Introduction

The trapezius muscle is a large superficial back muscle that resembles a trapezoid. It extends from the external protuberance of the occipital bone to the lower thoracic vertebrae and laterally to the spine of the scapula. The trapezius has upper, middle, and lower groups of fibers.

The ventral rami of C3 and C4 innervate the sensory functions of the trapezius. The spinal accessory nerve (cranial nerve XI) innervates the motor function of the trapezius.

The function of the trapezius is to stabilize and move the scapula. The upper fibers can elevate and upwardly rotate the scapula and extend the neck. The middle fibers adduct (medially retract) the scapula. The lower fibers depress and aid the upper fibers in upwardly rotating the scapula. These motions allow for the scapula to rotate against the levator scapulae and the rhomboid muscles. This rotation, in conjunction with the deltoid muscle, is essential for throwing objects.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The trapezius is a muscle comprised of particularly long muscle fibers spanning a large width of the upper back. Functionally, this allows the trapezius to assist in mainly postural attributes, allowing and supporting the spinal column to remain erect when the person is standing. The trapezius is one of the broadest and most superficial (closest to the skin) muscles of the upper back and trunk. It is often used as a landmark when dissecting a cadaver because it is encountered first. The trapezius is triangular, broad, and thin; it covers the upper back of the shoulders and neck. Its attachment points consist of the spinous process of C7-T12 of the spine, ligamentum nuchae, scapulae, clavicles, and ribs. While the trapezius muscle is mainly postural, it is also used for active movements such as side bending, rotation of the head, elevating and depressing the shoulders, and internally rotating the arm. The trapezius elevates, depresses, and retracts the scapula. The descending muscle fibers of the trapezius muscle internally rotate the arms. The transverse muscle fibers retract the scapulae, and the ascending muscle fibers medially rotate the scapulae.

Thus, there are three components of the trapezius muscle.[1] The superior portion attaches to the skull (external occipital protuberance and superior nuchal line) and neck (ligamentum nuchae). This portion of the muscle extends the head at the neck. The middle portion attaches to the upper part of the spinous processes of C7-T12. This portion adducts (draws together) the two scapulae. The inferior portion (lower part of C7-T12) depresses the scapula. Muscular insertions are onto the scapular spine, acromion process, and the lateral third of the clavicle. The axio-appendicular muscles attach the body wall to the arm. The real significance of the functions of the muscles that attach the body wall to the scapula is that they fix the scapula so that the scapulohumeral muscles that attach the scapula to the arm can function effectively.[2]

One way to visualize the actions of the back and upper limb muscles is to visualize a large construction crane. The giant arm is the most obvious feature of the crane, but the jacks that anchor the cab of the crane to the ground are essential to its stability. Without these muscles, the upper limb (the arm of the crane) would be useless.

To visualize the actions of the trapezius, consider a soldier coming to attention. The head is extended at the skull and neck (action of the upper portion of the trapezius). The scapulae are adducted, straightening the middle back and arms (action of the middle portion of the trapezius). The lower back and shoulder are extended (action of the inferior portion of the trapezius. The result is the "ramrod straight" posture.

The unequal development of the three portions of the trapezius causes muscle imbalances and posture disturbances.

Injury to the spinal accessory nerve (cranial nerve XI) can result in denervation and subsequent loss of motor function of the trapezius, resulting in muscle wasting (atrophy). Hypotonia and hyporeflexia are also characteristic of this lower motor neuron syndrome. The spinal accessory nerve (cranial nerve XI) and the trapezius can be examined during a clinical examination by asking the patient to shrug their shoulders passively and observe the shoulders for a shoulder droop. If pain occurs with passive stretching, this may be significant. Next, the examiner's hands are placed on the patient's shoulders while exerting downward pressure. The patient is then instructed to shrug the shoulders against this resistance allowing for assessment of any weakness. Unless strength against resistance is assessed, lesser degrees of muscle weakness may go unnoticed.

The trapezius forms the posterior border of the posterior triangle of the neck. The sternocleidomastoid muscle (also innervated by the spinal accessory nerve) forms the anterior boundary. The clavicle completes the triangle.

Embryology

All musculature of the human body, both striated and smooth muscle, with few exceptions, arises from the mesoderm. The few exceptions arise from the ectoderm. The trapezius and sternocleidomastoideus muscle originates initially as a singular mass in the lateral occipital area. At this very early period, it is innervated by the spinal accessory nerve (CN XI in the adult form).

As the muscle mass moves into its adult position, it extends and moves caudally, carrying the nerve with it. This single mass splits into the trapezius and the sternocleidomastoideus at approximately the 20th week of gestation. It is not unusual for the muscle to receive secondary new nerves while retaining its original nerve CN XI and later receiving branches from the cervical plexus.[3]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Two main variants of the vascular supply to the trapezius develop from three common sources.[4] The most common variant involves the main blood supply from the transverse cervical artery, with collateral supply from the dorsal scapular artery for the superior portion and the posterior intercostal arterial branches for the deep portions. A less common variant has more blood supply from the dorsal scapular artery.[4]

Nerves

The trapezius is innervated for motor functions by the spinal accessory nerve (cranial nerve XI). Shoulder range of motion (ROM) with cephalad motion of the shoulders - shrugging - is a common physical exam maneuver to test CN XI.[5] Sensory fibers of the trapezius muscles, including pain and proprioception (the sense of position in space), occur via the ventral rami of the third (C3) and fourth (C4) cervical nerves. Logic may dictate that because the trapezius muscle is on the back, it would be innervated by the dorsal rami; the trapezius muscle is not a back muscle but a muscle of the upper limb and is innervated by the ventral rami.

Spinal Accessory Nerve

The spinal accessory nerve is a cranial nerve arising from the ventral roots of upper cervical spinal nerves to the level of C6. It then passes through the foramen magnum to enter the cranium. It then passes through the jugular foramen, where it accompanies the internal jugular vein and vagus nerve to lie medial to the sternocleidomastoid, which it innervates.[6] The spinal accessory nerve then passes through the posterior triangle of the neck.[7] The three sides of the triangle are formed by the sternocleidomastoid, trapezius, and clavicle. The nerve then passes beneath the trapezius, innervating it.[6][7][8]

Muscles

Additional muscles that either assist or are assisted by the trapezius include the latissimus dorsi (innervated by the dorsal scapular nerve), rhomboid major and minor (innervated by the dorsal scapular nerve), and the levator scapulae (innervated by the dorsal scapular nerve and some of the cervical ventral rami). The trapezius and semispinalis capitis muscles create the main mass of muscle at the occipital region of the base of the skull.

The latissimus dorsi is a powerful extensor of the arm at the shoulder. The rhomboid major and minor serve to adduct the scapula. They also adduct and extend the arm at the shoulder, as well as depressing the scapula, and rotating the arm medially.

The sternocleidomastoid muscle is also innervated by the spinal accessory nerve (cranial nerve XI). As the name implies, the sternocleidomastoid muscle has an origin at the clavicle (cleido) and at the sternum. It inserts on the mastoid process of the temporal bone. Acting together, the two sternocleidomastoid muscles flex the head at the neck, whereas the upper portions of the two trapezius muscles extend the head at the neck.

Physiologic Variants

Anatomical variants of the trapezius muscle, though statistically rare, are noteworthy and diverse. Many of these variants are developmental in nature and related to agenesis of the trapezius, whether unilateral or bilateral, resulting in hypoplasia or accessory lobes of muscle.[9]

One reported case of heritable absence of the trapezius reported that the daughter of two parents with absent trapezius muscles also had the absence of the muscle. Other phenomena would be dysfunction or absence of the spinal accessory nerve (CN XI), causing hypoplasia of the trapezius muscles, not an actual absence.

Surgical Considerations

Surgical considerations are limited due to the sustainability of quality of life if the trapezius is injured. If dissection of the accessory nerve occurs, attempts at repair have been attempted, but success rates are low. This procedure is often forgone because of these poor outcomes. One of the most common surgical interventions involving the trapezius region includes a trapezius flap for patients with congenital or acquired lateral craniofacial or lateral basilar skull defects. Flaps of the trapezius also are used for oral or pharyngeal defects.[10]

Injury to the spinal accessory nerve can occur when exploring the posterior triangle of the neck during lymphadenectomy for cancer staging. Lymph nodes in this anatomical location are part of the deep cervical lymphatic lymph node chain. Sampling these nodes is important in staging many cancers of the head. For example, a cancer of the tongue may require sampling of these nodes to determine the presence or absence of nodal metastases.[11][12]

Clinical Significance

Trapezius hypertonicity and spasm are common causes of tension headaches among the general population. The path of the accessory nerve and occipital nerve predispose to entrapment, causing the classic "ram's horn" distribution of a tension headache. Tension headaches are bilateral, throbbing, traveling from the occipital region and wrapping around to the top of the head and forehead region. Stress, posture, and inadequate pre-activity stretching can exacerbate these symptoms. Tension headaches are not characterized by prodromal or sensorineural exacerbations related to light or sound, which would be found in cases of migraine headaches. Tension headaches are often treated with a suboccipital release, stretching, stress/anxiety relief, and NSAIDs.[13]

Spinal Accessory Nerve Lesions

The spinal accessory nerve can be damaged intracranially or just below the jugular foramen by tumors or trauma, including surgical trauma. Lesions in either location will cause paralysis, hypotonia, hyporeflexia, and atrophy of the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles and are classified as lower motor neuron lesions.[14] Only the trapezius will be denervated if the nerve is injured within the posterior triangle.[15][16][17]

Other Issues

Myofascial trigger points can be dry-needled in treating pain. This is especially useful in treating athletes who have to function with their arms raised above the head. It is also useful in treating shoulder impingement syndrome.[18]

Unilateral neck pain in violinists is associated with decreased strength in the trapezius.[19]

Onabotulinumtoxin A can be used to decrease the muscle mass of the trapezius bilaterally in women who want a more aesthetically pleasing shoulder line.[20]

Media

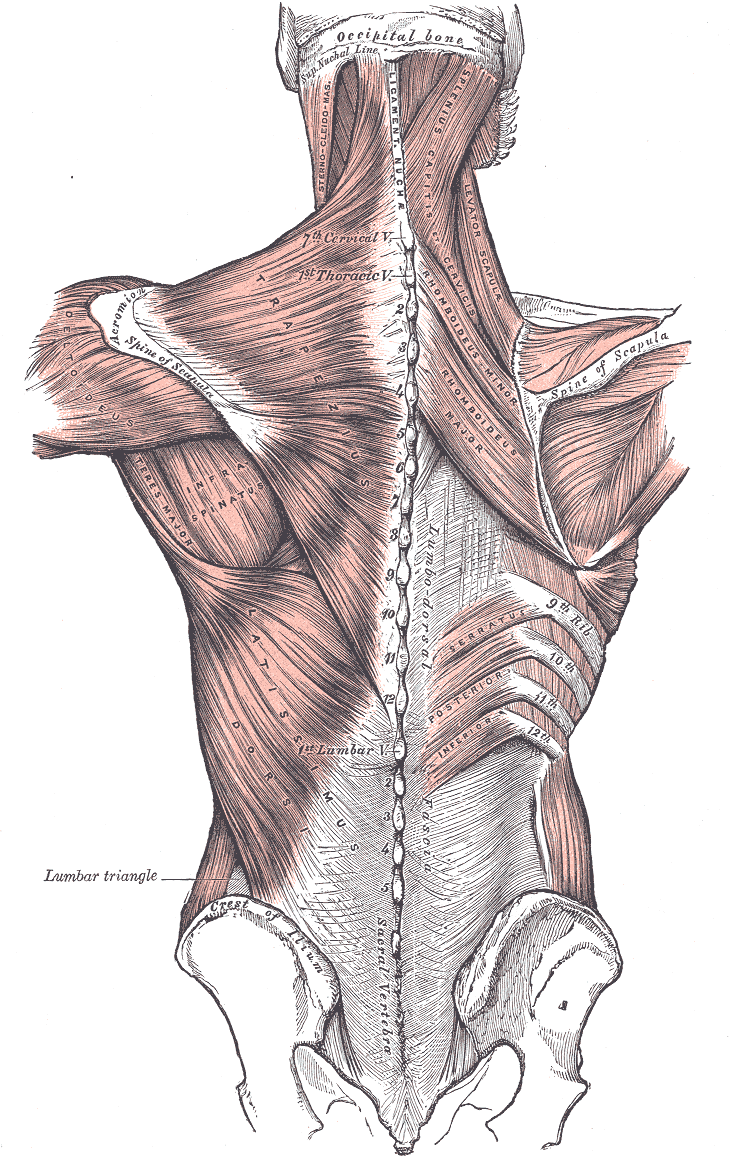

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Posterior Axioappendicular Muscles. This image depicts the posterior axioappendicular muscles, including the trapezius, levator scapulae, latissimus dorsi, rhomboid major and minor, and serratus posterior inferior. Additional muscles shown in the image include the sternocleidomastoid, splenius capitis of services, deltoideus, teres major, and infraspinatus. Bony structures featured in the image include the vertebral column, occipital bone and superior nuchal line, scapular spine, iliac crest, and sacral vertebra. Furthermore, the ligamentum nuchae and lumbar triangle are also depicted in this image.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

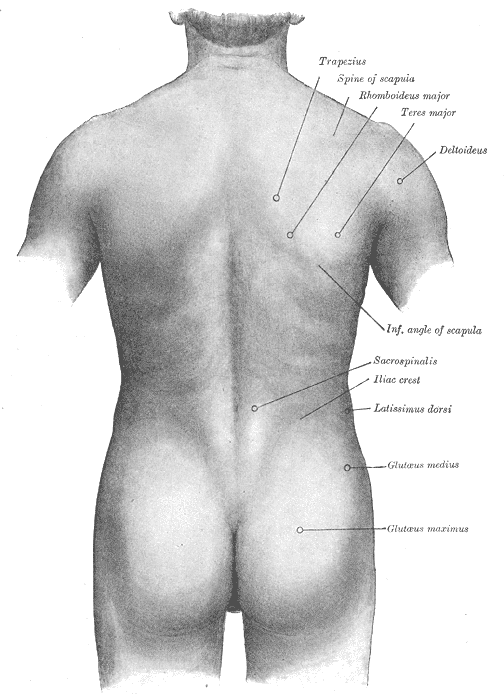

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Surface Anatomy of the Back. This illustration shows the trapezius, spine of the scapula, rhomboideus major, teres major, deltoideus, inferior angle of the scapula, sacrospinalis, iliac crest, latissimus dorsi, and glutaeus medius and maximus.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

References

Henderson ZJ, Bohunicky S, Rochon J, Dacanay M, Scribbans TD. Muscle Activation in Specific Regions of the Trapezius During Modified Kendall Manual Muscle Tests. Journal of athletic training. 2021 Oct 1:56(10):1078-1085. doi: 10.4085/545-20. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33626133]

Camargo PR, Neumann DA. Kinesiologic considerations for targeting activation of scapulothoracic muscles - part 2: trapezius. Brazilian journal of physical therapy. 2019 Nov-Dec:23(6):467-475. doi: 10.1016/j.bjpt.2019.01.011. Epub 2019 Feb 3 [PubMed PMID: 30797676]

Badura M, Grzonkowska M, Baumgart M, Szpinda M. Quantitative Anatomy of the Trapezius Muscle in the Human Fetus. Advances in clinical and experimental medicine : official organ Wroclaw Medical University. 2016 Jul-Aug:25(4):605-9. doi: 10.17219/acem/61899. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27629832]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNetterville JL, Wood DE. The lower trapezius flap. Vascular anatomy and surgical technique. Archives of otolaryngology--head & neck surgery. 1991 Jan:117(1):73-6 [PubMed PMID: 1986765]

Bae JH, Lee JS, Choi DY, Suhk J, Kim ST. Accessory nerve distribution for aesthetic botulinum toxin injections into the upper trapezius muscle: anatomical study and clinical trial : Reproducible BoNT injection sites for upper trapezius. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2018 Nov:40(11):1253-1259. doi: 10.1007/s00276-018-2059-4. Epub 2018 Jun 26 [PubMed PMID: 29946827]

AlShareef S, Newton BW. Accessory Nerve Injury. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30335278]

Ellis S, Brassett C, Glibbery N, Cheema J, Madenlidou S. The spinal accessory nerve and its entry point into the posterior triangle of the neck. Folia morphologica. 2023:82(2):256-260. doi: 10.5603/FM.a2022.0014. Epub 2022 Feb 21 [PubMed PMID: 35187635]

Périé S, Lesnik M, Samaha S, Lacau St Guily J. How to release neck dissections: Role of the triangle between the spinal accessory nerve and the internal jugular vein. European annals of otorhinolaryngology, head and neck diseases. 2017 May:134(3):201-203. doi: 10.1016/j.anorl.2016.10.002. Epub 2016 Nov 10 [PubMed PMID: 27840043]

Ranade AV, Rai R, Rai AR, Dass PM, Pai MM, Vadgaonkar R. Variants of latissimus dorsi with a perspective on tendon transfer surgery: an anatomic study. Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery. 2018 Jan:27(1):167-171. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2017.06.046. Epub 2017 Sep 19 [PubMed PMID: 28939333]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFrobert P, Bekara F, Bertheuil N, Delay E, Herlin C, Chaput B. The trapezius perforator flap: Versatility for locoregional reconstruction. Annales de chirurgie plastique et esthetique. 2019 Feb:64(1):61-67. doi: 10.1016/j.anplas.2018.06.001. Epub 2018 Jun 22 [PubMed PMID: 29937362]

Sahin AA, Gilligan TD, Caudell JJ. Challenges With the 8th Edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual for Breast, Testicular, and Head and Neck Cancers. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network : JNCCN. 2019 May 1:17(5.5):560-564. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2019.5015. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31117030]

Duprez F, Berwouts D, De Neve W, Bonte K, Boterberg T, Deron P, Huvenne W, Rottey S, Mareel M. Distant metastases in head and neck cancer. Head & neck. 2017 Sep:39(9):1733-1743. doi: 10.1002/hed.24687. Epub 2017 Jun 26 [PubMed PMID: 28650113]

Rodríguez-Huguet M, Gil-Salú JL, Rodríguez-Huguet P, Cabrera-Afonso JR, Lomas-Vega R. Effects of Myofascial Release on Pressure Pain Thresholds in Patients With Neck Pain: A Single-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial. American journal of physical medicine & rehabilitation. 2018 Jan:97(1):16-22. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000000790. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28678033]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMassey EW. Spinal accessory nerve lesions. Seminars in neurology. 2009 Feb:29(1):82-4. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1124026. Epub 2009 Feb 12 [PubMed PMID: 19214936]

Amirlak B, Lu KB, Erickson CR, Sanniec K, Totonchi A, Peled ZM, Cheng JC. In-Depth Look at the Anatomical Relationship of the Lesser Occipital Nerve, Great Auricular Nerve, and Spinal Accessory Nerve and Their Implication in Safety of Operations in the Posterior Triangle of the Neck. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2020 Sep:146(3):509-514. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000007049. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32453270]

Sharp E, Roberts M, Żurada-Zielińska A, Zurada A, Gielecki J, Tubbs RS, Loukas M. The most commonly injured nerves at surgery: A comprehensive review. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2021 Mar:34(2):244-262. doi: 10.1002/ca.23696. Epub 2020 Nov 12 [PubMed PMID: 33090551]

Popovski V, Benedetti A, Popovic-Monevska D, Grcev A, Stamatoski A, Zhivadinovik J. Spinal accessory nerve preservation in modified neck dissections: surgical and functional outcomes. Acta otorhinolaryngologica Italica : organo ufficiale della Societa italiana di otorinolaringologia e chirurgia cervico-facciale. 2017 Oct:37(5):368-374. doi: 10.14639/0392-100X-844. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29165431]

Kamali F, Sinaei E, Morovati M. Comparison of Upper Trapezius and Infraspinatus Myofascial Trigger Point Therapy by Dry Needling in Overhead Athletes With Unilateral Shoulder Impingement Syndrome. Journal of sport rehabilitation. 2019 Mar 1:28(3):243-249. doi: 10.1123/jsr.2017-0207. Epub 2018 Nov 30 [PubMed PMID: 29364040]

Park KN, Jung DY, Kim SH. Trapezius and serratus anterior muscle strength in violinists with unilateral neck pain. Journal of back and musculoskeletal rehabilitation. 2020:33(4):631-636. doi: 10.3233/BMR-181147. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31594199]

Benítez PA. Onabotulinumtoxin A for correcting trapezius muscle hypertrophy in Asian women. Journal of cosmetic dermatology. 2022 Jun:21(6):2677-2679. doi: 10.1111/jocd.14423. Epub 2021 Oct 7 [PubMed PMID: 34622530]