected immediately after dilution with distilled water. Adverse reactions to suramin besides hypersensitivity include nephrotoxicity, peripheral neuropathy, and bone marrow toxicity with subsequent agranulocytosis and thrombocytopenia.

Stage 2 disease

Patients who have second-stage T brucei rhodesiense disease, are at least 6 years old, weigh at least 20 kg, and have less than 100 WBCs/μL in CSF should be treated with fexinidazole.[28] Individuals who have contraindications to fexinidazole or do not fit these criteria may be treated with melarsoprol. (B3)

Adverse reactions to melarsoprol may be severe. Encephalopathic syndrome occurs in up to 18% of patients. Patients may be given dexamethasone and diazepam for encephalopathic syndrome treatment, but the fatality rate from this condition is still quite high. Skin reactions, including pruritus and maculopapular rashes, are common. Bullous lesions can occur, though rarely. Motor and sensory neuropathies may also develop.

Follow-up

Patients treated with a fexinidazole regimen should have evaluations at 6, 12, 18, and 24 months to assess for disease relapse. The blood and CSF must be reexamined if concerning symptoms are present.

In the first 4 months after completing therapy, the only rescue treatment indication is the presence of trypanosomes in the blood or CSF. From 5 to 9 months posttreatment, finding at least 50 WBCs/μL in the CSF is an indication for rescue therapy.

At 12 months, finding 6-49 WBCs/μL in the CSF should prompt careful evaluation for relapse. Rescue therapy should only be given if symptoms strongly suggest relapse. From 10 to 24 months, rescue therapy may given for CSF WBCs of at least 20/μL. Patients treated with other regimens do not need close follow-up after treatment, as efficacy is very high.

Differential Diagnosis

Relapsing fevers may be seen in multiple diseases and are often indicative of parasitemia. Some parasitic infections are listed below. A history of staying in endemic areas, a lack of bleeding diathesis, and the presence of encephalopathy in the late stages distinguish African trypanosomiasis from these diseases.

- Malaria

- Typhoid fever

- Viral hepatitis

- Ehrlichiosis

- Dengue

- Brucellosis

- Babesiosis

- Yellow fever

Cutaneous trypanosomiasis manifestations may appear nonspecific and be confused with the following conditions:

- Drug rash

- Boutenneuse fever-associated eschar

- Arthropod bite hypersensitivity reaction

Prognosis

Over 95% of patients with first- and second-stage T brucei gambiense disease are definitively cured with proper treatment. Meanwhile, individuals with second-stage T brucei rhodesiense disease have a 5% to 10% mortality risk during or after melarsoprol therapy. Early treatment can dramatically reduce mortality rates, but a diagnostic delay may be fatal. The prognosis of untreated HAT is dismal, with death being invariable. Mortality was higher when melarsoprol was the only therapeutic option, with 4% to 12% of deaths occurring from the treatment rather than the illness. However, the European Medicines Agency’s approval of fexinidazole for use in T brucei rhodesiense disease decreased malarsoprol use.

Complications

Most people treated for first-stage HAT do not experience complications after therapy. However, second-stage HAT survivors may report lasting neurologic issues. A study revealed that 12 to 13 years after second-stage HAT treatment, 7.8% complained of nighttime sleep difficulties, while 3.9% reported daytime sleep problems. Headaches were noted in 11% of patients. Speech difficulties, muscle weakness, and personality changes steadily decreased after treatment, with no increased risk seen at the 12th- to 13th-year follow-up.[29]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Control programs in endemic areas are paramount to lowering HAT cases. Active screening campaigns, ie, mobile teams screening populations in endemic areas, interrupt T. brucei’s life cycle and reduce cases. A vaccine is currently unavailable.

Inhabitants and travelers to endemic areas should avoid areas where tsetse flies breed or are frequently seen. Wearing long sleeves and pants and using insecticide-treated nets can reduce the risk of tsetse fly bites. Treating cattle with insecticide may help contain T brucei rhodesiense outbreaks.

Pearls and Other Issues

The most important points to remember in evaluating and managing HAT are the following:

- HAT is an endemic disease in sub-Saharan Africa. Control measures implemented in the 1960s lapsed, leading to a resurgence in the 1990s. The WHO currently classifies the condition as a neglected disease.

- T brucei gambiense and T brucei rhodesiense are HAT’s etiologic agents, producing disease variants with distinct geographic profiles and clinical courses. T brucei gambiense is responsible for West African HAT, a chronic, protracted fatal disease in West and Central Africa. Meanwhile, T brucei rhodesiense causes the rapidly fatal East African variant in East and Central sub-Saharan Africa.

- Diagnosing human African trypanosomiasis depends on clinical history, serologic testing, and confirmation by direct parasite visualization.

- Fexinidazole is the treatment of choice unless patients do not meet the treatment criteria or have contraindications to the drug. Alternatives include nifurtimox, eflornithine, suramin, and melarsoprol.

- Prompt treatment has a good prognosis. Lack of treatment is invariably fatal.

- Relapse can occur months after treatment, necessitating reevaluation and rescue therapy.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Currently, no vaccine has been developed for HAT. Nevertheless, community engagement and concerted efforts from health authorities have proven effective in controlling and potentially eliminating the disease, as observed in past initiatives spearheaded by colonial territories and the WHO. A crucial component of this endeavor lies in the cooperation extended by local governments in endemic regions, facilitating the implementation of screening and treatment programs while ensuring accurate reporting of new cases. The meticulous documentation of cases by local healthcare facilities and personnel significantly enhances the efficacy of evaluation and treatment strategies.

The success of treatment interventions is paramount, given the potentially fatal consequences of untreated HAT. Optimal outcomes hinge upon the collaborative efforts of an interprofessional healthcare team comprising infectious disease specialists, neurologists, critical care physicians, pharmacists, and nursing personnel. Comprehensive medical outreach endeavors involving interprofessional teams hold considerable promise in enhancing public health outcomes. These initiatives can enhance communities' education about the importance of HAT screening, prompt treatment, and therapeutic adherence, thereby fostering improved disease management and prevention efforts.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Vector and Organism of Human African Trypanosomiasis Left: Attributed To: This image was contributed by the International Atomic Energy Agency - International Atomic Energy Agency This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Glossinidae#/media/File:Tsetse-BKF-2.jpg Right: Imported case in an American who brought it back from a hunting trip in Gambia. Photo by Margaret Uthman, MD. Pathological and histological images courtesy of Ed Uthman at Flickr.

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Sutherland CS, Yukich J, Goeree R, Tediosi F. A literature review of economic evaluations for a neglected tropical disease: human African trypanosomiasis ("sleeping sickness"). PLoS neglected tropical diseases. 2015 Feb:9(2):e0003397. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003397. Epub 2015 Feb 5 [PubMed PMID: 25654605]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBüscher P, Cecchi G, Jamonneau V, Priotto G. Human African trypanosomiasis. Lancet (London, England). 2017 Nov 25:390(10110):2397-2409. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31510-6. Epub 2017 Jun 30 [PubMed PMID: 28673422]

Stich A, Abel PM, Krishna S. Human African trypanosomiasis. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2002 Jul 27:325(7357):203-6 [PubMed PMID: 12142311]

Brun R, Blum J, Chappuis F, Burri C. Human African trypanosomiasis. Lancet (London, England). 2010 Jan 9:375(9709):148-59. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60829-1. Epub 2009 Oct 14 [PubMed PMID: 19833383]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSchuster S, Lisack J, Subota I, Zimmermann H, Reuter C, Mueller T, Morriswood B, Engstler M. Unexpected plasticity in the life cycle of Trypanosoma brucei. eLife. 2021 Aug 6:10():. doi: 10.7554/eLife.66028. Epub 2021 Aug 6 [PubMed PMID: 34355698]

Matthews KR. The developmental cell biology of Trypanosoma brucei. Journal of cell science. 2005 Jan 15:118(Pt 2):283-90 [PubMed PMID: 15654017]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKennedy PG. The Evolving Spectrum of Human African Trypanosomiasis. QJM : monthly journal of the Association of Physicians. 2023 Dec 8:():. pii: hcad273. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcad273. Epub 2023 Dec 8 [PubMed PMID: 38065835]

Krafsur ES, Maudlin I. Tsetse fly evolution, genetics and the trypanosomiases - A review. Infection, genetics and evolution : journal of molecular epidemiology and evolutionary genetics in infectious diseases. 2018 Oct:64():185-206. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2018.05.033. Epub 2018 Jun 6 [PubMed PMID: 29885477]

Solano P, Courtin F, Kaba D, Camara, Kagbadouno M, Rayaisse JB, Jamonneau V, Bucheton B, Bart JM, Thevenon S, Lejon V. [Towards elimination of human African trypanosomiasis]. Medecine tropicale et sante internationale. 2023 Mar 31:3(1):. pii: mtsi.v3i1.2023.317. doi: 10.48327/mtsi.v3i1.2023.317. Epub 2023 Feb 10 [PubMed PMID: 37525637]

Van den Bossche P, de La Rocque S, Hendrickx G, Bouyer J. A changing environment and the epidemiology of tsetse-transmitted livestock trypanosomiasis. Trends in parasitology. 2010 May:26(5):236-43. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2010.02.010. Epub 2010 Mar 19 [PubMed PMID: 20304707]

Hasker E, Hope A, Bottieau E. Gambiense human African trypanosomiasis: the bumpy road to elimination. Current opinion in infectious diseases. 2022 Oct 1:35(5):384-389. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000860. Epub 2022 Aug 3 [PubMed PMID: 35942856]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBottieau E, Clerinx J. Human African Trypanosomiasis: Progress and Stagnation. Infectious disease clinics of North America. 2019 Mar:33(1):61-77. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2018.10.003. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30712768]

Hamidou Soumana I, Tchicaya B, Rialle S, Parrinello H, Geiger A. Comparative Genomics of Glossina palpalis gambiensis and G. morsitans morsitans to Reveal Gene Orthologs Involved in Infection by Trypanosoma brucei gambiense. Frontiers in microbiology. 2017:8():540. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00540. Epub 2017 Apr 3 [PubMed PMID: 28421044]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFunk S, Nishiura H, Heesterbeek H, Edmunds WJ, Checchi F. Identifying transmission cycles at the human-animal interface: the role of animal reservoirs in maintaining gambiense human african trypanosomiasis. PLoS computational biology. 2013:9(1):e1002855. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002855. Epub 2013 Jan 17 [PubMed PMID: 23341760]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTorr SJ, Chamisa A, Mangwiro TN, Vale GA. Where, when and why do tsetse contact humans? Answers from studies in a national park of Zimbabwe. PLoS neglected tropical diseases. 2012:6(8):e1791. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001791. Epub 2012 Aug 28 [PubMed PMID: 22953013]

Garcia A, Courtin D, Solano P, Koffi M, Jamonneau V. Human African trypanosomiasis: connecting parasite and host genetics. Trends in parasitology. 2006 Sep:22(9):405-9 [PubMed PMID: 16837245]

World Health Organization. Control and surveillance of human African trypanosomiasis. World Health Organization technical report series. 2013:(984):1-237 [PubMed PMID: 24552089]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePays E, Radwanska M, Magez S. The Pathogenesis of African Trypanosomiasis. Annual review of pathology. 2023 Jan 24:18():19-45. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathmechdis-031621-025153. Epub 2022 Sep 2 [PubMed PMID: 36055769]

Ortiz HIA, Farina JM, Saldarriaga C, Mendoza I, Sosa Liprandi A, Wyss F, Burgos LM, Alexander B, Baranchuk A. Human African trypanosomiasis & heart. Expert review of cardiovascular therapy. 2020 Dec:18(12):859-865. doi: 10.1080/14779072.2020.1828066. Epub 2020 Oct 14 [PubMed PMID: 32967478]

Chimelli L, Scaravilli F. Trypanosomiasis. Brain pathology (Zurich, Switzerland). 1997 Jan:7(1):599-611 [PubMed PMID: 9034568]

Bonnet J, Boudot C, Courtioux B. Overview of the Diagnostic Methods Used in the Field for Human African Trypanosomiasis: What Could Change in the Next Years? BioMed research international. 2015:2015():583262. doi: 10.1155/2015/583262. Epub 2015 Oct 4 [PubMed PMID: 26504815]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceÁlvarez-Rodríguez A, Jin BK, Radwanska M, Magez S. Recent progress in diagnosis and treatment of Human African Trypanosomiasis has made the elimination of this disease a realistic target by 2030. Frontiers in medicine. 2022:9():1037094. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.1037094. Epub 2022 Nov 3 [PubMed PMID: 36405602]

Miller JM, Binnicker MJ, Campbell S, Carroll KC, Chapin KC, Gilligan PH, Gonzalez MD, Jerris RC, Kehl SC, Patel R, Pritt BS, Richter SS, Robinson-Dunn B, Schwartzman JD, Snyder JW, Telford S 3rd, Theel ES, Thomson RB Jr, Weinstein MP, Yao JD. A Guide to Utilization of the Microbiology Laboratory for Diagnosis of Infectious Diseases: 2018 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Society for Microbiology. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2018 Aug 31:67(6):e1-e94. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy381. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29955859]

Lindner AK, Lejon V, Chappuis F, Seixas J, Kazumba L, Barrett MP, Mwamba E, Erphas O, Akl EA, Villanueva G, Bergman H, Simarro P, Kadima Ebeja A, Priotto G, Franco JR. New WHO guidelines for treatment of gambiense human African trypanosomiasis including fexinidazole: substantial changes for clinical practice. The Lancet. Infectious diseases. 2020 Feb:20(2):e38-e46. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30612-7. Epub 2019 Dec 23 [PubMed PMID: 31879061]

. WHO interim guidelines for the treatment of gambiense human African trypanosomiasis. 2019 Aug:(): [PubMed PMID: 31449367]

Neau P, Hänel H, Lameyre V, Strub-Wourgaft N, Kuykens L. Innovative Partnerships for the Elimination of Human African Trypanosomiasis and the Development of Fexinidazole. Tropical medicine and infectious disease. 2020 Jan 27:5(1):. doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed5010017. Epub 2020 Jan 27 [PubMed PMID: 32012658]

Simarro PP, Franco J, Diarra A, Postigo JA, Jannin J. Update on field use of the available drugs for the chemotherapy of human African trypanosomiasis. Parasitology. 2012 Jun:139(7):842-6. doi: 10.1017/S0031182012000169. Epub 2012 Feb 6 [PubMed PMID: 22309684]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePelfrene E, Harvey Allchurch M, Ntamabyaliro N, Nambasa V, Ventura FV, Nagercoil N, Cavaleri M. The European Medicines Agency's scientific opinion on oral fexinidazole for human African trypanosomiasis. PLoS neglected tropical diseases. 2019 Jun:13(6):e0007381. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007381. Epub 2019 Jun 27 [PubMed PMID: 31246956]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMudji J, Blum A, Grize L, Wampfler R, Ruf MT, Cnops L, Nickel B, Burri C, Blum J. Gambiense Human African Trypanosomiasis Sequelae after Treatment: A Follow-Up Study 12 Years after Treatment. Tropical medicine and infectious disease. 2020 Jan 11:5(1):. doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed5010010. Epub 2020 Jan 11 [PubMed PMID: 31940846]