Introduction

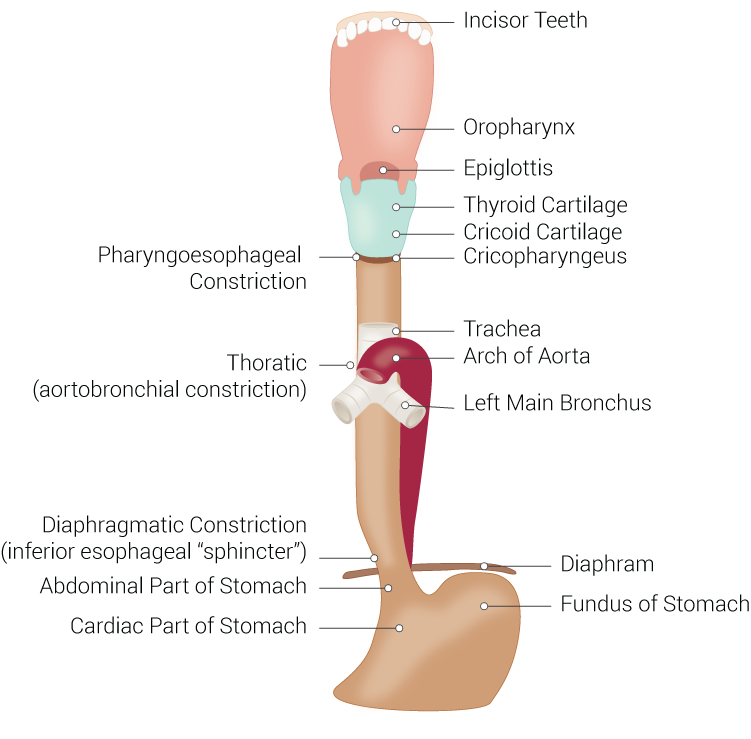

The upper digestive tract is the primary site of tissue damage due to caustic ingestion. This part of the gut runs from the head, neck, mediastinum, and epigastric area. The oral region, pharynx, esophagus, stomach, and duodenum comprise the upper gastrointestinal tract (see Image. Digestive and Respiratory Anatomical Structures Connected to the Esophagus).

The oral region (mouth) is the entryway to the digestive system, composed of the oral cavity, gingivae, teeth, tongue, palate, and palatine tonsil area. Mechanical and some enzymatic food digestion take place in the oral cavity. Nonkeratinized stratified squamous epithelium lines most oral mucosal surfaces. Masticatory areas like the gingivae and hard palate have keratinized or parakeratinized stratified squamous epithelium.[69] Mastication muscles surround the oral region.

The pharynx passes from the cranial base to the C6 vertebra level. This upper gut area is divided into the nasopharynx, oropharynx, and laryngopharynx. The nasopharynx and oropharynx have sensory functions during eating. The oropharynx and laryngopharynx help in the transit of food boluses from the oral cavity to the esophagus.

Head and neck structures surrounding the pharynx include the upper respiratory tract, salivary glands, thyroid and parathyroid glands, vagus nerve and its branches, cervical nerves, carotid arteries and its branches, external and internal jugular veins, deglutition muscles, and lymph nodes. Nonkeratinized stratified squamous epithelium lines the pharyngeal mucosal surfaces.

The esophagus is a long muscular tube where food passes from the mouth and pharynx to the stomach. This part of the gut has cervical, thoracic, and abdominal regions. In the neck, the esophagus lies posterior to the larynx and trachea. The thoracic esophagus runs in the mediastinum anterior to the vertebral column, posterior to the trachea, and to the right of the aorta. The abdominal esophagus begins at the T11 vertebral level, where the muscular tube opens to the stomach.

The following are the 3 esophageal constrictions:

- Cervical constriction: located 15 cm from the incisors and formed by the cricopharyngeus muscle; also known as the upper esophageal sphincter (UES)

- Broncho-aortic constriction: a compound constriction; the aortic arch crosses the esophagus 22.5 cm from the incisors, while the left main bronchus crosses the tube 27.5 cm from the incisors

- Diaphragmatic constriction: located 40 cm from the incisors; the area passing through the esophageal hiatus of the diaphragm, also known as the lower esophageal sphincter (LES)

These constrictions are important landmarks during esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and radiologic evaluation of esophageal lesions.

The esophageal mucosa is lined by nonkeratinized stratified squamous epithelium. The upper third of the esophagus has striated muscles. The lower third has smooth muscles. The middle third has mixed striated and smooth muscles. The esophagus has no serosa, so infections and tumors can quickly spread from this muscular tube to the neighboring regions.

The structures surrounding the esophagus include the following:

- In the neck: trachea, aortic and carotid artery branches, vagal and cervical nerve branches, thyroid and parathyroid glands, and thoracic duct

- In the trunk: thoracic duct, trachea, main bronchi, heart, the great blood vessels, pericardium, vagus nerve and branches, esophageal plexus, and azygos vein

- In the abdomen: posterior aspect of the liver, vagus nerve, esophageal plexus, diaphragm, abdominal aorta and branches, stomach fundus

The stomach starts at the esophagogastric junction (EGJ), where the mucosal lining transitions from squamous to simple columnar epithelium. Gastric secretions, characterized by high acidity, serve dual roles as digestive agents and potent defense mechanisms against pathogens due to their antimicrobial properties. The mucus protects the stomach from its secretions.

The duodenum is the proximal part of the small intestine, neutralizing acidic chyme and accomplishing most of the digestive process. Bicarbonate secretions raise the duodenal pH. This part of the upper gastrointestinal tract has microvilli and simple columnar epithelium, as it is specialized for food digestion and absorption.

Caustic ingestions can injure any part of the upper digestive tract. The esophagus is most vulnerable to alkaline damage, while the stomach is most prone to acidic injury. Severe cases can cause overspills or gut perforation that can spread the damage to neighboring structures.

Caustic ingestions are severe causes of morbidity and mortality and can affect all age groups. About 80% of caustic ingestion cases in the United States occur in children. For the best outcomes, critical ingestions require coordination between surgical and medical teams.[1]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Caustic exposure can be accidental or intentional. Accidental exposures are most common in young children, often termed "exploratory ingestions." Accidental caustic ingestion often occurs in small amounts and typically involves household cleaners with low concentrations of chemicals like bleach and ammonia. Meanwhile, intentional exposures often result from self-harm attempts and involve large amounts of highly concentrated caustic chemicals.

Most caustic exposures involve oral ingestion (76%) and occur at home (93%). More than 80% of cases are unintentional. Substances ingested are either highly acidic or highly alkaline, requiring different treatment approaches.[1][2]

Epidemiology

The American Association of Poison Control Centers reported that 180,000 caustic exposure incidents were documented in the United States in 2019. Most cases involved pediatric accidental ingestion of household cleaning products. The rest were comprised of intentional caustic ingestion cases among adults. The alkaline substance lye is the most frequently reported component in caustic ingestions.

Pathophysiology

Generally, the pathophysiology underscoring tissue damage depends on the ingested agent's pH. Substances with pH over 7.0 are alkaline, and below 7.0 are acidic. Extremes of pH—specifically below 3.0 and above 11.0—are of greatest concern in human exposures. Strong alkalis and acids can damage tissues by different mechanisms.

Alkalis are classically associated with liquefactive necrosis. The process involves saponification and subsequent disruption of the lipid-rich cell membranes. Cell lysis releases digestive enzymes, dissolving the surrounding tissues. Strong alkalis can penetrate tissues more deeply than acids and cause more extensive tissue damage.[3]

In contrast, acids are classically associated with coagulative necrosis. Acid-related tissue injury is more superficial due to eschar formation, which limits acid penetration into the underlying tissues.[4] Acid ingestions are associated with "skip lesions," where the esophagus sustains discontinuous areas of damage.

However, distinguishing liquefactive from coagulative necrosis is less important in clinical practice. Strong alkalis and acids are equally capable of severe, full-thickness injury to the gastrointestinal tract.[5]

The titrable acid or alkali reserve (TAR) predicts tissue damage potential more accurately than pH. TAR is estimated by the amount of acid or alkali required to bring a substance's pH to 8.00. The higher the TAR, the more corrosive the agent. Still, pH is more often used in practice than TAR, as pH is more readily available and can approximate TAR in many cases. However, substances like zinc chloride and phenol require TAR values for predicting the potential for tissue damage, as these chemicals have near-physiologic pH but very high TAR.[6]

Other factors that will influence the extent and severity of damage include the physical state of the caustic substance (solid, liquid, or gel), tissue contact time, and quantity and concentration of the offending agent.[7]

Histopathology

Initial contact with a caustic substance produces eosinophilic necrosis and hemorrhagic congestion. A fibrinous layer forms over ulcerated areas in the first few days post-injury. Around the 5th day, an esophageal mold, comprised of dead cells, secretions, and food remnants, forms over the lesion.

Tissue repair commences around the 10th day, although edema and lymphatic ectasia can persist for weeks. Fibrosis, scarring, and stenosis can arise in the gastrointestinal mucosa and submucosa. Depending on the injury depth, the muscular layer may become sclerotic, and the esophageal plexus may be permanently damaged. Vascular injury can delay epithelial healing or produce recurrent ulcers.[3]

History and Physical

Individuals with caustic injuries may present unresponsive, breathless, and pulseless. After a quick primary survey, resuscitation must be administered promptly for patients with signs of cardiorespiratory arrest, regardless of the cause. Airway, breathing, and circulation must be stabilized. Patients should be monitored continuously on telemetry, with frequent assessments of vital signs. Once stabilized, the secondary survey may be initiated.

When taking the history of individuals with suspected caustic ingestion, 5 signficant details (the "5 Ws") must be elicited:

- Who - patient's personal information, including age and weight; details about accompanying family, friends, or witnesses are also important

- What - characteristics of the substances ingested

- When - time and date of ingestion

- Where - route of poisoning and geographic location of the incident

- Why - determines if the caustic ingestion is intentional

Environmental factors may contribute to the pathology. Thus, the geographic location should be noted. Meanwhile, intentionality must be established, as the final disposition, eg, whether psychiatric referral is required, depends on this information. If caustic ingestion is nonaccidental, overdosing with other substances, such as acetaminophen, salicylates, cocaine, alcohol, and opioids, must also be considered.

Patients with caustic ingestion may be asymptomatic in one extreme or develop severe manifestations in another. Vomiting, drooling, chest pain, abdominal pain, and breathing and swallowing difficulty may be reported. Hematemesis may be caused by blood vessel erosion.

Physical examination may reveal oral and tongue edema and drooling. Upper airway edema may lead to vocal changes, stridor, and respiratory distress. Esophageal perforation can cause mediastinitis and peritonitis. Mediastinitis typically presents with nonspecific signs like tachycardia and fever. Occasionally, it may produce the Hamman sign—a systolic precordial crunching sound heard on auscultation. Peritonitis presents with abdominal tenderness and rigidity.[8] A complete exam should be performed to assess for other injuries, particularly oral and orbital burns.

Evaluation

Initial lab studies may include a complete blood count (CBC), coagulation studies, complete metabolic profile (CMP), and arterial or venous blood gas. The CBC may show inflammation-associated neutrophilia. Dehydration may falsely elevate the hemoglobin and hematocrit. Hematemesis may reduce hemoglobin to abnormal levels if severe.

The CMP can help detect electrolyte imbalances in patients with repeated vomiting. This test can also provide baseline renal and liver function information, which is crucial if surgery is contemplated. Blood gases help examine the severity of respiratory damage.

A comprehensive drug panel may be contemplated if multiple drug ingestion is also suspected.

Plain chest and abdominal radiography may identify free air in the mediastinum (pneumomediastinum) or peritoneum (pneumoperitoneum). Caustic substance aspiration may produce infiltrates on chest x-ray. An upper gastrointestinal series with a water-soluble contrast medium may confirm esophageal perforation but is not required if EGD is available (see Image. Esophageal Radiography With Contrast).

EGD is currently the gold standard in evaluating injuries from caustic ingestion (see Image. Esophagus Examination on Esophagogastroduodenoscopy).[9] The prognosis and stricture formation risk may be predicted based on the injury grade found on EGD (see under Staging below). However, a major decision point involves which patients should get an EGD. Some expert groups suggest that all patients with caustic exposure, regardless of severity, should receive an EGD, as asymptomatic patients can still have significant injury.[10][11] However, others report that accidental or unintentional ingestion has a low risk of clinically significant esophageal damage.[12][13]

EGD should be strongly considered in symptomatic patients, especially if they have posterior pharyngeal burns, stridor, respiratory distress, chest or abdominal pain, or inability to tolerate oral liquids.[14][15] The procedure must also be recommended for any patient who intentionally ingests a caustic substance, regardless of their symptomatology.[16] However, in asymptomatic patients without oral or mucosal burns, EGD may be deferred on physical examination.

Early endoscopy shows favorable results. However, a personalized approach is recommended for caustic ingestions, as some individuals may have a greater need for immediate surgical intervention and hemodynamic stabilization.[17] The most common injury found on early endoscopy is a grade I injury. Early endoscopy helps guide treatment if evidence of severe manifestations like mediastinitis is lacking.[18][19] The general consensus is to obtain EGD within 24 hours. Literature suggests that EGD may be safe up to 96 hours post-ingestion if performed with gentle insufflation.[20]If the procedure is delayed longer, iatrogenic perforation from damaging friable tissue may occur.

Alternative or adjunctive modalities for evaluating caustic ingestion-related injuries include endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT).[21] EUS remains under investigation for use in the treatment of caustic injuries. One study showed that, as an adjunct test, EUS does not increase the accuracy of EGD in predicting complications from caustic ingestion.[22] However, other studies suggest that EUS may be useful in determining prognosis, specifically stricture formation when used with an appropriate grading system. Overall, the evidence is insufficient to recommend EUS as part of the standard caustic ingestion evaluation protocol.

Meanwhile, CECT has gained significant attention as a potential alternative to EGD. This modality is non-invasive, fast, and able to assess deep structures. The study of choice is a CECT of the neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis.

Several studies compared the ability of CECT with EGD to grade tissue damage, guide surgical intervention, and predict the risk of stricture formation.[23][24][25] CECT has been shown to have high specificity but low sensitivity in predicting stricture formation. Additionally, CECT findings may not correlate well with endoscopic grading.[26][27] Evidence is insufficient to support CECT as a replacement for EGD in evaluating upper gastrointestinal injury. However, this modality remains a useful EGD adjunct when managing caustic ingestion.

Treatment / Management

The airway should be secured in patients with signs of impending respiratory failure, including drooling, hypoxia, and vocal changes. One study showed that 50% of adults with caustic ingestions required intubation. Multi-site large-bore intravenous access should be promptly obtained and intravenous fluids administered for patients who display signs of shock. Vasopressors should be initiated for patients who remain hypotensive despite adequate fluid challenge.

Early interventions that have been described for caustic ingestion include pH neutralization and dilution with water or milk. The pH may be neutralized by giving a weak acid or base. Animal studies suggest that, if performed correctly, pH neutralization can decrease esophageal injury.[28] However, this practice is limited by titration challenges and the potential for exothermic injury. Additionally, no human data supports the benefit of pH neutralization in managing caustic ingestion. Thus, it is not a recommended treatment for this condition.(B3)

Dilution with milk or water was once proposed to help reduce alkali injury.[29] However, this intervention may only be beneficial within the first few minutes. Little clinical data supports the effectiveness of dilution with milk or water in caustic ingestion, and the treatment may even cause distention-related injury. Dilution with milk or water is currently not recommended in clinical practice.(B3)

Activated charcoal administration should be considered if the caustic agent is zinc or mercuric chloride. Heavy metals can damage mucosal surfaces and be absorbed systemically, causing severe multi-organ toxicity. Activated charcoal can absorb metals in the gut, prevent their enterohepatic recirculation, and hasten their clearance.[30][31][32](B3)

The role of H2-blockers and proton pump inhibitors is yet to be defined. One study suggests that omeprazole may improve EGD grading after 72 hours.[33] Emesis induction should not be used in managing caustic ingestion.(B2)

Nasogastric (NG) tube insertion is controversial. Multiple studies suggest that early NG tube placement may help maintain esophageal patency and reduce stricture formation.[34][35][36] Despite this evidence, blind NG tube placement in the emergency department risks bacterial infection and esophageal perforation.[35] Therefore, NG tube placement should only be considered if performed with direct endoscopic visualization.[37](B2)

Besides acute injury management, the long-term sequelae of caustic ingestion must also be addressed. The most concerning complication is stricture formation. Corticosteroid treatment can theoretically attenuate inflammation and reduce granulation and fibrous tissue formation.[38] Several studies suggest that steroids do not prevent esophageal stenosis, regardless of the injury grade.[39][40][41] However, high-dose methylprednisolone may prevent stenosis in patients with grade 2b injury.[42][43](A1)

Procedural interventions in the treatment of strictures include bougienage,[44] esophageal stent placement,[45][46][47] and endoscopic dilatation. Other potential interventions include administration of vitamin E,[48] ketotifen,[49] phosphatidylcholine,[50] halofunginone,[51] 5-fluorouracil,[52] octreotide, and interferon-α2b.[53] These modalities are still under investigation, and their use is currently not recommended in clinical practice.(B2)

Individuals with suspected mediastinitis, peritonitis, or hemodynamic instability require emergent surgical consultation. Patients with large ingestions and are in shock, acidotic, or coagulopathic may have more severe findings on surgical exploration.[54] Surgical consultation may also be required for patients with high-grade injuries on EGD, CECT, or both.

The goal of emergency surgery is to remove all necrotic tissue. Exploratory laparotomy is the standard approach. The size of the resected area depends on the extent of damage. Small fragments may be removed in some cases. A pancreaticoduodenectomy may be necessary if pancreatic and duodenal injuries are extensive.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of caustic ingestion includes the following:

- Trauma

- Congenital abnormalities

- Direct burns

- Multiple drug ingestion

A complete evaluation can help distinguish between these conditions.

Staging

EGD findings are graded based on the Zargar classification:

- Grade 0 - The esophagus is normal.

- Grade 1 - Mucosal edema and hyperemia are present.

- Grade 2a - Friability, hemorrhages, erosions, blisters, whitish membranes, exudates, and superficial ulcerations may be found.

- Grade 2b - Deep or circumferential ulceration besides 2a lesions may be present.

- Grade 3a - Small and scattered areas of necrosis are seen.

- Grade 3b - Extensive necrosis is present.

For CECT, the following is the grading scale proposed by Bruzzi et al:[24]

- Grade I - The esophageal wall is clearly delineated. Homogenous postcontrast enhancement is appreciated but not edema or fat stranding.

- Grade IIa - Internal esophageal mucosal enhancement is seen. Significant esophageal wall edema appears hypodense. The “target” aspect may be seen. Mediastinal fat stranding is present.

- Grade IIb - A fine rim of esophageal enhancement is present, but the mucosa does not enhance. The esophageal lumen is dilated. Mediastinal fat stranding is seen.

- Grade III - Transmural necrosis is present, as shown by the absence of postcontrast wall enhancement.

Meanwhile, Ryu et al proposed the following CECT-based grading system:[55]

- Grade I - The esophagus wall has no definitive swelling (less than 3 mm, within normal limits).

- Grade II - Edematous wall thickening (greater than 3 mm) is seen without peri-esophageal soft tissue infiltration.

- Grade III - Edematous wall thickening is accompanied by peri-esophageal soft tissue infiltration. A well-demarcated tissue interface is also visible.

- Grade IV - Edematous wall thickening is accompanied by peri-esophageal soft tissue infiltration. Tissue interface blurring or localized fluid collection around the esophagus or descending aorta may also be seen.

Currently, no studies have compared these CECT grading systems. Thus, we have no information on which system is superior.

Prognosis

The prognosis of caustic ingestion depends mostly on the initial injury's extent. Mild-to-moderate ingestions have the most favorable prognosis, while severe ingestions requiring emergency surgery have the worst outcomes. Grade 3 injuries necessitate emergency surgery and significant follow-up care. Mediastinitis is often associated with high-grade injury and also has a poor prognosis.[56][57]

Patients and their families must be primed about the likelihood of complications after surgery. Individuals who survive high-grade caustic injuries experience a significant decline in quality-of-life scores. Surgical teams must consider possible posttreatment outcomes when making the operative plan.[58]

Complications

The most common early sequelae of caustic ingestion are mediastinitis and bleeding-related hemodynamic instability. These complications require emergency surgery. Meanwhile, gastrointestinal stricture is the most common late sequela of caustic ingestion, with the esophagus being the most frequently involved region. Esophageal dilatation is often enough to relieve this condition. However, surgical resection with bypass or replacement may be performed if esophageal dilatation fails or is infeasible. Bowel or gastric tissue may be used in surgical bypass, depending on the stricture's severity.

Stenosis prevention is a controversial topic. Early oral feedings are thought to prevent stricture in patients with a superficial injury. Stent placement has limited success (less than 50%) and high migration rates (up to 25%). No pharmacologic agents have been effective in preventing gastrointestinal stenosis after caustic ingestion.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Surgical care for esophagectomy and severe caustic ingestion-related injuries requires intensive care, as patients may need airway management, hemodynamic support, and parenteral nutrition. Patients' altered eating habits and wound healing needs will require the services of nutritionists. Mental health practitioners must monitor patients' mental status in cases of intentional ingestion.[59][60]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Caustic ingestion prevention requires a community-wide effort due to the heavy social burden it can create. Robust legislation is recommended to regulate packaging practices and ensure children cannot easily access caustic chemicals. Parents must be reminded to keep harmful substances away from children's reach and use properly labeled containers for storing chemicals.

Since most adult ingestions are intentional, access to mental health services must be ensured. Social support systems must be instituted widely to reduce the risk of suicide attempts.[61]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Patients with caustic ingestions are best managed with an interprofessional team approach. Besides emergency clinicians and surgeons, the multidisciplinary team may also include intensivists, nurses, nutrition services, and mental health practitioners. These team members are critical in ensuring that a patient gets the appropriate care in the acute setting and on follow-up. Smooth coordination between these health professionals has been shown to improve outcomes in patients with this condition.[62][63][64][65]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Digestive and Respiratory Anatomical Structures Connected to the Esophagus. Structures include the esophagus, incisor teeth, oropharynx, epiglottis, thyroid cartilage, cricoid cartilage, cricopharyngeus, trachea, arch of aorta, left main bronchus, diaphragm, fundus of stomach, cardiac part of stomach, abdominal part of stomach, diaphragmatic constriction, inferior esophageal sphincter, thoracic, aortobronchial constriction, and pharyngoesophageal constriction.

Illustration by B Palmer

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Hall AH, Jacquemin D, Henny D, Mathieu L, Josset P, Meyer B. Corrosive substances ingestion: a review. Critical reviews in toxicology. 2019 Sep:49(8):637-669. doi: 10.1080/10408444.2019.1707773. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32009535]

Li Y, Langworthy J, Xu L, Cai H, Yang Y, Lu Y, Wallach SL, Friedenberg FK. Nationwide estimate of emergency department visits in the United States related to caustic ingestion. Diseases of the esophagus : official journal of the International Society for Diseases of the Esophagus. 2020 Jun 15:33(6):. pii: doaa012. doi: 10.1093/dote/doaa012. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32129451]

Mamede RC, de Mello Filho FV. Ingestion of caustic substances and its complications. Sao Paulo medical journal = Revista paulista de medicina. 2001 Jan 4:119(1):10-5 [PubMed PMID: 11175619]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKalayarasan R, Ananthakrishnan N, Kate V. Corrosive Ingestion. Indian journal of critical care medicine : peer-reviewed, official publication of Indian Society of Critical Care Medicine. 2019 Dec:23(Suppl 4):S282-S286. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10071-23305. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32021005]

Poley JW, Steyerberg EW, Kuipers EJ, Dees J, Hartmans R, Tilanus HW, Siersema PD. Ingestion of acid and alkaline agents: outcome and prognostic value of early upper endoscopy. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2004 Sep:60(3):372-7 [PubMed PMID: 15332026]

Hoffman RS, Howland MA, Kamerow HN, Goldfrank LR. Comparison of titratable acid/alkaline reserve and pH in potentially caustic household products. Journal of toxicology. Clinical toxicology. 1989:27(4-5):241-6 [PubMed PMID: 2600988]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChen RJ, O'Malley RN, Salzman M. Updates on the Evaluation and Management of Caustic Exposures. Emergency medicine clinics of North America. 2022 May:40(2):343-364. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2022.01.013. Epub 2022 Apr 5 [PubMed PMID: 35461627]

Hoffman RS, Burns MM, Gosselin S. Ingestion of Caustic Substances. The New England journal of medicine. 2020 Apr 30:382(18):1739-1748. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1810769. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32348645]

Contini S, Scarpignato C. Caustic injury of the upper gastrointestinal tract: a comprehensive review. World journal of gastroenterology. 2013 Jul 7:19(25):3918-30. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i25.3918. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23840136]

Katzka DA. Caustic Injury to the Esophagus. Current treatment options in gastroenterology. 2001 Feb:4(1):59-66 [PubMed PMID: 11177682]

Previtera C, Giusti F, Guglielmi M. Predictive value of visible lesions (cheeks, lips, oropharynx) in suspected caustic ingestion: may endoscopy reasonably be omitted in completely negative pediatric patients? Pediatric emergency care. 1990 Sep:6(3):176-8 [PubMed PMID: 2216918]

Gupta SK, Croffie JM, Fitzgerald JF. Is esophagogastroduodenoscopy necessary in all caustic ingestions? Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 2001 Jan:32(1):50-3 [PubMed PMID: 11176325]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceCelik B, Nadir A, Sahin E, Kaptanoglu M. Is esophagoscopy necessary for corrosive ingestion in adults? Diseases of the esophagus : official journal of the International Society for Diseases of the Esophagus. 2009:22(8):638-41. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2009.00987.x. Epub 2009 Jun 9 [PubMed PMID: 19515187]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBosnali O, Moralioglu S, Celayir A, Pektas OZ. Is rigid endoscopy necessary with childhood corrosive ingestion? a retrospective comparative analysis of 458 cases. Diseases of the esophagus : official journal of the International Society for Diseases of the Esophagus. 2017 Feb 1:30(3):1-7. doi: 10.1111/dote.12458. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26822961]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMillar AJ, Cox SG. Caustic injury of the oesophagus. Pediatric surgery international. 2015 Feb:31(2):111-21. doi: 10.1007/s00383-014-3642-3. Epub 2014 Nov 29 [PubMed PMID: 25432099]

Methasate A, Lohsiriwat V. Role of endoscopy in caustic injury of the esophagus. World journal of gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2018 Oct 16:10(10):274-282. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v10.i10.274. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30364838]

Gschossmann JM, Schroeder R, Wyler F, Scheurer U, Schiemann U. [Whether or not to perform an early endoscopy following ingestion of potentially caustic agents - a retrospective longterm analysis in a tertiary referral institution]. Zeitschrift fur Gastroenterologie. 2016 Jun:54(6):548-55. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-106730. Epub 2016 Jun 10 [PubMed PMID: 27284929]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDi Nardo G, Betalli P, Illiceto MT, Giulia G, Martemucci L, Caruso F, Lisi G, Romano G, Villa MP, Ziparo C, Pensabene L, Vassallo F, Quitadamo P. Caustic Ingestion in Children: 1 Year Experience in 3 Italian Referral Centers. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 2020 Jul:71(1):19-22. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000002685. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32142003]

Acehan S, Satar S, Gulen M, Avci A. Evaluation of corrosive poisoning in adult patients. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2021 Jan:39():65-70. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.01.016. Epub 2020 Jan 8 [PubMed PMID: 31982223]

Temiz A, Oguzkurt P, Ezer SS, Ince E, Hicsonmez A. Predictability of outcome of caustic ingestion by esophagogastroduodenoscopy in children. World journal of gastroenterology. 2012 Mar 14:18(10):1098-103. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i10.1098. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22416185]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKamijo Y, Kondo I, Kokuto M, Kataoka Y, Soma K. Miniprobe ultrasonography for determining prognosis in corrosive esophagitis. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2004 May:99(5):851-4 [PubMed PMID: 15128349]

Chiu HM, Lin JT, Huang SP, Chen CH, Yang CS, Wang HP. Prediction of bleeding and stricture formation after corrosive ingestion by EUS concurrent with upper endoscopy. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2004 Nov:60(5):827-33 [PubMed PMID: 15557970]

Chirica M, Resche-Rigon M, Pariente B, Fieux F, Sabatier F, Loiseaux F, Munoz-Bongrand N, Gornet JM, Brette MD, Sarfati E, Azoulay E, Zagdanski AM, Cattan P. Computed tomography evaluation of high-grade esophageal necrosis after corrosive ingestion to avoid unnecessary esophagectomy. Surgical endoscopy. 2015 Jun:29(6):1452-61. doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-3823-0. Epub 2014 Aug 27 [PubMed PMID: 25159655]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBruzzi M, Chirica M, Resche-Rigon M, Corte H, Voron T, Sarfati E, Zagdanski AM, Cattan P. Emergency Computed Tomography Predicts Caustic Esophageal Stricture Formation. Annals of surgery. 2019 Jul:270(1):109-114. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002732. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29533267]

Lurie Y, Slotky M, Fischer D, Shreter R, Bentur Y. The role of chest and abdominal computed tomography in assessing the severity of acute corrosive ingestion. Clinical toxicology (Philadelphia, Pa.). 2013 Nov:51(9):834-7. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2013.837171. Epub 2013 Sep 13 [PubMed PMID: 24032468]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBentur Y, Slotky M, Fischer D, Shreter R, Lurie Y. The role of chest and abdominal computed tomography in assessing the severity of acute corrosive ingestion. Clinical toxicology (Philadelphia, Pa.). 2014 Jan:52(1):83. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2013.869339. Epub 2013 Dec 19 [PubMed PMID: 24350559]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBahrami-Motlagh H, Hadizadeh-Neisanghalb M, Peyvandi H. Diagnostic Accuracy of Computed Tomography Scan in Detection of Upper Gastrointestinal Tract Injuries Following Caustic Ingestion. Emergency (Tehran, Iran). 2017:5(1):e61 [PubMed PMID: 28894776]

Homan CS, Maitra SR, Lane BP, Thode HC Jr, Davidson L. Histopathologic evaluation of the therapeutic efficacy of water and milk dilution for esophageal acid injury. Academic emergency medicine : official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. 1995 Jul:2(7):587-91 [PubMed PMID: 8521203]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHoman CS, Maitra SR, Lane BP, Thode HC, Sable M. Therapeutic effects of water and milk for acute alkali injury of the esophagus. Annals of emergency medicine. 1994 Jul:24(1):14-20 [PubMed PMID: 8010543]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChobanian SJ. Accidental ingestion of liquid zinc chloride: local and systemic effects. Annals of emergency medicine. 1981 Feb:10(2):91-3 [PubMed PMID: 6784611]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSinger AJ, Mofenson HC, Caraccio TR, Ilasi J. Mercuric chloride poisoning due to ingestion of a stool fixative. Journal of toxicology. Clinical toxicology. 1994:32(5):577-82 [PubMed PMID: 7932917]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYoshida M, Satoh H, Igarashi M, Akashi K, Yamamura Y, Yoshida K. Acute mercury poisoning by intentional ingestion of mercuric chloride. The Tohoku journal of experimental medicine. 1997 Aug:182(4):347-52 [PubMed PMID: 9352627]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCakal B, Akbal E, Köklü S, Babalı A, Koçak E, Taş A. Acute therapy with intravenous omeprazole on caustic esophageal injury: a prospective case series. Diseases of the esophagus : official journal of the International Society for Diseases of the Esophagus. 2013 Jan:26(1):22-6. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2011.01319.x. Epub 2012 Feb 14 [PubMed PMID: 22332893]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHawkins DB, Demeter MJ, Barnett TE. Caustic ingestion: controversies in management. A review of 214 cases. The Laryngoscope. 1980 Jan:90(1):98-109 [PubMed PMID: 7356772]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMamede RC, De Mello Filho FV. Treatment of caustic ingestion: an analysis of 239 cases. Diseases of the esophagus : official journal of the International Society for Diseases of the Esophagus. 2002:15(3):210-3 [PubMed PMID: 12444992]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKochhar R, Poornachandra KS, Puri P, Dutta U, Sinha SK, Sethy PK, Wig JD, Nagi B, Singh K. Comparative evaluation of nasoenteral feeding and jejunostomy feeding in acute corrosive injury: a retrospective analysis. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2009 Nov:70(5):874-80. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.03.009. Epub 2009 Jul 1 [PubMed PMID: 19573868]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceShikowitz MJ, Levy J, Villano D, Graver LM, Pochaczevsky R. Speech and swallowing rehabilitation following devastating caustic ingestion: techniques and indicators for success. The Laryngoscope. 1996 Feb:106(2 Pt 2 Suppl 78):1-12 [PubMed PMID: 8569409]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJain AL, Robertson GJ, Rudis MI. Surgical issues in the poisoned patient. Emergency medicine clinics of North America. 2003 Nov:21(4):1117-44 [PubMed PMID: 14708821]

Anderson KD, Rouse TM, Randolph JG. A controlled trial of corticosteroids in children with corrosive injury of the esophagus. The New England journal of medicine. 1990 Sep 6:323(10):637-40 [PubMed PMID: 2200966]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceFulton JA, Hoffman RS. Steroids in second degree caustic burns of the esophagus: a systematic pooled analysis of fifty years of human data: 1956-2006. Clinical toxicology (Philadelphia, Pa.). 2007 May:45(4):402-8 [PubMed PMID: 17486482]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePelclová D, Navrátil T. Do corticosteroids prevent oesophageal stricture after corrosive ingestion? Toxicological reviews. 2005:24(2):125-9 [PubMed PMID: 16180932]

Usta M, Erkan T, Cokugras FC, Urganci N, Onal Z, Gulcan M, Kutlu T. High doses of methylprednisolone in the management of caustic esophageal burns. Pediatrics. 2014 Jun:133(6):E1518-24 [PubMed PMID: 24864182]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBoukthir S, Fetni I, Mrad SM, Mongalgi MA, Debbabi A, Barsaoui S. [High doses of steroids in the management of caustic esophageal burns in children]. Archives de pediatrie : organe officiel de la Societe francaise de pediatrie. 2004 Jan:11(1):13-7 [PubMed PMID: 14700754]

Tiryaki T, Livanelioğlu Z, Atayurt H. Early bougienage for relief of stricture formation following caustic esophageal burns. Pediatric surgery international. 2005 Feb:21(2):78-80 [PubMed PMID: 15619090]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBerkovits RN, Bos CE, Wijburg FA, Holzki J. Caustic injury of the oesophagus. Sixteen years experience, and introduction of a new model oesophageal stent. The Journal of laryngology and otology. 1996 Nov:110(11):1041-5 [PubMed PMID: 8944879]

Zhou JH, Jiang YG, Wang RW, Lin YD, Gong TQ, Zhao YP, Ma Z, Tan QY. Management of corrosive esophageal burns in 149 cases. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2005 Aug:130(2):449-55 [PubMed PMID: 16077412]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWang RW, Zhou JH, Jiang YG, Fan SZ, Gong TQ, Zhao YP, Tan QY, Lin YD. Prevention of stricture with intraluminal stenting through laparotomy after corrosive esophageal burns. European journal of cardio-thoracic surgery : official journal of the European Association for Cardio-thoracic Surgery. 2006 Aug:30(2):207-11 [PubMed PMID: 16829082]

Günel E, Cağlayan F, Cağlayan O, Canbilen A, Tosun M. Effect of antioxidant therapy on collagen synthesis in corrosive esophageal burns. Pediatric surgery international. 2002 Jan:18(1):24-7 [PubMed PMID: 11793058]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYukselen V, Karaoglu AO, Ozutemiz O, Yenisey C, Tuncyurek M. Ketotifen ameliorates development of fibrosis in alkali burns of the esophagus. Pediatric surgery international. 2004 Jun:20(6):429-33 [PubMed PMID: 15108014]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDemirbilek S, Aydin G, Yücesan S, Vural H, Bitiren M. Polyunsaturated phosphatidylcholine lowers collagen deposition in a rat model of corrosive esophageal burn. European journal of pediatric surgery : official journal of Austrian Association of Pediatric Surgery ... [et al] = Zeitschrift fur Kinderchirurgie. 2002 Feb:12(1):8-12 [PubMed PMID: 11967752]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceOzçelik MF, Pekmezci S, Saribeyoğlu K, Unal E, Gümüştaş K, Doğusoy G. The effect of halofuginone, a specific inhibitor of collagen type 1 synthesis, in the prevention of esophageal strictures related to caustic injury. American journal of surgery. 2004 Feb:187(2):257-60 [PubMed PMID: 14769315]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDuman L, Büyükyavuz BI, Altuntas I, Gökcimen A, Ceyhan L, Darici H, Aylak F, Tomruk O. The efficacy of single-dose 5-fluorouracil therapy in experimental caustic esophageal burn. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2011 Oct:46(10):1893-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2011.03.001. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22008323]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKaygusuz I, Celik O, Ozkaya O O, Yalçin S, Keleş E, Cetinkaya T. Effects of interferon-alpha-2b and octreotide on healing of esophageal corrosive burns. The Laryngoscope. 2001 Nov:111(11 Pt 1):1999-2004 [PubMed PMID: 11801986]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJaved A, Pal S, Krishnan EK, Sahni P, Chattopadhyay TK. Surgical management and outcomes of severe gastrointestinal injuries due to corrosive ingestion. World journal of gastrointestinal surgery. 2012 May 27:4(5):121-5. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v4.i5.121. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22655126]

Ryu HH, Jeung KW, Lee BK, Uhm JH, Park YH, Shin MH, Kim HL, Heo T, Min YI. Caustic injury: can CT grading system enable prediction of esophageal stricture? Clinical toxicology (Philadelphia, Pa.). 2010 Feb:48(2):137-42. doi: 10.3109/15563650903585929. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20199130]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceJudkins DG, Chen RJ, McTeer AV. Alkali Toxicity. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31334955]

Mensier A, Onimus T, Ernst O, Leroy C, Zerbib P. Evaluation of severe caustic gastritis by computed tomography and its impact on management. Journal of visceral surgery. 2020 Dec:157(6):469-474. doi: 10.1016/j.jviscsurg.2020.02.001. Epub 2020 Feb 20 [PubMed PMID: 32088182]

Faron M, Corte H, Poghosyan T, Bruzzi M, Voron T, Sarfati E, Cattan P, Chirica M. Quality of Life After Caustic Ingestion. Annals of surgery. 2021 Dec 1:274(6):e529-e534. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003774. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31972647]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceO'Grady M, Firth R, Roberts R. Intensive care unit utilisation post-oesophagectomy. The New Zealand medical journal. 2020 Feb 21:133(1510):56-61 [PubMed PMID: 32078601]

Findlay M, Purvis M, Venman R, Luong R, Carey S. Nutritional management of patients with oesophageal cancer throughout the treatment trajectory: benchmarking against best practice. Supportive care in cancer : official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer. 2020 Dec:28(12):5963-5971. doi: 10.1007/s00520-020-05416-x. Epub 2020 Apr 13 [PubMed PMID: 32281035]

Povilavičius J, Samalavičius NE, Verkauskas G, Trainavičius K, Povilavičienė M. Conservative treatment of caustic oesophageal injuries in children: 15 years of experience in a tertiary care paediatric centre. Przeglad gastroenterologiczny. 2019:14(4):286-291. doi: 10.5114/pg.2019.90255. Epub 2019 Dec 20 [PubMed PMID: 31988676]

Sharp CA, Swaithes L, Ellis B, Dziedzic K, Walsh N. Implementation research: making better use of evidence to improve healthcare. Rheumatology (Oxford, England). 2020 Aug 1:59(8):1799-1801. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keaa088. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32252071]

Labrague LJ, De Los Santos JAA, Falguera CC, Nwafor CE, Galabay JR, Rosales RA, Firmo CN. Predictors of nurses' turnover intention at one and five years' time. International nursing review. 2020 Jun:67(2):191-198. doi: 10.1111/inr.12581. Epub 2020 Mar 23 [PubMed PMID: 32202329]

Roy A, Druker S, Hoge EA, Brewer JA. Physician Anxiety and Burnout: Symptom Correlates and a Prospective Pilot Study of App-Delivered Mindfulness Training. JMIR mHealth and uHealth. 2020 Apr 1:8(4):e15608. doi: 10.2196/15608. Epub 2020 Apr 1 [PubMed PMID: 32234708]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMoore KA, O'Brien BC, Thomas LR. "I Wish They Had Asked": a Qualitative Study of Emotional Distress and Peer Support During Internship. Journal of general internal medicine. 2020 Dec:35(12):3443-3448. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-05803-4. Epub 2020 Mar 30 [PubMed PMID: 32232665]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence