Introduction

Lymphatic ducts empty lymph fluid into the venous system. The two lymphatic ducts of the body are the right lymphatic duct and the thoracic duct. The thoracic duct is the larger of the two and responsible for lymph drainage from the entire body except for the right sides of the head and neck, the right side of the thorax, and the right upper extremity which are primarily drained by the right lymphatic duct.[1][2]

Structure and Course

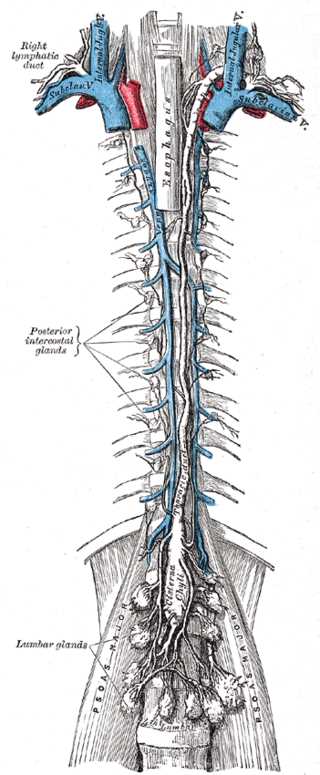

The thoracic duct is 38 to 45 centimeters long and 2 to 5 millimeters in diameter. It runs from the superior aspect of the cisterna chyli, a lymph sac at the L2 vertebral level, to the lower cervical spine. From the cisterna chyli, the duct continues superiorly, running between the aorta and the azygos vein and anterior to the vertebral column. The thoracic duct ascends through the aortic hiatus of the diaphragm entering the posterior mediastinum, still to the right of the vertebral column. It courses posterior to the esophagus at the T7 level and crosses over the midline to the left side of the thorax around the T5 vertebral level. As it continues upward, it runs behind the aorta and to the left of the esophagus ascending 2-3 cm above the clavicle. In the superior mediastinum, it passes behind the left common carotid artery, the vagus nerve, and the internal jugular vein. It then descends to empty into the junction of the left subclavian and internal jugular veins.

The wall of the thoracic duct has three layers: the intima, the media, and the adventitia. It also has a basement membrane. The media is composed of smooth muscle and connective tissue. The smooth muscle contracts regularly to move lymph flow forward. The thoracic duct also contains valves which may be unicuspid, bicuspid, or tricuspid, but are usually bicuspid. At the junction of the lymphatic and venous system, a bicuspid valve prevents venous backflow into the lymphatic system.[3]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The function of the thoracic duct is to transport lymph back into the circulatory system. Interstitial fluid is collected by lymph capillaries from the interstitial space. Lymph then moves through lymphatic vessels to lymph nodes. Lymphatic vessels merge to create the lymphatic ducts which drain into the venous system. The thoracic duct delivers an estimated 1.38 mL/kg/hour of lymph to the venous system.

Embryology

During the sixth week of development of the human embryo, the early lymphatic system is composed of blunt buds near the base of the neck. Six lymph sacs form by the end of the embryonic period. These lymph sacs are the cisterna chyli, two jugular lymph sacs, two iliac lymph sacs, and a retroperitoneal lymph sac. Lymphatic vessels develop to connect these sacs and form the early lymphatic system. The thoracic duct develops from lymphatic trunks on either side of the aorta that anastomoses to form a channel from the jugular lymph sacs to the cisterna chyli. Trunks continue to anastomose and enlarge, forming embryonic right and left thoracic ducts. The adult thoracic duct is derived from both of these embryonic thoracic ducts. The right primitive thoracic duct eventually develops into the lower adult thoracic duct whereas the left primitive thoracic duct develops into the upper portion of the adult thoracic duct.

Physiologic Variants

The typical anatomy described above is present in only about 50% of individuals. There are many anatomic variations of the thoracic duct. A cisterna chyli is present in about half of individuals. When embryologic lymphatic trunks converge above the T12 vertebral level, the cisterna chyli is generally absent, but there may be dilation of lower lumbar trunks.

In the embryo, portions of a bilateral system of lymphatic trunks anastomose and develop while portions atrophy. Failure of the typical pattern leads to anatomic variations of the thoracic duct. A common variation is a bifid lower aspect of the trunk caused by embryonic right and left lymphatic trunks failing to fuse. Another variation is the lower thoracic duct being replaced by a plexus of lymphatic vessels and forming a single duct higher in the mediastinum. Two rare variations include complete bilateral thoracic ducts and termination of the duct into the azygos system.

Variations in termination also exist. In the majority of cases, the duct terminates on the left side. In 2% to 3% of cases, the duct empties on the right, and bilaterally in up to 1.5% of cases. In over 95% of cases, the thoracic duct terminates in the internal jugular vein, the subclavian vein, or the angle between the two. The remaining 5% include termination in the external jugular vein, vertebral vein, brachiocephalic vein, suprascapular vein, and transverse cervical vein. The thoracic duct can also terminate as a single vessel (up to 87.5%), bilateral ducts (up to 25%), or several terminal branches (up to 7%).

The thoracic duct displays physiologic adaptation to certain disease processes by increasing in diameter. These disease states include congestive heart failure, cirrhosis or the liver, portal hypertension, and malignancy.[4][5]

Surgical Considerations

Procedures within the thoracic cavity risk injuring or obstructing the duct which could result in chylothorax. The long course of the thoracic duct predisposes it to traumatic injury during thoracic, cardiac, or head and neck surgeries. Frequent physiologic variants also make avoiding the duct during surgery somewhat difficult. The thoracic duct is particularly vulnerable to trauma during esophageal surgery. Certain noninvasive procedures also risk iatrogenic duct injury such as a central line placement. Occlusion of the thoracic duct also results in chylous extravasation although this is much less common compared to injury.

Dietary changes, including decreasing intake of fat and increasing intake of medium chain triglycerides, can be used as an initial conservative approach to treating low chyle output of less than 1 L/day. Bowel rest and lipid-free total parenteral nutrition is another option. If chyle output is over 1 L/day, thoracic duct ligation or percutaneous embolization must be considered.

Clinical Significance

As a central structure to lymphatic flow and movement, thoracic duct dysfunction and resulting chyle accumulation is concerning for malignancy. Lymph from organs can drain directly into the thoracic duct without passing a lymph node. This anodal route has been observed for the diaphragm, esophagus, and parts of the lungs. The drainage pattern may play a role in the prognosis of cancers of these organs. This pattern may also explain the presence of distant metastases without lymph node involvement.

The Virchow node, a lymph node located at the base of the neck where the duct generally terminates, can be enlarged in cases of malignancy and may obstruct drainage of the thoracic duct. When there is an obstruction of the thoracic duct, lymph collects in the pleural cavity. This formation of chylothorax can be the first sign of malignancy.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Rizvi S, Wehrle CJ, Law MA. Anatomy, Thorax, Mediastinum Superior and Great Vessels. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30137860]

Chaudhry SR, Bordoni B. Anatomy, Thorax, Esophagus. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29494119]

Ndiaye A, Di-Marino V, Ba PS, Ndiaye A, Gaye M, Nazarian S. Anatomical variations in lymphatic drainage of the right lung: applications in lung cancer surgery. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2016 Dec:38(10):1143-1151 [PubMed PMID: 27151087]

Sarkaria IS, Finley DJ, Bains MS, Adusumilli PS, Rizk NP, Huang J, Downey RJ, Rusch VW, Jones DR. Chylothorax and Recurrent Laryngeal Nerve Injury Associated With Robotic Video-Assisted Mediastinal Lymph Node Dissection. Innovations (Philadelphia, Pa.). 2015 May-Jun:10(3):170-3. doi: 10.1097/IMI.0000000000000160. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26165562]

Bryant AS, Minnich DJ, Wei B, Cerfolio RJ. The incidence and management of postoperative chylothorax after pulmonary resection and thoracic mediastinal lymph node dissection. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2014 Jul:98(1):232-5; discussion 235-7. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.03.003. Epub 2014 May 6 [PubMed PMID: 24811982]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence