Introduction

The thyroid gland is a small gland with significant effects. The mature thyroid gland is located in the neck and is responsible for delivering hormones to the body. Hormones released from the thyroid include thyroxine and calcitonin, which have an impact on the body's basal metabolic rate, heart, brain, muscle, digestive tract, and calcium homeostasis. The thyroid is the body's first endocrine gland to develop, with development beginning around the third week of gestation.

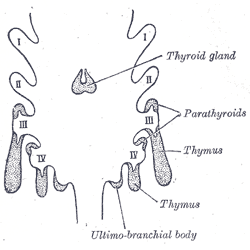

The thyroid arises from the pharyngeal pouches, which are composed of endoderm. Thyroid development begins as a diverticular outgrowth from the primitive pharynx. The diverticulum then descends inferiorly to reach its final destination in the neck. Traditionally, the thyroid is located inferior to the thyroid cartilage, approximately at the level of the C5-T1 vertebrae. During its descent, the thyroid connects to the tongue by the thyroglossal duct.[1]

Development

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Development

The thyroid originates between the first and second pharyngeal pouches near the base of the tongue. In the third week of gestation, around day 20-24, endodermal cells of the primitive pharynx proliferate, creating the thyroid diverticulum. Beginning in the fifth week of gestation, the thyroid diverticulum migrates caudally along the midline, crossing anteriorly to the hyoid bone and laryngeal cartilage. During migration, the thyroid remains attached to the tongue via the thyroglossal duct. In early descent, the thyroid is hollow but then solidifies during migration forming the follicular elements of the thyroid. Division of the thyroid into right and left lobes occurs in the fifth week of gestation.

Also, during the fifth week, the ultimobranchial bodies arise from the fourth/fifth pharyngeal pouches. The ultimobranchial bodies ultimately differentiate into the parafollicular C-cells, which play an essential role in calcium homeostasis. Traditionally, the parafollicular C-cells were thought to arise from neural crest cells, but recent works have disputed this by suggesting they arise from endoderm.[2] The ultimobranchial bodies fuse with the superior dorsolateral aspect of the developing thyroid, forming Zuckerkandl's tubercle.[3] The parafollicular C-cells then disseminate into the thyroid, but generally remain limited to the superolateral aspects of the thyroid, while the lower-third of the thyroid remains mostly devoid of C-cells. Fully developed C-cells secrete calcitonin, which decreases serum calcium by inhibiting osteoclast function.

By the seventh week of gestation, the thyroid has reached its final destination in the neck. Normally, the thyroglossal duct degenerates by the tenth week of gestation with only the foramen cecum to indicate its former existence. In some instances, incomplete obliteration of the duct can lead to abnormalities, including thyroglossal duct cysts, lingual thyroid, or a pyramidal lobe. Cellular differentiation and maturation then continue until the thyroid is functionally mature by the twelfth gestational week.

Pathophysiology

Pyramidal Lobe of the Thyroid (PL) - Pyramidal lobes occur when the distal portion of the thyroglossal duct differentiates into thyroid tissue. Estimates of pyramidal lobe incidence vary. For example, a 2015 study of 166 thyroidectomy patients found a pyramidal lobe in 65.7% of patients, with equal gender distribution, while a 2010 study of 90 male cadavers found a pyramidal lobe in 37.8% of patients.[4][5] Pyramidal lobes most commonly arise from the isthmus but can originate from either lobe (more often the left). They achieve variable lengths but are categorized as short (less than 15 mm), medium (15 to 30 mm) or long (greater than 30 mm), and are commonly longer in females than males. It is considered a normal anatomic variant and is generally asymptomatic.

Double Pyramidal Lobe (DPL) - An extremely rare variant with only a handful of cases reported. These present with two pyramidal lobes arising from the thyroid, often located at the junction of the isthmus and the right and left lobes, respectively. All case reports involve female patients aged 45 to 58 years old.[6][7]

Sub-Isthmic Accessory Gland - Another rare variant of thyroid development. Unlike pyramidal lobes which present superiorly to the thyroid gland, relating to the thyroid descent along the thyroglossal duct, these present inferiorly to the thyroid.[8]

Absent Isthmus - A normal thyroid isthmus is commonly located at the second and third tracheal rings, but can vary from the cricoid cartilage down to the fourth tracheal ring.[5] In rare cases, the isthmus is absent. While the right and left lobes are separated, they are often functional.[9]

Ectopic Thyroid Tissue - Thyroid tissue located outside the normal anatomic position in the anterior neck. It most commonly occurs secondary to failure of embryologic descent. The most common location for ectopic thyroid tissue is the base of the tongue (at the foramen cecum, secondary to failure or migration), but is also commonly found along the thyroglossal duct, resulting in a high cervical thyroid (due to incomplete migration). Excessive migration leads to superior mediastinal or pericardiac thyroid tissue. Less commonly, ectopic thyroid tissue can be found in the adrenal/pituitary glands along with the GI system, within the female reproductive system and even within the iris of the eye. One or more foci of ectopic tissue may be present. Ectopic thyroid tissue can be distinguished from thyroglossal duct cysts via thyroid scintigraphy, as ectopic tissue is functional, and cysts contain insufficient thyroid tissue for an examiner to identify.[10]

Lingual Thyroid - Rarely, the thyroid fails to descend properly down the thyroglossal duct to the final anatomic position, which leads to retention of thyroid tissue at the foramen cecum, at the base of the tongue, and is more common in female patients. Lingual thyroid can span a wide range of clinical presentations, from an incidental finding to partial airway obstruction. If symptomatic, lingual thyroid tissue can be surgically removed - with a risk of hypothyroidism if insufficient thyroid tissue remains.[11]

Thyroglossal Duct Cyst - Relatively rare, present in approximately 7% of the population worldwide. Arises when a portion of the thyroglossal duct fails to involute. Secretions from the epithelial lining result in inflammation and cyst formation. Thyroglossal cysts are found in the midline and closely associated with the hyoid bone, with 20 to 25% found suprahyoid and 25-65% infrahyoid. Cysts are frequently asymptomatic but can become infected and present as an abscess. Classically, thyroglossal duct cysts will elevate with swallowing or protrusion of the tongue.[12] Thyroglossal cysts are often confused with branchial cleft cysts, which arise from incomplete involution of pharyngeal clefts. The second cleft is the one most commonly implicated, but third and fourth pouches may also occur. Branchial cleft cysts typically present lateral to the midline, often anterior to the sternocleidomastoid. They do not elevate with swallowing or tongue protrusion.[13]

Lingual Cyst - This is a thyroglossal duct cyst occurring at the base of the tongue. These can present with difficulty in swallowing or breathing.[14]

Clinical Significance

Surgical significance of PL - A clinician discovers an existing pyramidal lobe pre-operatively only 50% of the time.[15] Because the pyramidal lobe (or DPL) is composed of normal thyroid tissue, it can harbor disease just like the 'normal' thyroid.[16] Thus, incomplete removal of an existing PL can lead to disease recurrence and re-operation.[4]

Surgical significance of Zuckerkandl's tubercle - A posterolateral extension of the thyroid with a close anatomic relationship with the recurrent laryngeal nerve, the inferior thyroid artery, and the parathyroid glands. Large tubercles can increase the risk of suboptimal and complicated surgeries.[3][17]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Allen E, Fingeret A. Anatomy, Head and Neck, Thyroid. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29262169]

Nilsson M, Williams D. On the Origin of Cells and Derivation of Thyroid Cancer: C Cell Story Revisited. European thyroid journal. 2016 Jul:5(2):79-93. doi: 10.1159/000447333. Epub 2016 Jun 24 [PubMed PMID: 27493881]

Chintamani. "Friend or Foe" of a Thyroid Surgeon?-the Tubercle of Zuckerkandl. The Indian journal of surgery. 2013 Oct:75(5):337-8. doi: 10.1007/s12262-013-0973-6. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24426472]

Gurleyik E, Gurleyik G, Dogan S, Cobek U, Cetin F, Onsal U. Pyramidal Lobe of the Thyroid Gland: Surgical Anatomy in Patients Undergoing Total Thyroidectomy. Anatomy research international. 2015:2015():384148. doi: 10.1155/2015/384148. Epub 2015 Jul 7 [PubMed PMID: 26236507]

Joshi SD, Joshi SS, Daimi SR, Athavale SA. The thyroid gland and its variations: a cadaveric study. Folia morphologica. 2010 Feb:69(1):47-50 [PubMed PMID: 20235050]

Gürleyik E. Double Pyramidal Lobe of the Thyroid Gland. Balkan medical journal. 2018 Jul 24:35(4):350-351. doi: 10.4274/balkanmedj.2017.1581. Epub 2018 Mar 28 [PubMed PMID: 29588265]

Kaklamanos I, Zarokosta M, Flessas I, Zoulamoglou M, Katsoulas T, Birbas K, Troupis T, Mariolis-Sapsakos T. Surgical anatomy of double pyramidal lobe on total thyroidectomy: a rare case report. Journal of surgical case reports. 2017 Mar:2017(3):rjx035. doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjx035. Epub 2017 Mar 1 [PubMed PMID: 28458845]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBhatnagar KP, Nettleton GS, Wagner CE. Subisthmic accessory thyroid gland in man: a case report and a review of thyroid anomalies. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 1997:10(5):341-4 [PubMed PMID: 9283734]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTaty-Anna K, Farihah HS, Norzana AG, Farida H, Das S. Absence of the isthmus of the thyroid gland: anatomical and clinical considerations. La Clinica terapeutica. 2012 Nov:163(6):503-4 [PubMed PMID: 23306746]

Alanazi SM, Limaiem F. Ectopic Thyroid. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30969714]

Marina Dj, Sajić S. [Lingual thyroid]. Srpski arhiv za celokupno lekarstvo. 2007 Mar-Apr:135(3-4):201-3 [PubMed PMID: 17642462]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAmos J, Shermetaro C. Thyroglossal Duct Cyst. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30085599]

Coste AH, Lofgren DH, Shermetaro C. Branchial Cleft Cyst. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29763089]

Karam O, Pfister RE, Extermann P, La Scala GC. Congenital lingual cysts. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2007 Apr:42(4):E25-7 [PubMed PMID: 17448749]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGeraci G, Pisello F, Li Volsi F, Modica G, Sciumè C. The importance of pyramidal lobe in thyroid surgery. Il Giornale di chirurgia. 2008 Nov-Dec:29(11-12):479-82 [PubMed PMID: 19068184]

Sinos G, Sakorafas GH. Pyramidal lobe of the thyroid: anatomical considerations of importance in thyroid cancer surgery. Oncology research and treatment. 2015:38(6):309-10. doi: 10.1159/000430894. Epub 2015 May 19 [PubMed PMID: 26045028]

Irkorucu O. Zuckerkandl tubercle in thyroid surgery: Is it a reality or a myth? Annals of medicine and surgery (2012). 2016 May:7():92-6. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2016.03.030. Epub 2016 Apr 6 [PubMed PMID: 27144005]