Introduction

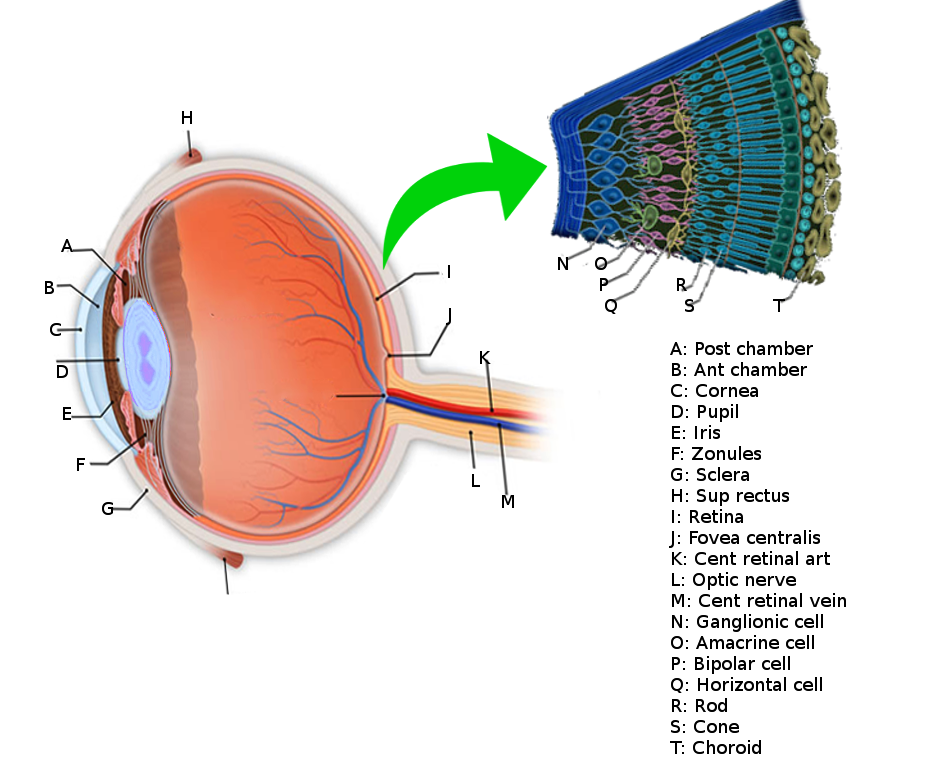

The retina (see Image. Retina Anatomy) is the innermost layer of tissue of the posterior portion of the eye and is composed of multiple cellular layers. The outermost layer called the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), abuts the choroid, and the innermost layer, or the internal limiting membrane (ILM), faces the vitreous cavity.[1] Retinal detachment (RD) occurs when the neurosensory retina separates from the underlying RPE (see Video. Retinal Detachment Video). The photoreceptors lie on the outer portion of the neurosensory retina, and the choroid supplies oxygen and nutrition for the photoreceptors. There are no retinal blood vessels within the fovea, and retinal tissue within this area depends entirely on the choroid for its oxygen requirements. A detachment of the clinical macula (or anatomical fovea) can lead to permanent damage to the photoreceptors in this location. Surgical retina reattachment can potentially retain vision if the macula remains attached. However, vision may remain poor if the macula comes off (redetaches) despite surgical intervention.

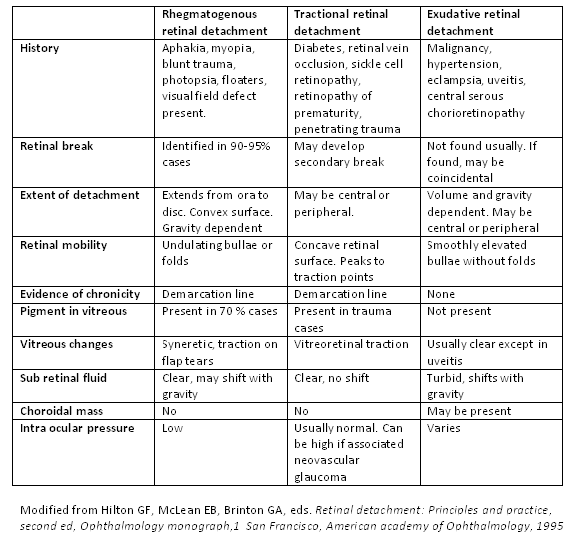

There are 3 categories of RD: rhegmatogenous, tractional, and exudative (see Image. Types of Retinal Detachment).[2] There also may be a combination of types of RD. Rhegmatogenous RDs are the most common, caused by fluid passing from the vitreous cavity via a retinal tear or a break into the potential space between the sensory retina and the RPE (subretinal space). Tractional detachments occur when proliferative membranes contract and elevate the retina. Components of rhegmatogenous and tractional etiologies may also lead to RD. Exudative detachments result from fluid accumulation beneath the sensory retina caused by retinal or choroidal diseases.[3]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

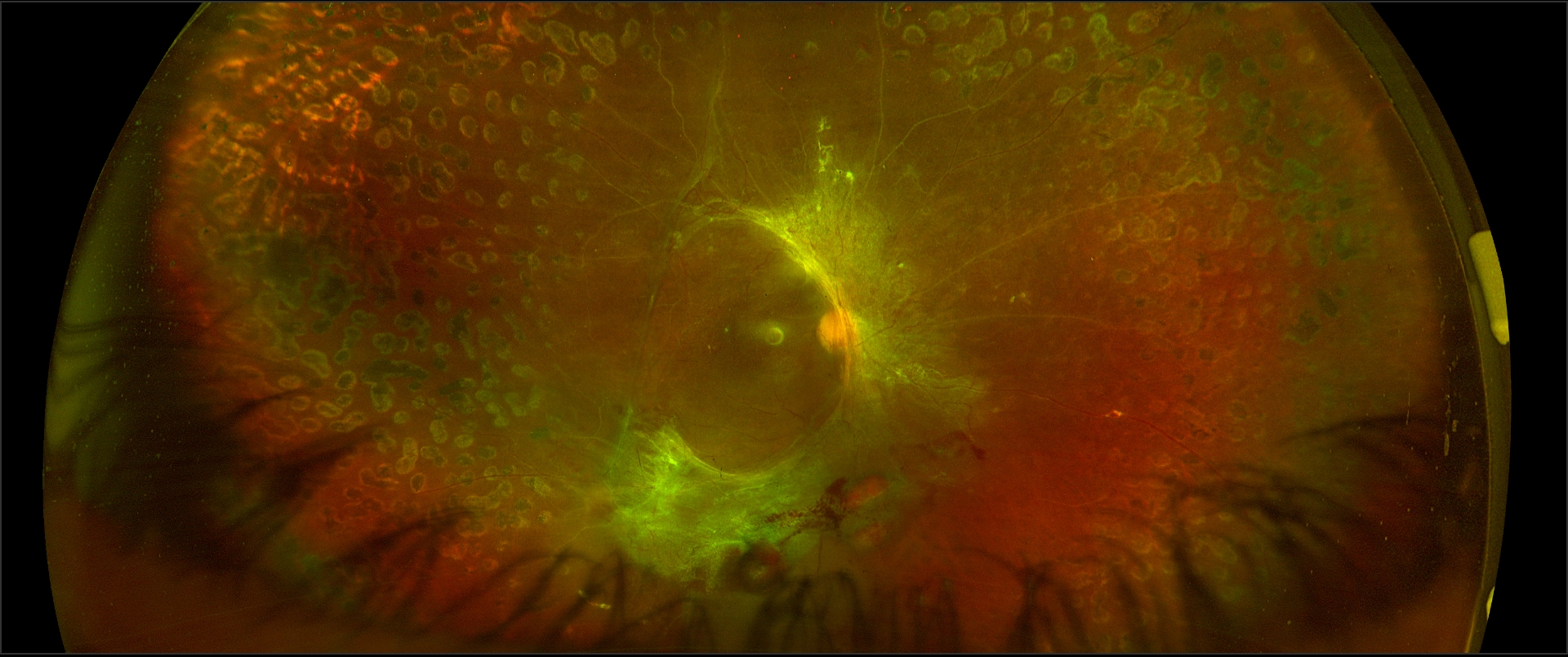

Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment, RRD (see Image. Superotemporal Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment), is associated with a retinal break where liquefied vitreous enters the subretinal space. This process is facilitated by traction over the retinal break that keeps the gap open, ensuring that the entry of liquefied vitreous or fluid to the subretinal space supersedes the RPE pump, which helps absorb the subretinal fluid. Risk factors for RRD include

- Lattice degeneration [4][5][6]

- Retinal breaks

- Retinal holes/tears:

- Atrophic hole

- Operculated hole

- Horseshoe tears (HSTs)

- Giant retinal tears (GRTs)

- Retinal dialysis

- Retinal breaks following necrosis after trauma or infection (retinitis)[7][8]

- Meridional complex

- Snailtrack degeneration (may be a variant of lattice degeneration)[9][10]

- Vitreoretinal tufts:

- Zonular traction tufts

- Cystic retinal tufts

- Pathological myopia

- Macular hole(s) may cause RRD, specifically in pathological myopia with or without vitreomacular traction

- Previous intraocular surgery

- YAG (Yttrium Aluminium Garnet) capsulotomy

- Trauma

- Previous retinal detachment in the other eye

- Fundal coloboma [11]

- Genetic disorders (including Stickler syndrome, Marfan syndrome)

- Retinal necrosis and breaks after infective retinitis (including acute retinal necrosis, cytomegaloviral retinitis)

- Family history

The formation of proliferative membranes causes tractional retinal detachments (TRD). The risk factors for TRD include the following:

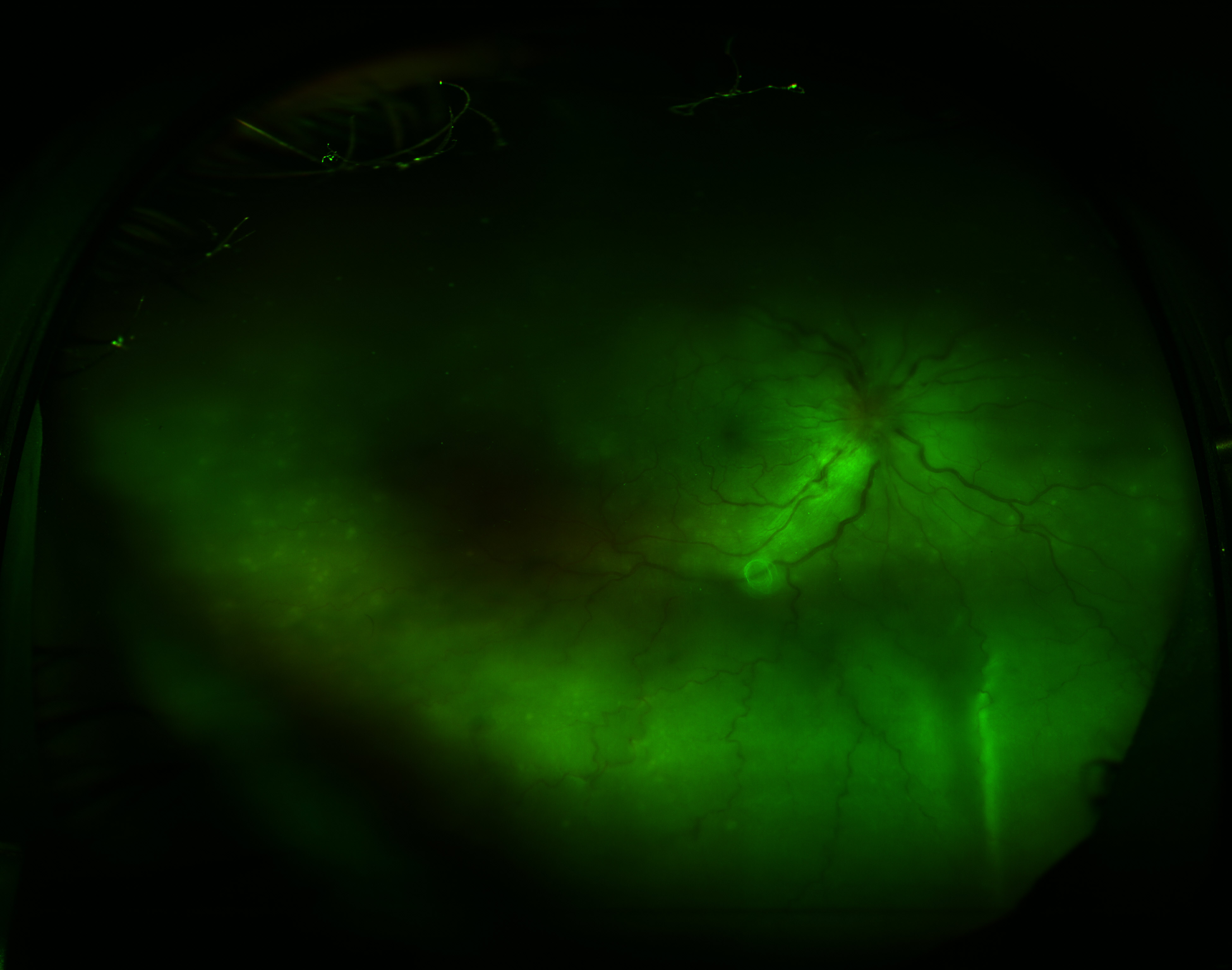

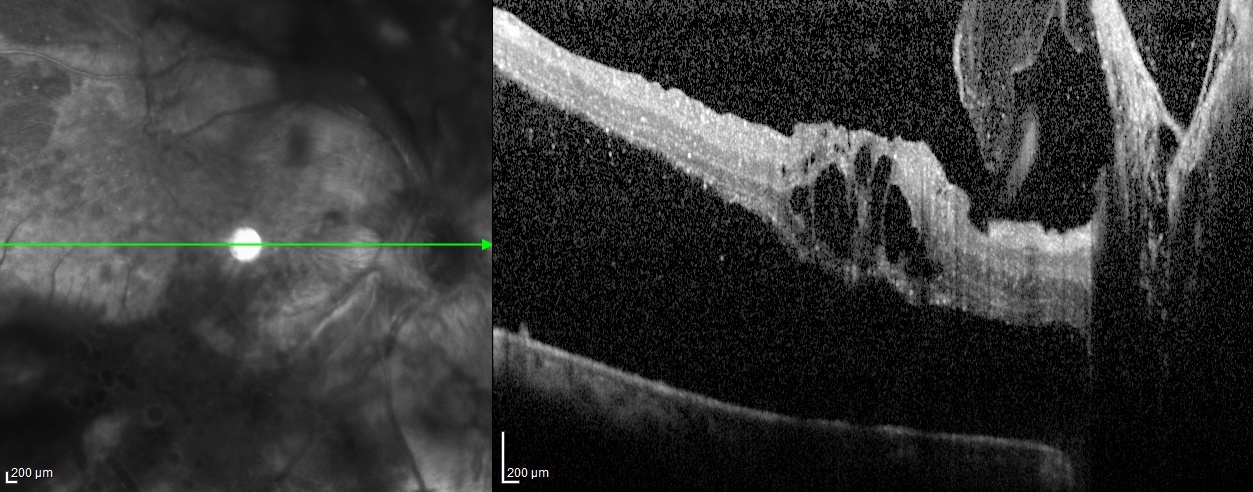

- Proliferative diabetic retinopathy [12][2] (see Image. Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy OCT and Image. Superotemporal Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment)

- Proliferative vitreoretinopathy

- Sickling hemoglobinopathies

- Trauma

- Retinal vein occlusion

- Retinopathy of prematurity

In exudative or serous RD (see Image. Exudative Retinal Detachment in Sympathetic Ophthalmia), fluid enters the subretinal space (in the absence of retinal breaks). The causes of exudative retinal detachments (ERDs) include

- Primary ocular tumors

- Ocular metastases [13]

- Sarcoidosis

- Syphilis [14]

- Toxoplasmosis

- Sympathetic ophthalmia [15][16][17][15]

- Central serous chorioretinopathy (CSCR) [18][19][18]

- Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy

- Tuberculosis [20][21][20]

- Corticosteroid therapy

- Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome

- Pre-eclampsia, eclampsia, or malignant hypertension [22][23][22]

- Organ transplantation

- Optic nerve pit

- Acute retinal necrosis [24]

- Coats disease [25]

Epidemiology

The incidence and risk of RRD vary between study results; one showed 1 in 10,000 individuals, and another showed the annual risk of RRD to be about 6.3 to 17.9 per 100,000 individuals.[26] Males may be at a slightly higher risk than females of getting an RRD.[27] There may be a higher risk of RRD in those of Southeastern Asian descent compared to European White race persons, confounded by the fact that Southeastern Asian populations tended to have a higher risk of myopia and a longer axial length.[28] Results from another study did not find a significant difference in risk factors, postoperative outcomes, and clinical features in patients with retinal detachments between Indian, Malay, and Chinese populations in Singapore.[29]

Pathophysiology

There are 3 classifications of RDs: rhegmatogenous retinal detachment (RRD), tractional retinal detachment (TRD), and exudative retinal detachment (ERD).

An RRD occurs when a tear, break, or hole presents in the retina. When a break occurs, this may allow vitreous to enter the space underneath the neurosensory retina, causing a detachment from the RPE. The fluid continues to enter underneath the retina so that it peels off from the RPE until the entire posterior retina is detached. For an RRD to occur, the following are needed:

- A full-thickness retinal break

- Liquified vitreous, with or without

- Traction over the break [30]

An RRD can occur over hours to months, depending on the location of the detachment. An inferior RRD due to an inferior atrophic retinal hole or inferior retinal dialysis in a young individual usually takes years to involve the fovea and become symptomatic. On the contrary, a superior horseshoe tear can cause rapid progression of superior RRD that involves the fovea early in an older patient with the posterior vitreous detachment (PVD) and liquefied vitreous.[31] An RD can lead to severe vision loss; without surgical intervention, RD can be a permanently blinding condition.

TRDs do not include a break in the neurosensory retina. When proliferative membranes are in the vitreous or on the retinal surface, these membranes can pull on the neurosensory retina. When the force is strong enough, it can cause separation of the neurosensory retina from the underlying RPE.[32]

ERDs also do not involve a break in the neurosensory retina. In these detachments, subretinal fluid accumulates due to fluid exudation from a large lesion, such as a tumor or inflammatory lesion.[33]

History and Physical

Patients with RRD may present with a history of many new-onset floaters. They may also have significant photopsia (flashes of light) in their vision.[34] The patient often presents with progressive or fixed visual field loss, typically starting in the periphery and moving centrally. Other essential aspects of the history include the timing of the onset of the symptoms, if the patient has the same visual loss symptoms in the fellow eye, whether central visual acuity is affected, prior surgery, or previous trauma. The clinician should obtain a complete review of systems and past medical history and take note of the history of myopia or interventions to manage this condition (including LASIK or laser in situ keratomileusis and phakic intraocular lenses).

Essential aspects of the physical exam include obtaining the patient's best-corrected visual acuity of each eye, checking the pupillary reaction of each eye and relative afferent pupillary defect, and confrontational visual field testing.[35][36] Checking the intraocular pressure is also helpful. An RRD with significant breaks with or without serous choroidal detachment (CD) may cause hypotony.

The clinician should complete a slit lamp examination of the anterior segment to look for any abnormalities. A dilated fundoscopic examination should then follow. Significant findings include pigment in the anterior vitreous (Schaffer sign or tobacco dust appearance) or vitreous hemorrhage. An ophthalmologist or optometrist should repeat the fundoscopic examination with indirect ophthalmoscopy with scleral depression so that the entire retina is visualizable up to the ora serrata and the examiner can identify any breaks or tears.[37][38] Use a B-scan ultrasound to evaluate for detachment if areas of the posterior pole are not visible or if there is an entire view obstruction.

TRD may cause gradual vision loss. The clinical features include fibrovascular proliferation or traction over the retina, which pulls the retina and causes the TRD. Usually, there is other evidence of the causative disease, including proliferative diabetic retinopathy and branch retinal venous occlusion.

Inferior RD, which typically shows shifting fluid, is characteristic of exudative retinal detachment. In such patients, the RD, which appears inferior in sitting or standing positions, becomes total RD (or involves the superior retina) in the supine position. In such cases, there are not any retinal breaks, and there is no tobacco dust in the anterior vitreous on slit lamp examination. There might be other evidence of the cause (fibrin with serous pigment epithelial detachment in CSCR, retinal or choroidal mass, or inflammatory condition).

Evaluation

Any patient with suspected RD should undergo a dilated fundoscopic examination with an indirect ophthalmoscope and indentation by an ophthalmologist or optometrist. Other modalities to assist in the diagnosis of RD include ultrasound,[39] CT (computed tomography) scan, and MRI (magnetic resonance imaging).[40] Typically, CT and MRI are not needed for evaluation of RD alone unless suspicion of intraocular mass or malignancy or other indication of the imaging is present. Point-of-care ultrasound in the hands of an experienced provider can be an effective way of diagnosing RD, with one meta-analysis showing a sensitivity of 94.2% and specificity of 96.3%.[41]

On ultrasonogram, RD is differentiated from a vitreous membrane by features that include

- RD has an attachment to both margins of the optic nerve head in a scan going through the optic nerve

- RD usually appears as a thick membrane

- The after-movement of RD is less than a vitreous membrane

- The RD has high echogenicity (100% when the ultrasound beam is perpendicular to the retina compared to the choroid-sclera)

- The RD remains visible even when the machine's sensitivity is lowered (at around 40 decibels)

- The color Doppler ultrasound will show vascularity in RD

If available, optical coherence tomography (OCT) can be an effective way to assess all 3 types of retinal detachments and differentiate a detachment from other retinal pathology.[42]

If a patient has RD that is likely rhegmatogenous, Lincoff rules outlined below, should be followed to find the retinal break:[43]

- In detachments located superotemporally or superonasally, the main break is located within 1.5 clock hours of the highest border 98% of the time.

- In total or superior detachments that fall across the 12:00 meridian, there are two likely possibilities. The first is that the main break is located at 12:00. The second is that the break is a triangle, with the apex of the triangle at the ora serrata, and the sides extend one half-clock hour to either side of 12:00. One of these options occurs 93% of the time.

- For inferior detachments, 95% of the time, the higher side of the attachment indicates which side of the optic nerve at the inferior break lies. For example, if the detachment is higher within the nasal, the break is likely also nasal.

- Detachments that form inferior bullae (inferior bullous RRD) originate from a break superiorly.

Treatment / Management

Management of RRD and TRD is typically surgical. Exudative macular detachments usually have nonsurgical management. The recommendation includes having the patient work with a retinal specialist or an ophthalmologist with additional training in the evaluation and surgical treatment of the posterior portion of the eye.

If the patient has an RRD, the surgeon should identify and seal all retinal breaks or tears. The 3 main techniques used to achieve closure are pars plana vitrectomy, scleral buckle, or pneumatic retinopexy; these techniques can also be combined. Factors that play into the decision of which technique to use include the patient's presentation, surgeon's training, and cost.[44] There are varying opinions on which procedure is the most effective, although there are situations where a specific procedure may be more advantageous to use over another.[45][46][47][48](A1)

A vitrectomy is the mechanical removal of the vitreous gel with a vitrectomy machine. The retinal surgeon typically puts 3 ports through the pars plana portion of the eye; one port is for the lighting, one port is for the vitreous cutter, and one port is for the infusion cannula. The surgeon then removes vitreous tractioning on the retina and uses cryotherapy or laser around retinal breaks or tears using isoexpansile gas (18% SF6 or 12%-14% C3F8) or silicone oil as a tamponade.[49] Though the gases absorb on their own, repeat surgery is needed to remove silicone oil.

A scleral buckle is a silicone band wrapped around the globe permanently, sliding under the extraocular rectus muscles, causing scleral indentation, which closes retinal breaks. Often, a retinal surgeon combines this with a retinopexy procedure (retina reattachment), typically cryopexy.

In pneumatic retinopexy, an intraocular gas bubble is injected into the eye to allow the subretinal fluid to reabsorb and a chorioretinal adhesion to form around the causative break or tear. Various intraocular gases are helpful for tamponade, the most common being air, 0.5- to 0.6-mL SF6 (100%), or 0.3 mL C3F8 (100%). The size of the gas is such that on expansion, the maximum volume (around 1 mL) is less than 25% of the total vitreous volume (4 mL) so that intraocular pressure does not rise much and is controlled medically.[50] SF6 gas expands 2 times, and C3F8 gas expands 4 times.[50] Perform anterior chamber paracentesis before injecting gas to avoid raising intraocular pressure too high. Another calculation of the size of injected 100% SF6 in pneumatic retinopexy is 0.3 mL added to the volume of drained aqueous with anterior chamber paracentesis. Once the gas is in place and retinal apposition occurs, the surgeon performs transconjunctival retinopexy using cryotherapy. Following the procedure, patients may need to reposition so the gas bubble can tamponade the retinal tear. Typically, pneumatic retinopexy is only used in RDs with a single break less than 1 clock hour in size, with the break localizing to the superior 8 clock hours, absence of proliferative vitreoretinopathy, and confidence that all retina breaks or tears have been identified. Laser photocoagulation can be used in place of cryotherapy for retinopexy, and laser typically causes less inflammation than cryotherapy.

In tractional detachments, tractional elements (usually epiretinal or subretinal membranes) must be relieved, typically done with pars plana vitrectomy, but may be combined with scleral buckling as an adjunct.[51]

For serous or exudative retinal detachments, management is nonsurgical. The underlying retinal or choroidal disease or mass should be identified and treated.[3]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnoses for suspected retinal detachment include the following:

- Retinoschisis [52]

- Choroidal effusion or serous choroidal detachment

- Choroidal mass

- Suprachoroidal hemorrhage (hemorrhagic choroidal detachment)

The clinician can differentiate the above with a dilated fundoscopic exam and appropriate imaging techniques. If the patient has a quadrantanopia or hemianopia in both eyes, a cerebrovascular event should be in the differential.[53] RRD should be on the differential for patients who have a TRD.[54] Massive subretinal hemorrhage from various causes, including choroidal neovascular membrane due to age-related macular degeneration, polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy, peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy (PEHCR), blood dyscrasias, anticoagulants, and trauma cause hemorrhagic RD.[55]

Prognosis

The prognosis of RD varies significantly on the type of detachment and patient presentation. For an RRD, one of the most essential prognosticating factors is whether or not the macula remains attached. One study's findings showed that 83% of patients who still had the macula attached had a best-corrected visual acuity of 20/40 or better.[56] If the macula remains attached, the time to surgery does not change the final visual outcome.[57] If the macula is detached, however, the visual prognosis is relatively poor. Around 50% of patients recover to 6/15 or better visual acuity with surgical intervention within the first week.[58] Surgical intervention in individuals with a macula-off detachment should occur within the first week. However, surgery does not have to occur as an emergent case in the first 24 hours. However, some authors suggest that macula-off RDs, if operated within 72 hours, may have "only marginally worse" visual outcomes compared to macula-on retinal detachments; prioritize surgery in such cases.[59] The patient likely will have a worse visual outcome if there is submacular fluid on OCT. The phakic status of a patient does not seem to play a role in visual prognosis after RD.[60] The major factors for good visual prognosis include macula-on status (versus macula-off), low duration of macula-off, and low height of the detached macula.

Tractional RDs have a varied visual prognosis. The final visual outcome depends on the underlying cause of the tractional detachment and if there are confounding issues affecting the vision. Exudative RDs also have variable visual prognoses based on the underlying condition.[61][62]

Complications

Proliferative retinopathy (PVR) occurs in around 8% to 10% of patients with a primary RD repair, constituting the most common cause of repair failure. RPE, glial, and other cells form membranes after they migrate and grow onto the outer and inner surfaces of the retina and vitreous. These membranes often contract, causing equatorial traction, detachment of the non-pigmented epithelium from the pars plana, generalized retinal shrinkage, and fixed retinal folds. The patient may be at higher risk for PVR if they are older, have giant retinal tears, RD involving more than 2 quadrants, vitreous hemorrhage, a choroidal detachment, had a previous RD repair, or if they are using cryotherapy.[63]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Educate patients not to wait to be seen by an ophthalmologist or optometrist if they have changes in their vision. Make patients aware that vision loss from a retinal detachment can be permanent. If patients receive a diagnosis of RRD, surgery will likely be necessary. Educating patients about the surgical process can help alleviate fears about having surgery and may help improve compliance with the treatment, resulting in an optimal surgical outcome; this may be especially important following a pneumatic retinopexy, where they may have to remain in a specific position so that the gas bubble can tamponade the retinal detachment effectively.[64] When intraocular gas is present, patients should avoid air travel as it can cause expansion of the gas bubble and extreme rise of the intraocular pressure with possible permanent optic nerve injury and vision loss.

Prophylaxis to prevent RRD includes laser photocoagulation, cryotherapy, and, in some cases, scleral buckling.[65] According to the preferred practice pattern of the American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO), treating lesions should include the following:

- Treat promptly:

- Acute symptomatic HSTs (acute PVD with flashes/floaters and HSTs)

- Acute symptomatic retinal dialysis

- Usually treated:

- Traumatic retinal breaks

- Consider treatment:

- Asymptomatic HST (without subclinical RRD if signs of chronicity are absent).[66]

Other lesions that need laser include acute symptomatic HST at the edge of the lattice and lattice with subclinical RRD.[67]The prophylactic laser of lattices (with or without holes) should be individualized and considered in patients with only one eye, patients with RD in the other eye, and patients who can not follow up regularly. At least 1 disc diameter of subretinal fluid around the retinal break defines subclinical RRD. However, the subretinal fluid should not reach more than 2 disc diameters posterior to the equator to be called a subclinical RRD. Another definition of subclinical RRD is one in which vision and visual field are not affected.[67]

The prophylactic laser of fundal coloboma to prevent RRD is controversial, though encouraging results with prophylactic lasers have been reported.[11][68] Prophylactic laser in patients with acute retinal necrosis may not prevent retinal detachment.[69]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Excellent communication among allied health professionals working as an interprofessional team is essential to treating patients with RD, especially since patient outcomes can be time-sensitive. A careful medical history is necessary during the evaluation of RD. As with any acute vision loss, consult the ophthalmologist immediately. An RRD constitutes an ocular emergency, and clinicians should consult with the ophthalmologist promptly.[70] The clinician should assess both eyes' best-corrected visual acuity, pupil reactivity, and confrontational visual fields. An ophthalmologist with retinal surgical training should ultimately direct treatment. Patients often make the referral to receive treatment for a retinal detachment faster if they have a macula on retinal detachment.[71]

Refer patients to a retinal specialist or tertiary care center as soon as possible, as a referral from optometrists via general practitioners and local ophthalmic clinics can delay treatment, leading to reduced outcomes.[72]

The care of the patient may involve a multitude of medical disciplines. Decreasing and disabling vision may require the involvement of physical and occupational therapy. Depending on the underlying etiology of the retinal detachments, specialists, including but not limited to endocrinology, neurology, infectious disease, rheumatology, or hematology/oncology, may need to evaluate the patient. Specific ophthalmologic subspecialties necessary for consultation include the retina, uveitis, ocular oncology, pediatric ophthalmology, neuro-ophthalmology, and glaucoma. Regardless of the underlying cause, the patient must follow up with their regular ophthalmologist or vitreoretinal surgeon to prevent future complications and help control risk factors. Opthalmology specialty-trained nurses can assist in surgical and non-surgical treatment by helping with surgical prep and post-operative care. Nurses can counsel patients and act as a point of contact and bridge between the clinician and patient, monitoring treatment progress in all cases and reporting to the treating clinician. Open and transparent interprofessional communication between team members can enhance patient outcomes.

Media

(Click Video to Play)

Retinal Detachment Video

Contributed by Harry J. Goett

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

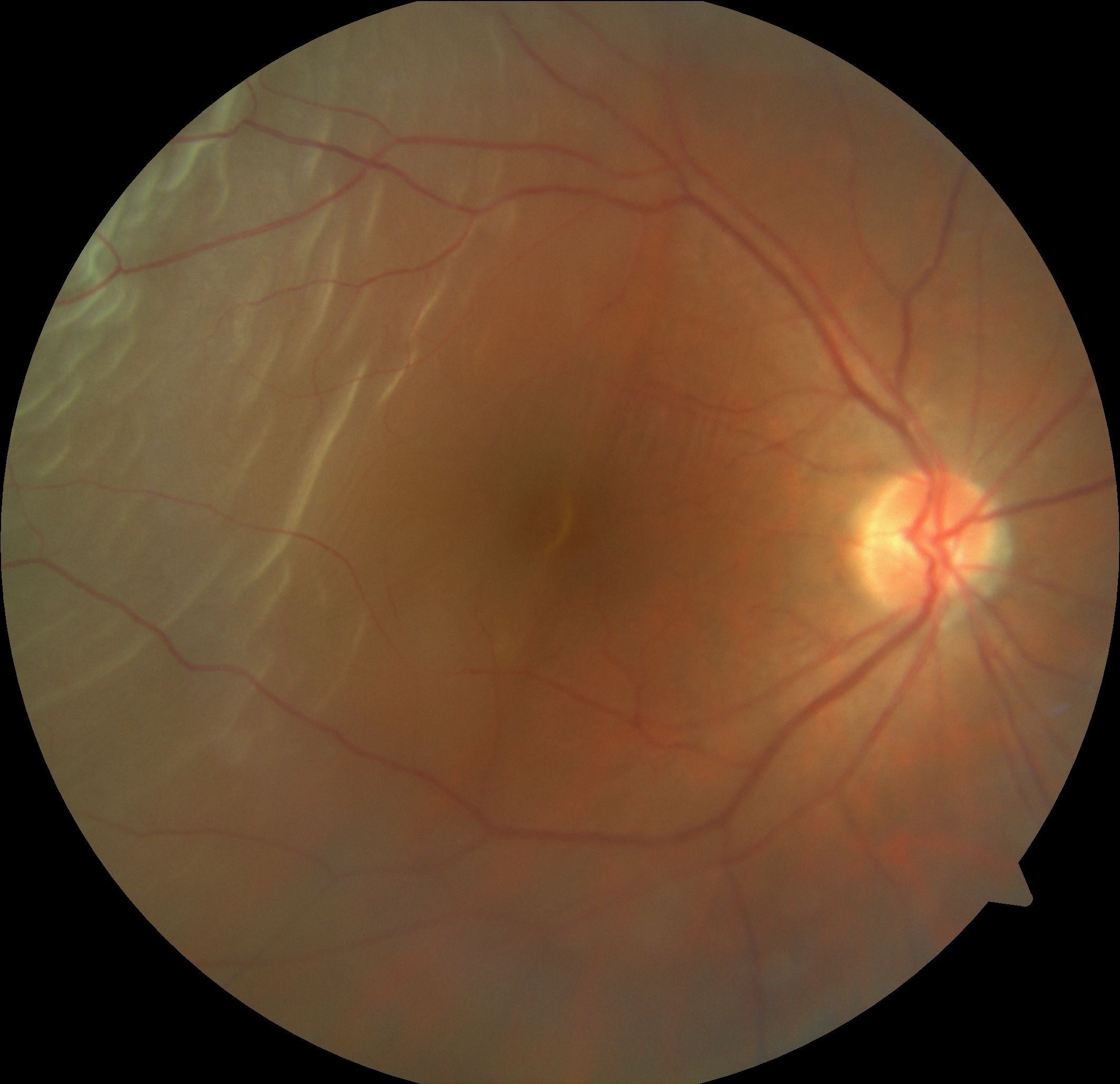

Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy OCT. Tractional retinal detachment shown on optical coherence tomography (OCT) of the right eye in a patient with proliferative diabetic retinopathy.

Courtesy of Chitaranjan Mishra, DNB, FICO, MRCS ED (Ophtha), Aravind Eye Hospital, Madurai, Tamil Nadu, India, 625020.

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Mahabadi N, Al Khalili Y. Neuroanatomy, Retina. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31424894]

Mishra C, Tripathy K. Retinal Traction Detachment. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32644378]

Shukla UV, Gupta A, Tripathy K. Exudative Retinal Detachment. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 36944005]

Rasouli M, Steed SM, Tennant MT, Rudnisky CJ, Hinz BJ, Greve MD, Somani R. The 1-year incidence of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment post 23-gauge pars plana vitrectomy. Canadian journal of ophthalmology. Journal canadien d'ophtalmologie. 2012 Jun:47(3):262-3. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2012.03.015. Epub 2012 May 10 [PubMed PMID: 22687303]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGupta OP, Benson WE. The risk of fellow eyes in patients with rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. Current opinion in ophthalmology. 2005 Jun:16(3):175-8 [PubMed PMID: 15870575]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJohnston T, Chandra A, Hewitt AW. Current Understanding of the Genetic Architecture of Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment. Ophthalmic genetics. 2016 Jun:37(2):121-9. doi: 10.3109/13816810.2015.1033557. Epub 2016 Jan 12 [PubMed PMID: 26757352]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGupta N, Tripathy K. Retinitis. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32809355]

Geetha R, Tripathy K. Chorioretinitis. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31869169]

Shukla M, Ahuja OP. A possible relationship between lattice and snail track degenerations of the retina. American journal of ophthalmology. 1981 Oct:92(4):482-5 [PubMed PMID: 7294110]

Byer NE. Lattice degeneration of the retina. Survey of ophthalmology. 1979 Jan-Feb:23(4):213-48 [PubMed PMID: 424991]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTripathy K, Chawla R, Sharma YR, Venkatesh P, Sagar P, Vohra R, Singh HI, Kumawat B, Bypareddy R. Prophylactic laser photocoagulation of fundal coloboma: does it really help? Acta ophthalmologica. 2016 Dec:94(8):e809-e810. doi: 10.1111/aos.12975. Epub 2016 Jan 29 [PubMed PMID: 26821601]

Shukla UV, Tripathy K. Diabetic Retinopathy. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32809640]

Roy S, Madan R, Gogia A, Tripathy K, Sharma D, Julka PK, Rath GK. Short course palliative radiotherapy in the management of choroidal metastasis: An effective technique since ages. Journal of the Egyptian National Cancer Institute. 2016 Mar:28(1):49-53. doi: 10.1016/j.jnci.2015.07.003. Epub 2015 Jul 31 [PubMed PMID: 26239538]

Koundanya VV, Tripathy K. Syphilis Ocular Manifestations. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32644383]

Paulbuddhe V, Addya S, Gurnani B, Singh D, Tripathy K, Chawla R. Sympathetic Ophthalmia: Where Do We Currently Stand on Treatment Strategies? Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, N.Z.). 2021:15():4201-4218. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S289688. Epub 2021 Oct 20 [PubMed PMID: 34707340]

Chawla R, Kapoor M, Mehta A, Tripathy K, Vohra R, Venkatesh P. Sympathetic Ophthalmia: Experience from a Tertiary Care Center in Northern India. Journal of ophthalmic & vision research. 2018 Oct-Dec:13(4):439-446. doi: 10.4103/jovr.jovr_86_17. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30479714]

Tripathy K, Mittal K, Chawla R. Sympathetic ophthalmia following a conjunctival flap procedure for corneal perforation. BMJ case reports. 2016 Mar 14:2016():. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2016-214344. Epub 2016 Mar 14 [PubMed PMID: 26976837]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGupta A, Tripathy K. Central Serous Chorioretinopathy. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32644399]

Venkatesh P, Chawla R, Tripathy K, Singh HI, Bypareddy R. Scleral resection in chronic central serous chorioretinopathy complicated by exudative retinal detachment. Eye and vision (London, England). 2016:3(1):23. doi: 10.1186/s40662-016-0055-5. Epub 2016 Sep 9 [PubMed PMID: 27617266]

Chawla R, Tripathy K, Meena S, Behera AK. Subretinal Hypopyon in Presumed Tubercular Uveitis: A Report of Two Cases. Middle East African journal of ophthalmology. 2018 Jul-Dec:25(3-4):163-166. doi: 10.4103/meajo.MEAJO_187_17. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30765956]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTripathy K, Chawla R. Choroidal tuberculoma. The National medical journal of India. 2016 Mar-Apr:29(2):106 [PubMed PMID: 27586221]

Tripathy K, Chawla R, Mutha V, Selvan H. Spontaneous suprachoroidal haemorrhage with exudative retinal detachment in pregnancy-induced hypertension. BMJ case reports. 2018 Mar 9:2018():. pii: bcr-2017-223907. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2017-223907. Epub 2018 Mar 9 [PubMed PMID: 29523618]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTripathy K, Chawla R. Bilateral exudative retinal detachment with choroidopathy in malignant hypertension. The National medical journal of India. 2015 Sep-Oct:28(5):261 [PubMed PMID: 27132968]

Bergstrom R, Tripathy K. Acute Retinal Necrosis. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29262034]

Gupta A, Paulbuddhe VS, Shukla UV, Tripathy K. Exudative Retinitis (Coats Disease). StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32809517]

Mitry D, Charteris DG, Fleck BW, Campbell H, Singh J. The epidemiology of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment: geographical variation and clinical associations. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2010 Jun:94(6):678-84. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2009.157727. Epub 2009 Jun 9 [PubMed PMID: 19515646]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMitry D, Tuft S, McLeod D, Charteris DG. Laterality and gender imbalances in retinal detachment. Graefe's archive for clinical and experimental ophthalmology = Albrecht von Graefes Archiv fur klinische und experimentelle Ophthalmologie. 2011 Jul:249(7):1109-10. doi: 10.1007/s00417-010-1529-0. Epub 2010 Oct 1 [PubMed PMID: 20886223]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChandra A, Banerjee P, Davis D, Charteris D. Ethnic variation in rhegmatogenous retinal detachments. Eye (London, England). 2015 Jun:29(6):803-7. doi: 10.1038/eye.2015.43. Epub 2015 Mar 27 [PubMed PMID: 25853394]

Rosman M, Wong TY, Ong SG, Ang CL. Retinal detachment in Chinese, Malay and Indian residents in Singapore: a comparative study on risk factors, clinical presentation and surgical outcomes. International ophthalmology. 2001:24(2):101-6 [PubMed PMID: 12201344]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSultan ZN, Agorogiannis EI, Iannetta D, Steel D, Sandinha T. Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment: a review of current practice in diagnosis and management. BMJ open ophthalmology. 2020:5(1):e000474. doi: 10.1136/bmjophth-2020-000474. Epub 2020 Oct 9 [PubMed PMID: 33083551]

Ahmed F, Tripathy K. Posterior Vitreous Detachment. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 33085420]

Iyer SSR, Regan KA, Burnham JM, Chen CJ. Surgical management of diabetic tractional retinal detachments. Survey of ophthalmology. 2019 Nov-Dec:64(6):780-809. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2019.04.008. Epub 2019 May 9 [PubMed PMID: 31077688]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSisk RA. Intraoperative Drainage of a Bullous Serous Pigment Epithelial Detachment. Ophthalmic surgery, lasers & imaging retina. 2019 Aug 1:50(8):510-513. doi: 10.3928/23258160-20190806-06. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31415698]

Hollands H, Johnson D, Brox AC, Almeida D, Simel DL, Sharma S. Acute-onset floaters and flashes: is this patient at risk for retinal detachment? JAMA. 2009 Nov 25:302(20):2243-9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1714. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19934426]

Broadway DC. How to test for a relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD). Community eye health. 2016:29(96):68-69 [PubMed PMID: 28381906]

Simakurthy S, Tripathy K. Marcus Gunn Pupil. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32491607]

D'Amico DJ. Clinical practice. Primary retinal detachment. The New England journal of medicine. 2008 Nov 27:359(22):2346-54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0804591. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19038880]

Tran KD, Schwartz SG, Smiddy WE, Flynn HW Jr. The Role of Scleral Depression in Modern Clinical Practice. American journal of ophthalmology. 2018 Nov:195():xviii-xix. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2018.08.017. Epub 2018 Sep 26 [PubMed PMID: 30268376]

Lahham S, Shniter I, Thompson M, Le D, Chadha T, Mailhot T, Kang TL, Chiem A, Tseeng S, Fox JC. Point-of-Care Ultrasonography in the Diagnosis of Retinal Detachment, Vitreous Hemorrhage, and Vitreous Detachment in the Emergency Department. JAMA network open. 2019 Apr 5:2(4):e192162. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.2162. Epub 2019 Apr 5 [PubMed PMID: 30977855]

Hallinan JT, Pillay P, Koh LH, Goh KY, Yu WY. Eye Globe Abnormalities on MR and CT in Adults: An Anatomical Approach. Korean journal of radiology. 2016 Sep-Oct:17(5):664-73. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2016.17.5.664. Epub 2016 Aug 23 [PubMed PMID: 27587955]

Gottlieb M, Holladay D, Peksa GD. Point-of-Care Ocular Ultrasound for the Diagnosis of Retinal Detachment: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Academic emergency medicine : official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. 2019 Aug:26(8):931-939. doi: 10.1111/acem.13682. Epub 2019 Feb 5 [PubMed PMID: 30636351]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceForte R, Pascotto F, de Crecchio G. Visualization of vitreomacular tractions with en face optical coherence tomography. Eye (London, England). 2007 Nov:21(11):1391-4 [PubMed PMID: 16751756]

Lincoff H, Gieser R. Finding the retinal hole. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 1971 May:85(5):565-9 [PubMed PMID: 5087597]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceElhusseiny AM, Yannuzzi NA, Smiddy WE. Cost Analysis of Pneumatic Retinopexy versus Pars Plana Vitrectomy for Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment. Ophthalmology. Retina. 2019 Nov:3(11):956-961. doi: 10.1016/j.oret.2019.06.003. Epub 2019 Jun 12 [PubMed PMID: 31416765]

Hoerauf H, Heimann H, Hansen L, Laqua H. [Scleral buckling surgery and pneumatic retinopexy. Techniques, indications and results]. Der Ophthalmologe : Zeitschrift der Deutschen Ophthalmologischen Gesellschaft. 2008 Jan:105(1):7-18. doi: 10.1007/s00347-007-1673-z. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18210120]

Ahmadieh H, Moradian S, Faghihi H, Parvaresh MM, Ghanbari H, Mehryar M, Heidari E, Behboudi H, Banaee T, Golestan B, Pseudophakic and Aphakic Retinal Detachment (PARD) Study Group. Anatomic and visual outcomes of scleral buckling versus primary vitrectomy in pseudophakic and aphakic retinal detachment: six-month follow-up results of a single operation--report no. 1. Ophthalmology. 2005 Aug:112(8):1421-9 [PubMed PMID: 15961159]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceStangos AN, Petropoulos IK, Brozou CG, Kapetanios AD, Whatham A, Pournaras CJ. Pars-plana vitrectomy alone vs vitrectomy with scleral buckling for primary rhegmatogenous pseudophakic retinal detachment. American journal of ophthalmology. 2004 Dec:138(6):952-8 [PubMed PMID: 15629285]

Ross WH, Lavina A. Pneumatic retinopexy, scleral buckling, and vitrectomy surgery in the management of pseudophakic retinal detachments. Canadian journal of ophthalmology. Journal canadien d'ophtalmologie. 2008 Feb:43(1):65-72. doi: 10.3129/i07-196. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18204500]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSchwartz SG, Flynn HW. Pars plana vitrectomy for primary rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, N.Z.). 2008 Mar:2(1):57-63 [PubMed PMID: 19668388]

Kohli P,Tripathy K, Agents for Vitreous Tamponade StatPearls. 2022 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 35593827]

Stewart MW, Browning DJ, Landers MB. Current management of diabetic tractional retinal detachments. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2018 Dec:66(12):1751-1762. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1217_18. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30451175]

Ip M, Garza-Karren C, Duker JS, Reichel E, Swartz JC, Amirikia A, Puliafito CA. Differentiation of degenerative retinoschisis from retinal detachment using optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmology. 1999 Mar:106(3):600-5 [PubMed PMID: 10080221]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMuth CC. Sudden Vision Loss. JAMA. 2017 Aug 8:318(6):584. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.7950. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28787508]

Hsu YJ, Hsieh YT, Yeh PT, Huang JY, Yang CM. Combined Tractional and Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment in Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy in the Anti-VEGF Era. Journal of ophthalmology. 2014:2014():917375. doi: 10.1155/2014/917375. Epub 2014 Jun 25 [PubMed PMID: 25061523]

Semidey VA,Al Taisan AA,Schatz P,Taskintuna I,Mura M, Surgical Management of Hemorrhagic Retinal Detachment Secondary to Peripheral Exudative Hemorrhagic Chorioretinopathy. Middle East African journal of ophthalmology. 2021 Jan-Mar; [PubMed PMID: 34321823]

Wykoff CC, Smiddy WE, Mathen T, Schwartz SG, Flynn HW Jr, Shi W. Fovea-sparing retinal detachments: time to surgery and visual outcomes. American journal of ophthalmology. 2010 Aug:150(2):205-210.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2010.03.002. Epub 2010 Jun 11 [PubMed PMID: 20541738]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLee IT, Lampen SIR, Wong TP, Major JC Jr, Wykoff CC. Fovea-sparing rhegmatogenous retinal detachments: impact of clinical factors including time to surgery on visual and anatomic outcomes. Graefe's archive for clinical and experimental ophthalmology = Albrecht von Graefes Archiv fur klinische und experimentelle Ophthalmologie. 2019 May:257(5):883-889. doi: 10.1007/s00417-018-04236-4. Epub 2019 Jan 11 [PubMed PMID: 30635720]

Steel D. Retinal detachment. BMJ clinical evidence. 2014 Mar 3:2014():. pii: 0710. Epub 2014 Mar 3 [PubMed PMID: 24807890]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGrabowska A, Neffendorf JE, Yorston D, Williamson TH. Urgency of retinal detachment repair: is it time to re-think our priorities? Eye (London, England). 2021 Apr:35(4):1035-1036. doi: 10.1038/s41433-020-01154-w. Epub 2020 Sep 1 [PubMed PMID: 32873942]

Christensen U, Villumsen J. Prognosis of pseudophakic retinal detachment. Journal of cataract and refractive surgery. 2005 Feb:31(2):354-8 [PubMed PMID: 15767158]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSobol WM, Blodi CF, Folk JC, Weingeist TA. Long-term visual outcome in patients with optic nerve pit and serous retinal detachment of the macula. Ophthalmology. 1990 Nov:97(11):1539-42 [PubMed PMID: 2255526]

Piccolino FC, de la Longrais RR, Ravera G, Eandi CM, Ventre L, Abdollahi A, Manea M. The foveal photoreceptor layer and visual acuity loss in central serous chorioretinopathy. American journal of ophthalmology. 2005 Jan:139(1):87-99 [PubMed PMID: 15652832]

Idrees S, Sridhar J, Kuriyan AE. Proliferative Vitreoretinopathy: A Review. International ophthalmology clinics. 2019 Winter:59(1):221-240. doi: 10.1097/IIO.0000000000000258. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30585928]

Sharma A, Grigoropoulos V, Williamson TH. Management of primary rhegmatogenous retinal detachment with inferior breaks. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2004 Nov:88(11):1372-5 [PubMed PMID: 15489475]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceJalali S. Retinal detachment. Community eye health. 2003:16(46):25-6 [PubMed PMID: 17491854]

Flaxel CJ, Adelman RA, Bailey ST, Fawzi A, Lim JI, Vemulakonda GA, Ying GS. Posterior Vitreous Detachment, Retinal Breaks, and Lattice Degeneration Preferred Practice Pattern®. Ophthalmology. 2020 Jan:127(1):P146-P181. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2019.09.027. Epub 2019 Sep 25 [PubMed PMID: 31757500]

Koçak N, Kaya M, Öztürk T, Bolluk V, Kaynak S. Demarcation Laser Photocoagulation for Subclinical Retinal Detachment: Can Progression to Retinal Detachment Be Prevented? Turkish journal of ophthalmology. 2019 Dec 31:49(6):342-346. doi: 10.4274/tjo.galenos.2019.22844. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31893590]

Uhumwangho OM,Jalali S, Chorioretinal coloboma in a paediatric population. Eye (London, England). 2014 Jun; [PubMed PMID: 24675580]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFan S, Lin D, Wu R, Wang Y. Efficacy of prophylactic laser retinopexy in acute retinal necrosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International ophthalmology. 2022 May:42(5):1651-1660. doi: 10.1007/s10792-021-02131-2. Epub 2022 Mar 21 [PubMed PMID: 35307785]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBshouti E, Hoban K, Affel E, Bourbonniere M, Line C, Murchison AP. Ocular emergencies in an ophthalmic emergency room. Insight (American Society of Ophthalmic Registered Nurses). 2014 Summer:39(3):18-21 [PubMed PMID: 25195337]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceEijk ES, Busschbach JJ, Timman R, Monteban HC, Vissers JM, van Meurs JC. What made you wait so long? Delays in presentation of retinal detachment: knowledge is related to an attached macula. Acta ophthalmologica. 2016 Aug:94(5):434-40. doi: 10.1111/aos.13016. Epub 2016 Mar 24 [PubMed PMID: 27008986]

Quinn SM, Qureshi F, Charles SJ. Assessment of delays in presentation of patients with retinal detachment to a tertiary referral centre. Ophthalmic & physiological optics : the journal of the British College of Ophthalmic Opticians (Optometrists). 2004 Mar:24(2):100-5 [PubMed PMID: 15005674]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence