Introduction

The somatosensory nervous system maintains the sensation within the various dermatomes of sensation throughout the body. The somatosensory pathway is the conduit between the different sensory modalities within the body, sending information from the periphery to the postcentral gyrus and associated cortices to convey information from the surrounding environment. Peripheral mechanoreceptors, chemoreceptors, thermoreceptors, and nociceptors transmit information via specific nerve fibers that enter the central nervous system tracts towards the brain. Each carrying a unique modality of sensation, these senses are ultimately processed and integrated into the central nervous system to help individuals interact with their environmental stimuli. The ultimate destination of these sensory stimuli is the somatosensory cortex.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

Structure of the Somatosensory Cortex

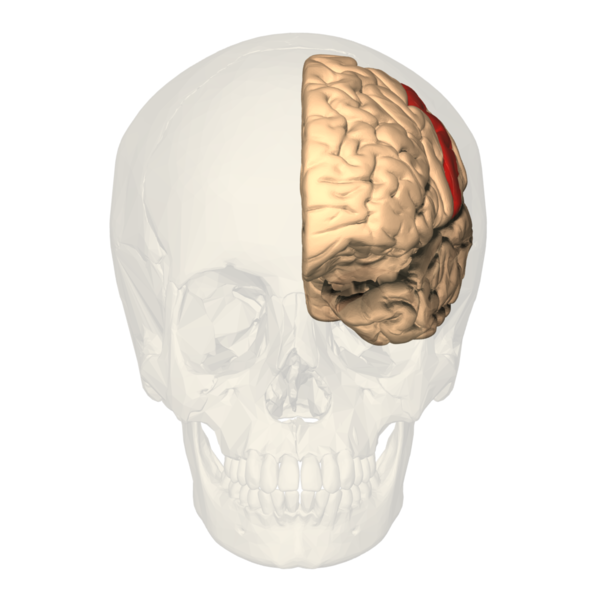

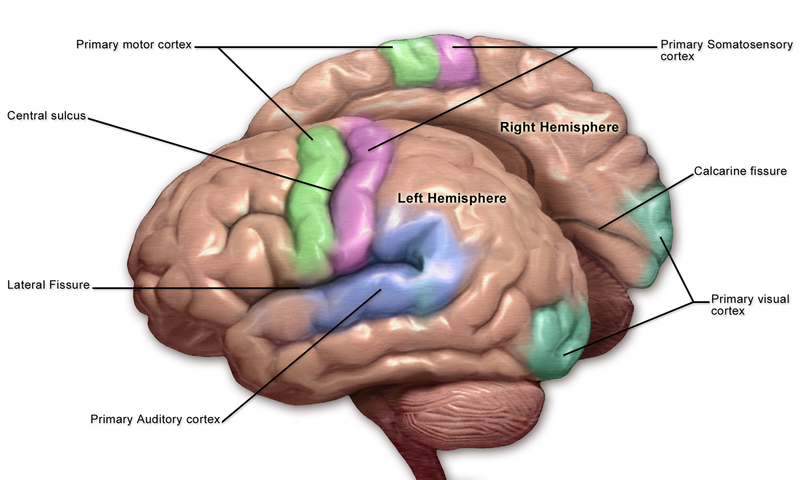

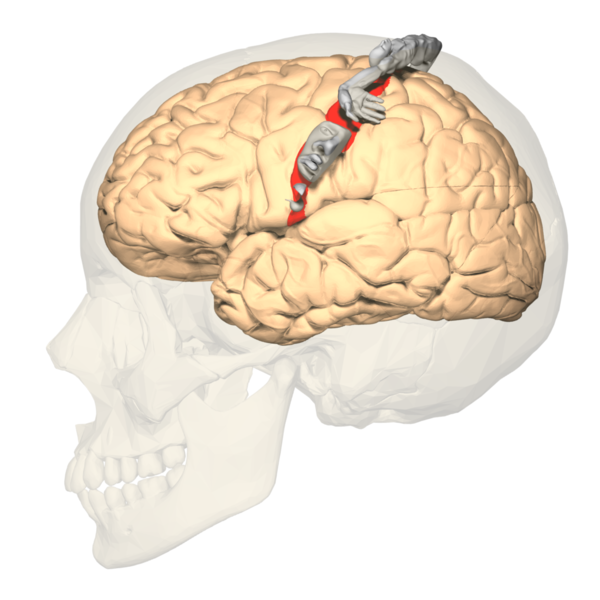

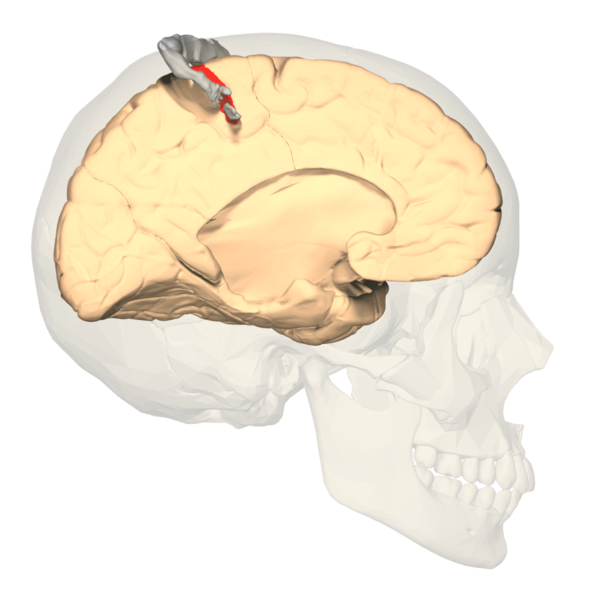

The primary somatosensory cortex (S1) and the secondary somatosensory cortex (S2) are in the parietal lobe of the brain (see Images. Primary Somatosensory Cortex Lateral View, Cortical Homunculus and Cortical Homunculus, Primary Somatosensory Cortex).

The primary somatosensory cortex is found just behind the central sulcus. It receives sensory information from the ventral posterolateral nucleus (VPL) of the thalamus via the internal capsule and corona radiata. Often referred to as the postcentral gyrus, this area receives sensory input from specific body areas, correlating to specific regions of the contralateral postcentral gyrus. This is known as somatotopy and is used to construct maps such as the sensory homunculus, as described in further detail below. Much like the rest of the neocortex, each primary cortex is paired with association cortices to help interpret and assess the initial sensory information delivered. A larger association cortex is needed to assess more complex input.

The S2 region helps to process the sensory information delivered to S1. Like the rest of the neocortex, the somatosensory cortex is organized into 6 layers. The sensory and motor layers tend to be more heterogeneous and differ in the sizes of layer 4 (internal granular) and layer 5 (internal pyramidal). Layer 4 is associated with more input, and layer 5 is associated with more output. Thus, the primary somatosensory cortex receiving peripheral input tends to have a larger 4th layer and a smaller 5th layer.

The opposite is true for the motor cortex. The association cortices tend to have a more homogenous organization in that all 6 layers are roughly the same size. While the somatosensory cortex is organized in the layers of similar cells described above, one should also note that the areas involved in similar functions are organized vertically in columns.[1][2][3]

Functional Neuroanatomy

The primary somatosensory cortex receives the peripheral sensory information but requires the secondary somatosensory cortex to store, process, and retain it (see Image. Primary Somatosensory Cortex). The S2 region has links to the hippocampus and amygdala; this helps us receive information from our environments and make decisions on how to approach them by integrating our prior stored experience, factoring our current appraisal of the stimulus, and finally forming a reaction using other areas of the brain based on the former 2 aspects to aid higher-order processing and problem-solving. The S1 region would be associated with identifying the aspects of touch, such as shape, size, and texture. The S2 region would be associated with spatial and tactile memory associated with sensory experiences.

Sensory Homunculus

The concept of somatotopy refers to the mapping points of the cortex that correspond to its function in the body. In the postcentral gyrus, the sensory homunculus is a common way of representing which portion of the coronal cut of the postcentral gyrus corresponds with the sensation in the respective part of the body. Often depicted in a coronal section of the postcentral gyrus, the medial portions of the homunculus tend to represent the hips and below, along with the genitals. In contrast, the more lateral sides of the coronal section constitute a larger area for the fingers, face, lips, eyes, and everything else that would require more sensory acuity. The sensory homunculus represents the concept by which we can use sensory deficits in the neurological physical exam to localize lesions in the sensory cortex.[4][5]

Embryology

The central nervous system comes from the neurectoderm, giving rise to the neural tube and crest. The neural tube begins to form anatomical structures induced by various transcription factors such as Sonic the Hedgehog, allowing proper migration, orientation, and patterning of cells. The rostral anterior and caudal posterior neuropores close when the neural tube forms. Problems with these neural tube closures result in neural tube defects with elevated levels of alpha-fetoprotein in prenatal testing. Following closure, the primary vesicles form. The primary vesicles include the prosencephalon, mesencephalon, and rhombencephalon. The primary vesicles then give rise to the secondary vesicles, including the telencephalon, diencephalon, mesencephalon, metencephalon, and myelencephalon. The cerebral hemispheres, including the somatosensory cortex, arise from the telencephalon. The telencephalon is a secondary vesicle that comes from the prosencephalon.[2][6][7][2]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Arterial Blood Supply

The blood supply of the somatosensory cortex arises primarily from the anterior cerebral artery (ACA) and the middle cerebral artery (MCA). The anterior cerebral artery and the middle cerebral artery arise from the bifurcation of the internal carotid artery. The anterior cerebral artery supplies most of the medial part of the frontal lobe between the hemispheres. The middle cerebral artery supplies the largest portion of the brain compared to the other cerebral arteries and supplies the lateral sides of the cerebral hemispheres. The anterior cerebral artery supplies the superomedial part of the primary sensory cortex.

In contrast, the inferolateral part receives supply from the middle cerebral artery because the ACA moves upward between the hemispheres while the MCA courses between the temporal and frontal lobes. An area between the ACA and MCA on either side of the midline is known as the watershed region and tends to experience infarction during global cerebral ischemia. The ACA and the MCA supplying the somatosensory cortex arise from the circle of Willis, which involves both the ACAs, internal carotid arteries, posterior cerebral arteries, posterior communicating arteries, and the anterior communicating artery.[8]

Venous Blood Supply

The somatosensory cortex's venous drainage enters the sinus system within the dura. The adjacent arachnoid mater contains granulations that are outlets for cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) from the subarachnoid space. Cerebral and anastomosing veins drain deoxygenated blood, waste, and metabolites into the superior sagittal sinus, which drains towards the confluence of sinuses towards the occipital pole. From there, the blood moves down the transverse sinus, sigmoid sinus, and then leaves the cranial vault via the internal jugular vein through the jugular foramen. Eventually, the internal jugular carries the blood back to the superior vena cava and back to the right heart via the subclavian and brachiocephalic veins.

Lymphatics

Despite previous suggestions that the brain did not contain the lymphatic flow, a recent paradigm shift used MRI to suggest that the lymphatic vessels exist within the dura mater. The lymphatic circulation drains the subarachnoid space CSF and interstitial fluid within the brain using aquaporins.[9]

Nerves

Receptors Sending Information to the Somatosensory Cortex

The somatosensory nervous system begins with input from peripheral receptors that eventually translate into meaningful representations in the brain. At the receptor level, various stimuli cause the sensory receptors to release receptor potentials that meet a sufficient threshold to travel to the central nervous system as action potentials. At the level of the specialized sensory receptor, the amplitude of the stimulus recognized by a receptor must reach a threshold before being communicated to the central nervous system (CNS) via interneurons and spinal tracts. The increase in amplitude is due to sodium channels that open in response to the specific stimulus. These specialized receptors communicate specific modalities of sensation, such as touch, pain, vibration, temperature, and proprioception.

When communicated beyond the level of the receptor, the action potential carries the signal via specific bundles of nerves carrying the same modality to the spinal cord within interneurons. When a sensory receptor receives a strong impulse, this translates to a higher amplitude at the level of the receptor potential. Subsequently, a higher frequency of action potentials via the nerves receiving information from these receptors given that threshold was attained.

Another principle of sensory neuroscience to consider includes the phenomena of adaptation. Different receptor types experience different degrees of adaptation and extinction. Quickly-adapting receptors (phasic) tend to adjust more quickly and send signals more frequently with changes in intensity, such as during the onset and offset of the stimulus. Phasic receptors are more important in vestibular senses, which tend to respond to changes in our body position for balance. In contrast, slowly-adapting (tonic) receptors tend to experience slower adaptation, allowing continued signaling of an active stimulus of unwavering intensity. An important example of this would be the sensation of proprioception, which requires the body to maintain information about its current position in space.[10][11][12]

Pathway to the Somatosensory Cortex

The sensation throughout the skin's surface is arranged in discrete segments that correlate to spinal cord levels. These segments are referred to as dermatomes. There is often an overlap of sensation between dermatomes, but certain points on the body may not exhibit these overlaps. By identifying the points specific to dermatomes, physicians can use these points in a neurological physical exam to identify the location of a spinal cord lesion or nerve root compression. The 1st-order neuron cell body is in the dorsal root ganglion. Each pathway to the somatosensory cortex follows a 3-ordered neuronal series from the sensory receptor in the periphery to the brain's primary somatosensory cortex.

The dorsal root ganglion fibers enter the dorsal column of the spinal cord via the dorsal nerve roots and continue upward within the spinal cord white matter of the dorsal column. The fasciculus cuneatus is more lateral and carries information from T6 and above, and the fasciculus gracilis carries information from below T6. Together, they travel up the dorsal tract and reach the nucleus cuneatus and gracilis. At the level of the lower medulla, they cross the midline and continue along the medial lemniscus to the VPL of the thalamus, the 3rd-order neuron in the pathway. The fibers move through the internal capsule from the thalamus to reach the primary somatosensory cortex. This tract is thus called the dorsal column medial lemniscus pathway (DCML) and carries information to the primary sensory cortex from the contralateral side of the body. The A-beta nerve fibers tend to carry the modalities of touch and pressure to the central nervous system and are myelinated fibers.

The sensory ascending tract would be the anterolateral spinothalamic tract (STT). This tract originates from receptors within the same dermatomal distribution, but the secondary neuron differs. In the spinothalamic tract, which carries information about pain, temperature, and crude touch, the secondary neuron is the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. The fibers from this neuron cross the anterior white commissure of the spinal cord and proceed anterolaterally to the VPL of the thalamus, finally terminating in the primary somatosensory cortex as well. Pain impulses t in specific fibers. These include A-delta pain fibers and C fibers. A-delta pain fibers tend to carry fast pain as they are myelinated, while C fibers tend to carry slow pain and are unmyelinated.[13][14]

Muscles

The proprioception receptors exist within the skeletal muscles and tendons and assist in understanding the locations of the body in space. Proprioception helps to assist our balance, movement, and coordination and is particularly important in maintaining balance without visual cues. Without proprioception, one may find difficulty walking in dimly lit or dark environments, as they have trouble understanding where their limbs are when walking. The sensory receptors involved in proprioception include the muscle spindle and the Golgi tendon organ. The muscle spindle is in parallel with muscle fibers. It contains a fusiform capsule in the center of the muscle and is innervated by gamma (A-gamma) motor neurons, which help communicate changes in the length of the muscle fibers during movement and in different positions. This information is communicated by type Ia and type II sensory fibers. The Golgi tendon organ is innervated by type Ib afferent neurons and is found in the tendons, continuously signaling muscle tension status. Together, these components help create a sense of the human body in space (proprioception) and participate in reflex arcs.[2][15][2][16]

Physiologic Variants

The somatotopic arrangement of the sensory cortex and much of the other parts of the brain are subject to the concept of plasticity. The brain adapts to the sensory needs of the body and changes in shape based on usage. Thus the cortical area that corresponds to the sensation of different body parts depends on the amount of sensory input that area of the body receives relative to other areas. Even though the amount of cortical space dedicated to sensation can change, the overall distribution of the homunculus is conserved.

Surgical Considerations

There are concerns associated with neurosurgery that must merit careful consideration to determine whether the risks of performing invasive surgery is beneficial to a patient's prognosis. In the worst cases, a neurological decline can follow the postoperative period of neurosurgery. Common complications associated with surgery include:

- Intracranial bleeds

- Brain edema

- CSF leakage

- Infection

- Ischemia

- Hyperperfusion syndrome

- Embolism and stroke

- Cranial nerve palsy, particularly after the endarterectomy of the carotid

The sensory cortex can be affected by many of the aspects contributing to potential neurological decline after surgery. Any obstruction of the anterior cerebral artery (ACA) or middle cerebral artery (MCA) causes associated sensory deficits and other neurological deficits, as this arterial system supplies more than the sensory cortex. The surgery on the vasculature itself, including the circle of Willis, can cause embolization. Thromboemboli and atheroemboli (which can arise after carotid endarterectomy) from surgical procedures can reach the ACA or MCA and result in the associated neurological symptoms. The obstruction of the ACA typically can cause sensory and motor deficits in the legs. In contrast, common manifestations of MCA obstruction include sensory and motor deficits in the face and arms (see Image. Motor and Sensory Regions of the Cerebral Cortex). Both of these obstructions are typically present unilaterally. Essentially, surgically manipulating the vasculature supplying the sensory cortex and the vessels upstream can result in embolic infarcts. Further surgical considerations include hypotension from blood loss and internal carotid obstruction, resulting in global cerebral ischemia and watershed infarcts in the area between the ACA and MCA.[17][18]

Clinical Significance

The neurological physical exam evaluates light touch, pinprick, vibration using tuning forks, and proprioceptive senses in the extremities. This examination helps the physician create a differential diagnosis for any problems in the sensation while eventually narrowing down the site of the neurological lesion. The Romberg sign is a useful physical exam finding that delineates ataxia due to cerebellar and proprioceptive problems. Proprioception is important for maintaining balance; however, it may not present as poor balance when compensated by visual stimuli. Thus, a positive Romberg sign indicating sensory proprioceptive deficit is elicited by asking the patient to stand erect with their feet together and assessing for imbalance or sway. The patient should then close their eyes for a full minute, and the examiner should evaluate for imbalance or sway. When the patient shows sway only when their eyes are closed, this is a positive sign. The initial assessment offered by a neurological physical exam gives a standardized way to appraise the sensory and neurological complaints before proceeding further.

Clinical signs and symptoms related to the sensory cortex often present with strokes. The incidence of stroke is higher in Western societies due to an increasingly sedentary lifestyle and atherogenic diets. Based on the distribution of symptoms described earlier, sensory deficits in various body parts can help determine sites of potential obstruction due to loss of blood supply to their respective parts of the somatosensory cortex. For example, the ACA supplies the superomedial part of the somatosensory cortex. Since this area receives sensory input from the lower extremities, loss of sensation in the lower extremities can help localize the source of the stroke to the ACA. The ACA and MCA supply the motor supply of the precentral gyrus and follow a similar distribution, causing an additional motor weakness in the corresponding areas as well. Since the mechanosensory modality carried in the dorsal column medial lemniscus pathway crosses the midline, the lesions produce a contralateral loss of sensation.

Watershed infarcts mentioned earlier tend to present with the FAST mnemonic, which stands for facial weakness, arm weakness, speech difficulty, and time to act. When a stroke does not receive a timely intervention, symptoms can lead to numbness and hyperreflexia in the affected area. Watershed strokes affect more than ACA or MCA strokes. They can present with additional deficits of bilateral vision loss or even proximal limb weakness that does not affect the face, hands, or feet. Watershed infarcts can be caused by congestive heart failure, atherosclerosis, thrombi, or carotid artery stenosis, to name a few.

Direct lesions of the parietal lobe can also result in a wide variety of somatosensory defects. Integrative sensorimotor functions can be affected and lead to presentations based on the severity of the lesion. Tactile apraxia is an example of a loss of integrative sensorimotor function from parietal defects involving the somatosensory cortex. Tactile apraxia is a defect in active touch feedback when manipulating objects with our hands that integrate the sensory aspect of digital palpation and spatial features of objects with the brain's motor aspect to manipulate them. It is important to note that movements of the hand, without the use of an object, are intact. Motor function without tactile feedback is intact. Lesions that affect the primary somatosensory cortex can result in a loss in the ability to discriminate objects using the touch modality only, such as shape, size, or texture. Lesions that affect the secondary somatosensory cortex affect the recognition of objects based on tactile appraisal over sensory discrimination. An individual with such a lesion has trouble recognizing an object unilaterally based on touch, known as tactile apraxia and astereognosis bilaterally. It is important to understand that the somatosensory nervous system interconnects with other areas of the brain that require intact sensory input to interact with surrounding stimuli.[3][18][19][3][20][21]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Primary Somatosensory Cortex Lateral View, Cortical Homunculus

Database Center for Life Science, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Cortical Homunculus, Primary Somatosensory Cortex

Database Center for Life Science, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Tasic B, Yao Z, Graybuck LT, Smith KA, Nguyen TN, Bertagnolli D, Goldy J, Garren E, Economo MN, Viswanathan S, Penn O, Bakken T, Menon V, Miller J, Fong O, Hirokawa KE, Lathia K, Rimorin C, Tieu M, Larsen R, Casper T, Barkan E, Kroll M, Parry S, Shapovalova NV, Hirschstein D, Pendergraft J, Sullivan HA, Kim TK, Szafer A, Dee N, Groblewski P, Wickersham I, Cetin A, Harris JA, Levi BP, Sunkin SM, Madisen L, Daigle TL, Looger L, Bernard A, Phillips J, Lein E, Hawrylycz M, Svoboda K, Jones AR, Koch C, Zeng H. Shared and distinct transcriptomic cell types across neocortical areas. Nature. 2018 Nov:563(7729):72-78. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0654-5. Epub 2018 Oct 31 [PubMed PMID: 30382198]

Briscoe SD, Ragsdale CW. Homology, neocortex, and the evolution of developmental mechanisms. Science (New York, N.Y.). 2018 Oct 12:362(6411):190-193. doi: 10.1126/science.aau3711. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30309947]

Freund HJ. Somatosensory and motor disturbances in patients with parietal lobe lesions. Advances in neurology. 2003:93():179-93 [PubMed PMID: 12894408]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRoux FE, Djidjeli I, Durand JB. Functional architecture of the somatosensory homunculus detected by electrostimulation. The Journal of physiology. 2018 Mar 1:596(5):941-956. doi: 10.1113/JP275243. Epub 2018 Jan 19 [PubMed PMID: 29285773]

Nguyen JD, Duong H. Neurosurgery, Sensory Homunculus. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31751031]

Schlosser G, Musser J, Arendt D. Editorial - Development and evolution of sensory cells and organs. Developmental biology. 2017 Nov 1:431(1):1-2. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2017.09.007. Epub 2017 Sep 8 [PubMed PMID: 28889956]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKhazipov R, Milh M. Early patterns of activity in the developing cortex: Focus on the sensorimotor system. Seminars in cell & developmental biology. 2018 Apr:76():120-129. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2017.09.014. Epub 2017 Sep 9 [PubMed PMID: 28899717]

De Reuck JL. Pathophysiology of carotid artery disease and related clinical syndromes. Acta chirurgica Belgica. 2004 Feb:104(1):30-4 [PubMed PMID: 15053461]

Tamura R, Yoshida K, Toda M. Current understanding of lymphatic vessels in the central nervous system. Neurosurgical review. 2020 Aug:43(4):1055-1064. doi: 10.1007/s10143-019-01133-0. Epub 2019 Jun 18 [PubMed PMID: 31209659]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGradwell MA, Boyle KA, Callister RJ, Hughes DI, Graham BA. Heteromeric α/β glycine receptors regulate excitability in parvalbumin-expressing dorsal horn neurons through phasic and tonic glycinergic inhibition. The Journal of physiology. 2017 Dec 1:595(23):7185-7202. doi: 10.1113/JP274926. Epub 2017 Oct 19 [PubMed PMID: 28905384]

Tamè L, Braun C, Holmes NP, Farnè A, Pavani F. Bilateral representations of touch in the primary somatosensory cortex. Cognitive neuropsychology. 2016 Feb-Mar:33(1-2):48-66. doi: 10.1080/02643294.2016.1159547. Epub 2016 Jun 17 [PubMed PMID: 27314449]

Campero M, Hughes R, Orellana P, Bevilacqua JA, Guiloff RJ. Spinal cord infarction with ipsilateral segmental neuropathic pain and flaccid paralysis. A functional role for human afferent ventral root small sensory fibres. Journal of the neurological sciences. 2018 Dec 15:395():84-87. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2018.09.037. Epub 2018 Oct 1 [PubMed PMID: 30300819]

MacDonald DB, Dong C, Quatrale R, Sala F, Skinner S, Soto F, Szelényi A. Recommendations of the International Society of Intraoperative Neurophysiology for intraoperative somatosensory evoked potentials. Clinical neurophysiology : official journal of the International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology. 2019 Jan:130(1):161-179. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2018.10.008. Epub 2018 Nov 14 [PubMed PMID: 30470625]

Willis WD Jr, Westlund KN. The role of the dorsal column pathway in visceral nociception. Current pain and headache reports. 2001 Feb:5(1):20-6 [PubMed PMID: 11252134]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMarini F, Ferrantino M, Zenzeri J. Proprioceptive identification of joint position versus kinaesthetic movement reproduction. Human movement science. 2018 Dec:62():1-13. doi: 10.1016/j.humov.2018.08.006. Epub 2018 Aug 29 [PubMed PMID: 30172030]

Plaisier MA, Smeets JB. Object size can influence perceived weight independent of visual estimates of the volume of material. Scientific reports. 2015 Dec 2:5():17719. doi: 10.1038/srep17719. Epub 2015 Dec 2 [PubMed PMID: 26626051]

Momjian-Mayor I, Baron JC. The pathophysiology of watershed infarction in internal carotid artery disease: review of cerebral perfusion studies. Stroke. 2005 Mar:36(3):567-77 [PubMed PMID: 15692123]

Torvik A. The pathogenesis of watershed infarcts in the brain. Stroke. 1984 Mar-Apr:15(2):221-3 [PubMed PMID: 6701929]

Freund HJ. The parietal lobe as a sensorimotor interface: a perspective from clinical and neuroimaging data. NeuroImage. 2001 Jul:14(1 Pt 2):S142-6 [PubMed PMID: 11373146]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKropf E, Syan SK, Minuzzi L, Frey BN. From anatomy to function: the role of the somatosensory cortex in emotional regulation. Revista brasileira de psiquiatria (Sao Paulo, Brazil : 1999). 2019 May-Jun:41(3):261-269. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2018-0183. Epub 2018 Dec 6 [PubMed PMID: 30540029]

Binkofski F, Kunesch E, Classen J, Seitz RJ, Freund HJ. Tactile apraxia: unimodal apractic disorder of tactile object exploration associated with parietal lobe lesions. Brain : a journal of neurology. 2001 Jan:124(Pt 1):132-44 [PubMed PMID: 11133793]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence