Introduction

Rattlesnakes are found throughout the Americas. They exist in almost every state of the U.S., except Alaska and Hawaii, and include snakes in the genera Crotalus and Sistrurus within the subfamily Crotalinae, commonly known as pit vipers. Other venomous snake genera within this subfamily include Lanceheads (Bothrops), Copperheads/Cottonmouths (Agkistrodon), and Asian Palm Pit Vipers (Trimeresurus). Their primary defense mechanism is to hide, but will also rattle and hiss to scare away predators. If they are further challenged, they can bite and envenomate with potentially deadly effects. Knowing the common snakes in one’s area is important in managing a snake bite appropriately.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The morbidity and mortality associated with snake bites are usually due to the envenomation. Snakebite wounds usually do not become infected due to the relative inhibitory effect of the venom on microorganisms. Humans are often bitten when inadvertently stepping on snakes or by moving too close to them while they are in hiding. Usually, a rattle gives away their presence, but there have been rattlesnakes noted to have a dysfunctional tail, possibly due to human selection of exterminating rattling snakes in highly populated areas. Most deaths related to snake bites are due to immediate anaphylactic reactions or failure to seek medical attention for anti-venom administration. Snakebites often result from improper handling or interaction with snakes for leisure. Unfortunately, bites are common in professional snake handlers.[1]

Epidemiology

The vast majority (>99%) of snakebites that occur in the United States are from pit vipers, of which the majority (56.3%) occur from rattlesnakes.[2] The mortality rate is higher with rattlesnake bites compared to other snake bites. In the United States, approximately 9,000 people per year suffer a snake bite, but only five deaths occur. Interestingly, poison center data shows that one in 736 patients who suffer a rattlesnake bite actually dies. Oftentimes, the victim of a rattlesnake bite is a young intoxicated male. Rattlesnakes are found in varying climates in both North and South America.[3]

Pathophysiology

The symptoms from a snake bite are related to the envenomation. Rattlesnakes have hollow fangs in the anterior mouth that inject venom into subcutaneous tissue. Rarely, intravenous injection occurs, but when it does, rapid onset of systemic effects occur which may be fatal. Crotalid venom causes necrosis due to toxic tissue enzymes. It also causes increased permeability of cell membranes, which leads to an increased local spread of the venom. Crotalid venom has both fibrinolytic and protein C activation effects causing coagulopathy in patients. Although most crotalid envenomations often have little neurotoxic effects, particular rattlesnake species, such as the timber rattlesnakes (Crotalus horridus) and Mohave rattlesnakes (Crotalus scutulatus) are two of the known exceptions to this trend. Mohave rattlesnake envenomation is known for producing cranial nerve dysfunction, weakness, and paralysis [4], whereas the venom from timber rattlesnakes has been shown to induce myokymia, an involuntary quivering of muscles or muscle fibers in localized areas.[5]

Toxicokinetics

Crotalid venom consists of a complex mixture of over 50 different identified proteins, metals, and macromolecules, each with various effects. Together, they cause various local, hematologic, neurologic, and systemic effects in envenomed victims. As each component can affect multiple organ systems, it would be inaccurate to rigidly classify them as simply tissue-toxic or neurotoxic.[6] Two of the most well-studied components include phospholipase A2 toxins and metalloproteinases.

Phospholipase A2 toxins are particularly variable and can have myotoxic, anticoagulant, and neurotoxic effects.[7] One proposed mechanism by which phospholipase A2 exerts its neurotoxic effect is by inhibiting neuromuscular transmission at the presynaptic level by blockade of presynaptic calcium-channels of the neuromuscular junction. This may lead to paralysis of a muscle group if present in high enough concentrations. Phospholipases are also thought to damage platelet membranes, inducing platelet destruction, resulting in thrombocytopenia.[4]

Metalloproteinases are thought to be major contributors to local tissue destruction and hemorrhage. One proposed mechanism of promoting hemorrhage includes its effects on capillary beds by cleaving peptide bonds of basement membrane components, affecting the interaction between the basement membrane and endothelial cells. This alters the morphology of endothelial cells, inducing gaps to be formed through which extravasation occurs. In addition to hemorrhage, venom metalloproteinases induce myonecrosis in skeletal muscle secondary to ischemia stemming from the bleeding and reduced perfusion. Additionally, metalloproteinases can induce the release of TNF-α, mediating a prominent local inflammatory response that characterizes snakebite envenomations.[8]

Despite numerous well-performed studies over the last several decades, many aspects of snake venom toxicity are still not clearly defined. More research is required to truly elucidate the specific receptors and molecules behind this process.

History and Physical

Rattlesnake bite victims may present with a variety of local and systemic symptoms. Fang marks are usually identifiable at the patient’s bite site. Local symptoms include localized pain, swelling, and bleeding from the bite site. In more severe cases, local tissue necrosis and ecchymosis can occur. Systemic symptoms include angioedema, bleeding from other orifices including hematemesis and hematochezia, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, dyspnea, and anaphylaxis.[9]

A thorough history should also include the patient’s or bystanders’ description of the snake that might help identify it as venomous or non-venomous. However, the identification of a snake from a patient’s account is often not possible. One should also inquire about any medical co-morbidities such as inherited coagulopathies, immunocompromised states, and the use of anticoagulation/anti-platelet medications.

Evaluation

Although the diagnosis of a snake bite is clinical, and there is no diagnostic test to diagnose or identify the species causing the envenomation, laboratory bloodwork is helpful to guide management. Bloodwork should be performed for all snake bites and should include:

- CBC

- Serum Chemistry

- Coagulation Panel

- Fibrinogen

- Creatine Kinase

A urinalysis can be helpful to evaluate for myoglobinuria, which can help assess for rhabdomyolysis if a creatine kinase value is not readily available. While an x-ray of the bite wound is not necessary, it may be prudent if there is a suspicion of a foreign body or a fracture that may have occurred while escaping the snake. Upon initial evaluation, the leading edge of the swelling and redness surrounding the bite site should be marked. Limbs should be evaluated for neurovascular status. Frequent reassessments for progressive swelling should be performed.

Grading the envenomation can help with the decision to administer antivenin.

Minimal Envenomation (no antivenin indicated)

- Swelling, pain, and ecchymosis limited to the site of the bite

- No systemic signs

- Normal coagulation parameters or isolate mild alterations without clinically relevant bleeding

Moderate Envenomation

- Swelling, pain, and ecchymosis involving less than full extremity or extending < 50 cm in adults

- Systemic symptoms present, such as vomiting, mild hypotension, mild tachycardia

- Abnormal coagulation parameters without clinically relevant bleeding

Severe Envenomation

- Swelling, pain, and ecchymosis involving an entire extremity (or more) or threatening airway

- Systemic signs including altered mental status and hemodynamic instability

- Abnormal coagulation parameters with clinically relevant bleeding

Treatment / Management

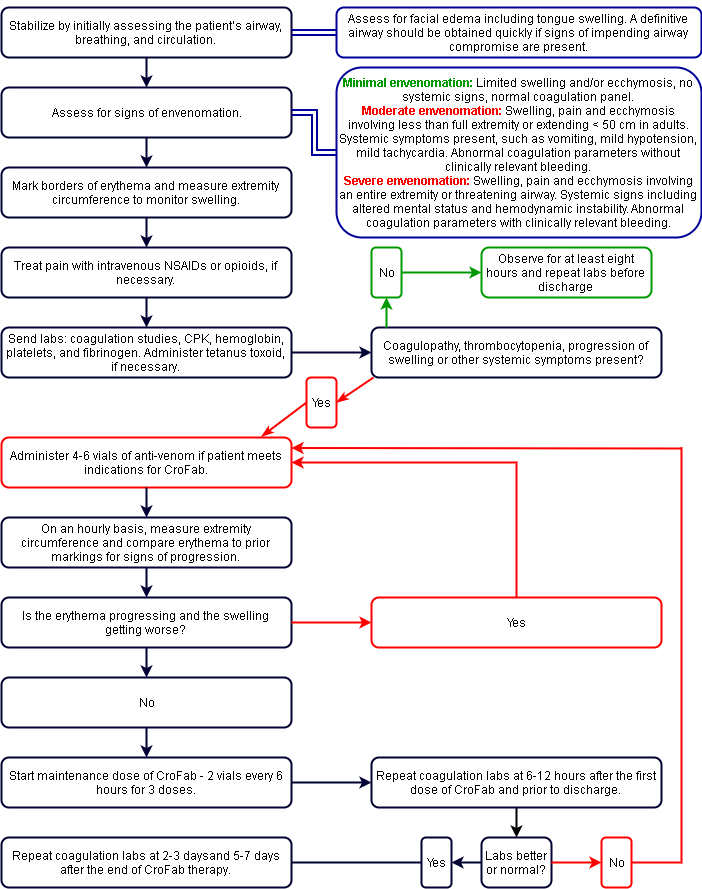

The appropriate management of a rattlesnake bite should begin in the pre-hospital setting. Facilitate the immediate and rapid transport of the patient for evaluation by a qualified medical provider. If possible, immobilize the extremity to reduce the potential dissemination of venom through the lymphatic system, but this should not delay transport. Patients presenting with a snake bite should be stabilized by initially assessing their airway, breathing, and circulation just like any other trauma situation. Some patients may be able to identify the snake that bit them, but this may not always be accurate. Knowing the common snakes in the locality of the patient may help elucidate the likely culprit. In any case, the treatment algorithm for snake envenomation does not change drastically depending on the snake.[10][11][12][13](B3)

Please refer to the attached unified management algorithm for a step-by-step approach to crotaline envenomation.[9](B3)

The leading edge of the swelling and redness surrounding the bite site should be marked and tracked every 15 min-30 min. The extremity should be immobilized to reduce motion, and pain should be treated with IV opioids if necessary. Initial labs are necessary for all snake bites and should include coagulation studies, hemoglobin, platelets, creatine kinase, and fibrinogen. Tetanus should be updated if necessary, and the local poison center should be notified.

Signs of envenomation may vary between presentations but should be assessed in all snakebite victims. Systemic signs include hypotension, bleeding, or oozing from IV sites, vomiting, diarrhea, angioedema, and neurotoxicity. Assessment for facial edema including tongue swelling and respiratory distress should be recognized, and a definitive airway should promptly be obtained if there are concerns for airway compromise.

A patient with minimal signs of envenomation should be monitored for at least eight hours and have a repeat coagulation panel performed to evaluate for delayed coagulopathy before discharge. Patients with progressive swelling, moderate envenomation, or coagulopathy should be given antivenom. In North American there are two Crotalidae Antivenoms approved for use:

Crotalidae Polyvalent Immune Fab Dosing

Crotalidae Polyvalent Immune Fab is derived from 4 snake species (Western Diamondback, Eastern Diamondback, Mojave rattlesnake, and Cottonmouth) and immunized into sheep (ovine-derived). The whole immunoglobin is extracted, affinity purified, and cleaved by papain into the terminal Fab fragment of the immunoglobin. This reduces its size by about 1/3 and allows tissue penetration. However, it is cleared renally, and repeat dosing is usually necessary.

The initial controlling dose consists of 4-6 vials mixed in 250 mL normal saline (NS) administered over one hour (same number of vials for children). Initiate treatment at a rate of 10 mL/hr observing for adverse effects. If none, then increase every few minutes to achieve complete administration in one hour. Observe patients for local swelling and systemic symptoms. If there are signs of progression, then repeat with 4-6 vials over one hour. Do not administer to try to completely normalize abnormal coagulation markers. Repeat until initial control is achieved (local swelling improves or stops, resolution of systemic signs, and resolution of clinically relevant bleeding). After achieving control, maintenance doses of 2 vials every 6 hours for 18 hours are recommended for rattlesnakes, patients with coagulopathy, and those with severe clinical envenomations. This is not usually required for moderate copperhead envenomations. However, if only a controlling dose is used, close and repeated monitoring for progression is important to decide if any additional doses are required. Remember that if recurrent swelling or coagulopathy occurs during maintenance doses, repeat the initial bolus protocol.

Repeat coagulation panel (PT/PTT/INR), fibrinogen, platelets, and hemoglobin on days 2-3 and days 5-7. Recurrent coagulopathy without clinically significant bleeding has been known to occur. Some repeat and follow parameters to normalization. Indications for repeat dosing if coagulopathy occurs between 3 and 7 days after the last dose of antivenom are:

- INR > 3.0

- PTT > 50 seconds

- Platelet Count < 25,000

- Fibrinogen < 50 ug/ml

- Multi-component coagulopathy

Crotalidae Immune F(ab)2 Dosing

Crotalidae Immune F(ab)2 is derived from 2 snakes species (Bothris asper and Crotalus duressis) and immunized in horses (equine-derived). The whole immunoglobin is extracted, purified, and cleaved by pepsin digestion into a fragment with 2 binding sites for venom components - F(ab)2. Despite being derived from horses it is less immunogenic than the original rattlesnake antivenom produced. It is larger in size than Crotalidae Polyvalent Immune Fab and persists in the serum longer with a more sustained duration of the activity, therefore usually not requiring repeat maintenance dosing.

The initial controlling dose consists of 10 vials mixed in 250 mL normal saline (NS) administered over one hour (same number of vials for children). The initial infusion rate for the first 10 minutes should start at 25 to 50 ml/hr, then if no adverse reaction occurs the remained of the 250 ml solution can be given over 1 hour.[14]

It is best to evaluate the number fo each of the antivenoms available and not mix loading and maintenance doses between the two products.

In rare severe envenomations, a repeat dose of 10 vials of Crotalidae Immune F(ab)2 may be needed.

Differential Diagnosis

- Anaphylaxis

- Deep vein thrombosis

- Extremity vascular trauma

- Scorpion Envenomation

- Septic shock

- Serum sickness

- Wasp stings

- Wound care

- Wound infection

Prognosis

Although rattlesnakes are considered more deadly than other pit vipers, the mortality rate associated with rattlesnake envenomations is relatively low, particularly in the setting of prompt medical therapy. U.S. Poison Control Center data from 1983 through 2007 suggests a case-fatality rate for patients affected by rattlesnake bites to be approximately 1 death per 736 patients.[1] More recently, data from the North American Snakebite Registry (NASBR), a national database of detailed, prospectively collected information regarding snake envenomation in the United States, documented 256 rattlesnake bites from January 1, 2013, through December 31, 2015. There were no reported deaths. However, rattlesnake bites were associated with higher proportions of longer hospital stays (>72 hours) compared to other species including copperheads cottonmouths, and coral snakes.[2] Although the mortality is low, there is still significant morbidity associated with rattlesnake toxicity.

Complications

Following a rattlesnake envenomation, complications can occur as a result of the envenomation itself or from its therapy.

Hypersensitivity: A feared complication associated with treatment using Crotalidae polyvalent immune Fab is anaphylaxis or anaphylactoid reactions. Delayed hypersensitivity reactions or serum sickness can also occur. Serum sickness may be treated with a 5 to 7-day course of oral steroids.[15]

Necrosis: Tissue necrosis is the most well-known complication associated with rattlesnake envenomations. One study performed in Arizona included 77 patients with upper extremity rattlesnake bites, of which approximately 40% demonstrated evidence of tissue necrosis.[16] In severe cases, operative debridement or amputation may be necessary.

Infection: Although tissue necrosis is associated with infection. However, infection without tissue necrosis is very uncommon in Crotalid envenomations, estimated to be approximately 3% in one study.[17]

Rhabdomyolysis: Due to the ability of rattlesnake venom to induce myonecrosis, rhabdomyolysis can occur, and with it, associated kidney injury. If CPK is rising reassess the extremity for signs of compartment syndrome, which usually will respond to additional antivenom administration.

Delayed venom effects: Even after initial control, a delayed-onset of one or more venom manifestations, including local swelling occurs in approximately half of the patients treated with antivenin.[18] A delayed onset or recurrence of coagulopathy can occur up to 2 weeks following initial control. Repeat dosing with antivenom may be required. Untreated this could predispose patients to the development of delayed major bleeding.[19]

Compartment syndrome: Compartment syndrome is a rare occurrence in rattlesnake envenomations.[12] These cases will likely resolve with antivenin administration and conservative medical management.[20] However, a minority may require a surgical fasciotomy.

Consultations

Whenever possible, the management of a rattlesnake bite should be performed in conjunction with a local toxicology team or personnel from the regional Poison Control Center. Appropriate surgical services should also be consulted for complications that will require operative management.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Once bitten by a rattlesnake, patients should promptly seek treatment at the nearest emergency department. Despite being popular in the media, patients and family members should AVOID performing any of the following:

- Attempting to kill or capture the offending snake for identification

- Attempting to transport the snake, even if dead

- Applying a tourniquet proximal to the wound

- Application of ice to the bite site

- Attempting to suck the venom out of the bite wound either with a commercial device or by cutting the wound open

- Treating the venom with electric shocks to the bite site

Pearls and Other Issues

Progression of angioedema is unpredictable as it may progress beyond presentation or may start regressing soon after presentation.[21] Elevated protime and/or decreased platelets and fibrinogen levels are also signs of envenomation. Coagulopathy responds to antivenin treatment, but the thrombocytopenia may persist.[22] Life-threatening bleeding is rare despite severe coagulopathy and thrombocytopenia. Platelet or fresh frozen plasma (FFP) transfusion should be avoided except when there is life-threatening bleeding because antivenin is the definitive treatment.

If no signs of envenomation are present, the patient should be observed for at least six hours, and labs should be repeated before discharge. If the patient develops signs during the observation period or presents with signs of envenomation, erythema, and swelling should be marked, measured, and tracked for progression. Prophylactic antibiotics are not indicated for snake bites as they have an extremely low likelihood of infection owing to the proteolytic properties of snake venom.

Overall Indications for Crotalidae Polyvalent Immune Fab or F(ab)2 Antivenom

- Indicated for moderate or severe envenomations only, not minimal

- Swelling that is progressing, crossing a major joint, and/or is more than minimal

- Any systemic symptoms

- Any coagulopathy such as increased protime, or decreased platelet count or fibrinogen

Antivenom will help local symptoms and coagulopathy, and local symptoms are used to monitor response to therapy. Cessation in the progression of swelling and erythema is reassuring.

Worsening angioedema is not a sign of the failure of treatment with Crotalidae Polyvalent Immune Fab. It is not expected to reduce or stop the progression of angioedema. Typically, the angioedema resolves with supportive care.

Coagulation studies will improve with antivenom treatment, but persistent thrombocytopenia has been noted despite Crotalidae Polyvalent Immune Fab treatment and is not considered the failure of treatment. Other systemic signs are expected to improve with treatment as well. Local swelling and pain may persist for weeks to months despite therapy.

Crotalidae Polyvalent Immune Fab is contraindicated in a patient with a known allergy to sheep protein, in which case Crotalidae Polyvalent Immune F(ab)2 can be administered. Crotalidae Polyvalent Immune F(ab)2 is contraindicated with a known allergy to horse protein, in which case Crotalidae Polyvalent Immune Fab should be used. Crotalidae Polyvalent Immune Fab use is associated with an 8% incidence of immediate hypersensitivity and a 13% incidence of serum sickness (which is rare and almost always clinically insignificant). Serum sickness can be treated with a short course of prednisone.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The diagnosis and management of rattlesnake bite are best performed with an interprofessional team that includes the emergency department physician, toxicologist, poison control, surgeon, internist, and intensivist. The appropriate management should begin in the pre-hospital setting. Facilitate the immediate and rapid transport of the patient for evaluation by a qualified medical provider. Immobilize the extremity to reduce the potential dissemination of venom through the lymphatic system, but this should not delay transport. Patients presenting with a snake bite should be stabilized by initially assessing their airway, breathing, and circulation just like any other trauma presentation. All patients must be monitored by the nurse until stable. Those who are asymptomatic may be discharged after a period of observation. Those with signs of envenomation need admission to the ICU for close clinical and biochemical monitoring.[23][24][10]

The prognosis for patients treated promptly is good.

Media

References

Epidemiology of severe and fatal rattlesnake bites published in the American Association of Poison Control Centers' Annual Reports., Walter FG,Stolz U,Shirazi F,McNally J,, Clinical toxicology (Philadelphia, Pa.), 2009 Aug [PubMed PMID: 19640239]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRuha AM,Kleinschmidt KC,Greene S,Spyres MB,Brent J,Wax P,Padilla-Jones A,Campleman S, The Epidemiology, Clinical Course, and Management of Snakebites in the North American Snakebite Registry. Journal of medical toxicology : official journal of the American College of Medical Toxicology. 2017 Dec [PubMed PMID: 28975491]

Snakebite injuries treated in United States emergency departments, 2001-2004., O'Neil ME,Mack KA,Gilchrist J,Wozniak EJ,, Wilderness & environmental medicine, 2007 Winter [PubMed PMID: 18076294]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCorbett B,Clark RF, North American Snake Envenomation. Emergency medicine clinics of North America. 2017 May [PubMed PMID: 28411931]

Vohra R,Cantrell FL,Williams SR, Fasciculations after rattlesnake envenomations: a retrospective statewide poison control system study. Clinical toxicology (Philadelphia, Pa.). 2008 Feb [PubMed PMID: 18259958]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGold BS,Dart RC,Barish RA, Bites of venomous snakes. The New England journal of medicine. 2002 Aug 1 [PubMed PMID: 12151473]

Gutiérrez JM,Lomonte B, Phospholipases A2: unveiling the secrets of a functionally versatile group of snake venom toxins. Toxicon : official journal of the International Society on Toxinology. 2013 Feb [PubMed PMID: 23025922]

Gutiérrez JM,Rucavado A, Snake venom metalloproteinases: their role in the pathogenesis of local tissue damage. Biochimie. 2000 Sep-Oct [PubMed PMID: 11086214]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceUnified treatment algorithm for the management of crotaline snakebite in the United States: results of an evidence-informed consensus workshop., Lavonas EJ,Ruha AM,Banner W,Bebarta V,Bernstein JN,Bush SP,Kerns WP 2nd,Richardson WH,Seifert SA,Tanen DA,Curry SC,Dart RC,, BMC emergency medicine, 2011 Feb 3 [PubMed PMID: 21291549]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTanen D,Ruha A,Graeme K,Curry S, Epidemiology and hospital course of rattlesnake envenomations cared for at a tertiary referral center in Central Arizona. Academic emergency medicine : official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. 2001 Feb; [PubMed PMID: 11157295]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLefkowitz RY,Taylor J,Balfe D, Reality bites: a case of severe rattlesnake envenomation. Journal of intensive care medicine. 2013 Sep-Oct; [PubMed PMID: 22588374]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRodriguez-Acosta A,Aguilar I, Toxoid preparation from the venom of Crotalus durissus cumanensis (South American rattle snake). The Journal of tropical medicine and hygiene. 1987 Feb; [PubMed PMID: 3820358]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBrazil OV, Neurotoxins from the South American rattle snake venom. Taiwan yi xue hui za zhi. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association. 1972 Jul 28; [PubMed PMID: 4269955]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMascarenas DN,Fullerton L,Smolinske SC,Warrick BJ,Seifert SA, Comparison of F(ab'){sub}2{/sub} and Fab antivenoms in rattlesnake envenomation: First year's post-marketing experience with F(ab'){sub}2{/sub} in New Mexico. Toxicon : official journal of the International Society on Toxinology. 2020 Aug 5; [PubMed PMID: 32763251]

LoVecchio F,Klemens J,Roundy EB,Klemens A, Serum sickness following administration of Antivenin (Crotalidae) Polyvalent in 181 cases of presumed rattlesnake envenomation. Wilderness & environmental medicine. 2003 Winter [PubMed PMID: 14719854]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHeise CW,Ruha AM,Padilla-Jones A,Truitt Hayek C,Gerkin RD, Clinical predictors of tissue necrosis following rattlesnake envenomation. Clinical toxicology (Philadelphia, Pa.). 2018 Apr [PubMed PMID: 28885114]

Clark RF,Selden BS,Furbee B, The incidence of wound infection following crotalid envenomation. The Journal of emergency medicine. 1993 Sep-Oct [PubMed PMID: 8308237]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDart RC,Seifert SA,Boyer LV,Clark RF,Hall E,McKinney P,McNally J,Kitchens CS,Curry SC,Bogdan GM,Ward SB,Porter RS, A randomized multicenter trial of crotalinae polyvalent immune Fab (ovine) antivenom for the treatment for crotaline snakebite in the United States. Archives of internal medicine. 2001 Sep 10 [PubMed PMID: 11525706]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBoyer LV,Seifert SA,Clark RF,McNally JT,Williams SR,Nordt SP,Walter FG,Dart RC, Recurrent and persistent coagulopathy following pit viper envenomation. Archives of internal medicine. 1999 Apr 12 [PubMed PMID: 10218750]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGold BS,Barish RA,Dart RC,Silverman RP,Bochicchio GV, Resolution of compartment syndrome after rattlesnake envenomation utilizing non-invasive measures. The Journal of emergency medicine. 2003 Apr [PubMed PMID: 12676299]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSchaeffer TH,Khatri V,Reifler LM,Lavonas EJ, Incidence of immediate hypersensitivity reaction and serum sickness following administration of Crotalidae polyvalent immune Fab antivenom: a meta-analysis. Academic emergency medicine : official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. 2012 Feb; [PubMed PMID: 22320362]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRefractory thrombocytopenia despite treatment for rattlesnake envenomation., Gold BS,Barish RA,Rudman MS,, The New England journal of medicine, 2004 Apr 29 [PubMed PMID: 15115843]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWigginton JB, Snake, rattle, and roll. Journal of the Mississippi State Medical Association. 2013 Mar; [PubMed PMID: 23705324]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMoorman CT 3rd,Moorman LS,Goldner RD, Snakebite in the tarheel state. Guidelines for first aid, stabilization, and evacuation. North Carolina medical journal. 1992 Apr; [PubMed PMID: 1594053]