Introduction

Paroxysmal spells might represent events originating from the central nervous system, cardiac disturbances, psychiatric causes, or might be from other etiologies. Syncope, convulsive concussion, convulsive syncope, rigors, movement disorders, sleep-related events, and psychogenic nonepileptic seizures are all in the differential diagnosis of a transient event with movements. Epileptic seizures constitute one type of paroxysmal event.[1]

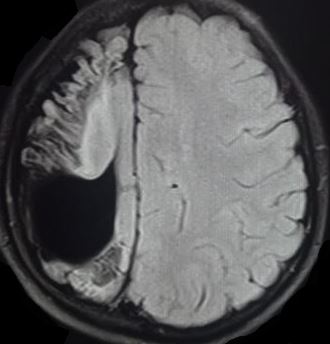

An epileptic seizure is a transient occurrence with signs or symptoms due to abnormal excessive and synchronous neuronal activity in the brain. There are many different types of seizures. Current classification designates two large categories - partial or generalized. In a partial seizure, one area of the cortex is thought to be activated initially and may show simple symptoms such as a motor or sensory phenomena. Partial seizures may rapidly secondarily generalize and spread to involve all cortical areas. Generalized seizures result from diffuse cortical activation at seizure onset. See Image. Seizure From Cortical Changes and Porencephalic Cyst. The most common seizure type in adults is partial-onset seizures with rapid secondary generalization.[2]

Seizures with dyscognitive features, also known as complex partial seizures, are associated with altered awareness or consciousness. These may have minimal motor manifestations such as lip-smacking or small amplitude extremity movements and may present as an isolated confusional state.

Epilepsy, by definition, is a condition of recurrent unprovoked seizures. Determining whether a first seizure or recurrent seizures are provoked or unprovoked is fundamentally essential for diagnosis and treatment.

Epileptic syndromes serve to condense clinical information into useful nomenclature. Localization-related is used in this terminology to indicate seizures that arise from pathology in a localizable brain area. Idiopathic epilepsy is associated with no symptoms other than seizures. In symptomatic epilepsy, seizures reflect underlying identifiable brain disease. Cryptogenic refers to seizure disorders suspected to be symptomatic of underlying brain disease but are without definitive proof of the underlying cause. Specialists usually diagnose an epileptic syndrome.[3]

Status epilepticus is defined as an enduring epileptic condition. There are as many types of status epilepticus are there are types of seizures. Generalized convulsive status epilepticus is a medical emergency. Current definitions define status epileptics as a single generalized convulsion lasting greater than five minutes or a series of generalized seizures without full return of consciousness.[4]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Seizures may be either provoked or unprovoked. Provoked seizures, also known as acute symptomatic seizures, may result from electrolyte disorders, toxins, head injury, infectious processes, vascular anomalies, tumors or other mass lesions, and many other causes. A listing of provoked causes of seizures is lengthy and could include complications of almost any disease process. Some common causes are listed below:

- Electrolyte disturbances (hypoglycemia, hyponatremia, hypernatremia, hypocalcemia, others)

- Acute toxic effects (antidepressants, sympathomimetics, others)

- Withdrawal syndromes (ethanol, benzodiazepines, others)

- Irregularity with prescribed antiepileptic medications

- Sepsis

- CNS infections

- Hypoxic brain injury

- Traumatic brain injury

- Stroke ischemic or hemorrhagic

- Neoplasm

- Inflammatory (lupus cerebritis, anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis, others)

- Fever

- Sleep deprivation

Epilepsy occurs because of a predisposition to seizures from genetic susceptibility or a chronic pathologic process. By definition, unprovoked seizures occur in the absence of provocative causes or more than seven days after an acute injury or insult such as stroke or brain hemorrhage. Recurrent unprovoked seizures define epilepsy.

Of patients in United States general hospitals presenting with generalized convulsive status epilepticus, roughly one-fourth are patients with epilepsy with breakthrough seizures, medication irregularity, or new-onset epilepsy; one-fourth are patients with ethanol-related seizures, and one-half are patients with seizures that are provoked by a variety of medical conditions.[5]

Epidemiology

The age-adjusted incidence of epilepsy in North America ranges between 16 out of 100,000 and 51 out of 100,000 person-years. The age-adjusted prevalence ranges from 2.2 of 1000 to 41 of 1000, depending on the reporting country. Partial epilepsy may constitute up to two-thirds of incident epilepsies. Incidence increases in lower socioeconomic populations.[6]

About 25% to 30% of new-onset seizures are thought to be provoked or secondary to another cause.

Epilepsy incidence is highest in younger and older age groups and increases steadily after 50 years of age. The most common cause of seizures and epilepsy in older people is cerebrovascular disease.[7]

Pathophysiology

Everyone has some propensity to have seizures. The concept of a seizure threshold means that each individual exists on a seizure susceptibility continuum with many factors influencing that susceptibility. Medications, genetic factors, electrolyte abnormalities, sleep state, infections, brain inflammation, or injury from many causes may lead to an individual crossing that threshold with a resulting seizure.

On a cellular level, seizures start with the excitation of susceptible cerebral neurons, which leads to synchronous discharges of progressively larger groups of connected neurons. Neurotransmitters are undoubtedly involved. Glutamate is the most common excitatory neurotransmitter, and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) is an important inhibitory neurotransmitter. An imbalance of excess excitation and decreased inhibition initiates the abnormal electrical activity. These electrical paroxysmal depolarization shifts (PDS) seem to trigger epileptiform activity. Increased activation or decreased inhibition of such discharges could result in seizures. The part of the brain affected often reflects in the clinical signs or symptoms of the seizure.[3]

Generalized convulsive status epilepticus is accompanied by systemic changes of lactic acidosis, increased catecholamine levels, hyperthermia, respiratory compromise, and other systemic alterations.[8][9][10] However, the ongoing excessive electrical activity that occurs with status epilepticus is damaging to the brain.[11] There is an evolution of generalized convulsive status epilepticus from continuous or discrete seizures to a condition of minimal or no motor activity. The electrical activity reflected by EEG evolves as well.[12] The result may be a type of nonconvulsive generalized status epilepticus.

History and Physical

As with many medical conditions, history is key in assessment and will guide further evaluations. The first question posed to the caregiver is whether the event was a seizure or some other type of transient event. A sudden alteration in consciousness with associated motor movements is the common description of a convulsive seizure. For generalized seizures with associated motor movements, the convulsion typically has a stiffening or tonic phase followed by clonic movements - rhythmic phased motor movements. There may be a noise or cry at the onset of the seizure. Some patients will describe a prodrome or aura before the event. Urinary incontinence may or may not be present. Tongue biting, if present, is most frequently lateral. Following a generalized tonic-clonic seizure, patients will have some transient alteration consciousness referred to as the postictal state. There are many types of seizures other than generalized convulsions, and any transient alteration of consciousness or unusual behavior or individualized perception might conceivably represent a type of seizure.

Key historical points include history with attention to the history of seizures, medication use, past medical history, and social history, especially any history of alcohol or illicit drug use. Any history of immunosuppression or malignancy is critical to discover. Frequently there will be a history of unresponsive spells that, in retrospect, might be seizures. Events leading up to the seizure are quite important, and friends, family, or coworkers may have crucial historical information. For the patient with known epilepsy, an obvious question would be to ask if there has been any irregularity with medication use.

Physical examination should include a general physical examination and a neurologic examination with attention to the detection of any focal deficits. If someone observes the convulsion, they may see open eyes, no response to verbal or painful stimulation during the event, and rhythmic in-phase motor movements are consistent with a generalized tonic-clonic seizure.

For patients with a suspected seizure and persistent alteration in consciousness, the possibility of transformed status epilepticus should merit consideration. Sometimes termed subtle status epilepticus, the motor movements of this type of nonconvulsive status epilepticus may only be nystagmic eye movements, facial twitching, extremity twitches, or in some cases, no motor movement at all.[12][13]

Evaluation

Further clinical evaluations are guided by history and physical examination. If the clinician believes that the event is a seizure, the first question is whether it is provoked or unprovoked. Typically laboratory work, including electrolytes, is obtained. Lumbar puncture should merit consideration in patients with fever, a history of immunosuppression, or other factors suggesting possible central nervous system infection.

Neuroimaging is often obtained and is of higher yield based on historical factors or focal findings on the neurologic examination. Imaging is a recommendation whenever there is suspicion of an acute intracranial process in patients with a history of acute head trauma, history of malignancy, immunocompromise, fever, persistent headache, anticoagulation use, age older than 40 years, or focal seizure onset.[14][15]

For a healthy adult patient who has returned to baseline normal neurologic status who has apparently had a first seizure, determining serum glucose and sodium is recommended. Pregnancy testing is a recommendation in women of childbearing age.[1] Commonly additional labs and neuroimaging are necessary.

Electroencephalography (EEG) is a biomarker for epilepsy. Focal or generalized epileptiform discharges constitute the EEG hallmark of seizure activity. Frequently EEG is obtained as a risk-stratification tool for a patient with a seizure of possibility of seizures. Should the EEG show epileptiform or other abnormalities, management might change.

Persistent alteration of consciousness or continuing seizures will dictate additional testing such as neuroimaging and other serologic tests. If nonconvulsive status epilepticus is a consideration, arrangements for neurologic consultation and EEG are in order.[1]

Treatment / Management

Patients with reversible causes of seizures, such as hypoglycemia, may be discharged after appropriate interventions and with consideration for a safe home environment. For patients with a history of epilepsy who have returned to baseline mental status, adjusting the medication regimen and follow-up with other providers may be necessary. Testing for medication levels may be appropriate if available for the particular antiepileptic drug. If the patient has been noncompliant with an antiepileptic drug regimen, medications should be resumed.

Patients with alcohol withdrawal seizures represent another group of patients who may be discharged after appropriate treatment and a period of observation. Treatment of alcohol withdrawal seizures deserves special mention since episodic treatment with lorazepam has shown to decrease the risk of recurrence.[16](A1)

A first unprovoked seizure in an adult who has returned to a normal neurological baseline often does not require initiation of medical treatment.[1] Caution regarding engaging in potentially hazardous activities involves discussion with the patient until follow-up, additional testing, and reassessment occurs.

If deciding to start drug therapy, many medications are options to treat a chronic seizure disorder or epilepsy as first-line medication or adjunctive medications. Selection may be guided by side effects and in consultation with a neurologist. They can be grouped based on their mechanism of action and include sodium channel blockers (carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, eslicarbazepine, phenytoin, fosphenytoin, lamotrigine, lacosamide, and zonisamide), and agonists of GABA receptor (benzodiazepine and barbiturates). Other drugs with associated mechanisms include GABA reuptake inhibitors (tiagabine), inhibitors of GABA-transaminase (vigabatrin), glutamate antagonists (topiramate, felbamate, perampanel), medications with binding to synaptic vesicle 2A protein (levetiracetam, brivaracetam), and drugs with multiple mechanisms (gabapentin, pregabalin, valproic acid).

For the patient with generalized convulsive status epilepticus, immediate treatment of the seizures should begin while stabilization and other diagnostic procedures commence. Supportive care with attention to airway, breathing, and circulation issues are vital. Benzodiazepines such as diazepam, midazolam, or lorazepam are acceptable as the first-line medications for continuing seizures. Recommended dosage varies, but accepted regimens for adults are listed below.[17][18] Respiratory depression is a common side effect, and patients will need careful monitoring. Underdosing of benzodiazepines is common, and the provider should be certain that there has been an adequate dose of a benzodiazepine given before adding additional medications.[19]

- Lorazepam 4 mg IV; repeat once in 5 to 10 minutes if seizures continue

- Midazolam 10 mg IM or IV; repeat once in 5 to 10 minutes if seizures continue

- Diazepam 10 mg IV; repeat once in 10 minutes if seizures continue

The best second-line medication is unclear even after completing a highly anticipated randomized trial of benzodiazepine refractory status epilepticus- the established status epilepticus treatment trial (ESETT). Second-line medications include fosphenytoin, valproate, levetiracetam, and others. Doses used in the ESETT study are listed below, given with an infusion time of ten minutes. The dosing of these medications in this study was higher than doses typically used in clinical practice. Clinicians have noted similar incidences of adverse effects with these medications, and no one drug was superior to the others.[20](A1)

- Fosphenytoin 20PE/kg (up to 1500 phenytoin equivalents)

- Valproate 40mg/kg (up to 300 mg)

- Levetiracetam 60/mg (up to 4500 mg)

Should generalized convulsive status epilepticus continue, often advanced airway management is necessary. Blood pressure support may be necessary. The best treatment for refractory status epilepticus is unknown, but options include propofol, barbiturates (pentobarbital), or continuous benzodiazepine infusions in addition to other anesthetic medications. ICU admission will be necessary with continuous EEG monitoring.[18][21][22][23][24](A1)

Differential Diagnosis

Spells resembling seizures stem from many different processes. One key differentiation is between a syncopal event and a seizure. Both events have an abrupt onset, but a syncopal event often has a provocative cause, the loss of consciousness is brief, and return to full consciousness is prompt without a confusional state. Incontinence may be present with either type of event. At times syncope is associated with motor movements mimicking a seizure.[25]

Another distinction often involves distinguishing seizures from psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Please see that chapter for further information.

A partial of seizure mimics follows:[26]

- Syncope, convulsive syncope

- Psychogenic nonepileptic seizures

- Convulsive concussion

- Movement disorders

- Sleep-related movements

- Convulsive concussion

Prognosis

The prognosis of patients with seizures depends mostly on any underlying cause. Patients with seizures from remedial medical or toxicologic causes should do well with the management of those issues.

In other patients with acute symptomatic seizures, the prognosis is related to the disease process. Obviously, as a group, patients with neoplastic causes of seizures or hypoxic brain injury will not fare well compared to many patients with metabolic causes of seizures.

The prognosis of a patient with a single unprovoked seizure has been well delineated. Unprovoked seizures, by definition, have no established cause after clinical evaluation. If basic investigations, including appropriate laboratory work, imaging, and perhaps EEG, are unremarkable, estimates of the recurrence rate of another unprovoked seizure within five years are between one-third and one-half. However, if there is a second or third unprovoked seizure, the risk of further seizures increases to about three-quarters.[27][28]

Complications

In addition to using antiepileptic medications, the treatment of seizures aims at correcting any identifiable causative process. Care is needed to prevent any secondary brain injury, which may include advanced respiratory and cardiovascular support. Monitoring is necessary to detect hypotension and hypoxia and steps taken to correct those conditions when recognized.

Common complications may include traumatic injuries such as tongue lacerations or scalp lacerations.[29]

Convulsive status epilepticus leads to brain damage on the cellular level and may itself be epileptogenic. Transformed or subtle generalized convulsive status epilepticus or nonconvulsive seizures detected by EEG monitoring in critically ill patients may also contribute to brain injury.[30][31]

Deterrence and Patient Education

As with any medical condition, prevention is preferable to reactive interventions. Some conditions leading to provoked seizures may permit interventions before the development of a seizure. Clearly, with provoked seizures related to alcohol withdrawal or drug abuse, efforts should be made for appropriate actions pertaining to those disorders.

One study of patients presenting to emergency departments with seizure-related complaints found that roughly two-thirds of those with antiepileptic drug levels obtains had sub-therapeutic levels.[29] Counseling regarding medical compliance in patients with epilepsy and avoiding any triggers such as sleep-deprivation are crucial.

Patents with spells or seizures of unknown etiology should be counseled not to drive or operate dangerous machinery. Reporting requirements vary state-to-state.

Pearls and Other Issues

Most generalized seizures terminate in less than five minutes, and a seizure of longer duration or serial seizures without regaining full consciousness in between defines status epilepticus. Whether status epilepticus is from provoked causes or unprovoked causes, initial treatment is similar.

A benzodiazepine such as diazepam, midazolam, or lorazepam is accepted as first-line medications. Underdosing is common when compared to guideline recommendations. Side effects are primarily respiratory depression and primarily related to the rate of administration. However, underdosing benzodiazepines may contribute to reduced efficacy, potentially resulting in prolongation of status epilepticus.[19]

Outcomes following generalized convulsive status epilepticus depend on any underlying cause of the seizures and the duration of the status epilepticus.

For patients with seizures who require endotracheal intubation for airway management, neuromuscular blockade with paralysis will obscure signs of seizures. Stat EEG, if available, is recommended. If in doubt, medication administration with the presumption that seizures are continuing seems prudent in the short term.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Clear communication between interprofessional team members is essential since patients' clinical status may abruptly change. This interprofessional team includes primary care clinicians (including PAs and NPs), specialists (e.g., neurologists), nurses, mental health specialists, and pharmacists, who must operate collaboratively as a unit and share open communication regarding the patient's condition to achieve optimal outcomes. [Level 5]

Most patients will have a single, brief, uncomplicated event and return to full consciousness. Detection of any underlying cause of the seizure or seizures is important so that appropriate therapy or counseling is available.

There are many causes of seizures, but regardless of the cause, the basic initial treatment is similar. Seizure patients all require supportive care and assessment of airway, breathing, and circulation with appropriate interventions. Other interventions, including medications and critical care interventions, may be necessary for patients with a prolonged seizure or continuing seizures. Communication and coordination with other health care providers are essential to optimize team response.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Huff JS, Melnick ER, Tomaszewski CA, Thiessen ME, Jagoda AS, Fesmire FM, American College of Emergency Physicians. Clinical policy: critical issues in the evaluation and management of adult patients presenting to the emergency department with seizures. Annals of emergency medicine. 2014 Apr:63(4):437-47.e15. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.01.018. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24655445]

Fisher RS, Acevedo C, Arzimanoglou A, Bogacz A, Cross JH, Elger CE, Engel J Jr, Forsgren L, French JA, Glynn M, Hesdorffer DC, Lee BI, Mathern GW, Moshé SL, Perucca E, Scheffer IE, Tomson T, Watanabe M, Wiebe S. ILAE official report: a practical clinical definition of epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2014 Apr:55(4):475-82. doi: 10.1111/epi.12550. Epub 2014 Apr 14 [PubMed PMID: 24730690]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHuff JS, Fountain NB. Pathophysiology and definitions of seizures and status epilepticus. Emergency medicine clinics of North America. 2011 Feb:29(1):1-13. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2010.08.001. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21109098]

Lowenstein DH,Bleck T,Macdonald RL, It's time to revise the definition of status epilepticus. Epilepsia. 1999 Jan [PubMed PMID: 9924914]

Lowenstein DH, Alldredge BK. Status epilepticus at an urban public hospital in the 1980s. Neurology. 1993 Mar:43(3 Pt 1):483-8 [PubMed PMID: 8450988]

Banerjee PN, Filippi D, Allen Hauser W. The descriptive epidemiology of epilepsy-a review. Epilepsy research. 2009 Jul:85(1):31-45. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2009.03.003. Epub 2009 Apr 15 [PubMed PMID: 19369037]

Sen A, Jette N, Husain M, Sander JW. Epilepsy in older people. Lancet (London, England). 2020 Feb 29:395(10225):735-748. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)33064-8. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32113502]

Orringer CE, Eustace JC, Wunsch CD, Gardner LB. Natural history of lactic acidosis after grand-mal seizures. A model for the study of an anion-gap acidosis not associated with hyperkalemia. The New England journal of medicine. 1977 Oct 13:297(15):796-9 [PubMed PMID: 19702]

Simon RP. Physiologic consequences of status epilepticus. Epilepsia. 1985:26 Suppl 1():S58-66 [PubMed PMID: 3922751]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChen JW, Wasterlain CG. Status epilepticus: pathophysiology and management in adults. The Lancet. Neurology. 2006 Mar:5(3):246-56 [PubMed PMID: 16488380]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFountain NB, Lothman EW. Pathophysiology of status epilepticus. Journal of clinical neurophysiology : official publication of the American Electroencephalographic Society. 1995 Jul:12(4):326-42 [PubMed PMID: 7560021]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTreiman DM, Walton NY, Kendrick C. A progressive sequence of electroencephalographic changes during generalized convulsive status epilepticus. Epilepsy research. 1990 Jan-Feb:5(1):49-60 [PubMed PMID: 2303022]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTrinka E, Cock H, Hesdorffer D, Rossetti AO, Scheffer IE, Shinnar S, Shorvon S, Lowenstein DH. A definition and classification of status epilepticus--Report of the ILAE Task Force on Classification of Status Epilepticus. Epilepsia. 2015 Oct:56(10):1515-23. doi: 10.1111/epi.13121. Epub 2015 Sep 4 [PubMed PMID: 26336950]

Harden CL, Huff JS, Schwartz TH, Dubinsky RM, Zimmerman RD, Weinstein S, Foltin JC, Theodore WH, Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Reassessment: neuroimaging in the emergency patient presenting with seizure (an evidence-based review): report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2007 Oct 30:69(18):1772-80 [PubMed PMID: 17967993]

. Practice parameter: neuroimaging in the emergency patient presenting with seizure (summary statement). American College of Emergency Physicians, American Academy of Neurology, American Association of Neurological Surgeons, American Society of Neuroradiology. Annals of emergency medicine. 1996 Jul:28(1):114-8 [PubMed PMID: 8669731]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceD'Onofrio G, Rathlev NK, Ulrich AS, Fish SS, Freedland ES. Lorazepam for the prevention of recurrent seizures related to alcohol. The New England journal of medicine. 1999 Mar 25:340(12):915-9 [PubMed PMID: 10094637]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBrophy GM, Bell R, Claassen J, Alldredge B, Bleck TP, Glauser T, Laroche SM, Riviello JJ Jr, Shutter L, Sperling MR, Treiman DM, Vespa PM, Neurocritical Care Society Status Epilepticus Guideline Writing Committee. Guidelines for the evaluation and management of status epilepticus. Neurocritical care. 2012 Aug:17(1):3-23. doi: 10.1007/s12028-012-9695-z. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22528274]

Claassen J, Riviello JJ Jr, Silbergleit R. Emergency Neurological Life Support: Status Epilepticus. Neurocritical care. 2015 Dec:23 Suppl 2():S136-42. doi: 10.1007/s12028-015-0172-3. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26438462]

Sathe AG, Tillman H, Coles LD, Elm JJ, Silbergleit R, Chamberlain J, Kapur J, Cock HR, Fountain NB, Shinnar S, Lowenstein DH, Conwit RA, Bleck TP, Cloyd JC. Underdosing of Benzodiazepines in Patients With Status Epilepticus Enrolled in Established Status Epilepticus Treatment Trial. Academic emergency medicine : official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. 2019 Aug:26(8):940-943. doi: 10.1111/acem.13811. Epub 2019 Jul 18 [PubMed PMID: 31161706]

Kapur J, Elm J, Chamberlain JM, Barsan W, Cloyd J, Lowenstein D, Shinnar S, Conwit R, Meinzer C, Cock H, Fountain N, Connor JT, Silbergleit R, NETT and PECARN Investigators. Randomized Trial of Three Anticonvulsant Medications for Status Epilepticus. The New England journal of medicine. 2019 Nov 28:381(22):2103-2113. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1905795. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31774955]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHantus S. Epilepsy Emergencies. Continuum (Minneapolis, Minn.). 2016 Feb:22(1 Epilepsy):173-90. doi: 10.1212/CON.0000000000000285. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26844736]

Welch RD, Nicholas K, Durkalski-Mauldin VL, Lowenstein DH, Conwit R, Mahajan PV, Lewandowski C, Silbergleit R, Neurological Emergencies Treatment Trials (NETT) Network Investigators. Intramuscular midazolam versus intravenous lorazepam for the prehospital treatment of status epilepticus in the pediatric population. Epilepsia. 2015 Feb:56(2):254-62. doi: 10.1111/epi.12905. Epub 2015 Jan 17 [PubMed PMID: 25597369]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSilbergleit R, Durkalski V, Lowenstein D, Conwit R, Pancioli A, Palesch Y, Barsan W, NETT Investigators. Intramuscular versus intravenous therapy for prehospital status epilepticus. The New England journal of medicine. 2012 Feb 16:366(7):591-600. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1107494. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22335736]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBetjemann JP, Lowenstein DH. Status epilepticus in adults. The Lancet. Neurology. 2015 Jun:14(6):615-24. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00042-3. Epub 2015 Apr 20 [PubMed PMID: 25908090]

Lin JT, Ziegler DK, Lai CW, Bayer W. Convulsive syncope in blood donors. Annals of neurology. 1982 May:11(5):525-8 [PubMed PMID: 7103429]

Webb J, Long B, Koyfman A. An Emergency Medicine-Focused Review of Seizure Mimics. The Journal of emergency medicine. 2017 May:52(5):645-653. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2016.11.002. Epub 2016 Dec 19 [PubMed PMID: 28007363]

Musicco M, Beghi E, Solari A, Viani F. Treatment of first tonic-clonic seizure does not improve the prognosis of epilepsy. First Seizure Trial Group (FIRST Group). Neurology. 1997 Oct:49(4):991-8 [PubMed PMID: 9339678]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHauser WA, Rich SS, Lee JR, Annegers JF, Anderson VE. Risk of recurrent seizures after two unprovoked seizures. The New England journal of medicine. 1998 Feb 12:338(7):429-34 [PubMed PMID: 9459646]

Huff JS, Morris DL, Kothari RU, Gibbs MA, Emergency Medicine Seizure Study Group. Emergency department management of patients with seizures: a multicenter study. Academic emergency medicine : official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. 2001 Jun:8(6):622-8 [PubMed PMID: 11388937]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYoung GB, Claassen J. Nonconvulsive status epilepticus and brain damage: further evidence, more questions. Neurology. 2010 Aug 31:75(9):760-1. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181f32141. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20805520]

Laccheo I, Sonmezturk H, Bhatt AB, Tomycz L, Shi Y, Ringel M, DiCarlo G, Harris D, Barwise J, Abou-Khalil B, Haas KF. Non-convulsive status epilepticus and non-convulsive seizures in neurological ICU patients. Neurocritical care. 2015 Apr:22(2):202-11. doi: 10.1007/s12028-014-0070-0. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25246236]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence