Chronic Kidney Disease-Mineral Bone Disorder (CKD-MBD)

Chronic Kidney Disease-Mineral Bone Disorder (CKD-MBD)

Introduction

In 2005, Moe et al coined the term chronic kidney disease–mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD) to describe a complex clinical syndrome encompassing disorders of calcium, phosphate, parathyroid hormone (PTH), vitamin D, and fibroblast growth factor-23 (FGF23) metabolism. These disruptions lead to alterations in bone morphology (renal osteodystrophy), vascular calcification, and cardiovascular death in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD).[1] These abnormalities can potentially lead to high mortality rates, mainly from cardiovascular complications. Since the term CKD-MBD was introduced, various clinical guidelines have been developed, recommending specific laboratory targets and management options to improve the morbidity and mortality associated with this systemic syndrome. CKD-MBD can be assessed through histomorphometry of bone biopsy. Derangements in serum levels of calcium, phosphorus, PTH, and vitamin D, along with their effects on bone turnover, mineralization, and extraskeletal calcifications, are significant aspects of this syndrome. Although most features appear when the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) falls below 40 mL/min, some elements, such as loss of Klotho (a transmembrane protein), increased FGF23 secretion, decreased bone synthesis rates, and vascular calcification, often occur before abnormal biochemical markers manifest.[2][3] Compelling evidence indicates a causal relationship between these derangements and numerous adverse clinical outcomes, particularly increased fracture risk and cardiovascular mortality.

This activity highlights notable discoveries regarding the pathogenesis of CKD-MBD, including insights into the roles of FGF23, Klotho, Wnt inhibitors, and activin A. Management strategies for CKD-MBD primarily focus on preventing adverse effects associated with secondary hyperparathyroidism. Thus, management of secondary hyperparathyroidism is guided by established surrogate markers of deranged mineral bone metabolism, such as serum calcium, phosphate, PTH, and 25-hydroxyvitamin D.[4][5] Renal osteodystrophy, an aspect of CKD-MBD, represents alterations in bone morphology. Although bone biopsy is the gold standard for diagnosing and classifying it, this invasive procedure is rarely performed. Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) recommends monitoring the serial trend of biochemical markers for ongoing management of renal osteodystrophy. Furthermore, the 2017 update no longer advises performing a bone biopsy before initiating these medications.[5]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

CKD-MBD is a multifactorial condition characterized by biochemical, morphological, skeletal, and non-skeletal abnormalities involving various body systems. The key etiological factors contributing to its development are mentioned below.

Impaired kidney function: Impaired kidney function is a critical factor in the development of CKD-MBD, which occurs in patients with CKD. The kidneys maintain mineral and electrolyte homeostasis, including calcium and phosphate levels. As kidney function declines, this delicate balance is disrupted, contributing to the development of CKD-MBD.

Dysregulated calcium, phosphate, and vitamin D homeostasis: In CKD, reduced kidney function leads to impaired phosphate excretion and decreased synthesis of active vitamin D (calcitriol or 1,25 dihydroxy vitamin D), resulting in hyperphosphatemia and hypocalcemia. These imbalances contribute to adverse effects such as vascular calcification associated with CKD-MBD.

Abnormal PTH regulation: Impaired kidney function in CKD disrupts PTH regulation, resulting in secondary hyperparathyroidism. Elevated phosphate levels, low calcium levels, and inadequate vitamin D stimulate excessive PTH secretion, leading to bone resorption and calcium release, disrupting the calcium balance in the skeletal system. Secondary hyperparathyroidism is the predominant factor contributing to renal osteodystrophy.

Secondary Hyperparathyroidism

Secondary hyperparathyroidism is a significant manifestation of CKD-MBD, often diagnosed and monitored using PTH levels. This condition arises due to various events that initiate and maintain excess PTH secretion, resulting in the following effects:

- Phosphate retention

- Decreased free ionized calcium concentration

- Decreased calcitriol concentration

- Increased FGF23 concentration

- Reduced expression of calcium-sensing receptors (CaSRs), vitamin D receptors, and FGF receptors in the parathyroid glands [6]

Examining the alterations in their homeostasis during CKD provides insights into the importance of these factors in developing secondary hyperparathyroidism. An increase in PTH concentration typically occurs when the estimated GFR (eGFR) falls below 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. At that point, serum calcium and phosphate concentrations remain within the normal range until the eGFR decreases to approximately 20 mL/min/1.73 m2. However, the concentration of calcitriol begins to decline much earlier, occurring when the eGFR is less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 due to increased FGF23 concentration rather than kidney tissue loss.[7] Hyperphosphatemia also contributes to decreased calcitriol production by suppressing the 1-α-hydroxylase enzyme. This, in turn, leads to calcitriol deficiency and contributes to the development of hypocalcemia. These biochemical changes then stimulate the release of PTH and increase its concentration through various pathways described below:

Phosphate retention: Serum hyperphosphatemia can stimulate PTH secretion through various mechanisms. Typically, this occurs either by directly increasing PTH messenger ribonucleic acid levels or indirectly by reducing calcium and calcitriol levels, leading to an elevation in PTH levels.[8][9]

Calcium: Calcium is crucial in regulating PTH levels through the CaSR. A decrease in serum calcium levels triggers the parathyroid glands to secrete PTH, highlighting the established relationship between calcium and PTH levels.

Calcitriol: The role of calcitriol is crucial in maintaining serum calcium levels and regulating PTH secretion. Calcitriol and PTH work together to increase serum calcium levels. When calcitriol levels decrease, secondary hyperparathyroidism can develop due to reduced calcium absorption in the intestine, leading to a reflex increase in PTH secretion. Additionally, calcitriol is necessary to suppress PTH secretion by the parathyroid glands.

Fibroblast growth factor-23: FGF23 decreases phosphate levels in the body. In CKD, the first biochemical abnormality noted is decreased α-Klotho (referred to as Klotho), a transmembrane receptor primarily found in the proximal and distal renal tubules. Klotho is a cofactor for FGF23, and reduced levels lead to increased FGF23 due to the lack of negative feedback. This increase in FGF23 results in decreased urine phosphorus reabsorption through the sodium-phosphorus type II cotransporter. Additionally, FGF23 downregulates the 1-α-hydroxylase enzyme, which decreases activated vitamin D.[10][11]

Phosphate Retention

Phosphate retention in CKD involves several theoretical explanations, and a notable hypothesis being the "trade-off" hypothesis. This hypothesis posits that hyperphosphatemia contributes to secondary hyperparathyroidism by lowering ionized calcium concentration and inhibiting calcitriol synthesis.[12] The resulting excess of PTH promotes renal phosphate excretion by reducing proximal tubular phosphate reabsorption. This action increases bone resorption to elevate serum calcium levels and stimulates kidney synthesis of calcitriol, which enhances intestinal calcium absorption.[13] This hypothesis suggests that the initially adaptive increase in PTH is beneficial, resulting in increased phosphate excretion, lowered plasma phosphate concentration, and reduced phosphate reabsorption. Additionally, it tends to correct calcitriol deficiency and hypocalcemia. However, the long-term effect of excess PTH becomes maladaptive over time. Moreover, in advanced CKD stages, the compensatory rise in PTH becomes insufficient, leading to continued elevation of phosphate concentrations.[14][15]

The pathological effects of hyperphosphatemia in patients with CKD-MBD include the following:

- FGF23 secretion, which suppresses PTH secretion [16]

- Osteoblastic transformation of smooth muscle cells in the vasculature, contributing to cardiovascular calcification and arterial stiffness [17]

Decreased Calcitriol Activity

Plasma calcitriol concentration usually decreases when the eGFR falls below 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. In the earlier stages of the disease, this decrease is primarily due to the increased FGF23 concentration. However, in advanced CKD, the reduction in functioning kidney mass and hyperphosphatemia also contribute to decreased calcitriol formation. FGF23 suppresses the activity of 1-α-hydroxylase and stimulates the 24-hydroxylase enzyme, leading to decreased synthesis of calcitriol.[18] Calcitriol is an essential link among various CKD-MBD, including phosphate, calcium, PTH, FGF23, and Klotho. Decreased calcitriol activity can influence PTH in the following ways:

- Reduced intestinal absorption of calcium

- Decline in the number of vitamin D receptors in the parathyroid cells

- Removal of the inhibitory effect on the parathyroid gland [19]

Calcium Balance Disorders

Calcium plays a pivotal role in regulating PTH secretion, with even minor fluctuations in its serum levels detected by the CaSR abundant in parathyroid glands.[20] The CaSR tightly regulates PTH secretion in response to changes in ionized calcium concentrations, with PTH secretion inversely related to serum calcium levels. Both hypocalcemia and hypercalcemia contribute to increased mortality among CKD patients.[21] Hypocalcemia is prevalent in CKD and leads to excessive PTH secretion (as sensed by the CaSR), resulting in abnormal bone remodeling; conversely, hypercalcemia is linked to extraskeletal calcification.

Fibroblast Growth Factor-23

FGF23 plays a central role in regulating PTH levels, and its levels rise even before PTH elevation.[6] FGF23 is secreted in response to calcitriol, dietary phosphate load, calcium, and PTH.[22] Patients with CKD may also have an increased FGF23 concentration due to decreased clearance.[23] FGF23 maintains normal serum phosphate levels by decreasing renal phosphate reabsorption through the sodium/phosphorus cotransporter type II and inhibiting intestinal phosphate absorption via decreased calcitriol production. Moreover, FGF23 decreases calcitriol synthesis by inhibiting the expression of 1-α-hydroxylase in the proximal tubule.[24] These actions collectively result in increased urinary phosphate excretion and decreased intestinal phosphate absorption, leading to lower serum phosphate levels. Additionally, FGF23 suppresses PTH secretion by the parathyroid gland.[25] Klotho, a transmembrane protein expressed in proximal and distal renal tubules, is crucial in activating FGF23 receptors.[26] Klotho may also have regulatory effects on bone formation and bone mass. A feedback relationship exists between FGF23 and Klotho, where Klotho deficiency leads to increased FGF23 levels, while elevated FGF23 concentration exacerbates Klotho deficiency due to low 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D levels.[27]

Epidemiology

CKD-MBD presents with a range of manifestations, and its prevalence varies depending on the specific aspects of the disorder. For example, vascular calcification is more common among patients on dialysis patients, with arterial morphometry revealing increased medial thickening.[28] Vascular calcification begins early and becomes more prevalent as GFR declines, with approximately 80% of dialysis patients experiencing coronary artery calcification.[29][30] Studies have reported varying prevalence rates for CKD-MBD; for instance, recent data based on the Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (KDOQI) suggest a prevalence of 55%, while the KDIGO guidelines estimate it at 86%.[31]

In the last few decades, the trend has shifted from hyperparathyroidism-induced high bone turnover diseases to adynamic bone disease.[32] Several factors are hypothesized to contribute to this shift, such as the overuse of vitamin D analogs, which suppress PTH.[33] Similarly, calcium-containing phosphate binders exert a comparable effect on PTH levels. Patients on maintenance dialysis with diabetes also tend to have lower PTH levels than those without diabetes, resulting in a higher incidence of low bone turnover.[34] Another contributing factor to the rise in adynamic bone disease is the decline of osteomalacia, facilitated by the introduction of non-aluminum-based phosphate binders and more effective methods for treating water used in preparing the dialysate.[35][36]

Pathophysiology

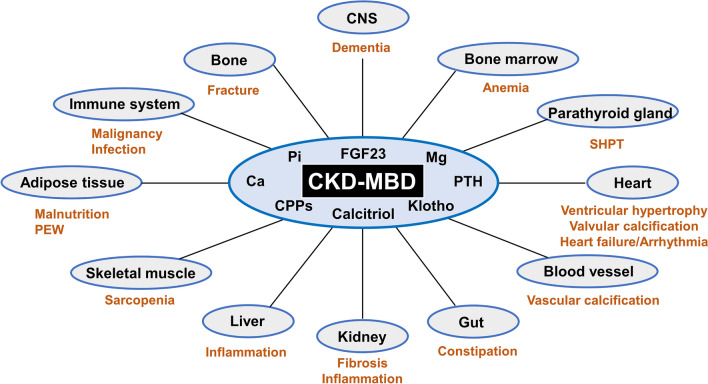

The pathophysiology of CKD-MBD can be divided into different components based on the condition's varied presentations. This disease can be categorized into skeletal and extraskeletal manifestations (see Image. Systemic Impact of Chronic Kidney Disease–Mineral Bone Disorder [CKD-MBD]).

Skeletal Abnormalities in CKD-MBD (Renal Osteodystrophy)

Renal osteodystrophy, the skeletal manifestation of CKD-MBD, is histologically classified into high or low bone turnover states. A third category is mixed uremic osteodystrophy, which exhibits high and low bone turnover and abnormal mineralization characteristics. Mixed uremic osteodystrophy encompasses features of high-turnover osteitis fibrosa cystica and low-turnover mineralization defects, as observed in osteomalacia.[9] Along with bone disorders, muscle weakness, myopathy, and calcifications are recognized components of CKD-MBD.[37]

High bone turnover: High bone turnover states are characterized by increased bone resorption and formation rates. Elevated PTH levels are significant in the pathogenesis of these states, which can manifest as primary, secondary, or tertiary hyperparathyroidism. An example of tertiary hyperparathyroidism is seen in parathyroid gland adenomas autonomously secreting PTH, leading to a state of high bone turnover.[38] End-stage high-turnover bone disease may rarely result in osteitis fibrosa cystica, a condition characterized by increased bone turnover due to secondary hyperparathyroidism. This increased turnover leads to distinctive hemosiderin deposits known as "brown tumors." Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Osteitis Fibrosa Cystica," for further information.[39]

Low bone turnover: Low bone turnover states primarily include osteomalacia and adynamic bone disease, both seen in patients with end-stage renal disease. The critical factors that play a role in the pathogenesis are the following:

- Osteomalacia: Heavy metal intoxication, mainly aluminum, can lead to dysfunction of osteoblasts and osteoclasts. Dysfunctional osteoblasts lead to defective bone mineralization and an accumulation of excess bone matrix. Other metals, such as iron and cadmium, have also been implicated. However, this form of osteomalacia has become less prevalent in recent decades.

- Adynamic bone disease: Adynamic bone disease primarily develops due to suppressed PTH levels, resulting in low bone turnover and insufficient bone mineralization without excess osteoid accumulation seen in osteomalacia. This condition has become increasingly prevalent over time, with skeletal resistance to PTH being a key contributing factor.[40] Factors contributing to the development of adynamic bone disease include:

- Calcium and vitamin D: Aggressive treatment with these compounds in patients with CKD causes chronic PTH suppression.[41][42]

- Activated vitamin D (calcitriol): Supplementation with calcitriol can reduce bone turnover, as indicated by bone turnover markers; however, the mechanism by which this occurs, whether through decreased PTH levels, remains unclear.[43]

- Continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis: This condition results in a significant calcium influx into the body through the dialysate.

- Diabetes mellitus: Evidence suggests that elevated glucose levels and reduced insulin levels are associated with suppression of PTH secretion.[43][44]

- Other factors: Additional factors, such as interleukin-4 and deficiency of osteogenic protein-1, also have secondary roles in the pathogenesis of adynamic bone disease.[38]

Extraskeletal Manifestations

Although skeletal manifestations (renal osteodystrophy) have received the most attention regarding the effects of CKD and CKD-MBD, evidence is growing of the systemic vast impact, especially on cardiovascular health. Other body systems affected include anemia, constipation, liver inflammation, malignancy, infection, malnutrition, and dementia.

Vascular calcification: Vascular calcification in CKD-MBD has been extensively studied due to its association with morbidity and mortality. Previously, vascular calcification was considered a passive consequence of degenerative aging, but it is now known to be an actively regulated process similar to bone formation. The process involves complex interactions among vascular smooth muscle cells, the extracellular matrix, and calciprotein particles (CPPs). These particles, formed in high calcium and phosphate conditions, contain calcium, phosphate, fetuin-A, and other proteins. CPPs induce inflammatory responses and can cause smooth muscle cell apoptosis and extracellular matrix calcification.[11][45] In the uremic milieu, characteristic of CKD, calcification promoters such as calcium and phosphate increase, whereas calcification inhibitors such as fetuin-A and pyrophosphate decrease.[46] Additionally, decreased calcitriol levels are associated with endothelial dysfunction and increased vascular stiffness.[47]

Cardiac abnormalities: Cardiac abnormalities are prevalent in CKD-MBD and contribute significantly to morbidity and mortality. Elevated levels of PTH and FGF23 are associated with cardiovascular events. FGF23 activation of distal tubular sodium-chloride cotransporters increases the risk of volume overload and is linked to conditions such as atrial fibrillation and cardiomyocyte hypertrophy.[47] Reduced levels of Klotho, a protein decreased in CKD, are thought to have cardioprotective effects. Animal studies with Klotho knockout mice have shown left ventricular hypertrophy and cardiac fibrosis.[48] Valvular disease can be attributed to osteoblast-like cells in cardiac valves, which produce bone-related peptides, contributing to extracellular matrix calcification.[47]

Neurological events: Neurological events such as dementia, small cerebral vessel disease, and cognitive decline have been linked to elevated levels of FGF23 in data from the Framingham Heart Study.[49][37] Another large prospective study involving patients on hemodialysis revealed that hyperphosphatemia was associated with brain hemorrhage, while hypophosphatemia was linked to brain ischemic events.[50] Another large longitudinal study found that high PTH levels were associated with a higher risk of hemorrhagic stroke and myocardial infarction. This study also revealed that hyperphosphatemia and hypercalcemia were linked to an increased risk of brain hemorrhage. This is thought to be due to vascular calcification (for hypercalcemia), increased vascular smooth muscle disruption through matrix metalloproteinases II and IX, and cathepsin S in the case of hyperphosphatemia.[51]

Gastrointestinal effects: Gastrointestinal effects associated with CKD-MBD include constipation, liver inflammation, and alterations in the intestinal microbiome.[11] Hyperphosphatemia, dietary restrictions, phosphate binders, and uremic toxins can impact natural intestinal bacteria. Traditional calcium-containing phosphate binders and anion-exchange binders might influence the microbiome, with newer iron-containing binders showing potentially lesser effects, although current data are inconclusive.[52][53][54]

Infections: Infections are the second-leading cause of death in patients on hemodialysis, and evidence indicates a relationship between CKD-MBD and infection-related mortality. Elevated levels of PTH and FGF23 can hinder leukocyte recruitment and impair the host immune response. Hypercalcemia is also associated with all-cause mortality and infection-related deaths among patients on hemodialysis. This effect is particularly noticeable in younger patients and those with hypoalbuminemia, potentially due to decreased leukocyte function or elevated levels of FGF23 and CPPS.[55] This correlation is further supported by studies demonstrating a reduction in severe sepsis among patients on calcium channel blockers.[56][57]

Malnutrition: Malnutrition is prevalent in patients with end-stage renal disease due to factors such as uremic toxins, chronic inflammation, protein loss during dialysis, and dietary constraints. Studies have revealed that elevated FGF23 levels correlate with increased inflammatory markers and C-reactive protein levels. Animal models have also demonstrated that elevated PTH can convert white adipose tissue to brown, contributing to cachexia.[11] In addition, data from the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study have linked elevated PTH levels with greater weight loss, suggesting an independent effect beyond appetite measures.[58]

History and Physical

Patients with CKD-MBD exhibit symptoms based on prevalent metabolic abnormalities and the associated bone disease. Initially, hyperparathyroidism may be asymptomatic, but over time, patients may experience prominent symptoms such as bone pain and proximal myopathy. Due to the gradual onset of symptoms, they are often underreported until appropriate treatment is initiated, providing relief from pain. While fractures are uncommon in parathyroid disease, adolescents and children may experience rapid development of significant bone deformities due to metaphyseal erosion of long bones. Hyperparathyroidism can also diminish the efficacy of erythropoietin therapy.

The syndrome of aluminum-induced osteomalacia manifests as generalized bone pain, frequent fractures, and proximal myopathy. The involvement of proximal muscles and the axial skeleton suggests aluminum toxicity and osteomalacia.[59] Excess total body aluminum can lead to hypochromic anemia and dementia. However, this presentation is now less common due to increased awareness of aluminum toxicity. A mixed form of aluminum and parathyroid disease, as well as milder forms of aluminum-related bone disease, are also recognized. Patients with these forms of the disease tend to have fewer symptoms. Aluminum tends to accumulate more rapidly in the bones of children and younger patients compared to older patients, and it deposits more readily in patients with type 1 diabetes.

Low turnover states, which lead to defective mineralization and an inability to repair ongoing damage, are more commonly symptomatic. With increasing awareness and the development of therapies to suppress hyperparathyroidism, adynamic bone disease has emerged as a result. Bone pain is the predominant symptom in patients with adynamic bone disease.[60] These patients also have a higher risk of fractures, and growth impairment may occur in children. The increased fracture incidence in these patients can also be attributed to the poor structural integrity of bones associated with adynamic bone disease. However, maintaining higher plasma calcium concentrations to suppress the parathyroid gland increases the risk of vascular calcification.

Patients with adynamic bone disease often have an overly suppressed PTH level, coupled with an inability to buffer calcium onto the bone, which leads to hypercalcemia.[61] Vascular calcifications are a crucial complication that can result in site-specific manifestations. Calcifications in blood vessels can increase wall stiffness and pulse pressure, contributing to chronic hypertension, which can lead to a higher incidence of cardiovascular events and strokes, a significant cause of mortality in patients with CKD.[62] Moreover, hypercalcemia, hyperphosphatemia, and elevated PTH levels are also associated with calciphylaxis. Please see Statpearls' companion resource, "Calciphylaxis," for further information.[63]

In children with CKD, symptoms of renal osteodystrophy include fractures, bone pain, avascular necrosis, growth failure, and skeletal deformities.[64] Rare reports exist of patients developing intracranial hypertension due to jugular foramen stenosis caused by renal osteodystrophy.[65] Findings of renal osteodystrophy caused by secondary hyperparathyroidism in cranial bones include osteosclerosis, osteomalacia, erosion of the cortical bone, brown tumors, and resorption of the lamina dura. One of the most severe osseous complications is uremic leontiasis ossea, characterized by excessive thickening of the skull and facial bones, with only a few cases reported in the literature.[66]

Evaluation

Diagnostic Approaches for CKD-MBD

As most patients with CKD-MBD are asymptomatic at the outset of the disorder, an investigation should be performed whenever clinical suspicion is high. Although a bone biopsy is the gold standard for diagnosis, it is not always feasible due to its invasiveness. However, blood tests for markers of bone metabolism, combined with radiological imaging, can help narrow down the differential diagnosis in patients mentioned below.

- PTH plays a significant role in the pathogenesis of CKD-MBD and can differentiate between high and low bone turnover states.[38] The diagnostic cutoff level for PTH varies based on whether the patient is on dialysis.

- If PTH levels are elevated, the next reasonable step is to assess vitamin D levels in the blood.

- Serum calcium and phosphate levels are crucial in establishing the diagnosis of CKD-MBD.

- Bone-specific alkaline phosphatase (bsALP) indicates osteoblastic activity. Low levels of bsALP may suggest a low bone turnover disease, aiding in diagnosis.

- Osteocalcin and propeptide of type I collagen are bone formation markers found in the blood of patients with renal osteodystrophy. However, due to a poor association with the disease in study results, they are not commonly used in clinical practice.[8]

Radiological studies are crucial in characterizing bone disease associated with CKD-MBD. Hyperparathyroidism-related osteitis fibrosa manifests as skeletal changes indicative of underlying renal osteodystrophy. Subperiosteal resorption, endosteal resorption, and osteolysis may appear in the skull, clavicle, or distal phalanges. Dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scans are utilized to measure bone mineral density, although their definitive validation remains uncertain.[67] The 2017 KDIGO guidance recommended considering bone mineral density testing to evaluate fracture risk in CKD patients with osteoporosis risk factors, suggesting therapy adjustments based on the results.

The definitive test for diagnosing CKD-MBD is a bone biopsy followed by double tetracycline labeling, which accurately identifies the patient's histological pattern of bone disease.[41] Another emerging marker, FGF23, has gained attention recently. Despite its well-established clinical effects, FGF23 is seldom used as a biomarker due to challenges such as instability (ex vivo degradation), diurnal variability, high cost, and lack of precision.[68]

Monitoring Parameters

Patients with secondary hyperparathyroidism are regularly monitored by measuring serum levels of calcium, phosphate, and PTH.[5] Some healthcare providers also include bsALP as part of their monitoring protocol to assess the need for parathyroidectomy. However, insufficient evidence prevails to fully support its utility. Although both PTH and bsALP can individually predict high-turnover bone disease, the combined use of these tests offers minimal additional predictive value.[69] Standard frequency of monitoring does not exist for CKD-MBD. Typically, measuring serum phosphate and calcium levels every 1 to 3 months and PTH every 3 to 6 months is deemed appropriate.[5] However, these intervals may be adjusted as needed based on changes in therapy that could impact these levels. Many clinicians opt to measure vitamin D concentrations on an annual basis.

Treatment / Management

The treatment for patients with CKD-MBD varies according to the prevailing metabolic abnormality, the severity of the underlying kidney impairment, and the characteristic bone disease. Management of this condition revolves around strict control of phosphate, calcium, vitamin D, and PTH levels.

Treatment for Adult Nondialysis Patients

All patients with CKD with an eGFR of less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 are at risk of developing secondary hyperparathyroidism. Therefore, monitoring PTH, calcium, phosphate, 25-hydroxy vitamin D, and bsALP (where available) is recommended. Serial assessment of these biochemical markers guides treatment. The components of a management plan for patients who are not on dialysis include the following:

Phosphate: Maintaining serum phosphate levels below 5.5 mg/dL is crucial to reduce elevated PTH levels. Patients are strongly advised to follow a phosphorus-restricted diet, with preference given to vegetarian meals due to the lower bioavailability of phosphorus in vegetarian proteins.[70] For patients with persistently high serum phosphate levels despite dietary restrictions, phosphate binders taken with meals are recommended. Non-calcium-containing binders such as sevelamer and lanthanum are preferred as they do not affect calcium levels.[71] However, in cases of hypocalcemia requiring calcium supplementation, clinicians may prescribe calcium-containing binders such as calcium acetate and calcium carbonate. In addition, it is important to ensure that elemental calcium intake remains below 2 g/d in these situations.[72](A1)

Calcium: Patients with asymptomatic and mild hypocalcemia (above 7.5 mg/dL with normal albumin levels) typically do not require treatment with calcium or vitamin D derivatives such as synthetic vitamin D analogs or calcitriol. These treatments can potentially cause hypercalcemia or positive calcium balance. Addressing vitamin D deficiency may indirectly correct mild hypocalcemia. Another concern with the oral administration of calcium and vitamin D analogs is the heightened risk of vascular calcification. The recommended daily dietary calcium intake is approximately 1000 mg, and prescribing 1500 mg of elemental calcium daily (as calcium carbonate 1250 mg 3 times a day) significantly increases calcium intake by approximately 2.5-fold. Coupled with reduced calcium excretion in CKD, this creates a positive calcium balance, which then promotes vascular calcification and other sequelae.[73](A1)

Vitamin D: Vitamin D deficiency is prevalent among CKD patients and may present as an initial lab abnormality. This deficiency correlates with hyperparathyroidism and can exacerbate hypocalcemia. CKD patients with vitamin D deficiency are typically supplemented with cholecalciferol or ergocalciferol, except in the following cases:

- Patients with hyperphosphatemia, until phosphate levels are under control

- Patients with hypercalcemia

Activated vitamin D (calcitriol) is reserved for patients with advancing hyperparathyroidism. The effectiveness of vitamin D supplementation remains uncertain in patients with CKD.[74] A meta-analysis indicated that vitamin D supplementation can enhance vitamin D and PTH levels, potentially reducing the occurrence of hyperphosphatemia and hypercalcemia.[75](A1)

Hyperparathyroidism: Patients with CKD and persistent or progressive hyperparathyroidism should undergo treatment targeting modifiable risk factors such as vitamin D deficiency, hyperphosphatemia, and excessive phosphate intake. If these measures fail to decrease PTH levels, the use of calcitriol can be considered. Calcitriol and synthetic vitamin D analogs are known to reduce or stabilize PTH levels (sometimes with a risk of inducing hypercalcemia).[76][77] However, the decision to initiate calcitriol or synthetic vitamin D analogs varies among healthcare providers; commonly, treatment initiation occurs when PTH levels exceed 2 to 3 times the upper limit (eg, 150-200 pg/mL if the upper limit is 65 pg/mL). The recommended starting dosage is 0.25 μg administered thrice weekly, with titration to achieve a target PTH level below 150 pg/mL.(A1)

Calcitriol is contraindicated when phosphate levels exceed the normal range or if free calcium concentration is 9.5 mg/dL (2.37 mmol/L) or higher. Various oral agents such as calcitriol, alfacalcidol, paricalcitol, or doxercalciferol can be considered as comparative efficacy has not been firmly established in nondialysis patients.[78] Another class of drugs includes calcimimetics, such as cinacalcet. However, this class is not recommended for suppressing PTH among patients not on dialysis. Several adverse effects complicate its use in nondialysis patients, including hypocalcemia, increased calciuria, and hyperphosphatemia.[79] The KDIGO 2017 guidance does not offer specific recommendations regarding cinacalcet. Previous KDIGO guidelines advised against using cinacalcet due to the lack of evidence in predialysis patients with CKD.[80](A1)

Treatment for Adult Dialysis Patients

Patients on dialysis have the following recommended targets of therapy:

- Phosphate levels are typically targeted to be between 3.5 and 5.5 mg/dL (1.13-1.78 mmol/L) in patients on dialysis.

- Serum calcium levels are ideally maintained below 9.5 mg/dL (less than 2.37 mmol/L).

Once hyperphosphatemia is under control, PTH management is based on trends rather than isolated laboratory values. Notably, it is not advisable to suppress PTH to less than 2 times the upper limit, as it may lead to adynamic bone disease.[80](A1)

Phosphate: Phosphate management is critical for patients with persistent hyperphosphatemia exceeding 5.5 mg/dL, as elevated phosphate levels can complicate treatments for high PTH due to potential serum phosphate increases. Treatment initiation should occur if serum phosphate exceeds 5.5 mg/dL (1.78 mmol/L), given its association with mortality in dialysis patients.[82] Initial strategies often include phosphate restriction and the use of phosphate binders.[83] However, it is recommended to restrict dietary phosphate intake to 900 mg/d, and this should be overseen by a dietician, especially as many dialysis patients experience overt or borderline malnutrition. Typically, patients with hyperphosphatemia require dietary adjustments and phosphate binder medications, prompting clinicians to initiate both strategies for most patients with elevated phosphate levels. (A1)

Phosphate binders are categorized into calcium-containing and non-calcium–containing types. Calcium-containing binders include calcium carbonate and calcium acetate, whereas non-calcium–containing binders encompass lanthanum and sevelamer. Additional options comprise ferric citrate and sucroferric oxyhydroxide, all demonstrating comparable efficacy in phosphate reduction.[72] Typically, non-calcium–containing binders are preferred for most patients. However, in specific scenarios where non-calcium binders are not feasible or accessible, or in the presence of hypocalcemia and hyperparathyroidism (such as with adjunct calcimimetic therapy), calcium-containing binders may be considered. Nonetheless, many experts advise against the routine use of calcium-containing binders.[5] In addition to the above, clinicians should ensure that patients are adequately dialyzed and achieving recommended Kt/V targets. However, standard 4-hour dialysis sessions 3 times per week have limitations in removing phosphate, typically eliminating around 900 mg of phosphate per session.(A1)

Calcium: Maintaining calcium levels below 9.5 mg/dL (2.37 mmol/L) is essential. Asymptomatic and mild hypocalcemia does not require treatment due to the risk of hypercalcemia. In dialysis patients, calcium levels are maintained near the upper end of the normal range by adjusting the calcium concentration in the dialysate. This is done to suppress PTH and reduce the calcium and phosphorus (Ca x P) product. Hypocalcemia is associated with increased mortality and worsening hyperparathyroidism.[84] A different approach is adopted for patients with low bone turnover diseases. Efforts are made to prevent PTH suppression by reducing calcium and vitamin D levels. Non-calcium–containing binders are used to maintain phosphate levels without raising calcium levels, thus preventing PTH suppression. This strategy has been shown to increase bone formation rates.[85] The calcium concentration in the dialysate is also kept lower than standard dialysate levels for similar reasons. However, the advantages of stopping or restricting vitamin D intake remain uncertain.(A1)

Vitamin D: Correcting vitamin D deficiency is crucial, as low vitamin D levels have been associated with increased mortality among hemodialysis patients.[86] Both cholecalciferol and ergocalciferol are effective in correcting vitamin D levels.[87](A1)

Hyperparathyroidism: Treatment options for hyperparathyroidism include calcimimetics, calcitriol or synthetic vitamin D analogs, and a combination of both to decrease PTH levels.

In most cases, a combination is required as these agents are insufficient as monotherapy if PTH levels are very high.[88] Calcitriol or synthetic vitamin D analogs are discontinued or administered at a low dose if phosphate levels exceed 5.5 mg/dL or calcium levels above 10.2 mg/dL.[89] After hypercalcemia or hyperphosphatemia has resolved, these agents can be restarted at half the previous dose, or the patient may begin cinacalcet. Calcitriol or vitamin D analogs are typically initiated at a low dose (0.25 μg, 3 times a week). Response to treatment is usually observed within the first 3 to 6 months; dosage adjustments can be made at 4- to 8-week intervals if necessary.[90] Calcimimetics enhances the sensitivity of CaSR to calcium, leading to decreased serum PTH levels and subsequently lowering calcium and phosphate levels.[91] Cinacalcet (oral) and etelcalcetide (intravenous) are 2 widely available calcimimetics, with etelcalcetide typically reserved for refractory cases. Combining calcimimetics with ongoing calcitriol or vitamin D analogs and phosphate binders increases the likelihood of achieving target PTH levels without causing hypercalcemia or hyperphosphatemia.[92] Cinacalcet also reduces the likelihood of requiring a parathyroidectomy.[93] However, cinacalcet has not been found to improve mortality rates, and parathyroidectomy may be more effective, particularly for patients with very high PTH levels.[93] Historically, there have been 2 approaches to treating patients based on their phosphate and calcium levels, and providers typically choose a strategy based on their experience and available guidance.(A1)

The following approach is recommended in the 2017 KDIGO guidelines:

- Serum phosphate levels less than 5.5 mg/dL (1.78 mmol/L) and serum calcium levels less than 9.5 mg/dL (2.37 mmol/L): Such patients are initially treated with calcitriol monotherapy. The treatment goal is to increase the calcitriol dose to achieve target PTH levels while keeping serum phosphate below 5.5 mg/dL. If target PTH levels are not reached, cinacalcet can be initiated (assuming calcium levels are above 8.4 mg/dL). The initial cinacalcet dose is typically 30 mg/d, with gradual increments to 60, 90, and 180 mg/d as necessary.

- Serum phosphate levels greater than 5.4 mg/dL (1.78 mmol/L) or serum calcium levels greater than 9.4 mg/dL (2.37 mmol/L): In patients with these elevated levels and persistently high PTH despite maximal phosphate-reducing therapy, cinacalcet initiation takes precedence over calcitriol or other synthetic analogs. Cinacalcet usage should be avoided if calcium levels are less than 8.4 mg/dL (2.1 mmol/L) due to potential hypocalcemia risks. If target PTH levels are not achieved, the patient may be considered for calcitriol or synthetic vitamin D analogs, provided phosphate levels are below 5.5 mg/dL (1.78 mmol/L) and calcium levels are less than 9.5 mg/dL (2.37 mmol/L).

Differential Diagnosis

Patients showing signs and symptoms of bone disease or structural deformities undergo evaluation involving PTH, alkaline phosphatase, calcium, and phosphate levels. Although a history of CKD suggests CKD-MBD, ruling out other bone disorders, such as osteopenia, osteoporosis, vitamin D-resistant rickets, osteopetrosis, and Paget disease of the bone, is crucial to ensure accurate diagnosis and appropriate management.

Prognosis

Many studies have been conducted to establish a connection between deranged mineral metabolism in patients with CKD and mortality rates. Results from the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS) demonstrated a direct and independent association between abnormal mineral metabolism, including serum PTH, phosphate, calcium, vitamin D, and calcium-phosphorus product, and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality.[94] Hyperphosphatemia has been studied as a cause of increased mortality, particularly in patients with nondialysis CKD. A notable meta-analysis involving nearly 5000 patients with CKD highlighted a 35% increase in mortality per milligram rise in serum phosphate above the normal range.[82] Achieving complete recovery from renal osteodystrophy usually requires a renal transplant. However, when assessing the overall prognosis of this condition, it is crucial to consider other factors, such as the bone-vascular axis. Vascular calcifications, arteriosclerosis of blood vessels, and subsequent cardiovascular events in patients with renal osteodystrophy are all components of this axis. Understanding and addressing these interconnected factors are essential in determining the outcome for patients with this condition.[95]

Complications

CKD-MBD is itself a complication of CKD. Once mineral bone disease develops, patients commonly experience bone pain, and skeletal deformities, while growth retardation may occur in children. Another significant complication of CKD-MBD is the gradual deterioration of cardiac parameters, including cardiac remodeling and vascular calcification. However, treatment for CKD-MBD, such as using lower calcium dialysate and calcimimetics, can lead to fatal arrhythmias due to QT prolongation. Sudden fatal cardiac events, such as sudden cardiac death or heart failure resulting from severe arrhythmias, represent a distinctive phenomenon that may be characterized as part of the CKD-MBD–specific cardiac complex syndrome.[96] Results from studies have indicated that patients with renal osteodystrophy and a history of initial fragility fracture are more likely to experience cardiovascular events and metastatic calcification.[97] Additionally, complications such as increased infections, muscle weakness, arrhythmias, and heightened risk of hemorrhagic stroke may also be associated with CKD-MBD.

Consultations

CKD-MBD management may involve consultation with the specialties, including nephrology, endocrinology, dietetics/nutrition, general surgery, orthopedic surgery, and cardiology, based on the patient's presentation and future risks.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients should be educated regarding the roles of phosphate, calcium, vitamin D, and PTH in their condition. Furthermore, referrals to a dietitian are crucial for providing personalized diet recommendations, including a phosphate-restricted diet while ensuring adequate protein intake. Malnutrition is prevalent in CKD-MBD, and dietary phosphate restriction can help prevent secondary hyperparathyroidism.[98] Patients should also understand the types of phosphate binders and the importance of taking them with meals. In some cases, calcium and vitamin D supplementation may also be necessary.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

CKD-MBD, a complication of CKD, arises from the imbalance of calcium, phosphate, and PTH, resulting in nephron function loss in patients. Clinical presentations range widely from asymptomatic to bone fractures, with an elevated risk of cardiovascular events linked to chronic hypertension. While many patients may exhibit similar symptoms, it is crucial to recognize that underlying causes can vary, necessitating diverse treatment approaches. Even patients undergoing routine dialysis may experience this complication and require appropriate management. Although nephrologists are critical in treating patients with renal osteodystrophy, collaboration with other healthcare team members is crucial. Communication with an orthopedic surgeon is essential for managing bone fractures in patients, if present. Furthermore, the outpatient internist or general clinician has a significant role in monitoring a patient's daily symptoms and closely observing any cardiovascular involvement on an outpatient basis.

Consulting a cardiologist may be necessary if a patient develops vascular calcifications, arrhythmia, or left ventricular hypertrophy. Pharmacists review all medications, highlighting any nephrotoxic drugs the patient might be prescribed. The dialysis team, comprising nephrologists, nurses, and technicians, has a vital role in treating patients with end-stage renal disease. Regular imaging is conducted in patients with renal osteodystrophy, involving the radiologist's expertise. Radiological evidence of hyperparathyroidism can be observed and may aid in identifying underlying bone diseases. Confirming the diagnosis may require a specialist's expertise through bone biopsies. An integrated and interprofessional approach is recommended for patients with chronic renal failure and its associated complications to reduce morbidity and enhance outcomes.[99]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Systemic Impact of CKD-MBD. Chronic Kidney Disease–Mineral Bone Disorder (CKD-MBD) has far-reaching effects on various organs and systems due to dysregulated humoral mediators.

Yamada S, Tsuruya K, Kitazono T, Nakano T. Emerging cross-talks between chronic kidney disease–mineral and bone disorder (CKD–MBD) and malnutrition-inflammation complex syndrome (MICS) in patients receiving dialysis. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2022;26(7):613-629. doi: 10.1007/s10157-022-02216-x.

References

Moe S, Drüeke T, Cunningham J, Goodman W, Martin K, Olgaard K, Ott S, Sprague S, Lameire N, Eknoyan G, Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Definition, evaluation, and classification of renal osteodystrophy: a position statement from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Kidney international. 2006 Jun:69(11):1945-53 [PubMed PMID: 16641930]

Isakova T, Cai X, Lee J, Mehta R, Zhang X, Yang W, Nessel L, Anderson AH, Lo J, Porter A, Nunes JW, Negrea L, Hamm L, Horwitz E, Chen J, Scialla JJ, de Boer IH, Leonard MB, Feldman HI, Wolf M, CRIC Study Investigators. Longitudinal Evolution of Markers of Mineral Metabolism in Patients With CKD: The Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2020 Feb:75(2):235-244. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.07.022. Epub 2019 Oct 23 [PubMed PMID: 31668375]

Fang Y, Ginsberg C, Sugatani T, Monier-Faugere MC, Malluche H, Hruska KA. Early chronic kidney disease-mineral bone disorder stimulates vascular calcification. Kidney international. 2014 Jan:85(1):142-50. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.271. Epub 2013 Jul 24 [PubMed PMID: 23884339]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRuospo M, Palmer SC, Natale P, Craig JC, Vecchio M, Elder GJ, Strippoli GF. Phosphate binders for preventing and treating chronic kidney disease-mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD). The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2018 Aug 22:8(8):CD006023. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006023.pub3. Epub 2018 Aug 22 [PubMed PMID: 30132304]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKetteler M, Block GA, Evenepoel P, Fukagawa M, Herzog CA, McCann L, Moe SM, Shroff R, Tonelli MA, Toussaint ND, Vervloet MG, Leonard MB. Executive summary of the 2017 KDIGO Chronic Kidney Disease-Mineral and Bone Disorder (CKD-MBD) Guideline Update: what's changed and why it matters. Kidney international. 2017 Jul:92(1):26-36. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2017.04.006. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28646995]

Cunningham J, Locatelli F, Rodriguez M. Secondary hyperparathyroidism: pathogenesis, disease progression, and therapeutic options. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2011 Apr:6(4):913-21. doi: 10.2215/CJN.06040710. Epub 2011 Mar 31 [PubMed PMID: 21454719]

Gutierrez O, Isakova T, Rhee E, Shah A, Holmes J, Collerone G, Jüppner H, Wolf M. Fibroblast growth factor-23 mitigates hyperphosphatemia but accentuates calcitriol deficiency in chronic kidney disease. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2005 Jul:16(7):2205-15 [PubMed PMID: 15917335]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHo LT, Sprague SM. Renal osteodystrophy in chronic renal failure. Seminars in nephrology. 2002 Nov:22(6):488-93 [PubMed PMID: 12430093]

Slatopolsky E, Gonzalez E, Martin K. Pathogenesis and treatment of renal osteodystrophy. Blood purification. 2003:21(4-5):318-26 [PubMed PMID: 12944733]

Georgiadou E, Marketou H, Trovas G, Dontas I, Papaioannou N, Makris K, Galanos A, Papavassiliou AG. Effect of Calcitriol on FGF23 Level in Healthy Adults and its Dependence on Phosphate Level. In vivo (Athens, Greece). 2017 Jan 2:31(1):145-150 [PubMed PMID: 28064234]

Yamada S, Tsuruya K, Kitazono T, Nakano T. Emerging cross-talks between chronic kidney disease-mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD) and malnutrition-inflammation complex syndrome (MICS) in patients receiving dialysis. Clinical and experimental nephrology. 2022 Jul:26(7):613-629. doi: 10.1007/s10157-022-02216-x. Epub 2022 Mar 30 [PubMed PMID: 35353283]

Llach F. Secondary hyperparathyroidism in renal failure: the trade-off hypothesis revisited. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 1995 May:25(5):663-79 [PubMed PMID: 7747720]

Bricker NS. On the pathogenesis of the uremic state. An exposition of the "trade-off hypothesis". The New England journal of medicine. 1972 May 18:286(20):1093-9 [PubMed PMID: 4553202]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSilver J, Rodriguez M, Slatopolsky E. FGF23 and PTH--double agents at the heart of CKD. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2012 May:27(5):1715-20. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs050. Epub 2012 Mar 23 [PubMed PMID: 22447519]

Isakova T, Wahl P, Vargas GS, Gutiérrez OM, Scialla J, Xie H, Appleby D, Nessel L, Bellovich K, Chen J, Hamm L, Gadegbeku C, Horwitz E, Townsend RR, Anderson CA, Lash JP, Hsu CY, Leonard MB, Wolf M. Fibroblast growth factor 23 is elevated before parathyroid hormone and phosphate in chronic kidney disease. Kidney international. 2011 Jun:79(12):1370-8. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.47. Epub 2011 Mar 9 [PubMed PMID: 21389978]

Wetmore JB, Liu S, Krebill R, Menard R, Quarles LD. Effects of cinacalcet and concurrent low-dose vitamin D on FGF23 levels in ESRD. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2010 Jan:5(1):110-6. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03630509. Epub 2009 Nov 5 [PubMed PMID: 19965548]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencePaloian NJ, Giachelli CM. A current understanding of vascular calcification in CKD. American journal of physiology. Renal physiology. 2014 Oct 15:307(8):F891-900. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00163.2014. Epub 2014 Aug 20 [PubMed PMID: 25143458]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCourbebaisse M, Lanske B. Biology of Fibroblast Growth Factor 23: From Physiology to Pathology. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine. 2018 May 1:8(5):. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a031260. Epub 2018 May 1 [PubMed PMID: 28778965]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSlatopolsky E, Weerts C, Thielan J, Horst R, Harter H, Martin KJ. Marked suppression of secondary hyperparathyroidism by intravenous administration of 1,25-dihydroxy-cholecalciferol in uremic patients. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1984 Dec:74(6):2136-43 [PubMed PMID: 6549016]

Rodriguez M, Nemeth E, Martin D. The calcium-sensing receptor: a key factor in the pathogenesis of secondary hyperparathyroidism. American journal of physiology. Renal physiology. 2005 Feb:288(2):F253-64 [PubMed PMID: 15507543]

Block GA, Hulbert-Shearon TE, Levin NW, Port FK. Association of serum phosphorus and calcium x phosphate product with mortality risk in chronic hemodialysis patients: a national study. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 1998 Apr:31(4):607-17 [PubMed PMID: 9531176]

Quinn SJ, Thomsen AR, Pang JL, Kantham L, Bräuner-Osborne H, Pollak M, Goltzman D, Brown EM. Interactions between calcium and phosphorus in the regulation of the production of fibroblast growth factor 23 in vivo. American journal of physiology. Endocrinology and metabolism. 2013 Feb 1:304(3):E310-20. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00460.2012. Epub 2012 Dec 11 [PubMed PMID: 23233539]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceImanishi Y, Inaba M, Nakatsuka K, Nagasue K, Okuno S, Yoshihara A, Miura M, Miyauchi A, Kobayashi K, Miki T, Shoji T, Ishimura E, Nishizawa Y. FGF-23 in patients with end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis. Kidney international. 2004 May:65(5):1943-6 [PubMed PMID: 15086938]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSaito H, Kusano K, Kinosaki M, Ito H, Hirata M, Segawa H, Miyamoto K, Fukushima N. Human fibroblast growth factor-23 mutants suppress Na+-dependent phosphate co-transport activity and 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 production. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003 Jan 24:278(4):2206-11 [PubMed PMID: 12419819]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBen-Dov IZ, Galitzer H, Lavi-Moshayoff V, Goetz R, Kuro-o M, Mohammadi M, Sirkis R, Naveh-Many T, Silver J. The parathyroid is a target organ for FGF23 in rats. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2007 Dec:117(12):4003-8 [PubMed PMID: 17992255]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceUrakawa I, Yamazaki Y, Shimada T, Iijima K, Hasegawa H, Okawa K, Fujita T, Fukumoto S, Yamashita T. Klotho converts canonical FGF receptor into a specific receptor for FGF23. Nature. 2006 Dec 7:444(7120):770-4 [PubMed PMID: 17086194]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHu MC, Kuro-o M, Moe OW. Klotho and chronic kidney disease. Contributions to nephrology. 2013:180():47-63. doi: 10.1159/000346778. Epub 2013 May 3 [PubMed PMID: 23652549]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSchwarz U, Buzello M, Ritz E, Stein G, Raabe G, Wiest G, Mall G, Amann K. Morphology of coronary atherosclerotic lesions in patients with end-stage renal failure. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2000 Feb:15(2):218-23 [PubMed PMID: 10648668]

Qunibi WY, Abouzahr F, Mizani MR, Nolan CR, Arya R, Hunt KJ. Cardiovascular calcification in Hispanic Americans (HA) with chronic kidney disease (CKD) due to type 2 diabetes. Kidney international. 2005 Jul:68(1):271-7 [PubMed PMID: 15954917]

Budoff MJ, Rader DJ, Reilly MP, Mohler ER 3rd, Lash J, Yang W, Rosen L, Glenn M, Teal V, Feldman HI, CRIC Study Investigators. Relationship of estimated GFR and coronary artery calcification in the CRIC (Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort) Study. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2011 Oct:58(4):519-26. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.04.024. Epub 2011 Jul 23 [PubMed PMID: 21783289]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceChuang SH, Wong HC, Vathsala A, Lee E, How PP. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease-mineral and bone disorder in incident peritoneal dialysis patients and its association with short-term outcomes. Singapore medical journal. 2016 Nov:57(11):603-609. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2015195. Epub 2015 Dec 29 [PubMed PMID: 26778726]

Martin KJ, Olgaard K, Coburn JW, Coen GM, Fukagawa M, Langman C, Malluche HH, McCarthy JT, Massry SG, Mehls O, Salusky IB, Silver JM, Smogorzewski MT, Slatopolsky EM, McCann L, Bone Turnover Work Group. Diagnosis, assessment, and treatment of bone turnover abnormalities in renal osteodystrophy. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2004 Mar:43(3):558-65 [PubMed PMID: 14981615]

Goodman WG, Ramirez JA, Belin TR, Chon Y, Gales B, Segre GV, Salusky IB. Development of adynamic bone in patients with secondary hyperparathyroidism after intermittent calcitriol therapy. Kidney international. 1994 Oct:46(4):1160-6 [PubMed PMID: 7861712]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencePei Y, Hercz G, Greenwood C, Segre G, Manuel A, Saiphoo C, Fenton S, Sherrard D. Renal osteodystrophy in diabetic patients. Kidney international. 1993 Jul:44(1):159-64 [PubMed PMID: 8355457]

Moe SM, Drüeke TB. A bridge to improving healthcare outcomes and quality of life. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2004 Mar:43(3):552-7 [PubMed PMID: 14981614]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceD'Haese PC, Spasovski GB, Sikole A, Hutchison A, Freemont TJ, Sulkova S, Swanepoel C, Pejanovic S, Djukanovic L, Balducci A, Coen G, Sulowicz W, Ferreira A, Torres A, Curic S, Popovic M, Dimkovic N, De Broe ME. A multicenter study on the effects of lanthanum carbonate (Fosrenol) and calcium carbonate on renal bone disease in dialysis patients. Kidney international. Supplement. 2003 Jun:(85):S73-8 [PubMed PMID: 12753271]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLeifheit-Nestler M, Haffner D. How FGF23 shapes multiple organs in chronic kidney disease. Molecular and cellular pediatrics. 2021 Sep 18:8(1):12. doi: 10.1186/s40348-021-00123-x. Epub 2021 Sep 18 [PubMed PMID: 34536161]

Hruska KA, Teitelbaum SL. Renal osteodystrophy. The New England journal of medicine. 1995 Jul 20:333(3):166-74 [PubMed PMID: 7791820]

Naji Rad S, Anastasopoulou C, Barnett MJ, Deluxe L. Osteitis Fibrosa Cystica. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32644523]

Naveh-Many T, Rahamimov R, Livni N, Silver J. Parathyroid cell proliferation in normal and chronic renal failure rats. The effects of calcium, phosphate, and vitamin D. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1995 Oct:96(4):1786-93 [PubMed PMID: 7560070]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceElder G. Pathophysiology and recent advances in the management of renal osteodystrophy. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2002 Dec:17(12):2094-105 [PubMed PMID: 12469904]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBrandenburg VM, Floege J. Adynamic bone disease-bone and beyond. NDT plus. 2008 Jun:1(3):135-47. doi: 10.1093/ndtplus/sfn040. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25983860]

Stathi D, Fountoulakis N, Panagiotou A, Maltese G, Corcillo A, Mangelis A, Ayis S, Gnudi L, Karalliedde J. Impact of treatment with active vitamin D calcitriol on bone turnover markers in people with type 2 diabetes and stage 3 chronic kidney disease. Bone. 2023 Jan:166():116581. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2022.116581. Epub 2022 Oct 8 [PubMed PMID: 36216304]

Sugimoto T, Ritter C, Morrissey J, Hayes C, Slatopolsky E. Effects of high concentrations of glucose on PTH secretion in parathyroid cells. Kidney international. 1990 Jun:37(6):1522-7 [PubMed PMID: 2194068]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceViegas CSB, Santos L, Macedo AL, Matos AA, Silva AP, Neves PL, Staes A, Gevaert K, Morais R, Vermeer C, Schurgers L, Simes DC. Chronic Kidney Disease Circulating Calciprotein Particles and Extracellular Vesicles Promote Vascular Calcification: A Role for GRP (Gla-Rich Protein). Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2018 Mar:38(3):575-587. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.117.310578. Epub 2018 Jan 4 [PubMed PMID: 29301790]

Köppert S, Büscher A, Babler A, Ghallab A, Buhl EM, Latz E, Hengstler JG, Smith ER, Jahnen-Dechent W. Cellular Clearance and Biological Activity of Calciprotein Particles Depend on Their Maturation State and Crystallinity. Frontiers in immunology. 2018:9():1991. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01991. Epub 2018 Sep 4 [PubMed PMID: 30233585]

Yamada S, Nakano T. Role of Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD)-Mineral and Bone Disorder (MBD) in the Pathogenesis of Cardiovascular Disease in CKD. Journal of atherosclerosis and thrombosis. 2023 Aug 1:30(8):835-850. doi: 10.5551/jat.RV22006. Epub 2023 May 30 [PubMed PMID: 37258233]

Xie J, Yoon J, An SW, Kuro-o M, Huang CL. Soluble Klotho Protects against Uremic Cardiomyopathy Independently of Fibroblast Growth Factor 23 and Phosphate. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2015 May:26(5):1150-60. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014040325. Epub 2014 Dec 4 [PubMed PMID: 25475745]

McGrath ER, Himali JJ, Levy D, Conner SC, Pase MP, Abraham CR, Courchesne P, Satizabal CL, Vasan RS, Beiser AS, Seshadri S. Circulating fibroblast growth factor 23 levels and incident dementia: The Framingham heart study. PloS one. 2019:14(3):e0213321. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0213321. Epub 2019 Mar 4 [PubMed PMID: 30830941]

Yamada S, Tsuruya K, Taniguchi M, Tokumoto M, Fujisaki K, Hirakata H, Fujimi S, Kitazono T. Association Between Serum Phosphate Levels and Stroke Risk in Patients Undergoing Hemodialysis: The Q-Cohort Study. Stroke. 2016 Sep:47(9):2189-96. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.013195. Epub 2016 Aug 9 [PubMed PMID: 27507862]

Tagawa M, Hamano T, Nishi H, Tsuchida K, Hanafusa N, Fukatsu A, Iseki K, Tsubakihara Y. Mineral Metabolism Markers Are Associated with Myocardial Infarction and Hemorrhagic Stroke but Not Ischemic Stroke in Hemodialysis Patients: A Longitudinal Study. PloS one. 2014:9(12):e114678. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114678. Epub 2014 Dec 10 [PubMed PMID: 25494334]

Yang X, Cai S, Gong J, Zhang J, Lian M, Chen R, Zhou L, Bai P, Liu B, Zhuang M, Tan H, Xu J, Li M. Characterization of gut microbiota in patients with stage 3-4 chronic kidney disease: a retrospective cohort study. International urology and nephrology. 2024 May:56(5):1751-1762. doi: 10.1007/s11255-023-03893-7. Epub 2023 Dec 12 [PubMed PMID: 38085410]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFavero C, Carriazo S, Cuarental L, Fernandez-Prado R, Gomá-Garcés E, Perez-Gomez MV, Ortiz A, Fernandez-Fernandez B, Sanchez-Niño MD. Phosphate, Microbiota and CKD. Nutrients. 2021 Apr 13:13(4):. doi: 10.3390/nu13041273. Epub 2021 Apr 13 [PubMed PMID: 33924419]

Cernaro V, Longhitano E, Calabrese V, Casuscelli C, Di Carlo S, Spinella C, Gembillo G, Santoro D. Progress in pharmacotherapy for the treatment of hyperphosphatemia in renal failure. Expert opinion on pharmacotherapy. 2023 Sep-Dec:24(15):1737-1746. doi: 10.1080/14656566.2023.2243817. Epub 2023 Aug 11 [PubMed PMID: 37527180]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYamada S, Arase H, Tokumoto M, Taniguchi M, Yoshida H, Nakano T, Tsuruya K, Kitazono T. Increased Risk of Infection-Related and All-Cause Death in Hypercalcemic Patients Receiving Hemodialysis: The Q-Cohort Study. Scientific reports. 2020 Apr 14:10(1):6327. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-63334-8. Epub 2020 Apr 14 [PubMed PMID: 32286455]

Zheng L, Hunter K, Gaughan J, Poddar S. Preadmission Use of Calcium Channel Blockers and Outcomes After Hospitalization With Pneumonia: A Retrospective Propensity-Matched Cohort Study. American journal of therapeutics. 2017 Jan/Feb:24(1):e30-e38. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0000000000000312. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26280292]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWiewel MA, van Vught LA, Scicluna BP, Hoogendijk AJ, Frencken JF, Zwinderman AH, Horn J, Cremer OL, Bonten MJ, Schultz MJ, van der Poll T, Molecular Diagnosis and Risk Stratification of Sepsis (MARS) Consortium. Prior Use of Calcium Channel Blockers Is Associated With Decreased Mortality in Critically Ill Patients With Sepsis: A Prospective Observational Study. Critical care medicine. 2017 Mar:45(3):454-463. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002236. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28079604]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKomaba H, Zhao J, Yamamoto S, Nomura T, Fuller DS, McCullough KP, Evenepoel P, Christensson A, Zhao X, Alrukhaimi M, Al-Ali F, Young EW, Robinson BM, Fukagawa M. Secondary hyperparathyroidism, weight loss, and longer term mortality in haemodialysis patients: results from the DOPPS. Journal of cachexia, sarcopenia and muscle. 2021 Aug:12(4):855-865. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12722. Epub 2021 Jun 1 [PubMed PMID: 34060245]

Nebeker HG, Coburn JW. Aluminum and renal osteodystrophy. Annual review of medicine. 1986:37():79-95 [PubMed PMID: 3085581]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePiraino B, Chen T, Cooperstein L, Segre G, Puschett J. Fractures and vertebral bone mineral density in patients with renal osteodystrophy. Clinical nephrology. 1988 Aug:30(2):57-62 [PubMed PMID: 3180516]

Kurz P, Monier-Faugere MC, Bognar B, Werner E, Roth P, Vlachojannis J, Malluche HH. Evidence for abnormal calcium homeostasis in patients with adynamic bone disease. Kidney international. 1994 Sep:46(3):855-61 [PubMed PMID: 7996807]

Moody WE, Edwards NC, Chue CD, Ferro CJ, Townend JN. Arterial disease in chronic kidney disease. Heart (British Cardiac Society). 2013 Mar:99(6):365-72. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2012-302818. Epub 2012 Oct 31 [PubMed PMID: 23118349]

Westphal SG, Plumb T. Calciphylaxis. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30085562]

Kemper MJ, van Husen M. Renal osteodystrophy in children: pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. Current opinion in pediatrics. 2014 Apr:26(2):180-6. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000061. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24553631]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceEsfahani DR, Alaraj A, Birk DM, Thulborn KR, Charbel FT. Stenosis Before Thrombosis: Intracranial Hypertension from Jugular Foramen Stenosis Secondary to Renal Osteodystrophy. World neurosurgery. 2018 Jan:109():129-133. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.09.106. Epub 2017 Sep 23 [PubMed PMID: 28951273]

Donoso-Hofer F, Gunther-Wood M, Romero-Romano P, Pezoa-Opazo N, Fernández-Toro MA, Ortega-Pinto AV. Uremic leontiasis ossea, a rare presentation of severe renal osteodystrophy secondary to hyperparathyroidism. Journal of stomatology, oral and maxillofacial surgery. 2018 Feb:119(1):56-60. doi: 10.1016/j.jormas.2017.10.006. Epub 2017 Oct 14 [PubMed PMID: 29037869]

Schwarz C, Sulzbacher I, Oberbauer R. Diagnosis of renal osteodystrophy. European journal of clinical investigation. 2006 Aug:36 Suppl 2():13-22 [PubMed PMID: 16884394]

Smith ER, McMahon LP, Holt SG. Fibroblast growth factor 23. Annals of clinical biochemistry. 2014 Mar:51(Pt 2):203-27. doi: 10.1177/0004563213510708. Epub 2013 Nov 22 [PubMed PMID: 24269946]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSprague SM, Bellorin-Font E, Jorgetti V, Carvalho AB, Malluche HH, Ferreira A, D'Haese PC, Drüeke TB, Du H, Manley T, Rojas E, Moe SM. Diagnostic Accuracy of Bone Turnover Markers and Bone Histology in Patients With CKD Treated by Dialysis. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2016 Apr:67(4):559-66. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.06.023. Epub 2015 Aug 25 [PubMed PMID: 26321176]

Moorthi RN, Armstrong CL, Janda K, Ponsler-Sipes K, Asplin JR, Moe SM. The effect of a diet containing 70% protein from plants on mineral metabolism and musculoskeletal health in chronic kidney disease. American journal of nephrology. 2014:40(6):582-91. doi: 10.1159/000371498. Epub 2015 Jan 20 [PubMed PMID: 25613675]

Meng L, Fu B. Practical use of sevelamer in chronic kidney disease patients on dialysis in People's Republic of China. Therapeutics and clinical risk management. 2015:11():705-12. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S64657. Epub 2015 Apr 30 [PubMed PMID: 25995642]

National Kidney Foundation. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for bone metabolism and disease in chronic kidney disease. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2003 Oct:42(4 Suppl 3):S1-201 [PubMed PMID: 14520607]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHill KM, Martin BR, Wastney ME, McCabe GP, Moe SM, Weaver CM, Peacock M. Oral calcium carbonate affects calcium but not phosphorus balance in stage 3-4 chronic kidney disease. Kidney international. 2013 May:83(5):959-66. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.403. Epub 2012 Dec 19 [PubMed PMID: 23254903]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKramer H, Berns JS, Choi MJ, Martin K, Rocco MV. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D testing and supplementation in CKD: an NKF-KDOQI controversies report. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2014 Oct:64(4):499-509. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.05.018. Epub 2014 Jul 28 [PubMed PMID: 25082101]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKandula P, Dobre M, Schold JD, Schreiber MJ Jr, Mehrotra R, Navaneethan SD. Vitamin D supplementation in chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies and randomized controlled trials. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2011 Jan:6(1):50-62. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03940510. Epub 2010 Sep 28 [PubMed PMID: 20876671]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceWang AY, Fang F, Chan J, Wen YY, Qing S, Chan IH, Lo G, Lai KN, Lo WK, Lam CW, Yu CM. Effect of paricalcitol on left ventricular mass and function in CKD--the OPERA trial. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2014 Jan:25(1):175-86. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013010103. Epub 2013 Sep 19 [PubMed PMID: 24052631]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceThadhani R, Appelbaum E, Pritchett Y, Chang Y, Wenger J, Tamez H, Bhan I, Agarwal R, Zoccali C, Wanner C, Lloyd-Jones D, Cannata J, Thompson BT, Andress D, Zhang W, Packham D, Singh B, Zehnder D, Shah A, Pachika A, Manning WJ, Solomon SD. Vitamin D therapy and cardiac structure and function in patients with chronic kidney disease: the PRIMO randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2012 Feb 15:307(7):674-84. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.120. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22337679]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSlatopolsky E, Berkoben M, Kelber J, Brown A, Delmez J. Effects of calcitriol and non-calcemic vitamin D analogs on secondary hyperparathyroidism. Kidney international. Supplement. 1992 Oct:38():S43-9 [PubMed PMID: 1405381]

Chonchol M, Locatelli F, Abboud HE, Charytan C, de Francisco AL, Jolly S, Kaplan M, Roger SD, Sarkar S, Albizem MB, Mix TC, Kubo Y, Block GA. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to assess the efficacy and safety of cinacalcet HCl in participants with CKD not receiving dialysis. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2009 Feb:53(2):197-207. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.09.021. Epub 2008 Dec 24 [PubMed PMID: 19110359]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD-MBD Work Group. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, prevention, and treatment of Chronic Kidney Disease-Mineral and Bone Disorder (CKD-MBD). Kidney international. Supplement. 2009 Aug:(113):S1-130. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.188. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19644521]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMcCann L. K/DOQI practice guidelines for bone metabolism and disease in chronic kidney disease: another opportunity for renal dietitians to take a leadership role in improving outcomes for patients with chronic kidney disease. Journal of renal nutrition : the official journal of the Council on Renal Nutrition of the National Kidney Foundation. 2005 Apr:15(2):265-74 [PubMed PMID: 15827902]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencePalmer SC, Hayen A, Macaskill P, Pellegrini F, Craig JC, Elder GJ, Strippoli GF. Serum levels of phosphorus, parathyroid hormone, and calcium and risks of death and cardiovascular disease in individuals with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2011 Mar 16:305(11):1119-27. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.308. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21406649]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceJindal K, Chan CT, Deziel C, Hirsch D, Soroka SD, Tonelli M, Culleton BF, Canadian Society of Nephrology Committee for Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hemodialysis clinical practice guidelines for the Canadian Society of Nephrology. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2006 Mar:17(3 Suppl 1):S1-27 [PubMed PMID: 16497879]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceFloege J, Kim J, Ireland E, Chazot C, Drueke T, de Francisco A, Kronenberg F, Marcelli D, Passlick-Deetjen J, Schernthaner G, Fouqueray B, Wheeler DC, ARO Investigators. Serum iPTH, calcium and phosphate, and the risk of mortality in a European haemodialysis population. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2011 Jun:26(6):1948-55. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq219. Epub 2010 Apr 25 [PubMed PMID: 20466670]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFerreira A, Frazão JM, Monier-Faugere MC, Gil C, Galvao J, Oliveira C, Baldaia J, Rodrigues I, Santos C, Ribeiro S, Hoenger RM, Duggal A, Malluche HH, Sevelamer Study Group. Effects of sevelamer hydrochloride and calcium carbonate on renal osteodystrophy in hemodialysis patients. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2008 Feb:19(2):405-12. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006101089. Epub 2008 Jan 16 [PubMed PMID: 18199805]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMailliez S, Shahapuni I, Lecaque C, Massy ZA, Choukroun G, Fournier A. Vitamin D levels and early mortality among incident hemodialysis patients. Kidney international. 2008 Aug:74(3):389; author reply 389. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.168. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18626498]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMassart A, Debelle FD, Racapé J, Gervy C, Husson C, Dhaene M, Wissing KM, Nortier JL. Biochemical parameters after cholecalciferol repletion in hemodialysis: results From the VitaDial randomized trial. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2014 Nov:64(5):696-705. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.04.020. Epub 2014 May 22 [PubMed PMID: 24856872]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMalberti F, Corradi B, Cosci P, Calliada F, Marcelli D, Imbasciati E. Long-term effects of intravenous calcitriol therapy on the control of secondary hyperparathyroidism. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 1996 Nov:28(5):704-12 [PubMed PMID: 9158208]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSakaguchi T, Akizawa T. [K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for bone metabolism and disease in CKD]. Clinical calcium. 2004 Sep:14(9):9-14 [PubMed PMID: 15577103]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceQuarles LD, Davidai GA, Schwab SJ, Bartholomay DW, Lobaugh B. Oral calcitriol and calcium: efficient therapy for uremic hyperparathyroidism. Kidney international. 1988 Dec:34(6):840-4 [PubMed PMID: 3210546]

Palmer SC, Mavridis D, Johnson DW, Tonelli M, Ruospo M, Strippoli GFM. Comparative Effectiveness of Calcimimetic Agents for Secondary Hyperparathyroidism in Adults: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2020 Sep:76(3):321-330. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2020.02.439. Epub 2020 May 28 [PubMed PMID: 32475604]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMessa P, Macário F, Yaqoob M, Bouman K, Braun J, von Albertini B, Brink H, Maduell F, Graf H, Frazão JM, Bos WJ, Torregrosa V, Saha H, Reichel H, Wilkie M, Zani VJ, Molemans B, Carter D, Locatelli F. The OPTIMA study: assessing a new cinacalcet (Sensipar/Mimpara) treatment algorithm for secondary hyperparathyroidism. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2008 Jan:3(1):36-45. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03591006. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18178780]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencePalmer SC, Nistor I, Craig JC, Pellegrini F, Messa P, Tonelli M, Covic A, Strippoli GF. Cinacalcet in patients with chronic kidney disease: a cumulative meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS medicine. 2013:10(4):e1001436. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001436. Epub 2013 Apr 30 [PubMed PMID: 23637579]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceYoung EW, Akiba T, Albert JM, McCarthy JT, Kerr PG, Mendelssohn DC, Jadoul M. Magnitude and impact of abnormal mineral metabolism in hemodialysis patients in the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2004 Nov:44(5 Suppl 2):34-8 [PubMed PMID: 15486872]

London GM. Bone-vascular axis in chronic kidney disease: a reality? Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2009 Feb:4(2):254-7. doi: 10.2215/CJN.06661208. Epub 2009 Jan 28 [PubMed PMID: 19176792]

Fujii H, Joki N. Mineral metabolism and cardiovascular disease in CKD. Clinical and experimental nephrology. 2017 Mar:21(Suppl 1):53-63. doi: 10.1007/s10157-016-1363-8. Epub 2017 Jan 6 [PubMed PMID: 28062938]

Li C, Chen XM, Li Y, Zhou YL, Yan JN, Du XG. Factors and Outcome of Renal Osteodystrophy-Associated Initial Fragility Fracture in End-Stage Renal Disease Patients. Kidney diseases (Basel, Switzerland). 2019 Mar:5(2):118-125. doi: 10.1159/000494924. Epub 2019 Feb 6 [PubMed PMID: 31019925]

Aparicio M, Lafage MH, Combe C, de Precigout V, Bouchet JL, Potaux L. Low-protein diet and renal osteodystrophy. Nephron. 1991:58(2):250-2 [PubMed PMID: 1865990]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGhimire S, Lee K, Jose MD, Castelino RL, Zaidi STR. Adherence assessment practices in haemodialysis settings: A qualitative exploration of nurses and pharmacists' perspectives. Journal of clinical nursing. 2019 Jun:28(11-12):2197-2205. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14821. Epub 2019 Mar 12 [PubMed PMID: 30786082]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence