Introduction

Sudoriferous glands, also known as sweat glands, are either of two types of secretory skin glands, eccrine or apocrine. Eccrine and apocrine glands reside within the dermis and consist of secretory cells and a central lumen into which material is secreted. Typically, eccrine glands open directly onto the skin surface, whereas apocrine glands open onto associated hair follicles. As such, eccrine glands can be found almost anywhere on the human body, with the highest concentration found on the palms and soles. Apocrine glands are found in more restricted areas of the body, including the axilla, anogenital region, external ear canal, and areola.[1][2][3][4][3]

Eccrine glands consist of a tube-shaped duct that ends in a coiled, secretory unit. This secretory unit is made up of cuboidal cells that surround a central lumen. Myoepithelial cells form around the cuboidal cells and contract in response to stimuli to assist with secretion.

Apocrine glands have a similar structure to eccrine glands but have a larger secretory component lined by either cuboidal or columnar epithelium and associated myoepithelial cells.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

Both eccrine and apocrine glands secrete in a merocrine manner such that substances are released by exocytosis without damage or loss of the secreting cell.[5][2][6]

Eccrine sweat glands allow for temperature control. When body temperature rises during physical activity, increased ambient temperature, or fever, these glands respond by secreting sweat. This sweat is eventually evaporated from the surface of the skin, effectively cooling down body temperature. The initial sweat released by eccrine glands is made up of water as well as sodium and potassium ions; however, the epithelial lining of the ducts reabsorbs a majority of these ions, resulting in a larger water composition of sweat.

Apocrine glands present at birth do not become active until puberty. In some mammals, these glands act as the main thermoregulator; however, their function is unknown in humans. Some hypothesize that apocrine glands are responsible for body odor or pheromone production. While the initial secretion of apocrine glands is milky and odorless, bacteria on the skin surface eventually break down the fluid, releasing a distinctive odor.

Embryology

Eccrine glands are derived from embryonic ectoderm. These glands form on the palmoplantar skin around the fourth month of gestation and develop across the remainder of the body about one month later. Eccrine glands are completely formed by the time of birth.

Apocrine glands are derived from the differential of a hair follicle. Hair follicles typically begin to develop in the head of an embryo at about 9 weeks and continue to develop caudally. These follicles are made up of cells that eventually differentiate into the follicle, infundibulum, sebaceous, and apocrine units. At about 4 months of gestation, the apocrine gland arises from the infundibulum, the epithelial structure below the hair follicle, and is continuous with the skin epidermis.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

In the dermis, two vascular plexuses lie parallel to the surface of the skin. These superficial and deep plexuses lie in the superficial and deep aspects of the reticular dermis, respectively. Capillaries run perpendicular to and connect these plexuses and envelop different adnexa of the skin, including both eccrine and apocrine glands.

Lymphatics lie parallel to the skin blood supply. Close-ended lymphatic capillaries begin in the dermal papillae and drain into underlying deep dermal and subdermal plexuses. These plexuses then combine into larger lymphatic channels that eventually drain into the venous system.

Nerves

The sympathetic nervous system innervates eccrine glands. Both cholinergic and adrenergic nerve fibers can mediate sweat secretion, though cholinergic fibers are predominant. Cortical, medullary, and hypothalamic mediators in the central nervous system control these nerve fibers. Cortical sweating is secondary to emotions and leads to sweating of both the palms and soles. Medullary sweating is due to spicy foods and leads to sweating of the face. Hypothalamic sweating occurs in response to an increase in core body temperature and leads to sweating diffusely.

Apocrine glands secrete in response to both epinephrine and norepinephrine; however, it is unknown whether these neurotransmitters are released in response to sympathetic activation or if they are simply circulating throughout the body.

Clinical Significance

Hyperhidrosis is a condition in which patients sweat more than necessary to regulate core body temperature. There are two major types of hyperhidrosis: primary focal and generalized. In the primary focal form, patients have excessive sweating of the palms, soles, and axilla due to dysregulation of the autonomic nervous system. Generalized hyperhidrosis is not limited to these locations and is typically secondary to medications or systemic conditions. When treating primary focal hyperhidrosis, aluminum chloride is typically used first. Alternatively, botulinum toxin and systemic agents can be considered, though these treatments pose the risk of significant adverse effects. For patients with refractory hyperhidrosis, endoscopic thoracic sympathectomy can be considered.[7][8]

Hypohidrosis and anhidrosis are conditions of diminished and absent sweat production, respectively. When a large surface area of the body is affected, individuals are at risk of developing heat stroke.

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic condition that occurs primarily in the intertriginous skin characterized by occlusion of follicles, chronic inflammation, and progressive scarring. The pathogenesis of the condition is unknown, but plugging the follicles can lead to rupture and inflammation of the apocrine glands. HS is associated with smoking and several other conditions, including obesity, polycystic ovarian syndrome, insulin resistance, and inflammatory bowel disease. While HS initially appears as nodules, most commonly in the axilla, these nodules often rupture, releasing mucopurulent discharge. When nodules recur, sinus tracts are often formed. Treatment for HS includes preventative care as well as medical and surgical therapy. Topical and oral antibiotics are considered first-line therapy. However, systemic medications should be considered for unresponsive diseases. For patients with severe disease, surgical excision can provide permanent relief.[8]

Bromhidrosis is a condition in which an individual has excessive body odor. There are two variants depending on whether eccrine or apocrine glands are affected. Apocrine bromhidrosis occurs only after puberty and is typically due to bacteria breaking down fatty acids in sweat. The type of skin flora present influences the odor, and Corynebacterium is thought to produce a particularly pungent scent. Eccrine bromhidrosis can be either localized or generalized. Localized eccrine bromhidrosis occurs most commonly on the feet as well as other areas that are particularly prone to maceration secondary to sweat as this leads to the bacterial breakdown of keratin and the production of odor. Generalized eccrine bromhidrosis usually occurs due to ingestion of certain substances or systemic illness. Therapies for bromhidrosis are generally targeted at reducing sweat and bacteria from the affected area, though antibiotics and surgical sweat gland destruction can be considered.[9]

Chromhidrosis, or colored sweat, is due to the presence of lipofuscin pigment in sweat glands, most commonly apocrine sweat glands. This pigment can lead to the production of yellow, blue, green, or black sweat. Treatments include botulinum toxin injection and capsaicin cream.

Miliaria, or sweat rash, is a skin disease caused by the blockage or inflammation of eccrine sweat glands. There are three types of miliaria dependent on the level of obstruction: crystalline, rubra, and profunda. Treatment for miliaria includes maintaining a cool environment, cool compresses, and applying topical corticosteroids and calcineurin inhibitors.

Fox-Fordyce is a skin disorder caused by the blockage of apocrine sweat glands that leads to the formation of pruritic, skin-colored papules, most commonly in the axilla and groin. This condition can occur in any individual, but women between the ages of 13 and 35 are the most at risk. Topical therapies include corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, clindamycin, and retinoids. Other forms of treatment include surgical excision and phototherapy.[10]

Media

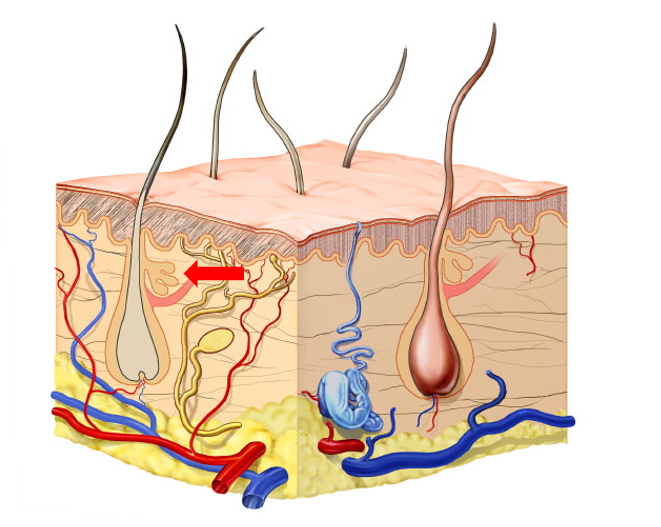

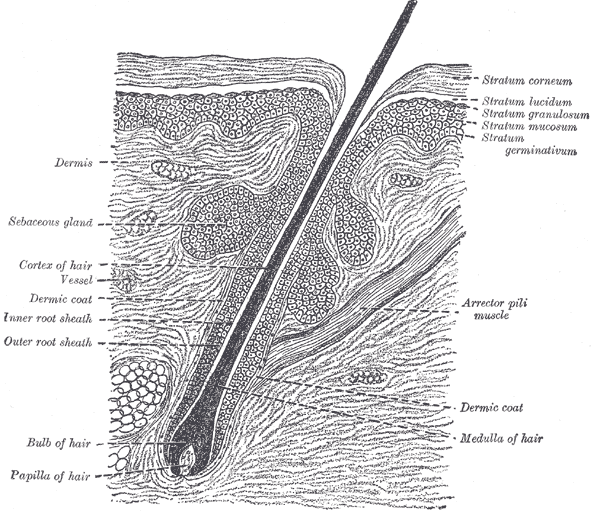

(Click Image to Enlarge)

The Common Integument, Section of the Skin. A section of the skin showing the epidermis, dermis, hair shaft and follicle, arrector pili muscles, and sebaceous glands.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Agarwal S, Krishnamurthy K. Histology, Skin. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30726010]

Gagnon D, Crandall CG. Sweating as a heat loss thermoeffector. Handbook of clinical neurology. 2018:156():211-232. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-63912-7.00013-8. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30454591]

Gerrett N, Amano T, Havenith G, Inoue Y, Kondo N. The influence of local skin temperature on the sweat glands maximum ion reabsorption rate. European journal of applied physiology. 2019 Mar:119(3):685-695. doi: 10.1007/s00421-018-04059-5. Epub 2019 Feb 7 [PubMed PMID: 30730000]

Shah A, Tsianou Z, Suchak R, Mann J. Apocrine Chromhidrosis. The American Journal of dermatopathology. 2020 Oct:42(10):e147-e148. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0000000000001712. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32568832]

Jung D, Kim YB, Lee JB, Muhamed AMC, Lee JY. Sweating distribution and active sweat glands on the scalp of young males in hot-dry and hot-humid environments. European journal of applied physiology. 2018 Dec:118(12):2655-2667. doi: 10.1007/s00421-018-3988-7. Epub 2018 Sep 12 [PubMed PMID: 30209544]

Shiohara T, Mizukawa Y, Shimoda-Komatsu Y, Aoyama Y. Sweat is a most efficient natural moisturizer providing protective immunity at points of allergen entry. Allergology international : official journal of the Japanese Society of Allergology. 2018 Oct:67(4):442-447. doi: 10.1016/j.alit.2018.07.010. Epub 2018 Sep 1 [PubMed PMID: 30181012]

Ferstl P, Wohlfart S, Schneider H. Sweating ability of patients with p63-associated syndromes. European journal of pediatrics. 2018 Nov:177(11):1727-1731. doi: 10.1007/s00431-018-3227-6. Epub 2018 Aug 7 [PubMed PMID: 30088137]

Murota H, Yamaga K, Ono E, Katayama I. Sweat in the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis. Allergology international : official journal of the Japanese Society of Allergology. 2018 Oct:67(4):455-459. doi: 10.1016/j.alit.2018.06.003. Epub 2018 Aug 3 [PubMed PMID: 30082151]

Semkova K, Gergovska M, Kazandjieva J, Tsankov N. Hyperhidrosis, bromhidrosis, and chromhidrosis: Fold (intertriginous) dermatoses. Clinics in dermatology. 2015 Jul-Aug:33(4):483-91. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2015.04.013. Epub 2015 Apr 8 [PubMed PMID: 26051066]

Hanner S, Schneiderbauer R, Enk A, Toberer F. [Axillary and perimamillary Fox-Fordyce disease (apocrine miliaria) in a 19-year-old woman]. Der Hautarzt; Zeitschrift fur Dermatologie, Venerologie, und verwandte Gebiete. 2018 Apr:69(4):313-315. doi: 10.1007/s00105-017-4076-3. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29110043]