Introduction

Thoracotomy describes an incision made in the chest wall to access the contents of the thoracic cavity. Thoracotomies typically can be divided into two categories; anterolateral thoracotomies and posterolateral thoracotomies. These can be further subdivided into supra-mammary and infra-mammary and, of course, further divided into the right or left chest. Each type of incision has its utility given certain circumstances.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

The thoracic cavity hosts the heart, great vessels, lungs, esophagus, and trachea. The thoracic cavity is bordered by the thoracic outlet superiorly, the diaphragm inferiorly, the sternum anteriorly, and the vertebral bodies posteriorly. The thoracic cavity can be further subdivided into the pleural cavities and the mediastinum. The mediastinum and its contents are found within the center of the chest cavity and include the heart, great vessels, thymus, esophagus, and trachea. The pleural cavities enclose the parenchyma of the lungs. It is important for this discussion to note that the bulk of the heart lies mostly in the middle and to the left of the midline within the thoracic cavity.

Indications

Indications for thoracotomy most commonly include surgical treatment of distal aortic, cardiac, esophageal, and pulmonary diseases. The distal thoracic aortic disease may include dissection, rupture, or aneurysmal disease.[1] Cardiac diseases that may require thoracotomy incisions include congenital cardiac defects (atrial septal defect), valvular disease of the aortic, mitral, or tricuspid valve, specific locations of coronary artery disease, pericardial disease, and certain tumors of the heart and pericardium. Many of these indications for thoracotomy in the treatment of cardiac diseases may also be accessed with a median sternotomy, but when median sternotomy is deemed unsafe, a thoracotomy incision may be selected. Patients who would require re-do sternotomy are often deemed high risk for repeat sternotomy and may acquire the greatest benefit from alternative approaches.[2][3] Pulmonary diseases are most commonly treated with video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS), but many pulmonary diseases requiring operative interventions can be approached via a thoracotomy as well. These may include pulmonary malignancy (primary or metastases), pleural malignancies, pneumothoraces, or empyema. Esophageal disease that may be treated via thoracotomy incision includes but is not limited to esophageal cancer in adults and tracheoesophageal fistulas in infants. Right-sided thoracotomy is best for disease processes affecting the mid-esophagus, and left-sided thoracotomy may allow for better access to the distal esophagus. A trans-hiatal approach may be used, as well.

Contraindications

Contraindications to thoracotomy can be absolute or relative and depend upon the circumstances surrounding a thoracotomy. Thoracotomy may be contraindicated in patients who have had prior thoracotomy in the planned location, making re-entry unsafe, who are too frail to undergo anesthesia and in patients who will derive no benefit from operative intervention.

Equipment

The following equipment is necessary for thoracotomy: scalpel, long curved Mayo scissors, Finochietto retractor, long curved Metzenbaum scissors, long tissue forceps, curved hemostats, electrocautery, toothed forceps. Other materials may be required for the subsequent planned operative intervention and are not listed here. All anticipated equipment needed for an operation should be available prior to thoracotomy.

Personnel

Surgeon, anesthesiologist, scrub nurse or tech, and circulating nurse are some of the personnel needed for a thoracotomy. Other personnel may include a surgical assistant, resident, or fellow.

Preparation

Preoperative evaluation for patients undergoing surgery via thoracotomy is specific to their particular disease process and will not be discussed here. Preoperative evaluation, however, may be much less intensive if the thoracotomy is for an emergent indication. Imaging may play a key role in the determination of whether or not a patient will be best served with thoracotomy or sternotomy incision and is particularly helpful in the evaluation of patients with previous sternotomy incisions.[4] Preparation, specifically patient positioning, will be discussed below for supra-mammary anterolateral thoracotomy, infra-mammary anterolateral thoracotomy, and posterolateral thoracotomy. Important universal steps in preparation for thoracotomy include completion of the preoperative surgical checklist and preparation of patient skin from the chin to the toes with either an iodine or chlorhexidine gluconate solution.[5][6]

Technique or Treatment

For a supra-mammary anterolateral thoracotomy, the patient will need to be placed with their ipsilateral side elevated approximately 30 to 45 degrees. The ipsilateral arm is positioned at the patient's side. The thoracotomy incision is made between the second and third ribs along the superior border of the third rib. The pectoralis major and minor muscles are divided with electrocautery. Intercostal musculature is divided along the superior border of the rib in order to prevent damage to the neurovascular bundle that runs along the inferior border of the ribs. At this stage, the third rib may be detached from the sternum with an oscillating saw and moved for a better view of the operative field, or a thoracoscope may be used, allowing for the avoidance of rib resection. It is important to note that the internal mammary artery will need to be visualized and ligated to prevent hemorrhage obscuring the field of vision. In order to perform a submammary anterolateral thoracotomy, the patient will need to be positioned similarly to the supra-mammary thoracotomy position with the ipsilateral side elevated between 30 and 45 degrees and the ipsilateral arm at the patient's side.[7] A scalpel is used to sharply divide the skin along the inframammary crease overlying the fifth rib. Electrocautery is then used to divide the pectoralis major muscle and serratus anterior muscle. Visualization of the proper operative field can be achieved with the preservation and retraction of the latissimus dorsi, so it is preferable to retract instead of dividing this muscle. Either the fourth or fifth intercostal space is then entered after the division of intercostal muscles above the rib to ensure the preservation of the neurovascular bundle. To perform a posterolateral thoracotomy requires the patient to be positioned in the lateral decubitus position. Once the patient is properly secured to the operating table, the ipsilateral arm is raised and positioned anteriorly and cephalad to rest above the head. The incision is started along the inframammary crease and extended posterolaterally below the tip of the scapula. It is then extended superiorly between the spine and the edge of the scapula, a short distance. The trapezius muscle and the subcutaneous tissues are divided with electrocautery. The serratus anterior and latissimus dorsi muscles are identified and can be retracted. The intercostal muscles are then divided along the superior border of the ribs, and the thoracic cavity is accessed. Additionally, a vertical midaxillary incision may be made for muscle-sparing thoracotomy.[8] This technique involves placing the patient in the lateral decubitus position with the ipsilateral arm abducted to 90 degrees. A midaxillary vertical incision is made from just beneath the axillary hairline to approximately the ninth intercostal space, and the skin and subcutaneous tissues are divided. Dissection of the subcutaneous space continues until the posterior border of the serratus anterior, and the posterior border of the latissimus dorsi is visualized. A retractor is used to retract the latissimus dorsi posteriorly. The rib attachments of the serratus anterior muscle are detached until the appropriate intercostal space has adequate exposure. The intercostal muscles are then divided along the superior border of the inferior rib, and a rib spreader is applied.

Complications

Complications of thoracotomy include but are not limited to bleeding, infection, pneumothorax, pleural effusion, shoulder dysfunction, pain, and post-thoracotomy pain syndrome.[9][10] Bleeding can be serious and may be encountered during any of the incisional approaches discussed if care is not taken to preserve the neurovascular bundle along the inferior aspect of the ribs. Bleeding can also occur and be a serious complication during the right supra-mammary anterolateral thoracotomy approach if the internal mammary arteries are not properly identified. Infection is a possible complication and can be a soft tissue infection of the incisional site, the development of pneumonia, or the development of empyema. Another potential complication may be the development of a pneumothorax if the pleura and lung parenchyma are damaged. The development of pleural effusions is another complication that would not be unusual to see in a thoracotomy patient. Often drainage tubes are left in place after thoracotomy procedures to help prevent this complication. Incisional pain is an expected postoperative finding but can be classified as a postoperative complication if there is damage to the costal neurovascular bundle while accessing or closing the thoracic cavity. Post-thoracotomy pain syndrome is defined as pain along the thoracotomy incision site that persists for greater than two months after the operation.[11] Shoulder dysfunction is caused by the division of neurovascular bundles and musculature in traditional non-muscle sparing thoracotomy incisions.[9] Incisional pain can lead to splinting and decreased inspiratory and coughing efforts. Each of these puts a patient at greater risk of developing infectious complications.[10]

Clinical Significance

Most patients undergoing non-emergent thoracotomy incision, whether for cardiac or thoracic operative interventions, will have multiple comorbidities and are more likely to be frail. The procedures they will have via thoracotomy incision will decrease their cardiopulmonary reserve in a significant manner putting them at increased risk for postoperative complications resulting in a potentially higher rate of morbidity and mortality. In caring for a patient with a thoracotomy, it is critical to understand this and to know that the details in patient care may make a substantial difference in the clinical outcome for the patient.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

When caring for a patient who will undergo thoracotomy for any number of procedures, or who has just had a thoracotomy performed on them, it is critical to understand why that patient has the incision they do. The incision type alone can be a clue to the type of procedure performed and should serve as a marker for the severity of the illness to the team caring for the patient, alerting them that this patient is at high risk for complications. In caring for these patients, it is critical that teams communicate clearly and frequently, especially if any concerning features arise. These patients, prior to their procedure, will likely have seen a primary care doctor, a thoracic surgeon, an anesthesiologist, nurses, and, if appropriate, a cardiologist as well.[12] Intraoperatively a team composed of a surgeon, anesthesiology team, scrub and circulating nurse, and numerous others will care for a patient. Lastly, in the postoperative setting, a patient will be cared for by nurses, physicians, respiratory therapists, occupational/physical therapists, pharmacists, and more. It is the responsibility of each person on this interprofessional team to discuss concerns as they arise and to do their best to understand their role in patient care and recovery.

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Interventions

Preoperatively patients can be optimized with simple measures such as smoking cessation. Intraoperatively proper technique and excellent decision making will best help the patient. Recovery for thoracotomy patients can be improved and hastened with attention to detail postoperatively. Key interventions that seem simple and may be easy to neglect will greatly benefit them. These include appropriate and timely use of pain medication, frequent and proper use of incentive spirometry, ambulation in hallways, regular work with physical therapy and occupational therapy if necessary, and attention to detail while caring for patient incision sites.[13]

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Monitoring

Especially during the postoperative care of a thoracotomy, patient attention must be placed particularly on respiratory status (oxygenation, respiratory rate, respiratory effort, etc.) and cardiovascular status (rhythm, rate, blood pressure, etc.). As with any postoperative patient, attention to detail while performing incisional care is of utmost importance. It is important to note the state of the incisional site (erythema, discoloration, discharge, drainage, temperature, pain, etc.) and note any changes that occur from day-to-day.[14]

Media

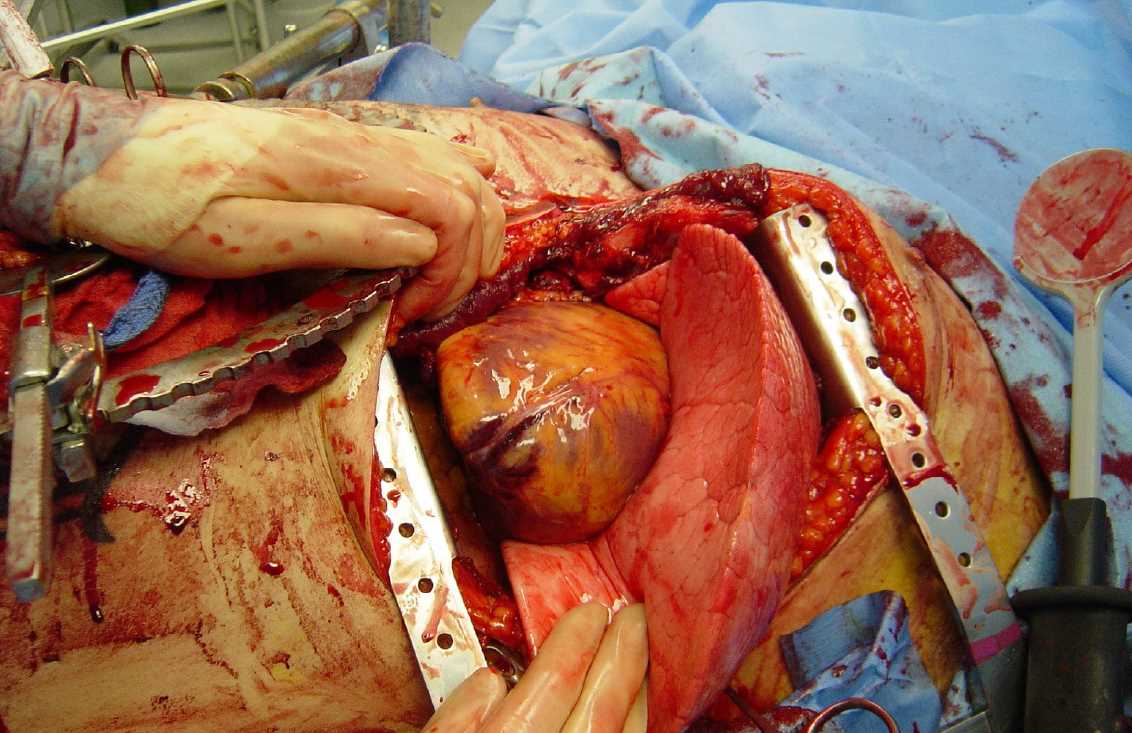

(Click Image to Enlarge)

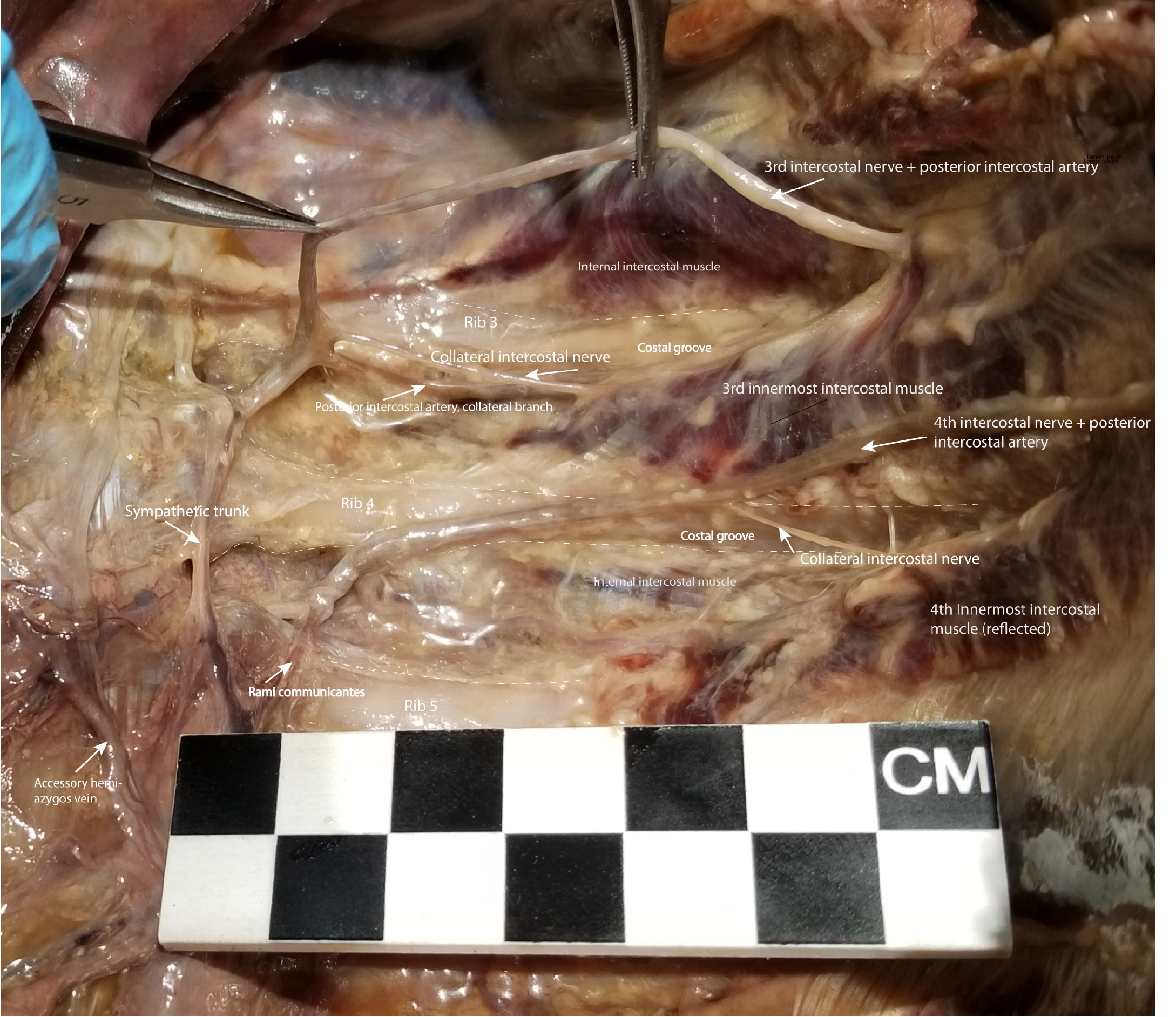

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Dissection of the Left Posterior Thoracic Wall Showing Intercostal Spaces 3 and 4. The intercostal neurovascular bundle, including intercostal nerve 3, has been elevated from its location in the costal groove to demonstrate the branching of the collateral intercostal nerve near the angle of the rib. The collateral intercostal nerve is subject to injury in thoracotomy in its location immediately superior to the rib. To avoid injuring the intercostal nerve or its collateral branch, the optimal entry point surgically into the intercostal space is midway between its superior and inferior borders.

Contributed by NT Boaz, MD. Dissection by K Meshida, R Bernor, and NT Boaz, MD

References

Frederick JR, Woo YJ. Thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm. Annals of cardiothoracic surgery. 2012 Sep:1(3):277-85. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2225-319X.2012.09.01. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23977509]

Cao H, Zhou Q, Fan F, Xue Y, Pan J, Wang D. Right anterolateral thoracotomy: an attractive alternative to repeat sternotomy for high-risk patients undergoing reoperative mitral and tricuspid valve surgery. Journal of cardiothoracic surgery. 2017 Sep 21:12(1):85. doi: 10.1186/s13019-017-0645-x. Epub 2017 Sep 21 [PubMed PMID: 28934975]

Romano MA, Haft JW, Pagani FD, Bolling SF. Beating heart surgery via right thoracotomy for reoperative mitral valve surgery: a safe and effective operative alternative. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2012 Aug:144(2):334-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.09.026. Epub 2011 Nov 3 [PubMed PMID: 22050983]

Park CB, Suri RM, Burkhart HM, Greason KL, Dearani JA, Schaff HV, Sundt TM 3rd. Identifying patients at particular risk of injury during repeat sternotomy: analysis of 2555 cardiac reoperations. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2010 Nov:140(5):1028-35. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.07.086. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20951254]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHaynes AB, Weiser TG, Berry WR, Lipsitz SR, Breizat AH, Dellinger EP, Herbosa T, Joseph S, Kibatala PL, Lapitan MC, Merry AF, Moorthy K, Reznick RK, Taylor B, Gawande AA, Safe Surgery Saves Lives Study Group. A surgical safety checklist to reduce morbidity and mortality in a global population. The New England journal of medicine. 2009 Jan 29:360(5):491-9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0810119. Epub 2009 Jan 14 [PubMed PMID: 19144931]

Edmiston CE Jr, Bruden B, Rucinski MC, Henen C, Graham MB, Lewis BL. Reducing the risk of surgical site infections: does chlorhexidine gluconate provide a risk reduction benefit? American journal of infection control. 2013 May:41(5 Suppl):S49-55. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2012.10.030. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23622749]

Holman WL, Goldberg SP, Early LJ, McGiffin DC, Kirklin JK, Cho DH, Pacifico AD. Right thoracotomy for mitral reoperation: analysis of technique and outcome. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2000 Dec:70(6):1970-3 [PubMed PMID: 11156104]

Ginsberg RJ. Alternative (muscle-sparing) incisions in thoracic surgery. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 1993 Sep:56(3):752-4 [PubMed PMID: 8379788]

Sakakura N, Mizuno T, Arimura T, Kuroda H, Sakao Y. Design variations in vertical muscle-sparing thoracotomy. Journal of thoracic disease. 2018 Aug:10(8):5115-5119. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2018.07.100. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30233887]

Reid JC, Jamieson A, Bond J, Versi BM, Nagar A, Ng BH, Moreland JD. A pilot study of the incidence of post-thoracotomy pulmonary complications and the effectiveness of pre-thoracotomy physiotherapy patient education. Physiotherapy Canada. Physiotherapie Canada. 2010 Winter:62(1):66-74. doi: 10.3138/physio.62.1.66. Epub 2010 Feb 22 [PubMed PMID: 21197180]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKarmakar MK, Ho AM. Postthoracotomy pain syndrome. Thoracic surgery clinics. 2004 Aug:14(3):345-52 [PubMed PMID: 15382766]

Brunelli A. Preoperative functional workup for patients with advanced lung cancer. Journal of thoracic disease. 2016 Nov:8(Suppl 11):S840-S848 [PubMed PMID: 27942405]

Brocki BC, Andreasen JJ, Langer D, Souza DS, Westerdahl E. Postoperative inspiratory muscle training in addition to breathing exercises and early mobilization improves oxygenation in high-risk patients after lung cancer surgery: a randomized controlled trial. European journal of cardio-thoracic surgery : official journal of the European Association for Cardio-thoracic Surgery. 2016 May:49(5):1483-91. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezv359. Epub 2015 Oct 20 [PubMed PMID: 26489835]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSanger PC, Simianu VV, Gaskill CE, Armstrong CA, Hartzler AL, Lordon RJ, Lober WB, Evans HL. Diagnosing Surgical Site Infection Using Wound Photography: A Scenario-Based Study. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2017 Jan:224(1):8-15.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2016.10.027. Epub 2016 Oct 14 [PubMed PMID: 27746223]

Al-Githmi IS,Alotaibi A,Habeebullah A,Bajunaid W,Jar S,Alharbi NA,Aziz H, Postoperative Pulmonary Complications in Patients Undergoing Elective Thoracotomy Versus Thoracoscopic Surgeries. Cureus. 2023 Sep; [PubMed PMID: 37849610]