Introduction

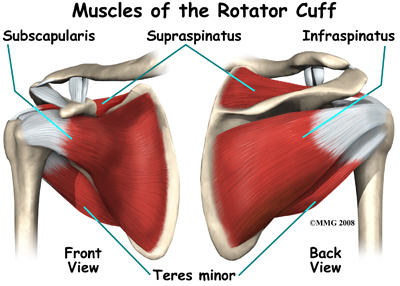

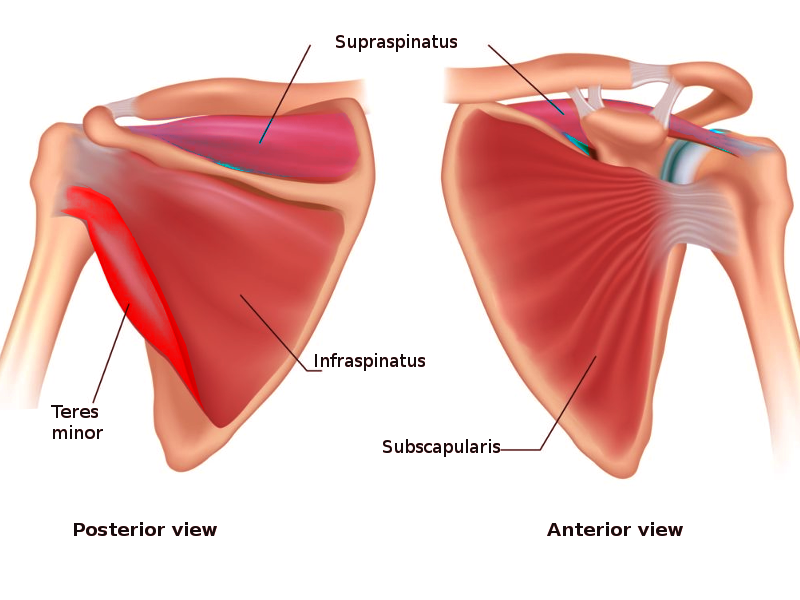

The rotator cuff is a group of muscles in the shoulder that allow a wide range of movement while maintaining the stability of the glenohumeral joint (see Image. Rotator Cuff Muscles). The rotator cuff includes the following muscles[1][2][3]:

- Subscapularis

- Infraspinatus

- Teres minor

- Supraspinatus (see Image. Rotator Cuff Muscles Anatomy)

A helpful mnemonic to remember these muscles is "SITS".

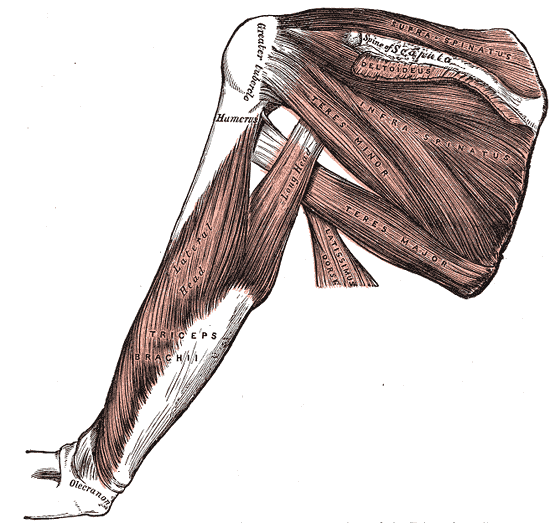

The glenohumeral joint is a ball and socket joint and comprises a large spherical humeral head and a small glenoid cavity. This anatomy makes the joint highly mobile, however, really unstable. Stabilization in the shoulder is provided collectively by the non-contractile tissue of the glenohumeral joint (static stabilizers) such as the capsule, the labrum, the negative intraarticular pressure, and the glenohumeral ligaments; and the contractile tissues (dynamic stabilizers) such as the rotator cuff muscles and the long head of the biceps brachii. See Image. Muscles and Fascia of the Shoulder.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The primary biomechanical role of the rotator cuff is to stabilize the glenohumeral joint by compressing the humeral head against the glenoid. These four muscles arise from the scapula and insert into the humerus. The tendons of the rotator cuff muscles blend with the joint capsule and form a musculotendinous collar that surrounds the posterior, superior, and anterior aspects of the joint, leaving the inferior aspect unprotected. This arrangement is an important factor since most shoulder luxations occur because the humerus slides inferiorly through the unprotected part of the joint. During arm movements, the rotator muscles contract and prevent the sliding of the head of the humerus, allowing full range of motion and providing stability.

Additionally, rotator cuff muscles help in the mobility of the shoulder joint by facilitating abduction, medial rotation, and lateral rotation.

- Subscapularis: Medial (internal) rotation of the shoulder

- Supraspinatus: Abduction of the arm

- Necessary for the initial 0 to 15 degrees of shoulder abduction motion

- The deltoid muscle abducts the arm beyond 15 degrees

- Infraspinatus: Lateral (external) rotation of the shoulder

- Teres Minor: Lateral (external) rotation of the shoulder

During physical examination, each muscle can be evaluated independently based on its specific movements.

Embryology

Mesoderm gives rise to the muscles and ligaments in the body.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The vascular supply to the rotator cuff muscles is mainly via the suprascapular artery, the subscapular artery, and the posterior circumflex humeral artery.

The suprascapular artery is a branch of the thyrocervical trunk (a major branch of the subclavian artery) and originates at the base of the neck. It enters the posterior scapular region superior to the suprascapular foramen (the nerve passes through the foramen) and supplies the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles.

The subscapular artery is the largest branch of the axillary artery. It originates from the third part of the axillary artery, follows the inferior margin of the subscapularis muscle, and then divides into the circumflex scapular artery and the thoracodorsal artery. It gives vascular supply to the subscapularis muscle.

The posterior circumflex humeral artery originates from the third part of the axillary artery in the axilla. It enters the posterior scapular region through the quadrangular space (accompanied by the axillary nerve) and supplies the teres minor muscle.

All lymphatics from the upper limb drain into lymph nodes in the axilla.

Nerves

The subscapular nerve (upper and lower branches) innervates the subscapularis muscle.

- Originate from the posterior cord of the brachial plexus

- C5, C6, C7

The suprascapular nerve innervates the infraspinatus and supraspinatus

- Originates from the superior trunk of the brachial plexus

- Passes through the suprascapular foramen

- C5 and C6

The axillary nerve innervates teres minor

- Originates from the posterior cord of the brachial plexus

- Passes through the quadrangular space into the posterior scapula region

- C5 and C6

Muscles

The subscapularis is the largest component of the posterior wall of the axilla. It prevents the anterior dislocation of the humerus during abduction and medially rotates the humerus. A large bursa separates the muscle from the neck of the scapula [4].

- Origin: subscapular fossa of the scapula

- Insertion: lesser tubercle of the humerus

The supraspinatus muscle is the only muscle of the rotator cuff that is not a rotator of the humerus.

- Origin: supraspinous fossa of the scapula

- Passes above the glenohumeral joint

- Insertion: greater tuberosity of the humerus

The infraspinatus is a powerful lateral rotator of the humerus. The tendon of this muscle is sometimes separated from the capsule of the glenohumeral joint by a bursa.

- Origin: infraspinous fossa of the scapula

- Insertion: greater tuberosity of the humerus, immediately below the supraspinatus.

The teres minor is a narrow and long muscle entirely covered by the deltoid, hardly differentiated from the infraspinatus.

- Origin: lateral border of the scapula (below the infraglenoid tubercle)

- Insertion: greater tuberosity of the humerus, below the infraspinatus tendon.

Clinical Significance

Physical Examination[5]

Rotator cuff muscles can undergo independent evaluation when the patient presents with rotator cuff syndrome.

- Supraspinatus muscle: The evaluation of this muscle is with the Jobe's test, commonly known as the "empty can" test. It is done with a 90 degrees abduction and internal rotation (thumb pointing to the floor) of the arm while pressing down on the arm. The test is positive if this is painful or weak.

- Infraspinatus muscle: Evaluation of this muscle is via lateral rotation against resistance with the elbow flexed and the arm in a neutral abduction/adduction position.

- Teres minor muscle: This muscle's evaluation is with the hornblower's test, done with the arm at 90 degrees abduction, the elbow flexed (90 degrees), and doing a lateral rotation against resistance. The test is positive if this is painful or weak.

- Subscapularis muscle: Evaluating this muscle uses the "lift-off" and the "bear hug" test. In the lift-off test, the patient brings the hands around the back to the lumbar region with the palms facing outward. The test is positive if the patient is unable to lift the hands away from the back. On the Bear hug test, the patient places the ipsilateral palm on the opposite deltoid and tries to resist the examiner pulling it away anteriorly.

Rotator Cuff Syndrome [1][6][7][8]

Rotator cuff syndrome (RCS) describes a spectrum of clinical pathology ranging from minor injuries such as acute rotator cuff tendinitis to advanced/chronic rotator cuff tendinopathy and degenerative conditions.

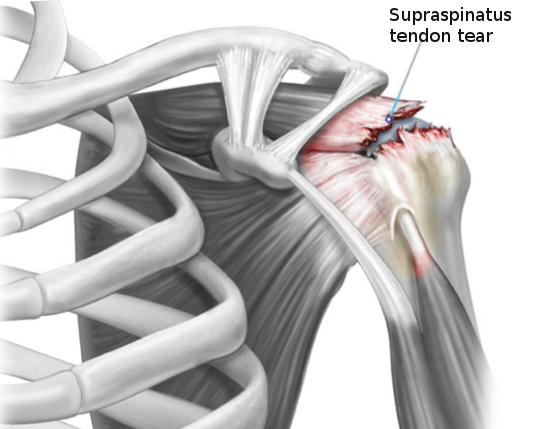

Rotator cuff injuries represent a common cause of shoulder pain. The rotator cuff tendons, particularly the supraspinatus tendon, are uniquely susceptible to the compressive forces of subacromial impingement. Improper athletic technique, poor posture, poor conditioning, and failure of the subacromial bursa to protect the supporting tendons results in a progressive injury from acute inflammation, to calcification, to degenerative thinning, and finally to a tendon tear (see Image. Rotator Cuff Tear).

Rotator cuff (RC) Tendonitis/Tendinosis

Acute or chronic tendinopathic conditions that result from a vulnerable environment for the RC secondary to repetitive eccentric forces and predisposing anatomical/mechanical risk factors.

Shoulder Impingement

A clinical term often used nonspecifically to describe patients experiencing pain/symptoms with overhead activities. It is best to subdivide shoulder impingement into internal and external conditions:

- Internal impingement[9]: Common in overhead-throwing athletes such as baseball pitchers and javelin throwers. Impingement occurs at the posterior/lateral articular side of the cuff as it abuts the posterior/superior glenoid rim and labrum when the shoulder is in maximum abduction and external rotation (i.e., the "late cocking" phase of throwing)

- The term "thrower's shoulder" refers to a common set of anatomic adaptive changes that occur over time in this subset of athletes.

- These adaptive changes include but are not limited to increased humeral retroversion and posterior capsular tightness.

- Glenohumeral internal rotation deficit (GIRD) is a condition resulting from these anatomic adaptations, and GIRD is known to predispose the thrower's shoulder to internal impingement.

- External impingement: a term used synonymously with SIS. External impingement (EI) encompasses etiologies of external compressive sources (i.e., the acromion), leading to subacromial bursitis and bursal-sided injuries to the RC [10].

History and Physical for RCS

The primary complaint is shoulder pain localized on the lateral aspect. It worsens with overhead activities, and patients often describe a painful arc during flexion and abduction at 60 degrees to 120 degrees and report pain at night due to lying on the same side. The presentation can be acute or chronic in onset. Young patients usually have an acute presentation because of a recent traumatic event or significant overexertion (e.g., lifting a heavy box). The function is often significantly impaired. Older patients or patients with repetitive overhead activities present chronically, and the loss of strength and function occurs gradually. The range of motion is normal, with positive provocative tests like Hawkins (pain on passive forced internal rotation of the shoulder). The drop arm test is confirmatory. If weakness is present on shoulder abduction, a rotator cuff tear should be suspected (MRI is the best test for diagnosis of rotator cuff tear).

Treatment for RCS [11]

The American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons (AAOS) suggests patients with rotator cuff problems without tears can be treated conservatively with exercise and NSAIDs. The patient must understand to limit overhead activities and to use ice packs or heating pads. Proper physical therapy effectively treats most patients without subacromial decompression. No difference in outcome has been reported for surgery over physical therapy in several trials. Subacromial injection with steroids showed a short-term benefit in some trials and may improve a patient's compliance with physical therapy. Surgical consultation merits consideration if symptoms do not improve three months after conservative management. Arthroscopic acromioplasty may be a topic to discuss with the patient.

Partial- versus Full-Thickness Rotator Cuff Tears

Etiologies and underlying causes are known to be multifactorial. Degeneration, impingement, and tension overload due to trauma may all lead to rotator cuff tears. Most often, the tears initially begin as partial tears of the supraspinatus tendon. Eventually, they can progress to full-thickness tears including all four of the rotator cuff muscles.

It primarily presents in middle-aged to older patients. Repetitive overhead activities are commonly the reason for younger athletes.

History and Physical

Pain and weakness are the presenting symptoms. Pain is prominent over the lateral deltoid, worsens with overhead activities, and by lying on the side at night. The absence of pain, however, does not exclude the diagnosis because a chunk of patients may also be asymptomatic. In fact, partial thickness tears cause more pain and disability than full-thickness tears. Painful arc test, drop arm test, and weakness in the external rotation is the most common observations on physical examination.

X-rays are usually normal and can help in diagnosing large rotator cuff tears if imaging shows humeral migration over the glenoid, and the patient has a symptomatic shoulder.

MRI can provide key information as to the degree of muscle tear, tendon retraction, and muscle atrophy, which is critical in planning for rotator cuff repair.

Treatment

Conservative treatment with NSAIDs, and most importantly, physical therapy, should be the first attempt at therapy. Surgical treatment with arthroscopy is done in cases of both acute or chronic full-thickness tears since delay can result in significant muscle atrophy, tendon retraction, and poorer surgical results.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Varacallo M, El Bitar Y, Sina RE, Mair SD. Rotator Cuff Syndrome. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30285401]

Varacallo M, El Bitar Y, Mair SD. Rotator Cuff Tendonitis. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30335303]

Cowan PT, Mudreac A, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Back, Scapula. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30285370]

Vosloo M, Keough N, De Beer MA. The clinical anatomy of the insertion of the rotator cuff tendons. European journal of orthopaedic surgery & traumatology : orthopedie traumatologie. 2017 Apr:27(3):359-366. doi: 10.1007/s00590-017-1922-z. Epub 2017 Feb 16 [PubMed PMID: 28204962]

Hippensteel KJ, Brophy R, Smith MV, Wright RW. A Comprehensive Review of Physical Examination Tests of the Cervical Spine, Scapula, and Rotator Cuff. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2019 Jun 1:27(11):385-394. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-17-00090. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30383577]

Wolff AB, Sethi P, Sutton KM, Covey AS, Magit DP, Medvecky M. Partial-thickness rotator cuff tears. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2006 Dec:14(13):715-25 [PubMed PMID: 17148619]

Inderhaug E, Kalsvik M, Kollevold KH, Hegna J, Solheim E. Long-term results after surgical treatment of subacromial pain syndrome with or without rotator cuff tear. Journal of orthopaedics. 2018 Sep:15(3):757-760. doi: 10.1016/j.jor.2018.03.004. Epub 2018 Mar 17 [PubMed PMID: 29946199]

Harrison AK, Flatow EL. Subacromial impingement syndrome. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2011 Nov:19(11):701-8 [PubMed PMID: 22052646]

Gelber JD, Soloff L, Schickendantz MS. The Thrower's Shoulder. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2018 Mar 15:26(6):204-213. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-15-00585. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29443703]

Farfaras S, Sernert N, Rostgard Christensen L, Hallström EK, Kartus JT. Subacromial Decompression Yields a Better Clinical Outcome Than Therapy Alone: A Prospective Randomized Study of Patients With a Minimum 10-Year Follow-up. The American journal of sports medicine. 2018 May:46(6):1397-1407. doi: 10.1177/0363546518755759. Epub 2018 Mar 15 [PubMed PMID: 29543510]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceTashjian RZ. AAOS clinical practice guideline: optimizing the management of rotator cuff problems. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2011 Jun:19(6):380-3 [PubMed PMID: 21628649]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence