Introduction

The spleen, a vital intra-abdominal organ, is commonly injured, often leading to life-threatening bleeding. In cases of abdominal trauma, prompt differentiation of spleen injuries is imperative for clinicians.[1] The management of splenic trauma necessitates an interprofessional healthcare team knowledgeable about the physiological and immunological changes that can occur. As the body's most vascular organ, the spleen often sustains injuries resulting in significant bleeding and hemoperitoneum. The spleen is critical for various physiological processes, such as immunological functions. Understanding the nuances of splenic injuries is crucial, as overlooking them can lead to preventable traumatic deaths.[2][3]

The spleen's unique vascular nature contributes significantly to the severity of splenic injuries, with arterial bleeding often leading to significant hemoperitoneum. Notably, bleeding from such injuries primarily occurs intraperitoneally, complicating both clinical presentation and management. Traditionally, the organ's immunological functions have guided clinical decisions regarding splenic trauma, favoring preservation over removal whenever possible. However, technological advancements, notably the widespread use of computed tomography (CT) scans, have revolutionized the approach to splenic injuries. These imaging tools enable clinicians to adopt conservative management strategies and preserve the spleen whenever possible.

In the pediatric population, where splenic injuries often require surgical interventions, clinicians must remain vigilant for signs of fatal complications. Navigating the intricacies of splenic injuries demands a comprehensive grasp of the organ's distinct vascular and immunological characteristics. The utilization of diagnostic tools and therapeutic strategies is imperative to improve patient outcomes and reduce the likelihood of preventable morbidity and mortality associated with splenic trauma.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The primary cause of splenic injury is most frequently attributed to motor vehicle accidents. Direct blunt trauma and falls are also significant contributors to spleen-related trauma cases. Additionally, penetrating trauma, such as abdominal gunshot wounds, accounts for 7% to 9% of total penetrating trauma cases. Other mechanisms of injury include indirect trauma, such as a tear in the splenic capsule during colonoscopy or excessive traction on the splenocolic ligament during surgical procedures.[4][5]

Epidemiology

In the United States, splenic injuries are relatively common occurrences resulting from trauma. Motor vehicle accidents stand out as a significant contributor to these injuries, followed closely by blunt trauma, falls, and penetrating injuries such as gunshot wounds. Implementing safety measures, improved trauma care, and advancements in diagnostic imaging technology have collectively influenced the epidemiology and outcomes of splenic injuries in the United States. On average, each year witnesses approximately 25% (800-1200) of admissions due to blunt trauma to the spleen, with blunt splenic injury accounting for 25% to 30% of pediatric abdominal trauma.[6]

Pathophysiology

Injury to the spleen can result in significant blood loss from the parenchyma and the arteries and veins that supply blood to the spleen. The spleen is an essential lymphopoietic organ, contributing significantly to immune function and maintaining homeostasis.[7]

The spleen has the following functions:

Hematological Functions

- Maturation of red cells: The spleen actively participates in the maturation process of red blood cells, ensuring optimal functionality.

- Extraction of abnormal cells: The spleen extracts and removes abnormal cells through phagocytosis—a crucial mechanism in maintaining the quality of blood cells.

Immunological Functions

- Contribution to immunity: The spleen is involved in both humoral immunity and cell-mediated immunity, actively contributing to the body's defense mechanisms.

- Particulate removal: The spleen operates as a refined filter, removing particulates, opsonized bacteria, and antibody-coated cells from the bloodstream.

The average adult spleen weighs approximately 250 g and is 13 cm long. Notably, the spleen undergoes involution with age and is typically not palpable in adults. Furthermore, its pliability diminishes in adults compared to children, highlighting the age-related variations in structural characteristics.

In patients with trauma, splenic disruption can occur with or without capsular injury. If the capsule remains intact, an intraparenchymal or subcapsular hematoma develops. However, laceration of the splenic capsule results in hemoperitoneum and a splenic hematoma.

History and Physical

The emergency clinician must evaluate for intra-abdominal injury in patients exhibiting signs of extra-abdominal injury, even if they are hemodynamically stable and have no abdominal complaints. In cases of hemodynamic instability, immediate resuscitation and assessment are crucial.

When interacting with the patient, inquire about their surgical history, including any previous splenectomy, as well as their use of anticoagulants and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications. During the physical examination, carefully assess the abdomen for external signs of trauma such as abrasions, lacerations, contusions, and seatbelt signs. However, the absence of these external findings does not rule out intra-abdominal injury, as up to 10% to 20% of patients with such injuries may not exhibit these signs during examination. Furthermore, initial examination upon arrival may not reveal tenderness, rigidity, or distention. Clinicians should be aware that the absence of abdominal pain or tenderness does not necessarily indicate the absence of significant intra-abdominal injury, and all trauma patients should be evaluated for intra-abdominal bleeding.

Based on a review of 12 studies involving almost 11,000 patients, certain physical examination findings are strongly associated with intra-abdominal injury following blunt abdominal trauma. The seatbelt sign, rebound tenderness, hypotension (systolic blood pressure of less than 90 mm Hg), abdominal distension, abdominal guarding, and concomitant femur fracture are the most significant indicators of intra-abdominal injury. Notably, observational evidence has also confirmed the association of the seatbelt sign with intra-abdominal injury. Femur fractures, in particular, are distracting injuries that suggest blunt abdominal trauma in pedestrians struck by cars.[8] While the absence of these signs and symptoms may reduce the probability of intra-abdominal injury, their nonexistence, whether alone or in combination, is insufficient to completely rule out the likelihood of injury.[9]

The presentation of splenic injury varies depending on the associated internal hemorrhage. Patients may present with hypovolemic shock, characterized by tachycardia and hypotension. Additional findings may include tenderness in the upper left quadrant, generalized peritonitis, or referred pain in the left shoulder (known as Kehr sign), which is a rare finding that should raise suspicion of splenic injury. Some patients may also experience pleuritic left-sided chest pain. However, physical examination may be limited by decreased mental status or distracting injuries.

Evaluation for splenic injury should be undertaken if lower left rib fractures, particularly below the sixth rib, are identified. In adults, up to 20% of patients with lower left rib fractures may have an associated splenic injury. However, in children, the chest wall's plasticity can lead to severe underlying spleen injury, even in the absence of rib fractures. Additionally, clinicians should consider the possibility of bowel injuries in patients presenting with blunt splenic trauma, as this occurs in less than 5% of patients initially suspected to have an isolated organ injury.

Evaluation

Several radiological adjuncts are used to detect splenic injuries, with the primary methods being the focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST) and CT scans.[1][10]

The FAST examination is a rapid diagnostic tool for detecting free intraperitoneal fluid in patients with blunt abdominal trauma. Particularly beneficial in assessing hemodynamically unstable patients, the examination involves 4 acoustic windows—pericardiac, perihepatic, perisplenic, and pelvic. A positive FAST result is indicated by the presence of fluid and is observed as an anechoic band or a black rim around the spleen. Although ultrasound is sensitive in detecting hemoperitoneum, intraperitoneal hemorrhage may not always be present, especially if the splenic capsule remains intact. The presence of localized fluid around the spleen indicates splenic laceration. However, up to 25% of splenic injuries may lack intraperitoneal hemorrhage. In cases of hemodynamic instability with free fluid on FAST examination, prompt surgical evaluation and immediate laparotomy are warranted due to the high risk of spleen loss or fatality.

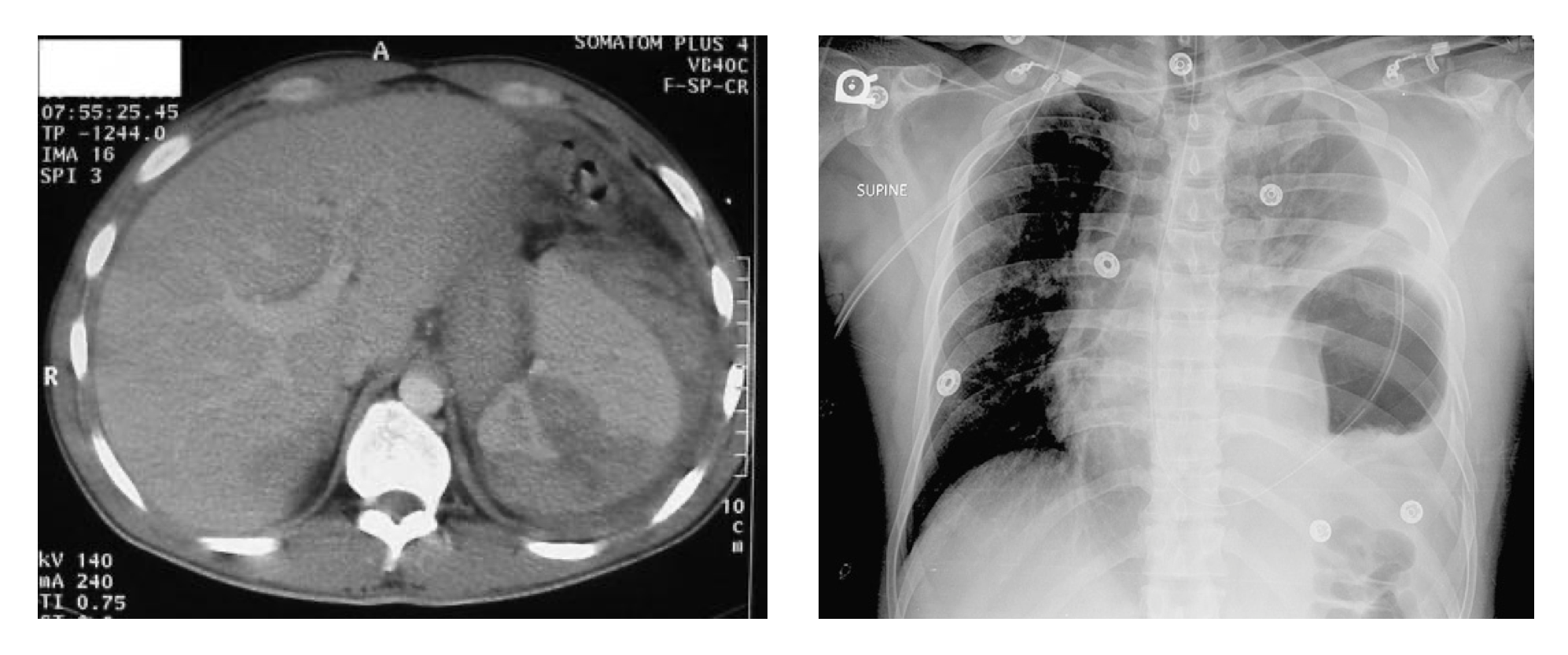

CT scans serve as the preferred diagnostic modality for detecting solid organ injuries, including those affecting the spleen. These scans can reveal disruptions in normal splenic parenchyma, surrounding hematomas, and free intra-abdominal blood. A contrast-enhanced CT scan is particularly valuable for assessing differences in splenic parenchyma and hematoma density, which aids in identifying associated injuries. High-quality imaging is crucial, as suboptimal scans may result in missed diagnoses of subtle splenic injuries. Overall, CT scans offer a rapid and accurate diagnosis, contributing significantly to improved clinical outcomes (see Image. Comparative Analysis of CT and CXR Imaging Findings in Suspected Splenic Injury).[11]

Standard laboratory tests may not be beneficial in the acute management of traumatic injuries in patients. However, when combined with other clinical findings, they can help identify patients at low risk for significant injury. In situations where intra-abdominal injury is uncertain, clinicians often obtain a microscopic urinalysis. This is because the presence of greater than 25 red blood cells per high-power field in the urinalysis raises the probability of significant intra-abdominal injury, which could include traumatic injury to the spleen.[12]

The hematocrit level serves as a critical indicator of the likelihood of intra-abdominal injury following blunt abdominal trauma, with a level below 30% suggesting an elevated risk of such injuries. In hypotensive patients presenting acutely with trauma and normal hematocrit levels, the potential for internal hemorrhage should not be dismissed. Clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for such injuries to ensure prompt and effective interventions are implemented.[13]

Similarly, the white blood cell (WBC) count is a nonspecific marker. Both elevated and normal WBC counts have limited positive or negative predictive value. Trauma-induced catecholamine release can lead to demargination, resulting in WBC counts ranging from 12,000 to 20,000/μL with a moderate left shift. Similarly, elevations in WBC counts may occur in cases of solid organ (including splenic) or hollow viscus injury.[14]

Treatment / Management

Treatment strategies for splenic injury include 3 modalities—nonoperative, operative, and embolization.

The primary goal of treating splenic injury is to maximize salvage therapy through nonoperative measures, thereby avoiding the necessity for splenectomy. Successful nonoperative management can be achieved in up to 80% of blunt splenic injuries. This approach has seen a rising trend in usage among adults, with age showing no discernible influence on outcomes in the nonoperative management of blunt splenic trauma. Injuries in which bleeding has ceased can often be managed without resorting to splenectomy, although patients may still be at risk of developing delayed hemorrhaging. Delayed splenic rupture is a potential complication that can manifest up to 10 days following an injury. The rate of late bleeding, estimated at up to 10.6%, varies depending on the grade rating of the splenic injury. Nonoperative management is suitable only for hemodynamically stable patients without signs of peritonitis. In children with high-grade injuries, nonoperative management may be attempted as long as the patient remains hemodynamically stable without evidence of active bleeding. In addition, it is crucial to hospitalize these patients in a facility equipped with pediatric surgical expertise for close observation and multiple examinations. In this scenario, surgical intervention must be readily available at all times.[15][16]

Operative intervention and splenectomy continue to be life-saving measures for numerous patients. The decision for surgical intervention hinges on the clinical or hemodynamic status as well as the findings from imaging studies. Generally, patients who do not respond to resuscitation and have intra-abdominal fluid detected on FAST examination necessitate exploration. Moreover, patients requiring transfusions of more than 2 units of blood or exhibiting signs of ongoing bleeding should be evaluated for operative management or embolization.

The common indications for splenectomy include:

- Hemodynamic instability: Hemodynamically unstable patients should be taken emergently to the operating room, which is considered an indication of emergent splenectomy.

- Peritonitis

- Pseudoaneurysm formation

- Associated intra-abdominal injuries that require surgical exploration, such as bowel injuries

Arterial embolization may be an alternative to surgery in selected hemodynamically stable patients requiring ongoing blood transfusions.[17] Splenic embolization requires specialized imaging facilities and a vascular interventionist.

Guidelines for embolization in patients with spleen trauma are listed below. For the grading system, see the Staging section.

- Grade III or higher splenic injury

- Contrast blush on CT scan

- Moderate hemoperitoneum

- Evidence of ongoing bleeding

Nonoperative management with splenic arteriography and angioembolization has been increasingly used.[18] Angiography and embolization are commonly used in treating vascular injuries affecting the liver and spleen in adults. Previously, prophylactic embolization was not recommended for stable patients who show an arterial blush on CT.[19] According to the 2022 World Society of Emergency Surgery consensus document, splenic artery embolization is currently recommended as the primary intervention in hemodynamically stable patients presenting with arterial blush on CT scans, irrespective of injury severity.[20] However, their application in the pediatric population is primarily restricted to isolated case reports and series. Limited evidence suggests that angiography may serve as a viable alternative to surgery in hemodynamically unstable children with blunt liver or spleen injury demonstrating an arterial blush on CT imaging.(A1)

Currently, universally recognized protocols for determining the necessity of surgical intervention in cases of blunt splenic trauma are lacking. One proposed criterion suggests that replacing over 50% of the estimated circulating blood volume, equivalent to approximately 40 mL/kg packed red blood cells, may indicate the need for surgical intervention. In many cases, pediatric traumas are managed in hospitals where adult trauma surgeons provide care to patients.[21] This approach has been associated with a 10-fold increased risk of splenectomy compared to pediatric trauma surgeons.[22] However, when making these decisions, one must consider the patient's overall injury severity and physiological status. The threshold for considering splenectomy should be reduced in patients with multiple traumas or those experiencing physiological instability, including coagulopathy. Decisions regarding disposition should be guided by the patient's clinical condition rather than solely by the grade of injury.[23]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of splenic injuries includes liver laceration, retroperitoneal bleeding, diaphragmatic injury, and pancreas injury.

Staging

The American Association of Surgery and Trauma (AAST) has established 5 grades of spleen injury, including imaging, operative, and pathological criteria for each grade.

- Grade I injuries are characterized by subcapsular hematomas less than 10% of the surface area, parenchymal lacerations measuring less than 1 cm in depth, and capsular tears.

- Grade II injuries involve subcapsular hematomas covering 10% to 50% of the surface area, intraparenchymal hematomas less than 5 cm long, and parenchymal lacerations measuring 1 to 3 cm long.

- Grade III injuries include subcapsular hematomas greater than 50% of the surface area or expanding hematomas, ruptured subcapsular or intraparenchymal hematomas greater than or equal to 5 cm in depth, and parenchymal lacerations greater than 3 cm in depth.

- Grade IV injuries include any injuries occurring alongside a splenic vascular injury or active bleeding confined within the splenic capsule. In addition, a parenchymal laceration involving segmental or hilar vessels resulting in more than 25% devascularization is classified as a grade IV injury.

- Grade V injuries are characterized by any splenic vascular injury with active bleeding extending beyond the spleen into the peritoneum, a shattered spleen, and hilar vascular injury resulting in devascularization of the spleen.[24]

The classification used to discern splenic injuries typically relies on CT imaging. However, when it comes to liver and spleen injuries, surgical intervention is based on the patient's hemodynamic status rather than solely on CT results.[16]

Prognosis

In general, the physiological stability of the patient is a significant predictor of successful nonoperative management. The CT-based grading system effectively evaluates patients with blunt splenic injury. Overall, patients with low-grade splenic injury managed conservatively typically experience favorable outcomes. However, individuals undergoing splenectomy remain vulnerable to infections. Mitigating these risks involves administering appropriate post-splenectomy vaccines. Furthermore, associated injuries, such as traumatic brain injury combined with splenic injury treated with splenectomy, exhibit a higher in-hospital mortality compared to patients without splenectomy.[25]

Complications

Complications after splenic injuries include:

- Delayed splenic rupture, though rare, may manifest up to 10 days post-injury, often associated with subtle low-grade spleen injuries that may not have been detected in imaging studies.

- Readmission due to bleeding

- Splenic artery pseudoaneurysm

- Post-splenectomy infection risk is highest within the first 2 years after splenectomy, but it can occur at any time

- Splenic abscess

- Pancreatitis

- Death

Common complications of embolization include:

- Splenic infarction is the devascularization of more than 25% of the spleen, which may occur in up to 20% of patients after embolization.

- Re-hemorrhage

- Abscess formation

The loss of splenic tissue diminishes immune activity, leading to impaired responses to bacteremia. The effects of splenectomy include:

- Poor response to immunization with particulate antigens

- Decreased levels of phagocytosis

- Deficiency of serum immunoglobulin M (IgM) level

- Decreased properdin level

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Post-splenectomy patients should receive vaccinations against encapsulated bacteria before hospital discharge. These vaccines include pneumococcal, Haemophilus influenza type B, and meningococcal series by day 14 or upon discharge.[26] Follow-up vaccinations for meningococcal are needed at 2-month intervals. Prophylactic antibiotics are also recommended. Children should receive penicillin V (250 mg/d) for at least 2 years, with life-long antibiotic therapy recommended for high-risk patients.

Consultations

Patients are recommended to seek consultation with a trauma or surgical specialist.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Delayed spleen rupture can occur following minor trauma; patients should be informed of when to return, such as if experiencing left-sided abdominal pain. Spleen removal predisposes individuals to infection and is linked with a lifelong risk of sepsis. This risk arises from encapsulated organisms like Streptococcus pneumoniae, Neisseria meningitidis, and Hemophilus influenzae type B, with less common involvement of gram-negative organisms such as Escherichia coli, Salmonella, and Pseudomonas. To prevent post-splenectomy infection, it is important to administer prophylactic antibiotics, provide immunization against encapsulated bacteria, and offer patient education. Yearly influenza immunization is also recommended.

Families should be informed to promptly seek medical care for febrile illnesses in patients who have undergone splenectomy, as fever is a medical emergency requiring immediate evaluation. Additionally, patients should receive education about travel-related diseases, such as malaria and babesiosis, and infections associated with dog bites, such as Capnocytophaga canimorsus. In addition, it is advisable to provide laminated information cards and medical alert bracelets to patients with asplenia.

Pearls and Other Issues

Some important things to keep in mind while treating splenic injuries include:

- The spleen is commonly injured in abdominal trauma, often leading to life-threatening hemorrhage.

- A negative FAST examination does not rule out significant intraperitoneal injury.

- A significantly increased risk of infection and overwhelming sepsis is expected after splenectomy.

- Splenectomy should be avoided. The primary objective is to salvage the spleen, and every possible effort should be made to preserve splenic tissue to mitigate the risk of infection.

- Delayed rupture of the spleen can occur up to 10 days after trauma.

- Patients with splenic injury may have associated left lower rib fractures.

- Hemodynamically stable patients can undergo conservative treatment with close monitoring in consultation with a pediatric surgical team.

- Indications for operative or angiographic intervention include active bleeding, large nonperfused portions of the spleen, and pseudoaneurysm formation.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Splenic trauma management necessitates an interprofessional healthcare team comprising physicians, nurses, radiologists, intensivists, and laboratory personnel, all of whom must be cognizant of the physiological and immunological changes accompanying such trauma. Clinicians should remain vigilant for potential physiological and immunological derangements following splenic trauma. Although conservative management through observation is now prevalent, close monitoring remains crucial. During the observation period, intensive care unit (ICU) clinicians vigilantly monitor for any worsening complications. Serial abdominal examinations and complete blood count are essential for tracking patients' progress, and any signs of hemodynamic instability must be promptly reported to the surgical team.

Following splenectomy, pharmacists should verify the appropriate vaccines and dosages and coordinate post-hospitalization vaccination plans. In the outpatient setting, a primary care physician or pediatrician is responsible for confirming and overseeing these vaccinations. Patients who undergo splenectomy are advised to wear a medical alert bracelet to alert emergency services of their medical history.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Coccolini F, Montori G, Catena F, Kluger Y, Biffl W, Moore EE, Reva V, Bing C, Bala M, Fugazzola P, Bahouth H, Marzi I, Velmahos G, Ivatury R, Soreide K, Horer T, Ten Broek R, Pereira BM, Fraga GP, Inaba K, Kashuk J, Parry N, Masiakos PT, Mylonas KS, Kirkpatrick A, Abu-Zidan F, Gomes CA, Benatti SV, Naidoo N, Salvetti F, Maccatrozzo S, Agnoletti V, Gamberini E, Solaini L, Costanzo A, Celotti A, Tomasoni M, Khokha V, Arvieux C, Napolitano L, Handolin L, Pisano M, Magnone S, Spain DA, de Moya M, Davis KA, De Angelis N, Leppaniemi A, Ferrada P, Latifi R, Navarro DC, Otomo Y, Coimbra R, Maier RV, Moore F, Rizoli S, Sakakushev B, Galante JM, Chiara O, Cimbanassi S, Mefire AC, Weber D, Ceresoli M, Peitzman AB, Wehlie L, Sartelli M, Di Saverio S, Ansaloni L. Splenic trauma: WSES classification and guidelines for adult and pediatric patients. World journal of emergency surgery : WJES. 2017:12():40. doi: 10.1186/s13017-017-0151-4. Epub 2017 Aug 18 [PubMed PMID: 28828034]

Dickinson CM, Vidri RJ, Smith AD, Wills HE, Luks FI. Can time to healing in pediatric blunt splenic injury be predicted? Pediatric surgery international. 2018 Nov:34(11):1195-1200. doi: 10.1007/s00383-018-4341-2. Epub 2018 Sep 7 [PubMed PMID: 30194477]

Boyle TA, Rao KA, Horkan DB, Bandeian ML, Sola JE, Karcutskie CA, Allen C, Perez EA, Lineen EB, Hogan AR, Neville HL. Analysis of water sports injuries admitted to a pediatric trauma center: a 13 year experience. Pediatric surgery international. 2018 Nov:34(11):1189-1193. doi: 10.1007/s00383-018-4336-z. Epub 2018 Aug 13 [PubMed PMID: 30105495]

Zarzaur BL, Rozycki GS. An update on nonoperative management of the spleen in adults. Trauma surgery & acute care open. 2017:2(1):e000075. doi: 10.1136/tsaco-2017-000075. Epub 2017 Jun 9 [PubMed PMID: 29766085]

Yang K, Li Y, Wang C, Xiang B, Chen S, Ji Y. Clinical features and outcomes of blunt splenic injury in children: A retrospective study in a single institution in China. Medicine. 2017 Dec:96(51):e9419. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000009419. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29390566]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLynch T, Kilgar J, Al Shibli A. Pediatric Abdominal Trauma. Current pediatric reviews. 2018:14(1):59-63. doi: 10.2174/1573396313666170815100547. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28814248]

Echavarria Medina A, Morales Uribe CH, Echavarria R LG, Vélez Marín VM, Martínez Montoya JA, Aguillón DF. [Associated factors to non-operative management failure of hepatic and splenic lesions secondary to blunt abdominal trauma in children]. Revista chilena de pediatria. 2017:88(4):470-477. doi: 10.4067/S0370-41062017000400005. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28898314]

Nishijima DK, Simel DL, Wisner DH, Holmes JF. Does this adult patient have a blunt intra-abdominal injury? JAMA. 2012 Apr 11:307(14):1517-27. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.422. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22496266]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJiang O, Asha SE, Keady J, Curtis K. Position of the abdominal seat belt sign and its predictive utility for abdominal trauma. Emergency medicine Australasia : EMA. 2019 Feb:31(1):112-116. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.13187. Epub 2018 Oct 16 [PubMed PMID: 30328277]

Zarzaur BL, Dunn JA, Leininger B, Lauerman M, Shanmuganathan K, Kaups K, Zamary K, Hartwell JL, Bhakta A, Myers J, Gordy S, Todd SR, Claridge JA, Teicher E, Sperry J, Privette A, Allawi A, Burlew CC, Maung AA, Davis KA, Cogbill T, Bonne S, Livingston DH, Coimbra R, Kozar RA. Natural history of splenic vascular abnormalities after blunt injury: A Western Trauma Association multicenter trial. The journal of trauma and acute care surgery. 2017 Dec:83(6):999-1005. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001597. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28570347]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceArenaza Choperena G, Cuetos Fernández J, Gómez Usabiaga V, Ugarte Nuño A, Rodriguez Calvete P, Collado Jiménez J. Abdominal trauma. Radiologia. 2023 Mar:65 Suppl 1():S32-S41. doi: 10.1016/j.rxeng.2022.09.011. Epub [PubMed PMID: 37024229]

Avellino GJ, Bose S, Wang DS. Diagnosis and Management of Hematuria. The Surgical clinics of North America. 2016 Jun:96(3):503-15. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2016.02.007. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27261791]

Sharma G, Chatterjee N, Kaushik A, Saxena S. Clinicoradiological Predictors of Severity of Traumatic Intra-Abdominal Injury in Pediatric Patients: A Retrospective Study. Cureus. 2021 Sep:13(9):e17936. doi: 10.7759/cureus.17936. Epub 2021 Sep 13 [PubMed PMID: 34660126]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSchnüriger B, Inaba K, Barmparas G, Eberle BM, Lustenberger T, Lam L, Talving P, Demetriades D. Serial white blood cell counts in trauma: do they predict a hollow viscus injury? The Journal of trauma. 2010 Aug:69(2):302-7. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181bdcfaf. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20118815]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKohler JE, Chokshi NK. Management of Abdominal Solid Organ Injury After Blunt Trauma. Pediatric annals. 2016 Jul 1:45(7):e241-6. doi: 10.3928/00904481-20160518-01. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27403671]

Notrica DM, Eubanks JW 3rd, Tuggle DW, Maxson RT, Letton RW, Garcia NM, Alder AC, Lawson KA, St Peter SD, Megison S, Garcia-Filion P. Nonoperative management of blunt liver and spleen injury in children: Evaluation of the ATOMAC guideline using GRADE. The journal of trauma and acute care surgery. 2015 Oct:79(4):683-93. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000808. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26402546]

Wesson DE. Pediatric trauma centers: coming of age. Texas Heart Institute journal. 2012:39(6):871-3 [PubMed PMID: 23304041]

Harfouche MN, Dhillon NK, Feliciano DV. Update on Nonoperative Management of the Injured Spleen. The American surgeon. 2022 Nov:88(11):2649-2655. doi: 10.1177/00031348221114025. Epub 2022 Jul 11 [PubMed PMID: 35816431]

Gates RL, Price M, Cameron DB, Somme S, Ricca R, Oyetunji TA, Guner YS, Gosain A, Baird R, Lal DR, Jancelewicz T, Shelton J, Diefenbach KA, Grabowski J, Kawaguchi A, Dasgupta R, Downard C, Goldin A, Petty JK, Stylianos S, Williams R. Non-operative management of solid organ injuries in children: An American Pediatric Surgical Association Outcomes and Evidence Based Practice Committee systematic review. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2019 Aug:54(8):1519-1526. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2019.01.012. Epub 2019 Jan 31 [PubMed PMID: 30773395]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencePodda M, De Simone B, Ceresoli M, Virdis F, Favi F, Wiik Larsen J, Coccolini F, Sartelli M, Pararas N, Beka SG, Bonavina L, Bova R, Pisanu A, Abu-Zidan F, Balogh Z, Chiara O, Wani I, Stahel P, Di Saverio S, Scalea T, Soreide K, Sakakushev B, Amico F, Martino C, Hecker A, de'Angelis N, Chirica M, Galante J, Kirkpatrick A, Pikoulis E, Kluger Y, Bensard D, Ansaloni L, Fraga G, Civil I, Tebala GD, Di Carlo I, Cui Y, Coimbra R, Agnoletti V, Sall I, Tan E, Picetti E, Litvin A, Damaskos D, Inaba K, Leung J, Maier R, Biffl W, Leppaniemi A, Moore E, Gurusamy K, Catena F. Follow-up strategies for patients with splenic trauma managed non-operatively: the 2022 World Society of Emergency Surgery consensus document. World journal of emergency surgery : WJES. 2022 Oct 12:17(1):52. doi: 10.1186/s13017-022-00457-5. Epub 2022 Oct 12 [PubMed PMID: 36224617]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLiu S, Bowman SM, Smith TC, Sharar SR. Trends in pediatric spleen management: Do hospital type and ownership still matter? The journal of trauma and acute care surgery. 2015 May:78(5):935-42. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000621. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25909412]

Lippert SJ, Hartin CW Jr, Ozgediz DE, Glick PL, Caty MG, Flynn WJ, Bass KD. Splenic conservation: variation between pediatric and adult trauma centers. The Journal of surgical research. 2013 Jun 1:182(1):17-20. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2012.07.036. Epub 2012 Jul 28 [PubMed PMID: 22939554]

Williams RF, Grewal H, Jamshidi R, Naik-Mathuria B, Price M, Russell RT, Vogel A, Notrica DM, Stylianos S, Petty J. Updated APSA Guidelines for the Management of Blunt Liver and Spleen Injuries. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2023 Aug:58(8):1411-1418. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2023.03.012. Epub 2023 Mar 23 [PubMed PMID: 37117078]

Goedecke M, Kühn F, Stratos I, Vasan R, Pertschy A, Klar E. No need for surgery? Patterns and outcomes of blunt abdominal trauma. Innovative surgical sciences. 2019 Sep:4(3):100-107. doi: 10.1515/iss-2018-0004. Epub 2019 Oct 14 [PubMed PMID: 31709301]

Mader MM, Lefering R, Westphal M, Maegele M, Czorlich P. Traumatic brain injury with concomitant injury to the spleen: characteristics and mortality of a high-risk trauma cohort from the TraumaRegister DGU®. European journal of trauma and emergency surgery : official publication of the European Trauma Society. 2022 Dec:48(6):4451-4459. doi: 10.1007/s00068-020-01544-5. Epub 2020 Nov 18 [PubMed PMID: 33206232]

Camejo L, Nandeesha N, Phan K, Chharath K, Tran T, Ciesla D, Velanovich V. Infectious outcomes after splenectomy for trauma, splenectomy for disease and splenectomy with distal pancreatectomy. Langenbeck's archives of surgery. 2022 Jun:407(4):1685-1691. doi: 10.1007/s00423-022-02446-3. Epub 2022 Jan 24 [PubMed PMID: 35075620]