Introduction

Sinus tachycardia is a regular cardiac rhythm in which the heart beats faster than normal and results in an increase in cardiac output. While it is common to have sinus tachycardia as a compensatory response to exercise or stress, it becomes concerning when it occurs at rest.[1] The normal resting heart rate for adults is between 60 and 100, which varies based on the level of fitness or the presence of medical comorbidities.[2][3] For children, it varies by age but is commonly higher than the resting rate in adults (starting approximately between 100 and 150 beats per minute in infancy with a gradual reduction over the next six years).[4]

The presence of tachycardia at rest could be the earliest sign of serious pathology. Thus, it is crucial for the clinician to rapidly identify the underlying cause of tachycardia and determine if it indicates urgent evaluation and/or treatment.[2] This activity will review the etiologies of tachycardia and approach to the patient who presents with tachycardia.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Tachycardia can have physiological or pathological causes. Physiologically it is commonly associated with catecholaminergic triggers, including exercise, stress, pain, and anxiety.[2] Pathologically, there are cardiac and non-cardiac etiologies as summarized below:

Cardiac etiologies:

*Supraventricular tachycardia is an arrhythmia originating above the ventricles as demonstrated by a narrow QRS complex on an electrocardiogram. If the rhythm is regular, atrial flutter, atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia (AVRT), atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia (AVNRT), atrial tachycardia, or sinus tachycardia are the common etiologies. If the rhythm is irregular atrial fibrillation, atrial tachycardia with variable block, atrial flutter with variable block, multifocal atrial tachycardia, or frequent premature atrial contractions should merit consideration.[5]

*Ventricular tachycardia is is an arrhythmia that originates in the ventricles as demonstrated by a wide QRS on an electrocardiogram. It can be nonsustained (lasting less than 30 seconds or sustained (lasting greater than 30 seconds or with associated hemodynamic instability). Additionally, if the QRS morphology is stable, it is classified as monomorphic, and if the PRS morphology is variable, it classifies as polymorphic.[6]

*Torsades de pointes is a characteristic form of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia that results from either a congenital or acquired prolonged QT interval. Risk factors for torsades de pointes include medications that prolong the QT interval, female gender, hypokalemia, hypocalcemia, hypomagnesemia, ischemia, and structural heart disease.[7][8]

*Myocarditis is an inflammatory process involving cardiac myocytes that is generally secondary to a viral infection. Other sources of myocarditis include bacterial and parasitic infection, ingestion of medication or recreational substance, hypersensitivity reactions to medications or venoms, autoimmune disease, sarcoidosis, hypothermia, ischemia, radiation, and rejection of a transplanted heart.[9]

*Cardiac tamponade is a collection of symptoms (traditionally hypotension, jugular venous distention, muffled heart sounds, pulses paradoxus, and interventricular septum bowing during inspiration) secondary to increased pressure in the pericardial space. This pressure increase results from a transudative, exudative, or sanguineous pericardial effusion. The effusion can be secondary to acute trauma, aortic dissection, intrathoracic neoplasm, recent procedures or instrumentation of the thorax, radiation therapy, autoimmune disease, myocardial infarction, medication, uremia, or infection.[10]

*Acute coronary syndrome is a collection of symptoms secondary to ischemic heart disease. It can present as unstable angina, non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), and ST-segment myocardial infarction (STEMI). Patients at elevated risk for acute coronary syndrome are patients with obesity, hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, age greater than 50 years, male gender, tobacco use, and a family history of heart disease.[11]

Non-cardiac pathologic etiologies:

Respiratory:

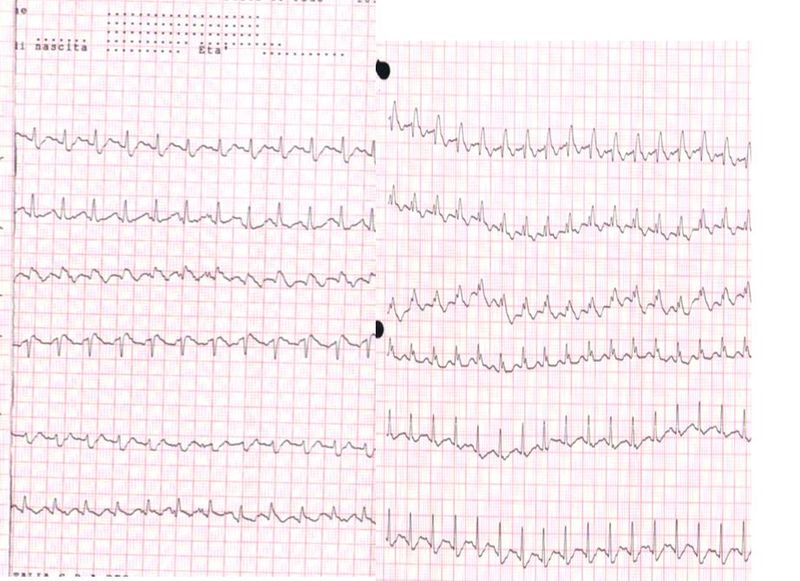

*Pulmonary Emboli are disorders of the pulmonary vasculature. They can be acute, chronic, or both.[12][13] Acute pulmonary emboli are generally more clinically significant and have higher rates of morbidity and mortality. Acute pulmonary emboli most often are a piece of a deep vein thrombus that has traveled through the circulation to the pulmonary vasculature, but fat emboli from an orthopedic injury, amniotic fluid emboli during pregnancy, and air emboli from instrumentation of central vasculature are all potential etiologies.[14][15][16][15][14] See Image. Electrocardiogram, Pulmonary Embolism.

*Hypoxia is a clinical state where tissues do not receive the necessary amount of oxygen to support their metabolic demand. Hypoxia can result from the inability to take in oxygen, transport the oxygen, or perform oxygen gas exchange.[17]

Gastrointestinal/Renal/Electrolyte:

*Hypoglycemia is the state when plasma glucose concentration falls below 70 mg/dL. It most commonly presents as a side effect of the medical therapies, i.e., drug-induced. It can also result from critical illness, alcohol consumption, hormonal imbalance, bariatric surgery, inborn errors of metabolism, insulinomas, and some pituitary and adrenal adenomas.[18]

*Dehydration results from an imbalance of the total body fluid intake and output. To maintain cardiac output in the setting of intravascular depletion, heart rate will increase.[19]

*Hyperkalemia is a potassium serum level greater than the standard accepted upper limit of normal (generally 5.0 to 5.5 mEq/L). Falsely elevated potassium levels, from sample hemolysis, is the most common cause of hyperkalemia. Additional etiologies include renal failure, rhabdomyolysis, excessive exercise, metabolic acidosis, insulin deficiency, tumor lysis syndrome, medication-induced, and increased intake of potassium.[20]

Hypomagnesemia is a serum magnesium level below 1.6 mg/dL. Hypomagnesemia can result from the low intake or poor absorption of magnesium, and increased filtration or excretion of magnesium. These can all be either congenital or acquired conditions. Acquired conditions that impact magnesium level include prolonged nasogastric suction, malabsorption, acute pancreatitis, refeeding syndrome, late-term pregnancy, lactation, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus with glucosuria or diabetes mellitus complicated by diabetic nephropathy, post-kidney injury diuresis, proximal tubule injury or medications that act on the proximal tubule, thick ascending loop of Henle, or descending loop of Henle.[21]

Hypocalcemia is a serum calcium level below 8.5 mg/dL. It can result from lack of sunlight exposure, nutritional deficiency, malabsorption, post-gastric bypass surgery, end-stage liver disease, chronic kidney disease, vitamin-D dependent rickets, hypomagnesemia, hyperphosphatemia, medications, rapid transfusion of large volumes of citrate-containing blood, acute critical illness, osteoblastic metastases, acute pancreatitis, rhabdomyolysis, and mitochondrial gene defects.[22]

Infectious Disease:

*Sepsis is a systemic inflammatory illness secondary to an infection that causes organ dysfunction and is a leading cause of mortality in the United States. It is a spectrum of illness and can present as mild, fulminant, or intermediate disease. In the early stages of sepsis, the large inflammatory burden will decrease systemic vascular resistance. The body compensates for decreased systemic vascular resistance by increasing heart rate, and patients (particularly pediatric patients) can be normotensive to hypertensive through this compensatory period.[23]

Vascular:

*Shock is an acute circulatory failure that provides insufficient tissue perfusion and hypoxia. There are four major types of shock- distributive, hypovolemic, cardiogenic, and obstructive. Distributive shock is characterized by decreased systemic vascular resistance and is secondary to sepsis, systemic inflammatory response syndrome, anaphylaxis, neurologic trauma, or endocrinologic pathology. Hypovolemic shock characteristically demonstrates intravascular volume depletion. It can be secondary to hemorrhage or dehydration. Cardiogenic shock is characterized by decreased cardiac output. Cardiogenic shock can be secondary to infarction-causing either large areas of ischemia in the ventricles, papillary muscle rupture, or ventricular septal rupture; infection of the myocardium; pericardial effusion, aortic dissection, acute arrhythmias; and cardiotoxic medications-particularly in an overdose. Obstructive shock is characterized by inappropriate cardiac output despite normovolemia and cardiac function. Common causes include tension pneumothorax, cardiac tamponade, restrictive cardiomyopathy, constrictive pericarditis, hemodynamically significant pulmonary emboli, coarctation of the aorta, or other cardiac outflow obstruction, restrictive cardiomyopathy, and severe pulmonary hypertension.[24]

Hematologic

*Hemorrhage is the disease process where a clinically significant amount of blood is lost after a blood vessel is damaged. There are four classes of hemorrhage. Class I is less than 15% of total blood volume. In general, there is no change to hemodynamics, and urine output is maintained. Class II is between 15 to 30% of total blood volume loss, and mild tachycardia (10 to 20% increase in baseline rate), hypotension, tachypnea, and decreased urine output are notable. Class III is 30 to 40% of total blood volume loss with associated tachycardia (20 to 40% increase), hypotension, tachypnea, and oliguria. Class IV is greater than 40% blood loss with significant tachycardia (40% pulse increase), hypotension, tachypnea, anuria, and lethargy.[25][26]

Anemia is a disease where the body does not have the appropriate amount of hemoglobin or red blood cells. Anemia can be acute or chronic and can divide into microcytic, normocytic, and macrocytic. Microcytic anemia can be secondary to iron deficiency, lead poisoning, or thalassemia. Normocytic anemia can be secondary to malignant processes, hemorrhage, hemolysis, chronic disease, aplastic anemia, or other bone marrow failure syndromes. Macrocytic anemia can be secondary to vitamin B12 or folate deficiency, hypothyroidism, medications, alcoholism, liver disease, or myelodysplastic syndromes.[25]

Toxicology:

*Ingestion of medications can cause tachycardia. The following are is a list of common medications that will result in tachycardia:

- Albuterol

- Amphetamines

- Anticholinergics

- Antihistamine

- Atropine

- Caffeine

- Carbon monoxide

- Cellular asphyxiants

- Chloral hydrate

- Clozapine

- Cocaine

- Dobutamine

- Dopamine

- Ephedrine

- Epinephrine

- Fluoride

- Levothyroxine

- Methylphenidate

- Phenothiazines

- Potassium

- Pseudoephedrine

- Scopolamine

- Theophylline

- Tricyclic antidepressants

*Withdrawal from substances or medications is an additional source of tachycardia. The following is a list of common medications that will result in tachycardia when discontinued:

- Alcohol

- Benzodiazepines

- Beta-blockers

- Calcium channel blockers

- Carbamates

- Clonidine

- Digitalis lanata

- Digitalis pupurea

- Digitoxin

- Digoxin

- Imidazoline

- Magnesium

- Oleander

- Opioids

- Organophosphates

- Phenylpropanolamine

- Red Squill

- Sedative-hypnotics

Endocrinologic:

Pregnancy results in many physiologic changes, including increased heart rate, cardiac output, and vascular volume.[27]

Hyperthyroidism is a condition secondary to excess thyroid hormone. It commonly presents with multisystem pathology, including palpitations, tachycardia, anxiety, tremor, diaphoresis, edema, hyperreflexia, weight loss, and changes to the skin and nails. Hyperthyroidism can also result in cardiac arrhythmias such as atrial fibrillation.[28]

Pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas are neuroendocrine tumors of the adrenal gland and extra-adrenal autonomic tissue, respectively. They present with tachycardia, diaphoresis, diarrhea, hypertension, weight loss, and anxiety.[29]

*denotes a life-threatening etiology

Epidemiology

Sinus tachycardia is a common, intermittent, and short-lived cardiac rhythm.[2][30] Inappropriate sinus tachycardia is a diagnosis of exclusion that occurs in patients without an underlying etiology for the sinus tachycardia.[31][32] It is thought to be a rare condition, often seen in young females and healthcare professionals.[31][32] Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome is also often seen in young females and is a common orthostatic disease seen after stress (i.e., sepsis, pregnancy, surgery, or trauma).[33][31][34]

History and Physical

Patients with sinus tachycardia are commonly asymptomatic, but the patient may be aware of the increased heartbeat and may complain of heart palpitations.[2] Depending on the underlying etiology, sinus tachycardia may correlate with other symptoms. This symptomatic presentation can include dyspnea, chest pain, lightheadedness, dizziness, syncope, and presyncope.[2] A detailed history is vital to decisions regarding the appropriate management of tachycardia. These include inquiring about precipitating factors (i.e., fever or exercise), recent medications, toxic exposures, drug or caffeine use, a history of illness, a history of heart disease or recent heart surgery, and family history.[35][36][35]

On physical exam, evaluation of the patient’s hemodynamic status is crucial to stabilization of the patient, particularly to ensure that the patient is not on the verge of cardiovascular collapse due to shock.[37] A cardiovascular examination is necessary to confirm the presence of tachycardia, and to evaluate for the presence of distant heart sounds (i.e., seen in pericardial effusions with tamponade), pulsus paradoxus, third or fourth heart sounds or gallop rhythm (i.e., seen in myocardial dysfunction), and murmurs (i.e., seen in structural heart disease).[35][10][38][39]

Evaluation

The evaluation of persistent sinus tachycardia at rest involves a careful assessment of first whether tachycardia is an appropriate response and then focus on identifying the underlying cause. The assessment can include an electrocardiogram, 24-hour Holter recording, pulse oximetry, echocardiogram, arterial blood gas, lactic acid level, chest radiograph, D-dimer, chest computed tomography with angiography,ventilation-perfusion scan, cardiac enzymes levels, glucose level, electrolytes, complete blood count, and/or a toxicology screen.

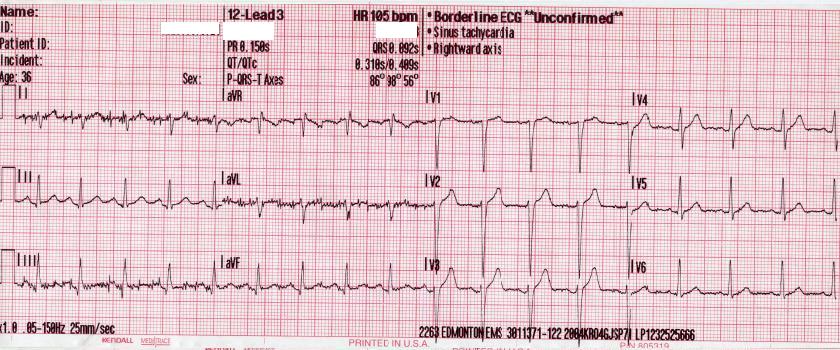

Clinicians often first perform an electrocardiogram to confirm the presence of sinus tachycardia and to rule out the presence of other tachydysrhythmias (see Image. Electrocardiogram, Sinus Tachycardia).[2] A 24-hour Holter recording can confirm the presence of inappropriate sinus tachycardia. Pulse oximetry is a quick way to identify hypoxia.[40] An echocardiogram can help to rule out cardiac failure.[41] Arterial blood gases are performed to determine the presence of acidity and if it is related to the level of carbon dioxide or metabolic derangement.[40] Lactic acid levels can determine the presence of tissue hypoperfusion.[42] A chest X-ray is useful to identify a source of infection, cardiac failure, or a pneumothorax.[41][43] D-dimer, chest computed tomography, and ventilation-perfusion scans can determine the presence of a pulmonary embolus.[44] Glucose and electrolyte levels can help identify metabolic derangements.[45] A complete blood count can help identify the presence of anemia and infection.[36] A toxicology screen can determine the presence of any prescription, illicit, and toxic substances that could elicit tachycardia, including cocaine or caffeine.[36][46]

Treatment / Management

The identification and treatment of the underlying etiology of sinus tachycardia is the cornerstone of management.[1] Benign causes such as physical activity or stress often do not require any specific cardiac treatment.[1] If sinus tachycardia is due to a medical condition at risk for clinical deterioration (i.e., sepsis, shock, hypoxia, metabolic acidosis, acute myocardial ischemia), the patient should be admitted for urgent evaluation. Treatment should carefully focus on the underlying cause.

Differential Diagnosis

Tachycardia requires differentiation from normal sinus rhythm and tachydysrhythmias. Sinus tachycardia presents with a regular rhythm with normal electrographic features: 1) presence of P waves that are upright in leads I, II and aVL, and negative in lead aVR; 2) each P wave is followed by a QRS and T waves and 3) a heart rate of greater than 100 beats per minute.[1] Normal sinus rhythm presents with the same electrographic features as sinus tachycardia, with the exception that the heart rate is between 60 and 100 beats per minute.[47] Supraventricular tachycardias present with a heart rate greater than 100 beats per minute and a narrow QRS (less than 120 milliseconds).[48] Atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia is an intermittent supraventricular tachycardia identified by its abrupt onset and termination. The ventricular heart rate is between 120 and 220 beats per minute, and abnormal P waves (when identified), ST depression, and T wave inversions can be present.[49] Atrial fibrillation presents with an irregularly regular rhythm, no discernible P waves, and could present with a rapid ventricular rate (above 100 beats per minute).[50] Typical atrial flutter presents with an absence of P waves, "sawtooth" flutter pattern.[51] Ventricular tachycardias have a wide QRS complex (greater than 120 milliseconds), can be polymorphic or monomorphic, with a heart rate greater than 100.[6]

Inappropriate sinus tachycardia is a chronic nonparoxysmal resting heart rate of more than 100 beats per minute that is not associated with any physiologic, pharmacologic, or pathologic etiology.[52] Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome is a cardiovascular response to postural changes. This condition occurs when the patient (typically in young females in the absence of structural heart disease) alter their position from recumbent to standing and have an increase in heart rate (30 beats per minute or higher for more than 30 seconds; greater than or equal to 40 beats per minute in patients aged between 12 and 19 years of age) in the absence of orthostatic vital sign changes.[53]

Following identification and confirmation of sinus tachycardia, the clinician must then determine the underlying cause starting by ruling out life-threatening cardiac and non-cardiac etiologies that require immediate evaluation and treatment.

Prognosis

Persistent sinus tachycardia at rest requires an evaluation by a medical professional. Early identification and intervention may result in favorable patient outcomes depending on the underlying etiology.[54][55][54] If sinus tachycardia is confirmed and determined to be transient due to a normal physiologic response to stress or anxiety, it often results in spontaneous resolution.[1]

Complications

Unrecognized persistent sinus tachycardia due to a pathologic cause can result in myocardial ischemia, reduced ventricular filling time, resulting in decreased cardiac output, end-organ system failure, cardiomyopathy, cardiac arrest, and death.[56]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients should understand that while tachycardia can be a normal physiologic response, it can be one of the first signs of serious medical illness. Patient education focused on the underlying etiology of tachycardia (particularly the associated symptoms) is essential to ensure proper management and follow up.

If any concerns regarding the presence of tachycardia with any associated symptoms (including chest pain or dyspnea), the patient should be advised to seek immediate medical attention.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Serious adverse events may result from unrecognized clinical deterioration; thus, an interprofessional team approach is necessary for diagnosis and management.[57] To improve its detection in hospitalized patients, various vital signs serve as part of an early warning system, which includes the heart rate.[58] The efficient use of these tools requires an integrated inter-professional team-based approach to facilitate communication between nursing and the medical team.[57][59][57] Bedside nurses must ensure timely and accurate entry of vital signs as well as recognition of important patient trends. [Level 1]

The patient's primary caregivers (which can include nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and physicians) must utilize the early warning scoring system, the patient’s heart rate and trends, and any historical and physical exam features to help identify and recognize any life-threatening causes early.[59] If the early warning scoring system identifies a clinically deteriorating patient, an interdisciplinary rapid response team (consisting of trained critical care unit physicians, nurses, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, respiratory therapists) may be triggered to evaluate and initiate treatment to prevent further decline urgently.[60] [Level 1]

Other disciplines may have involvement, depending on the etiology. Pharmacists may be involved to prepare and immediately deliver antimicrobial medications in patients suspected of sepsis.[61] Critical care teams may be involved earlier if the patient appears to be at risk of a hemodynamic compromise requiring close monitoring and emergent intervention.[62] Cardiologists might consult on the case if cardiac failure results from an underlying cause requiring further diagnostic workup and treatment.[63] [Level 2]

Interprofessional teamwork, communication, and collaboration are key to identify the presence of tachycardia and ensure patient safety. [Level 5]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Electrocardiogram, Pulmonary Embolism. The ECG of a patient with pulmonary embolism showed sinus tachycardia of approximately 150 bpm and a right bundle branch block.

Walter Serra, Giuseppe De Iaco, Claudio Reverberi, Tiziano Gherli, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Electrocardiogram, Sinus Tachycardia. Sinus Tachycardia is seen on ECG.

Glenlarson, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

References

Yusuf S, Camm AJ. The sinus tachycardias. Nature clinical practice. Cardiovascular medicine. 2005 Jan:2(1):44-52 [PubMed PMID: 16265342]

Yusuf S, Camm AJ. Deciphering the sinus tachycardias. Clinical cardiology. 2005 Jun:28(6):267-76 [PubMed PMID: 16028460]

KOSSMANN CE. The normal electrocardiogram. Circulation. 1953 Dec:8(6):920-36 [PubMed PMID: 13106913]

Fleming S, Thompson M, Stevens R, Heneghan C, Plüddemann A, Maconochie I, Tarassenko L, Mant D. Normal ranges of heart rate and respiratory rate in children from birth to 18 years of age: a systematic review of observational studies. Lancet (London, England). 2011 Mar 19:377(9770):1011-8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62226-X. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21411136]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBibas L, Levi M, Essebag V. Diagnosis and management of supraventricular tachycardias. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l'Association medicale canadienne. 2016 Dec 6:188(17-18):E466-E473. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.160079. Epub 2016 Oct 24 [PubMed PMID: 27777258]

Foth C, Gangwani MK, Ahmed I, Alvey H. Ventricular Tachycardia. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30422549]

Nachimuthu S, Assar MD, Schussler JM. Drug-induced QT interval prolongation: mechanisms and clinical management. Therapeutic advances in drug safety. 2012 Oct:3(5):241-53. doi: 10.1177/2042098612454283. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25083239]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSauer AJ, Newton-Cheh C. Clinical and genetic determinants of torsade de pointes risk. Circulation. 2012 Apr 3:125(13):1684-94. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.080887. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22474311]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBlauwet LA, Cooper LT. Myocarditis. Progress in cardiovascular diseases. 2010 Jan-Feb:52(4):274-88. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2009.11.006. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20109598]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceStashko E, Meer JM. Cardiac Tamponade. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28613742]

Kumar A, Cannon CP. Acute coronary syndromes: diagnosis and management, part I. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 2009 Oct:84(10):917-38. doi: 10.4065/84.10.917. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19797781]

Lavorini F, Di Bello V, De Rimini ML, Lucignani G, Marconi L, Palareti G, Pesavento R, Prisco D, Santini M, Sverzellati N, Palla A, Pistolesi M. Diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary embolism: a multidisciplinary approach. Multidisciplinary respiratory medicine. 2013 Dec 19:8(1):75. doi: 10.1186/2049-6958-8-75. Epub 2013 Dec 19 [PubMed PMID: 24354912]

Nishiyama KH, Saboo SS, Tanabe Y, Jasinowodolinski D, Landay MJ, Kay FU. Chronic pulmonary embolism: diagnosis. Cardiovascular diagnosis and therapy. 2018 Jun:8(3):253-271. doi: 10.21037/cdt.2018.01.09. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30057874]

Adeyinka A, Pierre L. Fat Embolism. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29763060]

Kaur K, Bhardwaj M, Kumar P, Singhal S, Singh T, Hooda S. Amniotic fluid embolism. Journal of anaesthesiology, clinical pharmacology. 2016 Apr-Jun:32(2):153-9. doi: 10.4103/0970-9185.173356. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27275041]

Gordy S, Rowell S. Vascular air embolism. International journal of critical illness and injury science. 2013 Jan:3(1):73-6. doi: 10.4103/2229-5151.109428. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23724390]

Cafaro RP. Hypoxia: Its Causes and Symptoms. Journal of the American Dental Society of Anesthesiology. 1960 Apr:7(4):4-8 [PubMed PMID: 19598857]

Mathew P, Thoppil D. Hypoglycemia. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30521262]

Popkin BM, D'Anci KE, Rosenberg IH. Water, hydration, and health. Nutrition reviews. 2010 Aug:68(8):439-58. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2010.00304.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20646222]

Simon LV, Hashmi MF, Farrell MW. Hyperkalemia. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29261936]

Pham PC, Pham PA, Pham SV, Pham PT, Pham PM, Pham PT. Hypomagnesemia: a clinical perspective. International journal of nephrology and renovascular disease. 2014:7():219-30. doi: 10.2147/IJNRD.S42054. Epub 2014 Jun 9 [PubMed PMID: 24966690]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFeingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, Boyce A, Chrousos G, Corpas E, de Herder WW, Dhatariya K, Dungan K, Hofland J, Kalra S, Kaltsas G, Kapoor N, Koch C, Kopp P, Korbonits M, Kovacs CS, Kuohung W, Laferrère B, Levy M, McGee EA, McLachlan R, Muzumdar R, Purnell J, Sahay R, Shah AS, Singer F, Sperling MA, Stratakis CA, Trence DL, Wilson DP, Schafer AL, Shoback DM. Hypocalcemia: Diagnosis and Treatment. Endotext. 2000:(): [PubMed PMID: 25905251]

Lever A, Mackenzie I. Sepsis: definition, epidemiology, and diagnosis. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2007 Oct 27:335(7625):879-83 [PubMed PMID: 17962288]

Haseer Koya H, Paul M. Shock. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30285387]

Johnson AB, Burns B. Hemorrhage. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31194413]

Gutierrez G, Reines HD, Wulf-Gutierrez ME. Clinical review: hemorrhagic shock. Critical care (London, England). 2004 Oct:8(5):373-81 [PubMed PMID: 15469601]

Klein HH, Pich S. [Cardiovascular changes during pregnancy]. Herz. 2003 May:28(3):173-4 [PubMed PMID: 12756474]

Reid JR, Wheeler SF. Hyperthyroidism: diagnosis and treatment. American family physician. 2005 Aug 15:72(4):623-30 [PubMed PMID: 16127951]

Asa SL, Ezzat S, Mete O. The Diagnosis and Clinical Significance of Paragangliomas in Unusual Locations. Journal of clinical medicine. 2018 Sep 13:7(9):. doi: 10.3390/jcm7090280. Epub 2018 Sep 13 [PubMed PMID: 30217041]

Olshansky B, Sullivan RM. Inappropriate sinus tachycardia. Europace : European pacing, arrhythmias, and cardiac electrophysiology : journal of the working groups on cardiac pacing, arrhythmias, and cardiac cellular electrophysiology of the European Society of Cardiology. 2019 Feb 1:21(2):194-207. doi: 10.1093/europace/euy128. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29931244]

Pellegrini CN, Scheinman MM. Epidemiology and definition of inappropriate sinus tachycardia. Journal of interventional cardiac electrophysiology : an international journal of arrhythmias and pacing. 2016 Jun:46(1):29-32. doi: 10.1007/s10840-015-0039-8. Epub 2015 Aug 27 [PubMed PMID: 26310298]

Still AM, Raatikainen P, Ylitalo A, Kauma H, Ikäheimo M, Antero Kesäniemi Y, Huikuri HV. Prevalence, characteristics and natural course of inappropriate sinus tachycardia. Europace : European pacing, arrhythmias, and cardiac electrophysiology : journal of the working groups on cardiac pacing, arrhythmias, and cardiac cellular electrophysiology of the European Society of Cardiology. 2005 Mar:7(2):104-12 [PubMed PMID: 15763524]

Zadourian A, Doherty TA, Swiatkiewicz I, Taub PR. Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome: Prevalence, Pathophysiology, and Management. Drugs. 2018 Jul:78(10):983-994. doi: 10.1007/s40265-018-0931-5. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29943373]

Agarwal AK, Garg R, Ritch A, Sarkar P. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. Postgraduate medical journal. 2007 Jul:83(981):478-80 [PubMed PMID: 17621618]

Chin A, Vezi B, Namane M, Weich H, Scott-Millar R. An approach to the patient with a suspected tachycardia in the emergency department. South African medical journal = Suid-Afrikaanse tydskrif vir geneeskunde. 2016 Mar:106(3):246-50 [PubMed PMID: 27303760]

Ruzieh M, Moustafa A, Sabbagh E, Karim MM, Karim S. Challenges in Treatment of Inappropriate Sinus Tachycardia. Current cardiology reviews. 2018 Mar 14:14(1):42-44. doi: 10.2174/1573403X13666171129183826. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29189171]

Vincent JL, De Backer D. Circulatory shock. The New England journal of medicine. 2013 Oct 31:369(18):1726-34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1208943. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24171518]

Van Dam MN, Hashmi MF, Fitzgerald BM. Pulsus Paradoxus. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29493917]

Craige E. Gallop rhythm. Progress in cardiovascular diseases. 1967 Nov:10(3):246-61 [PubMed PMID: 4865414]

Grace RF. Pulse oximetry. Gold standard or false sense of security? The Medical journal of Australia. 1994 May 16:160(10):638-44 [PubMed PMID: 8177111]

Thomas JT, Kelly RF, Thomas SJ, Stamos TD, Albasha K, Parrillo JE, Calvin JE. Utility of history, physical examination, electrocardiogram, and chest radiograph for differentiating normal from decreased systolic function in patients with heart failure. The American journal of medicine. 2002 Apr 15:112(6):437-45 [PubMed PMID: 11959053]

Lee SM, An WS. New clinical criteria for septic shock: serum lactate level as new emerging vital sign. Journal of thoracic disease. 2016 Jul:8(7):1388-90. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2016.05.55. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27501243]

Sajadi-Ernazarova KR, Martin J, Gupta N. Acute Pneumothorax Evaluation and Treatment. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30855900]

Corrigan D, Prucnal C, Kabrhel C. Pulmonary embolism: the diagnosis, risk-stratification, treatment and disposition of emergency department patients. Clinical and experimental emergency medicine. 2016 Sep:3(3):117-125 [PubMed PMID: 27752629]

Reno CM, Daphna-Iken D, Chen YS, VanderWeele J, Jethi K, Fisher SJ. Severe hypoglycemia-induced lethal cardiac arrhythmias are mediated by sympathoadrenal activation. Diabetes. 2013 Oct:62(10):3570-81. doi: 10.2337/db13-0216. Epub 2013 Jul 8 [PubMed PMID: 23835337]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHoffman RS. Treatment of patients with cocaine-induced arrhythmias: bringing the bench to the bedside. British journal of clinical pharmacology. 2010 May:69(5):448-57. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03632.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20573080]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePeyrol M, Lévy S. Clinical presentation of inappropriate sinus tachycardia and differential diagnosis. Journal of interventional cardiac electrophysiology : an international journal of arrhythmias and pacing. 2016 Jun:46(1):33-41. doi: 10.1007/s10840-015-0051-z. Epub 2015 Sep 2 [PubMed PMID: 26329720]

Patti L, Ashurst JV. Supraventricular Tachycardia. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28723001]

Imrie JR, Yee R, Klein GJ, Sharma AD. Incidence and clinical significance of ST segment depression in supraventricular tachycardia. The Canadian journal of cardiology. 1990 Oct:6(8):323-6 [PubMed PMID: 2268794]

Dang D, Arimie R, Haywood LJ. A review of atrial fibrillation. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2002 Dec:94(12):1036-48 [PubMed PMID: 12510703]

Cosío FG. Atrial Flutter, Typical and Atypical: A Review. Arrhythmia & electrophysiology review. 2017 Jun:6(2):55-62. doi: 10.15420/aer.2017.5.2. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28835836]

Cossú SF, Steinberg JS. Supraventricular tachyarrhythmias involving the sinus node: clinical and electrophysiologic characteristics. Progress in cardiovascular diseases. 1998 Jul-Aug:41(1):51-63 [PubMed PMID: 9717859]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLow PA, Sandroni P, Joyner M, Shen WK. Postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS). Journal of cardiovascular electrophysiology. 2009 Mar:20(3):352-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2008.01407.x. Epub 2009 Jan 16 [PubMed PMID: 19207771]

Armen SB, Freer CV, Showalter JW, Crook T, Whitener CJ, West C, Terndrup TE, Grifasi M, DeFlitch CJ, Hollenbeak CS. Improving Outcomes in Patients With Sepsis. American journal of medical quality : the official journal of the American College of Medical Quality. 2016 Jan-Feb:31(1):56-63. doi: 10.1177/1062860614551042. Epub 2014 Sep 12 [PubMed PMID: 25216849]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLeeper B, Cyr AM, Lambert C, Martin K. Acute coronary syndrome. Critical care nursing clinics of North America. 2011 Dec:23(4):547-57. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2011.10.001. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22118113]

Gopinathannair R, Olshansky B. Management of tachycardia. F1000prime reports. 2015:7():60. doi: 10.12703/P7-60. Epub 2015 May 12 [PubMed PMID: 26097733]

Ludikhuize J, Smorenburg SM, de Rooij SE, de Jonge E. Identification of deteriorating patients on general wards; measurement of vital parameters and potential effectiveness of the Modified Early Warning Score. Journal of critical care. 2012 Aug:27(4):424.e7-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2012.01.003. Epub 2012 Feb 14 [PubMed PMID: 22341727]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencevan Galen LS, Dijkstra CC, Ludikhuize J, Kramer MH, Nanayakkara PW. A Protocolised Once a Day Modified Early Warning Score (MEWS) Measurement Is an Appropriate Screening Tool for Major Adverse Events in a General Hospital Population. PloS one. 2016:11(8):e0160811. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0160811. Epub 2016 Aug 5 [PubMed PMID: 27494719]

Kause J, Smith G, Prytherch D, Parr M, Flabouris A, Hillman K, Intensive Care Society (UK), Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society Clinical Trials Group. A comparison of antecedents to cardiac arrests, deaths and emergency intensive care admissions in Australia and New Zealand, and the United Kingdom--the ACADEMIA study. Resuscitation. 2004 Sep:62(3):275-82 [PubMed PMID: 15325446]

Ludikhuize J, Borgert M, Binnekade J, Subbe C, Dongelmans D, Goossens A. Standardized measurement of the Modified Early Warning Score results in enhanced implementation of a Rapid Response System: a quasi-experimental study. Resuscitation. 2014 May:85(5):676-82. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.02.009. Epub 2014 Feb 20 [PubMed PMID: 24561029]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCavanaugh JB Jr, Sullivan JB, East N, Nodzon JN. Importance of Pharmacy Involvement in the Treatment of Sepsis. Hospital pharmacy. 2017 Mar:52(3):191-197. doi: 10.1310/hpj5203-191. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28439133]

Cohen RI, Eichorn A, Motschwiller C, Laktikova V, La Torre G, Ginsberg N, Steinberg H. Medical intensive care unit consults occurring within 48 hours of admission: a prospective study. Journal of critical care. 2015 Apr:30(2):363-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2014.11.001. Epub 2014 Nov 6 [PubMed PMID: 25465025]

Schellings DA, Symersky T, Ottervanger JP, Ramdat Misier AR, de Boer MJ. Clinical cardiology consultation at non-cardiology departments: stepchild of patient care? Netherlands heart journal : monthly journal of the Netherlands Society of Cardiology and the Netherlands Heart Foundation. 2012 Jun:20(6):260-3. doi: 10.1007/s12471-012-0273-y. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22644999]