Introduction

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a progressive lung disorder characterized by scarring of the lungs from an unknown cause. The condition has a poor long-term prognosis. Classical features of IPF include the gradual onset of shortness of breath, progressive dyspnea, and a dry, nonproductive cough. Pulmonary function tests (PFTs) usually reveal restrictive lung function impairment, decreased functional vital capacity, and diminished carbon monoxide diffusing capacity. Early diagnosis is pivotal for effective management, given the disease's tendency to progress rapidly in advanced stages. Diagnosis can often be established without biopsy through a comprehensive assessment of clinical history, imaging results, and exclusion of alternative conditions.

Classic imaging patterns on computed tomography (CT) scans typically reveal a peripheral distribution of bilateral fibrosis, particularly accentuated at the bases.[1] However, a lung biopsy may be required in cases where diagnostic uncertainty persists.[2][3][4] Notably, lung biopsy in any form carries inherent risks. Generally, it is avoided for patients with newly detected interstitial lung disease (ILD) showing a usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) pattern on high-resolution CT (HRCT) scans.[5] Treatment strategies include supportive measures, oxygen supplementation as needed, antifibrotic medications, and lung transplantation for severe cases, representing the sole known curative option.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

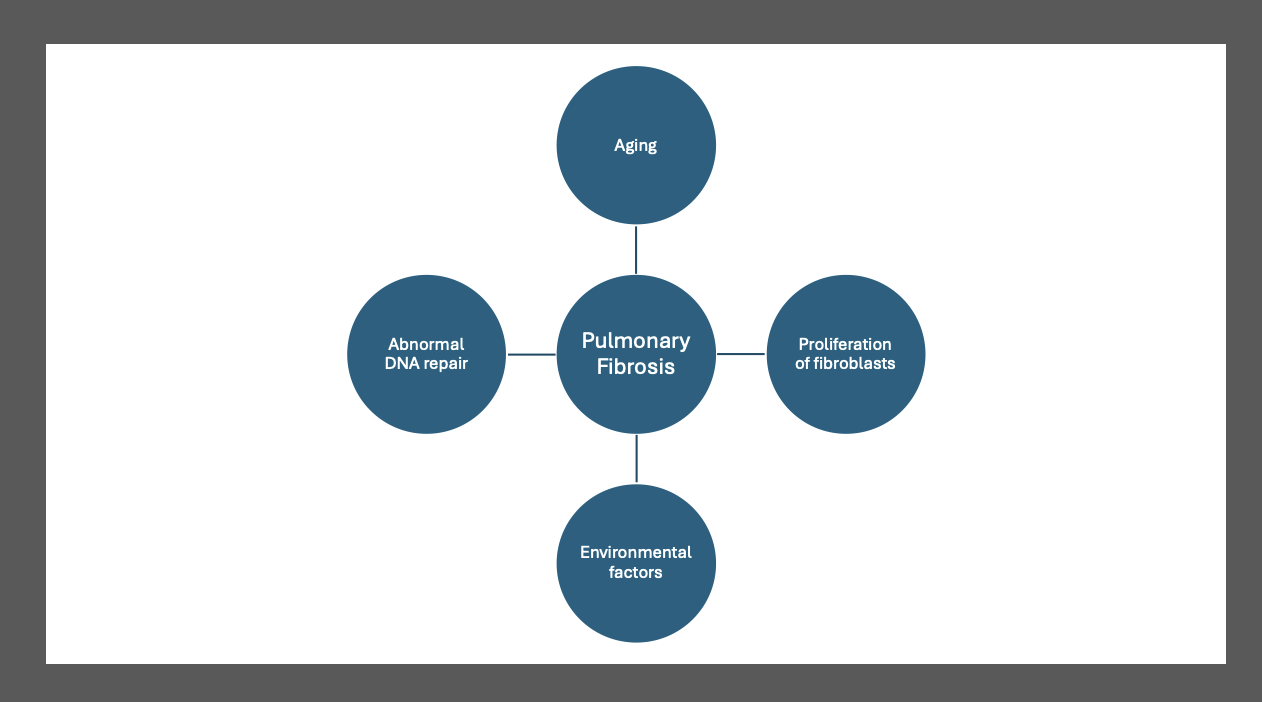

The exact etiology of the development of IPF is unknown. The characteristic feature involves abnormal fibroblast activation and subsequent deposition of extracellular matrix by these cells.[6] The current theory on the etiology of IPF suggests that recurrent injury to the alveolar epithelium triggers a cascade of signaling by the immune system, leading to fibroblast formation. Additional mechanisms contributing to IPF may include impaired DNA repair and abnormal folding and processing of surfactant proteins.[7]

A dysregulated response to the injury can cause tissue remodeling of the fibrotic tissue. The onset of this process is likely caused by multiple mechanisms.[8] Specifically, fibroblast proliferation may be mediated by the transition of epithelial–to-mesenchymal cells, invasion of fibrocytes, or expansion of fibroblasts.[7]

Fibrosis is caused by both the innate and adaptive immune systems. Key innate immune cells involved in IPF include neutrophils, monocytes, and fibrocytes, which serve as precursors for fibroblasts. Meanwhile, the T-helper 2 inflammatory response and type 2 cytokines are part of the adaptive immunity responsible for IPF pathogenesis. Together, these processes increase pro-fibrotic factors such as interleukins (IL) 9 and 13, as well as transforming growth factor (TGF)-β. Dendritic cells also help propagate ongoing inflammation.[8] In addition, inflammation is believed to trigger the activation of alveolar epithelial cells, ultimately leading to the accumulation of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts, thereby promoting excessive extracellular matrix deposition.[9]

The initial insults for inflammation are often related to exposure to cigarette smoke and air pollution. Aging is a primary risk factor for IPF, as with aging, the supply of protective stem cells and pericytes becomes depleted, likely making individuals more susceptible to fibroblast activation and proliferation.[9] Furthermore, several recent studies have reported an association between thyroid dysfunction and fibrosis in various organs, including the lungs.[10] This association indicates a potential role in the pathogenesis of IPF and the development of chronic fibrosis.

Genetic Mutations

IPF involves several genes crucial in lung development and the response to environmental injury, including WNT, TGF, Notch, and sonic hedgehog (SHH). In addition, genes involved in the inflammatory process are also involved, and some of these include the Toll-interacting protein (TOLLIP) and the inhibitory protein of the Toll-like receptor signaling pathway.[8][9]

Although most cases of IPF are idiopathic, some genetic factors that contribute to familial cases have been identified. Mutations in the telomerase genes (such as TERT), surfactant genes (such as SFTPA2), and mucin genes (such as MUC5B) have been known to lead to pulmonary fibrosis. Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome is another rare autosomal recessive condition with defects in lysosome-related organelles that lead to albinism, platelet defects, and pulmonary fibrosis in many of the affected individuals (see Image. Putative Mechanisms of IPF).[11][12]

Epidemiology

IPF usually presents after the fifth or sixth decade of life and is more prevalent in older individuals. Research studies indicate a higher prevalence of IPF in males compared to females.[13] In Europe and North America, estimated IPF prevalence rates range from 0.33 to 2.51 and 2.40 to 2.98 per 10,000 people, respectively.[13] Data from a comprehensive database in the United States revealed a standardized incidence of 14.6 cases per 100,000 person-years, with a prevalence of 58.7 cases per 100,000 individuals during the study period.[14]

The prevalence of IPF typically rises with age, with the majority of patients aged 50 or older and up to 85% being more than the age of 70.[15] However, the familial type of IPF tends to occur at a younger age, although it is much less common, accounting for only 3.7% of cases. The reported incidence of IPF ranges between 2.3 and 5.3 cases per 100,000 people per year.[16]

Pathophysiology

Environmental factors such as smoking, chronic aspiration, or respiratory infections, combined with advancing age, often result in respiratory alveolar epithelial injury and are the likely driving factors for the pathogenesis of IPF.[17] Epithelial injury triggers the activation of fibroblasts and disrupts the normal repair process of the alveolar epithelium. Consequently, this dysregulated repair process leads to increased matrix deposition in the lung interstitium and scarring, ultimately destroying lung architecture and the development of pulmonary fibrosis.[12] The destruction of lung architecture impairs gas exchange and progresses to hypoxic respiratory failure—a hallmark of advanced disease.

About 70% to 80% of patients with IPF have a history of smoking, explaining why around 30% also present with concurrent emphysema. This subgroup of patients with both IPF and emphysema exhibits a distinct PFT profile. Specifically, they typically demonstrate relatively preserved total lung capacity and forced vital capacity (FVC), yet significantly decreased diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLCO). This profile is likely attributed to the combined effects of parenchymal fibrosis and destruction associated with both conditions.[18] As pulmonary hypertension and obstructive sleep apnea are prevalent among patients with IPF,[19] screening for these comorbidities is essential in patients. Even mild pulmonary hypertension is a poor prognostic indicator.[9][18][20]

IPF is also highly linked to coronary artery disease (CAD). In a study evaluating lung transplant candidates for CAD as part of the transplant work-up, 29% of those with IPF were found to have significant CAD, compared to only 10% of those with emphysema, despite a higher proportion of heavy smokers in the emphysema group.[9][21] The prevalence of CAD in patients with IPF is estimated at 4% to 25%, and patients with IPF have a 3-fold increased risk of acute coronary syndrome compared to patients without IPF.[18]

Patients with IPF have a significantly higher risk of venous thromboembolism compared to those without the condition. Longitudinal analysis indicates that the risk of venous thromboembolism in IPF patients is 3- to 6-fold higher than in individuals without IPF.[18][22] Notably, malignancy, particularly lung cancer, is a significant risk factor for venous thromboembolism, and patients with IPF face a 5-fold increased risk of developing lung cancer.[9][18]

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a common comorbidity in patients with IPF. Although many individuals may have clinically silent GERD, estimates suggest that 30% to 50% of those with IPF also experience this condition. In addition, it is hypothesized that GERD contributes to the pathology of IPF through chronic microaspiration. Trials have been conducted to explore the use of GERD therapy in slowing the progression of IPF, but the results are inconclusive.[18][23][24] Additionally, hiatal hernia is common in IPF patients, and surgical intervention for this condition has shown success in individuals awaiting lung transplants.[23][25]

Osteoporosis is common in patients with IPF, even in the absence of steroid use, and is closely associated with FVC and DLCO.[9] Low levels of Vitamin D are likely contributing factors to this phenomenon.

Hypothyroidism is also more common in patients with IPF than in the general population, possibly related to increased underlying autoimmunity. Evidence suggests that this comorbidity serves as a poor prognostic indicator, underscoring the importance of screening all IPF patients for this highly treatable condition.[9][18][26] Moreover, the association between low thyroid hormones and pulmonary fibrosis may carry therapeutic implications.

Anxiety and depression are common among patients with IPF. Anxiety levels often correlate with the degree of hypoxia experienced by the patient, while depression may be associated with the duration of diagnosis and overall quality of life.[9][18]

Histopathology

Histopathological confirmation for IPF may not always be necessary, but it should be considered if there are confounding factors, including cases where imaging shows an atypical UIP pattern (described below) or when there is suspicion of connective tissue disease. Bronchoscopic biopsy yields are typically low as the pathologic changes start subpleurally, and it is primarily useful for excluding other processes. Although bronchoscopic cryo-biopsies have been used more recently for pathologic diagnosis, surgical lung biopsy remains the gold standard when a biopsy is warranted.[27] However, in patients with advanced disease and respiratory failure, the risks associated with lung biopsy may be significant.

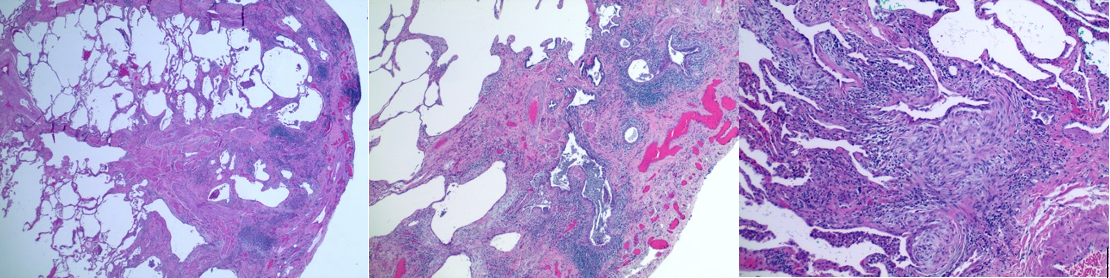

The histology of IPF typically appears nonspecific, showing heterogeneous zones encompassing both normal and affected lung tissue. Interstitial inflammation, honeycomb changes, and fibrosis are commonly observed, although these alterations may also be present in other forms of advanced lung disease.

To establish a histological diagnosis of IPF, the following criteria should be met:[28]

- Presence of foci of fibroblasts

- Evidence of honeycombing or disruption of lung architecture

- Patchy involvement of the lung by fibrosis

- The absence of other features suggests an alternative diagnosis

IPF typically conforms to the pattern of UIP. Macroscopically, interstitial fibrosis appears in a patchwork pattern, with scarred lung areas juxtaposed with regions of normal lung architecture. Fibrosis is evident in the subpleural and periseptal areas, extending into the peribronchial parenchyma. Distortion of lung architecture due to scarring is a hallmark feature of UIP. Additionally, UIP is characterized by "honeycomb" changes, which consist of clusters of dilated, mucin-filled epithelial-lined airspaces set against a fibrotic background. Microscopically visible honeycomb changes are referred to as "microscopic honeycomb changes." Features such as granulomas or giant cells indicative of alternative diagnoses should be absent (see Image. Histopathology of UIP in IPF).[29]

History and Physical

The typical age range for the onset of IPF in individuals is 60 and older. However, younger ages are more common in cases of familial IPF. Hence, obtaining a family history of premature gray hair, other signs of premature aging, and early-onset familial IPF should be a priority during clinical evaluation.[30][31][32] In addition, a thorough history should be taken to inquire about exposure to inhaled dust, metals, asbestos, mold, or birds, as these may be relevant for excluding other ILDs.

The most common presenting symptoms of IPF include dyspnea on exertion and cough, often accompanied by fatigue. Diagnosis is frequently delayed, with many patients not receiving a diagnosis until more than a year after symptom onset. Given the nonspecific nature of symptoms and the idiopathic nature of the disease, it is essential to rule out other conditions before diagnosis.

In evaluating patients for IPF, it is crucial to obtain a thorough medication and drug history, paying particular attention to medications associated with pulmonary toxicity, such as amiodarone and bleomycin. Additionally, assessing patients for symptoms suggestive of rheumatic diseases is important, including joint pain or inflammation, digital ulcers, dry eyes and mouth, fatigue, fever, hair loss, muscle weakness or pain, sensitivity to light, Raynaud phenomenon, skin thickening, and small red spots on the skin. Furthermore, other autoimmune-related disorders such as scleroderma, Sjögren disease, or polymyositis/dermatomyositis should also be considered and evaluated, as these conditions can manifest with ILD. The cough associated with IPF is typically dry and nonproductive.

During the physical examination, attention should be given to assessing lung involvement, determining the extent and severity of the disease, and excluding other potential diagnoses. Classic pulmonary findings typically include fine bibasilar “velcro” crackles heard during inspiration. Clubbing of the fingers may also be present. To exclude autoimmune conditions, it is important to evaluate for signs such as skin rashes, joint swelling, sclerodactyly, Raynaud phenomenon, and muscle weakness. In advanced cases of IPF, patients may demonstrate exercise intolerance with minimal exertion or even exhibit resting hypoxemia.[33]

Evaluation

The diagnosis of IPF is primarily clinical, including identifying potential risk factors such as exposure to inhalation pollutants and manifestations of connective tissue diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, rashes, or skin manifestations. However, various evaluations can assist in confirming the diagnosis.

Laboratory and Pulmonary Function Testing

PFTs should be performed to assess for restrictive lung disease, which is characterized by decreased lung volumes (particularly decreased FVC, total lung capacity, and functional residual capacity) and decreased diffusion capacity. Other potential causes of restrictive ventilatory defects include chest wall abnormalities (eg, kyphoscoliosis), obesity (usually resulting in an isolated reduction in expiratory reserve volume (ERV)), or neuromuscular conditions (presenting with reduced TLC and VC but preserved RV).[34]

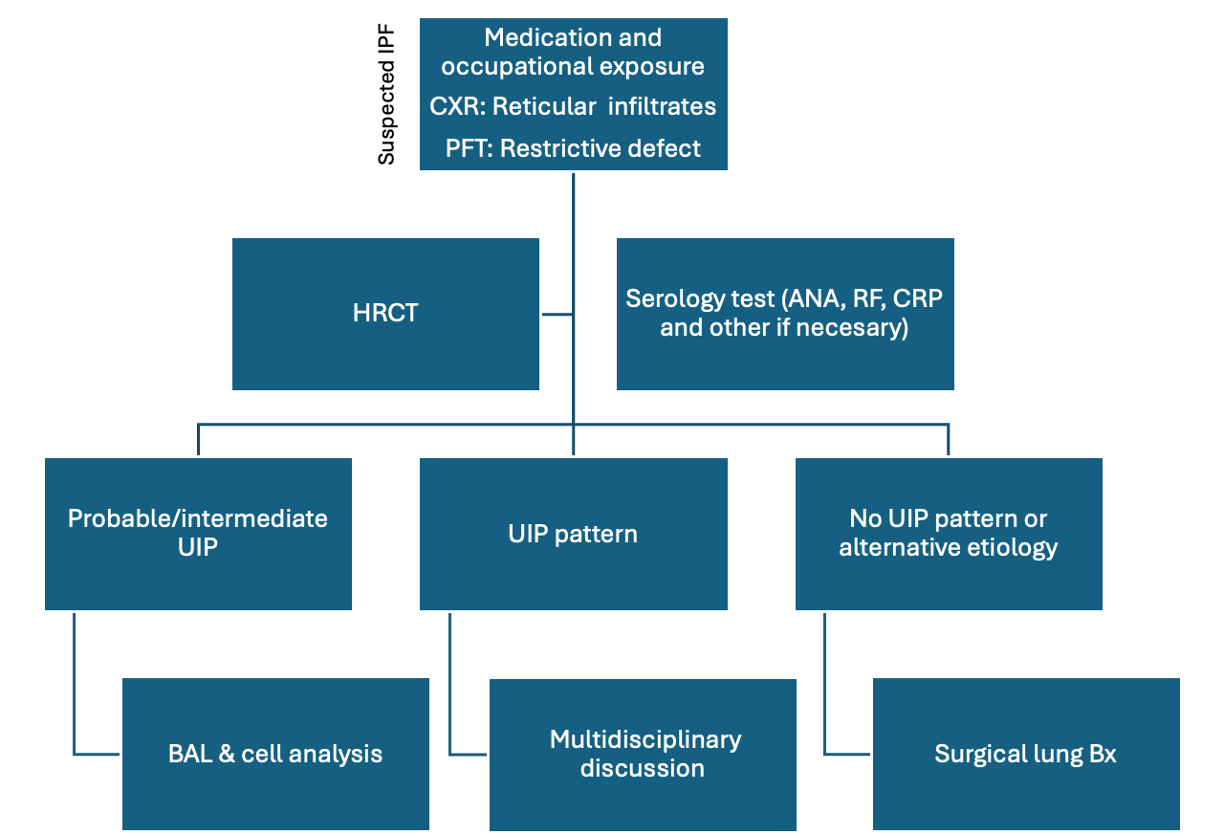

When IPF is suspected, laboratory tests should be performed to exclude autoimmune disease. Commonly indicated tests include antinuclear antibodies and rheumatoid factors. However, if autoimmune disease is highly suspected, additional tests such as antisynthetase antibodies, aldolase, Sjögren, and scleroderma antibodies should also be considered (see Image. Diagnostic Algorithm for Evaluating Suspected IPF).[5][35][36] Individuals diagnosed with short telomere syndrome should be screened for bone marrow and liver dysfunction, and at-risk family members may necessitate telomere length analysis for screening purposes.[37]

Imaging Techniques

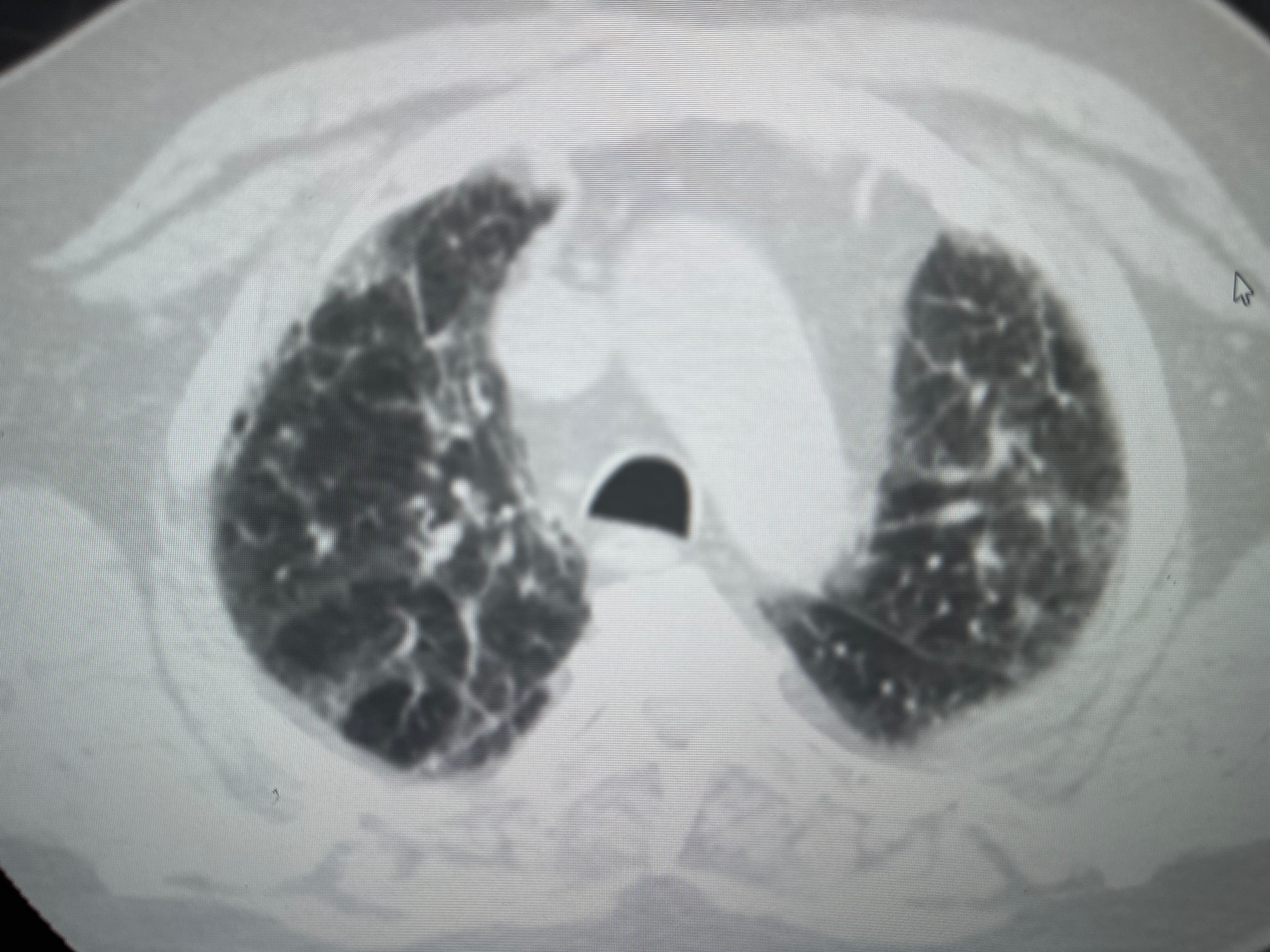

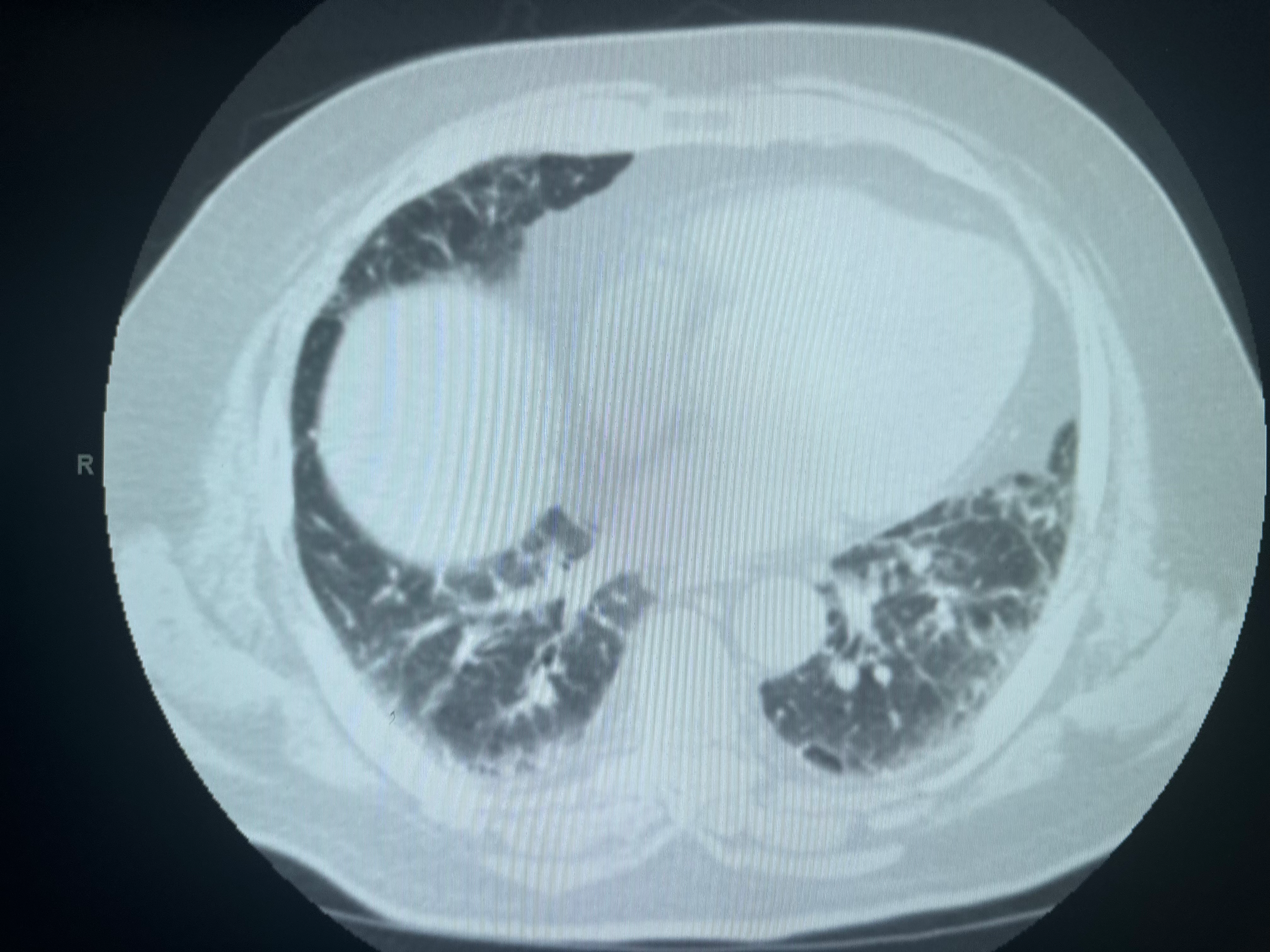

Although chest imaging is essential for diagnosis, chest x-rays lack the details necessary to confirm IPF. HRCT of the chest should be performed with axial cuts of 1.5 mm or less and acquired at 10 mm intervals for the diagnosis of ILD and IPF.[5] The characteristic feature of HRCT is a UIP pattern, which, on imaging, is characterized by bilateral subpleural basal predominant honeycombing or traction bronchiectasis or bronchiectasis (see Image. Radiological Characteristics of CT Patterns for Suspected UIP). Peripheral reticular opacities are usually most notable in the lower lobes. Ground-glass opacities and consolidation are atypical for a UIP pattern and, when present on imaging, should lead to suspicion for conditions other than IPF (see Image. CT Patterns of Probable UIP).

Given the high incidence of CAD in IPF, a coronary artery calcification score may also be warranted. Low-dose CT protocols have been developed for patients requiring repeated imaging, such as those with previously diagnosed ILD, or to assess the presence or progression of lung nodules. This requires imaging the lung at intervals thinner than 10 mm (usually 1-2 mm) to identify small nodules or structural changes while exposing the lung to the least amount of radiation.[38]

The American Thoracic Society guidelines recommend considering surgical lung biopsy if the diagnosis of IPF cannot be confirmed through noninvasive methods, especially when clinical and radiological findings are incongruent with UIP, unless the patient is at high risk for complications.[39] Transbronchial biopsy is avoided due to the small tissue size to microscopically characterize the lung tissue and the peripheral nature of the disease. However, it may help exclude alternative diagnoses such as sarcoidosis or infection. A biopsy should be performed either by thoracotomy or a minimally invasive approach, such as video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery, to obtain adequate tissue to make an accurate diagnosis.[5] Peri-procedural respiratory infections are the most common complication (approximately 6.5%), with a surgical lung biopsy mortality rate estimated at 1.7%. Other potential complications include ILD exacerbation, bleeding, prolonged air leak, neuropathic pain, and delayed wound healing (less than 5%).[5]

The suitability of transbronchial lung cryobiopsy (TBLC) for each patient may vary. Recently, the American Thoracic Society guidelines provided recommended criteria to guide when a patient is suitable for TBLC or surgical lung biopsy. Patients with severe lung function derangement, such as FVC less than 50% predicted, DlCO less than 35%, moderate-to-severe pulmonary hypertension (estimated systolic pulmonary arterial pressure >40 mm Hg), uncorrectable bleeding risk, or significant hypoxemia (PaO2 <55-60 mm Hg) are at a higher risk of adverse outcomes and are considered relative contraindications.[40]

A study suggested that TBLC could be a viable option for certain patients at a higher risk for major complications, especially when performed at centers with a higher volume of cases. A study involving 699 patients who underwent TBLC revealed that both the pathological and final multidisciplinary diagnostic yields were lower in individuals with FVC lower than 50% and/or a DLCO less than 35%. However, no statistically significant differences in complication rates were observed between the 2 groups.[41] The utility of bronchoalveolar lavage in suspected IPF falls within the intermediate probability of UIP clinically and radiological when other alternative causes are not ruled out and require a cell analysis to narrow down the differential diagnosis.[5]

Multidisciplinary Discussion

The multidisciplinary team's discussion involves interactions among radiologists, pathologists, and pulmonologists, with rheumatologists when needed, to improve the diagnostic agreement for IPF.[42] Multidisciplinary discussions enhance diagnostic accuracy and serve a critical role in the detection of this condition. When the outcomes of clinical evaluation, laboratory testing, and HRCT do not lead to a confident diagnosis of IPF after the MMD, a lung biopsy may be necessary.

Treatment / Management

Previous research has shown that patients in advanced stages of IPF experience a more rapid decline in lung function despite receiving treatment. As a result, it is crucial to diagnose IPF in its early stages, where treatment may be more effective in slowing the progression of the disease.[43]

Baseline Assessment and Monitoring

PFTs are recommended every 3 to 6 months, which should be performed based on symptoms and the disease's progression. However, serial chest imaging may not always be necessary. Various tools, such as the GAP (gender, age, and physiology) score, assign points based on gender, age, FVC, and diffusing capacity or transfer factor of the lung for carbon monoxide to assess long-term prognosis. A higher GAP score indicates worse mortality. This scoring system is particularly valuable when evaluating patients for lung transplant referrals.[44][45][46] Additionally, objective assessment of functional status and screening for hypoxic respiratory failure is essential. The 6-minute walk test is commonly used in ILD specialty centers to achieve these goals.[47](A1)

Supportive Treatments

Recommended supportive measures include tobacco cessation, oxygen supplementation, and pulmonary rehabilitation. Although supplemental oxygen is commonly advised for severe ILD cases, such as IPF, limited data exist that can guide its use in this patient population. Studies evaluating supplemental oxygen in ILD patients experiencing exertional hypoxemia are lacking.[48] Research on stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients with mild resting hypoxemia or moderate exercise-induced hypoxemia showed no significant impact of supplemental oxygen on functional capacity, quality of life, need for hospitalization, or mortality.[49] (A1)

Numerous studies have demonstrated the advantages of pulmonary rehabilitation for individuals with ILD, including IPF. A Cochrane review assessing the efficacy of pulmonary rehabilitation for ILD revealed that although pulmonary rehabilitation resulted in improvements in individuals with ILD, the quality of evidence was deemed low-to-moderate due to concerns regarding study methodology.[50] In a specific study, patients with IPF showed similar completion rates and response levels to pulmonary rehabilitation compared to those with COPD patients who were carefully matched.[51] Additionally, noncompletion and nonresponse to pulmonary rehabilitation in IPF patients were connected to increased mortality from all causes.(A1)

The use of antacid medication and other interventions may offer benefits to patients experiencing symptoms of GERD alongside IPF.[39] Although current evidence does not advocate for using antacid medication and antireflux surgery as treatments for IPF, they may still be beneficial for managing GERD symptoms in these individuals.[39](A1)

Influenza and pneumococcal vaccination are recommended for individuals with IPF.[52] Previously, corticosteroids, immunosuppressants such as azathioprine, and N-acetyl cysteine were utilized, but the current recommendation advises against their use in IPF due to findings from the PANTHER-IPF trial.[53](A1)

Antifibrotic Medications

Antifibrotic medications, including pirfenidone and nintedanib (tyrosine kinase inhibitors), are approved for use in IPF. Studies have shown that both drugs can slow disease progression and potentially reduce all-cause mortality and acute exacerbations.[54] Therefore, initiating therapy early is recommended. Initially, pirfenidone was thought to be effective in slowing the progression of IPF in patients with mild to moderate disease, but recent research suggests benefits even for those with more advanced stages (such as FVC <50% predicted and/or DLCO <35% predicted).[55][56] Both pirfenidone and nintedanib have been demonstrated to be equally effective in slowing the 24-month decrease in FVC and diffusion capacity.[43](A1)

The recommended daily dosage of pirfenidone is 267 mg (1 capsule) taken 3 times daily, with a maximum daily dose of 2403 mg divided into 3 doses. In addition, it is essential to monitor liver function tests regularly while on either drug, including liver and renal function tests. Typically, blood testing should be conducted before initiating therapy and regularly throughout treatment, with recommended intervals being monthly liver function tests for the first 6 months and then every 3 months.[57] Pirfenidone should be used cautiously in patients with impaired renal function, such as those with a creatinine clearance of less than 30 mL/min, and it should be avoided in patients on dialysis.[58] (B3)

The recommended daily dosage of nintedanib is 150 mg twice daily. Nintedanib should be avoided in patients with moderate-to-severe liver impairment.[59] Similar to pirfenidone, liver function and enzymes should be monitored before initiating therapy and regularly throughout treatment, with monthly monitoring recommended for the first 3 to 6 months. Nintedanib has the potential for drug-drug interactions, particularly with medications metabolized by cytochrome P450 enzymes.[59]

The most frequently reported adverse effects associated with nintedanib include diarrhea and weight loss, while those for pirfenidone are rash, photosensitivity, and gastrointestinal discomfort.[43] Gastrointestinal adverse effects are the primary reason for discontinuing both medications.[60] Limited evidence exists regarding the efficacy of medications such as sildenafil in reducing mortality and decreasing acute exacerbations.[61](A1)

Lung transplant

Referral for a lung transplant is recommended early in the course of the disease, particularly for patients experiencing a progressive decline in lung function. Studies have demonstrated survival benefits for patients with IPF who undergo a lung transplant.[62]

Additional Treatments

Acute exacerbations can occur in IPF, leading to a rapid decline in lung function. When suspected, it is crucial to exclude factors like heart failure and consider and promptly treat potential infections and thromboembolic disease. Imaging during acute exacerbations may reveal ground-glass opacities and consolidations.[63] IPF primarily affects the lungs, with no observed involvement of other organs. The disease progression varies among patients, with some remaining stable for years after diagnosis, others experiencing rapid decline, and some having periodic exacerbations that contribute to declining lung function and increased mortality.

Baseline lung function at diagnosis, the presence of comorbidities (especially coexisting emphysema and pulmonary hypertension), smoking history, low body mass index, and older age are associated with a worse prognosis in IPF. Monitoring the disease progression typically involves regular evaluations, usually every 3 to 6 months or more frequently as needed, to assess for worsening symptoms such as dyspnea and oxygenation. This monitoring process includes assessing symptoms such as dyspnea and oxygenation, as well as conducting a 6-minute walk test and PFTs to provide more objective data on the disease's progression.[64] (A1)

Palliative care with a focus on progressive end-stage IPF is highly advised. Studies have demonstrated that palliative care improves symptom management, health-related quality of life, and end-of-life care for individuals with IPF, leading to reduced incidence of critical events, hospitalization, and overall healthcare expenditures.[65] Given the association of mechanical ventilation with poor outcomes, it is essential to address goals of care early in the process.[66] (B2)

Investigational treatments: In recent years, there has been an effort to discover drugs that can prevent or halt the formation of fibrosis and fibroblast. A translational study in mouse models demonstrated that aerosolized T3 thyroid hormone can inhibit lung fibrosis by enhancing mitochondrial function in epithelial cells.[67] Similarly, resmetirom, a thyroid hormone agonist, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as the first treatment for liver fibrosis due to fatty liver disease. This approval suggests a potential role in fibrosis treatment, but further studies in humans with IPF are needed to confirm its effectiveness and safety.[55](A1)

Differential Diagnosis

The following conditions are part of the differential diagnosis for IPF:

- Occupational lung diseases, including pneumoconiosis and asbestosis

- Aspiration pneumonitis

- Bacterial and viral pneumonia

- Farmer's lung and other forms of hypersensitivity pneumonitis

- Fungal infection

- Lung cancer

- Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia

- Sarcoidosis

- Pulmonary edema

- Connective tissue diseases

Prognosis

IPF is a progressive disorder with a median survival time of around 5 years. However, about 20% of patients are estimated to survive without any treatment. The uncertainty regarding the progression of the disease and the severity of the symptoms, along with its poor prognosis, have a profound impact on the quality of life of both patients and their families.[65] Since 2010, IPF survival rates have shown improvement, which may be partly attributed to antifibrotic therapies and earlier diagnosis.[68]

Although the actual survival range for individual patients varies considerably, up to 20% to 25% may live beyond 10 years after diagnosis. Despite this, most patients continue to experience dyspnea and limited exercise tolerance, leading to a poor quality of life. Deaths are most common in winter, even in the absence of lung infections. Many patients develop pulmonary hypertension, increasing their risk of pulmonary embolism and sudden cardiac death. The prognosis tends to be worse for those with severe changes noted on imaging findings and a lack of response to oxygen therapy.[69][70]

Complications

Complications associated with IPF include pulmonary hypertension, thromboembolic disease, adverse effects of medications, superimposed lung infections, acute coronary syndrome, and hypoxic respiratory failure.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Currently, specific recommendations for screening or deterrence of F are not available. However, patients diagnosed with IPF should adhere to the following measures:[5][71][72]

- They should maintain a healthy weight and engage in exercise regularly. Pulmonary rehabilitation can be utilized for formal exercise training.

- They should cease smoking, if applicable.

- They should avoid environmental or occupational exposure that could exacerbate lung disease.

- They should manage acid reflux as needed.

- They should follow up for disease-specific therapies and consider referrals for lung transplants.

- They should ensure vaccinations for influenza, pneumococcus, and COVID-19, as individuals with IPF have reduced lung reserve to tolerate respiratory infections.

Pearls and Other Issues

Navigating the complexities of IPF, a disease with potentially life-limiting symptoms, requires early diagnosis and a multidisciplinary approach.

- Interdisciplinary management often involves collaboration among various specialists, including pulmonologists, chest radiologists, thoracic surgeons, rheumatologists, and pathologists.

- Patients with IPF benefit from referral to an ILD specialty clinic for discussions regarding antifibrotic drug therapies and timely consideration for lung transplant.

- Given the increased risk of CAD and acute coronary syndrome in these patients, cardiac calcification scores or other risk stratification measures should be considered as part of their comprehensive care.

- All patients should undergo screening for obstructive sleep apnea, GERD, and hypothyroidism, with appropriate treatment initiated as necessary.

- Given the progressive nature of lung disease, it is imperative to address advanced care plans and end-of-life issues proactively.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Patients diagnosed with IPF face a high risk of disease progression. Thus, it is crucial to promptly identify and manage IPF to mitigate morbidity and mortality. Providing optimal care for individuals with IPF requires a collaborative approach among healthcare professionals to deliver patient-centered care and enhance overall outcomes. Primary care providers, pulmonologists, ILD experts, emergency medicine physicians, critical care physicians, advanced practitioners, nurses, pharmacists, dieticians, and other health professionals involved in the care of these patients should possess the essential clinical skills and knowledge to diagnose and manage IPF accurately. This includes expertise in recognizing the varied clinical presentations and understanding the intricacies of diagnostic techniques such as HRCT scans and, if necessary, lung biopsies.

Patient and caregiver education regarding triggering factors, medication compliance, smoking cessation, allergen avoidance, and medication adherence is crucial to reduce morbidity associated with IPF. Engaging in physical therapy can aid in preserving lung function and enhancing quality of life. Early referral for a lung transplant and completion of the necessary work-up are essential components of management.

A strategic approach involving evidence-based strategies to optimize treatment plans and minimize adverse effects is equally crucial in managing IPF. Ethical considerations must guide the decision-making process, ensuring informed consent and respecting patient autonomy in treatment choices. Each healthcare professional must know their responsibilities and contribute their unique expertise to the patient's care plan, fostering a multidisciplinary approach. Effective interprofessional communication is paramount, allowing seamless information exchange and collaborative decision-making among the team members.

Care coordination is pivotal in ensuring that the patient's journey from diagnosis to treatment and follow-up is well-managed, minimizing errors and enhancing patient safety. By embracing these principles of skill, strategy, ethics, responsibilities, interprofessional communication, and care coordination, healthcare professionals can deliver patient-centered care, ultimately improving patient outcomes and enhancing team performance in the management of IPF.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Diagnostic Algorithm for Evaluating Suspected IPF. A diagram summarizing the evaluation process for suspected cases of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). Abbreviations: ANA, antinuclear antibodies; BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage; Bx, biopsy; CRP, C-reactive protein; CXR, chest x-ray; HRCT, high-resolution computed tomography scan; PFT, pulmonary function tests; RF, rheumatoid factor; UIP, usual interstitial pneumonia.

Contributed by A Sankari, MD

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Putative Mechanisms of IPF. This diagram illustrates the putative mechanisms underlying idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). The image highlights the significant interaction among genetic factors (such as gene mutations), environmental exposures (such as smoking and viruses), and aging-related mechanisms (such as genetic instability, abnormal shortening of telomeres, and mitochondrial dysfunction). These interactions lead to aberrant phenotypic and functional changes in the airway and alveolar epithelium, contributing to the development and progression of IPF.

Contributed by A Sankari, MD

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Radiological Characteristics of CT Patterns for Suspected UIP. This image shows radiological examples from a computed tomography (CT) scan of a patient's chest, suggesting the characteristic CT pattern of probable usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP). Notable features include mid and lower lung-predominant subpleural reticulation and associated ground-glass opacities or atelectasis observed in both upper and lower lobes.

Contributed by A Sankari, MD

(Click Image to Enlarge)

CT Patterns of Probable UIP. This image displays the computed tomography (CT) pattern characteristic of probable usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP), emphasizing lower lung-predominant subpleural reticulation accompanied by associated ground-glass opacities or atelectasis.

Contributed by A Sankari, MD

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Histopathology of UIP in IPF. This image showcases typical features of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), characterized by usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining at magnifications of ×2, ×4, and ×10. The classic "honeycombing" changes of lung architecture accompanied by inflammatory cell infiltrate and fibroblast predominance (blue) are also noted.

Contributed by A Sankari, MD

References

Martinez FJ, Collard HR, Pardo A, Raghu G, Richeldi L, Selman M, Swigris JJ, Taniguchi H, Wells AU. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Nature reviews. Disease primers. 2017 Oct 20:3():17074. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.74. Epub 2017 Oct 20 [PubMed PMID: 29052582]

Njock MS, Guiot J, Henket MA, Nivelles O, Thiry M, Dequiedt F, Corhay JL, Louis RE, Struman I. Sputum exosomes: promising biomarkers for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Thorax. 2019 Mar:74(3):309-312. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2018-211897. Epub 2018 Sep 22 [PubMed PMID: 30244194]

Walsh SLF, Calandriello L, Silva M, Sverzellati N. Deep learning for classifying fibrotic lung disease on high-resolution computed tomography: a case-cohort study. The Lancet. Respiratory medicine. 2018 Nov:6(11):837-845. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30286-8. Epub 2018 Sep 16 [PubMed PMID: 30232049]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWells AU. Efficacy data in treatment extension studies of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: interpret with caution. The Lancet. Respiratory medicine. 2019 Jan:7(1):7-8. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30385-0. Epub 2018 Sep 14 [PubMed PMID: 30224324]

Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Myers JL, Richeldi L, Ryerson CJ, Lederer DJ, Behr J, Cottin V, Danoff SK, Morell F, Flaherty KR, Wells A, Martinez FJ, Azuma A, Bice TJ, Bouros D, Brown KK, Collard HR, Duggal A, Galvin L, Inoue Y, Jenkins RG, Johkoh T, Kazerooni EA, Kitaichi M, Knight SL, Mansour G, Nicholson AG, Pipavath SNJ, Buendía-Roldán I, Selman M, Travis WD, Walsh S, Wilson KC, American Thoracic Society, European Respiratory Society, Japanese Respiratory Society, and Latin American Thoracic Society. Diagnosis of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2018 Sep 1:198(5):e44-e68. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201807-1255ST. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30168753]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMei Q, Liu Z, Zuo H, Yang Z, Qu J. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: An Update on Pathogenesis. Frontiers in pharmacology. 2021:12():797292. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.797292. Epub 2022 Jan 19 [PubMed PMID: 35126134]

Günther A, Korfei M, Mahavadi P, von der Beck D, Ruppert C, Markart P. Unravelling the progressive pathophysiology of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. European respiratory review : an official journal of the European Respiratory Society. 2012 Jun 1:21(124):152-60. doi: 10.1183/09059180.00001012. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22654088]

Heukels P, Moor CC, von der Thüsen JH, Wijsenbeek MS, Kool M. Inflammation and immunity in IPF pathogenesis and treatment. Respiratory medicine. 2019 Feb:147():79-91. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2018.12.015. Epub 2019 Jan 9 [PubMed PMID: 30704705]

Luppi F, Kalluri M, Faverio P, Kreuter M, Ferrara G. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis beyond the lung: understanding disease mechanisms to improve diagnosis and management. Respiratory research. 2021 Apr 17:22(1):109. doi: 10.1186/s12931-021-01711-1. Epub 2021 Apr 17 [PubMed PMID: 33865386]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBano A, Chaker L, Muka T, Mattace-Raso FUS, Bally L, Franco OH, Peeters RP, Razvi S. Thyroid Function and the Risk of Fibrosis of the Liver, Heart, and Lung in Humans: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Thyroid : official journal of the American Thyroid Association. 2020 Jun:30(6):806-820. doi: 10.1089/thy.2019.0572. Epub 2020 Feb 13 [PubMed PMID: 31910097]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceZhang L, Wang Y, Wu G, Xiong W, Gu W, Wang CY. Macrophages: friend or foe in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis? Respiratory research. 2018 Sep 6:19(1):170. doi: 10.1186/s12931-018-0864-2. Epub 2018 Sep 6 [PubMed PMID: 30189872]

Shioya M, Otsuka M, Yamada G, Umeda Y, Ikeda K, Nishikiori H, Kuronuma K, Chiba H, Takahashi H. Poorer Prognosis of Idiopathic Pleuroparenchymal Fibroelastosis Compared with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis in Advanced Stage. Canadian respiratory journal. 2018:2018():6043053. doi: 10.1155/2018/6043053. Epub 2018 Aug 13 [PubMed PMID: 30186537]

Hutchinson J, Fogarty A, Hubbard R, McKeever T. Global incidence and mortality of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a systematic review. The European respiratory journal. 2015 Sep:46(3):795-806. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00185114. Epub 2015 May 14 [PubMed PMID: 25976683]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceEsposito DB, Lanes S, Donneyong M, Holick CN, Lasky JA, Lederer D, Nathan SD, O'Quinn S, Parker J, Tran TN. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis in United States Automated Claims. Incidence, Prevalence, and Algorithm Validation. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2015 Nov 15:192(10):1200-7. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201504-0818OC. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26241562]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceOlson AL, Gifford AH, Inase N, Fernández Pérez ER, Suda T. The epidemiology of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and interstitial lung diseases at risk of a progressive-fibrosing phenotype. European respiratory review : an official journal of the European Respiratory Society. 2018 Dec 31:27(150):. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0077-2018. Epub 2018 Dec 21 [PubMed PMID: 30578336]

Harari S, Madotto F, Caminati A, Conti S, Cesana G. Epidemiology of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis in Northern Italy. PloS one. 2016:11(2):e0147072. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147072. Epub 2016 Feb 3 [PubMed PMID: 26841042]

Mostafaei S, Sayad B, Azar MEF, Doroudian M, Hadifar S, Behrouzi A, Riahi P, Hussen BM, Bayat B, Nahand JS, Moghoofei M. The role of viral and bacterial infections in the pathogenesis of IPF: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Respiratory research. 2021 Feb 12:22(1):53. doi: 10.1186/s12931-021-01650-x. Epub 2021 Feb 12 [PubMed PMID: 33579274]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceOldham JM, Collard HR. Comorbid Conditions in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: Recognition and Management. Frontiers in medicine. 2017:4():123. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2017.00123. Epub 2017 Aug 2 [PubMed PMID: 28824912]

Papadogiannis G, Bouloukaki I, Mermigkis C, Michelakis S, Ermidou C, Mauroudi E, Moniaki V, Tzanakis N, Antoniou KM, Schiza SE. Patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis with and without obstructive sleep apnea: differences in clinical characteristics, clinical outcomes, and the effect of PAP treatment. Journal of clinical sleep medicine : JCSM : official publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. 2021 Mar 1:17(3):533-544. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.8932. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33108270]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKimura M, Taniguchi H, Kondoh Y, Kimura T, Kataoka K, Nishiyama O, Aso H, Sakamoto K, Hasegawa Y. Pulmonary hypertension as a prognostic indicator at the initial evaluation in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respiration; international review of thoracic diseases. 2013:85(6):456-63. doi: 10.1159/000345221. Epub 2012 Dec 19 [PubMed PMID: 23257350]

Izbicki G, Ben-Dor I, Shitrit D, Bendayan D, Aldrich TK, Kornowski R, Kramer MR. The prevalence of coronary artery disease in end-stage pulmonary disease: is pulmonary fibrosis a risk factor? Respiratory medicine. 2009 Sep:103(9):1346-9. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2009.03.012. Epub 2009 Apr 11 [PubMed PMID: 19362458]

Lee JH, Lee HH, Park HJ, Kim S, Kim YJ, Lee JS, Kim HC. Venous thromboembolism in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, based on nationwide claim data. Therapeutic advances in respiratory disease. 2023 Jan-Dec:17():17534666231155772. doi: 10.1177/17534666231155772. Epub [PubMed PMID: 36846942]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLee JS, Ryu JH, Elicker BM, Lydell CP, Jones KD, Wolters PJ, King TE Jr, Collard HR. Gastroesophageal reflux therapy is associated with longer survival in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2011 Dec 15:184(12):1390-4. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201101-0138OC. Epub 2011 Jun 23 [PubMed PMID: 21700909]

Kreuter M, Wuyts W, Renzoni E, Koschel D, Maher TM, Kolb M, Weycker D, Spagnolo P, Kirchgaessler KU, Herth FJ, Costabel U. Antacid therapy and disease outcomes in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a pooled analysis. The Lancet. Respiratory medicine. 2016 May:4(5):381-9. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(16)00067-9. Epub 2016 Mar 31 [PubMed PMID: 27050871]

Linden PA, Gilbert RJ, Yeap BY, Boyle K, Deykin A, Jaklitsch MT, Sugarbaker DJ, Bueno R. Laparoscopic fundoplication in patients with end-stage lung disease awaiting transplantation. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2006 Feb:131(2):438-46 [PubMed PMID: 16434276]

Oldham JM, Kumar D, Lee C, Patel SB, Takahashi-Manns S, Demchuk C, Strek ME, Noth I. Thyroid Disease Is Prevalent and Predicts Survival in Patients With Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Chest. 2015 Sep:148(3):692-700. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-2714. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25811599]

Romagnoli M, Colby TV, Berthet JP, Gamez AS, Mallet JP, Serre I, Cancellieri A, Cavazza A, Solovei L, Dell'Amore A, Dolci G, Guerrieri A, Reynaud P, Bommart S, Zompatori M, Dalpiaz G, Nava S, Trisolini R, Suehs CM, Vachier I, Molinari N, Bourdin A. Poor Concordance between Sequential Transbronchial Lung Cryobiopsy and Surgical Lung Biopsy in the Diagnosis of Diffuse Interstitial Lung Diseases. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2019 May 15:199(10):1249-1256. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201810-1947OC. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30864813]

Wolters PJ, Collard HR, Jones KD. Pathogenesis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Annual review of pathology. 2014:9():157-79. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-012513-104706. Epub 2013 Sep 13 [PubMed PMID: 24050627]

Mukhopadhyay S. Usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP): a clinically significant pathologic diagnosis. Modern pathology : an official journal of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, Inc. 2022 May:35(5):580-588. doi: 10.1038/s41379-022-01053-3. Epub 2022 Feb 28 [PubMed PMID: 35228663]

Chambers DC, Clarke BE, McGaughran J, Garcia CK. Lung fibrosis, premature graying, and macrocytosis. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2012 Sep 1:186(5):e8-9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201112-2175IM. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22942352]

Dai J, Cai H, Zhuang Y, Wu Y, Min H, Li J, Shi Y, Gao Q, Yi L. Telomerase gene mutations and telomere length shortening in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in a Chinese population. Respirology (Carlton, Vic.). 2015 Jan:20(1):122-8. doi: 10.1111/resp.12422. Epub 2014 Oct 23 [PubMed PMID: 25346280]

Wytrychowski K, Hans-Wytrychowska A, Nowakowska B. Familial idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 2013:788():363-7. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-6627-3_49. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23835999]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGuenther A, Krauss E, Tello S, Wagner J, Paul B, Kuhn S, Maurer O, Heinemann S, Costabel U, Barbero MAN, Müller V, Bonniaud P, Vancheri C, Wells A, Vasakova M, Pesci A, Sofia M, Klepetko W, Seeger W, Drakopanagiotakis F, Crestani B. The European IPF registry (eurIPFreg): baseline characteristics and survival of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respiratory research. 2018 Jul 28:19(1):141. doi: 10.1186/s12931-018-0845-5. Epub 2018 Jul 28 [PubMed PMID: 30055613]

Ponce MC, Sankari A, Sharma S. Pulmonary Function Tests. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29493964]

Nakatsuka Y, Handa T, Kokosi M, Tanizawa K, Puglisi S, Jacob J, Sokai A, Ikezoe K, Kanatani KT, Kubo T, Tomioka H, Taguchi Y, Nagai S, Chin K, Mishima M, Wells AU, Hirai T. The Clinical Significance of Body Weight Loss in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Patients. Respiration; international review of thoracic diseases. 2018:96(4):338-347. doi: 10.1159/000490355. Epub 2018 Aug 21 [PubMed PMID: 30130749]

Walsh SLF. Imaging biomarkers and staging in IPF. Current opinion in pulmonary medicine. 2018 Sep:24(5):445-452. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000507. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30015679]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMangaonkar AA, Patnaik MM. Short Telomere Syndromes in Clinical Practice: Bridging Bench and Bedside. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 2018 Jul:93(7):904-916. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.03.020. Epub 2018 May 24 [PubMed PMID: 29804726]

National Lung Screening Trial Research Team, Aberle DR, Adams AM, Berg CD, Black WC, Clapp JD, Fagerstrom RM, Gareen IF, Gatsonis C, Marcus PM, Sicks JD. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. The New England journal of medicine. 2011 Aug 4:365(5):395-409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873. Epub 2011 Jun 29 [PubMed PMID: 21714641]

Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Richeldi L, Thomson CC, Inoue Y, Johkoh T, Kreuter M, Lynch DA, Maher TM, Martinez FJ, Molina-Molina M, Myers JL, Nicholson AG, Ryerson CJ, Strek ME, Troy LK, Wijsenbeek M, Mammen MJ, Hossain T, Bissell BD, Herman DD, Hon SM, Kheir F, Khor YH, Macrea M, Antoniou KM, Bouros D, Buendia-Roldan I, Caro F, Crestani B, Ho L, Morisset J, Olson AL, Podolanczuk A, Poletti V, Selman M, Ewing T, Jones S, Knight SL, Ghazipura M, Wilson KC. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (an Update) and Progressive Pulmonary Fibrosis in Adults: An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2022 May 1:205(9):e18-e47. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202202-0399ST. Epub [PubMed PMID: 35486072]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLentz RJ, Argento AC, Colby TV, Rickman OB, Maldonado F. Transbronchial cryobiopsy for diffuse parenchymal lung disease: a state-of-the-art review of procedural techniques, current evidence, and future challenges. Journal of thoracic disease. 2017 Jul:9(7):2186-2203. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2017.06.96. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28840020]

Ravaglia C, Wells AU, Tomassetti S, Gurioli C, Gurioli C, Dubini A, Cavazza A, Colby TV, Piciucchi S, Puglisi S, Bosi M, Poletti V. Diagnostic yield and risk/benefit analysis of trans-bronchial lung cryobiopsy in diffuse parenchymal lung diseases: a large cohort of 699 patients. BMC pulmonary medicine. 2019 Jan 16:19(1):16. doi: 10.1186/s12890-019-0780-3. Epub 2019 Jan 16 [PubMed PMID: 30651103]

Furini F, Carnevale A, Casoni GL, Guerrini G, Cavagna L, Govoni M, Sciré CA. The Role of the Multidisciplinary Evaluation of Interstitial Lung Diseases: Systematic Literature Review of the Current Evidence and Future Perspectives. Frontiers in medicine. 2019:6():246. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2019.00246. Epub 2019 Oct 31 [PubMed PMID: 31750308]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCerri S, Monari M, Guerrieri A, Donatelli P, Bassi I, Garuti M, Luppi F, Betti S, Bandelli G, Carpano M, Bacchi Reggiani ML, Tonelli R, Clini E, Nava S. Real-life comparison of pirfenidone and nintedanib in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A 24-month assessment. Respiratory medicine. 2019 Nov:159():105803. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2019.105803. Epub 2019 Oct 18 [PubMed PMID: 31670147]

Homma S, Bando M, Azuma A, Sakamoto S, Sugino K, Ishii Y, Izumi S, Inase N, Inoue Y, Ebina M, Ogura T, Kishi K, Kishaba T, Kido T, Gemma A, Goto Y, Sasaki S, Johkoh T, Suda T, Takahashi K, Takahashi H, Taguchi Y, Date H, Taniguchi H, Nakayama T, Nishioka Y, Hasegawa Y, Hattori N, Fukuoka J, Miyamoto A, Mukae H, Yokoyama A, Yoshino I, Watanabe K, Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, the Study Group on Diffuse Pulmonary Disorders, Scientific Research/Research on Intractable Diseases, and Japanese Respiratory Society. Japanese guideline for the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respiratory investigation. 2018 Jul:56(4):268-291. doi: 10.1016/j.resinv.2018.03.003. Epub 2018 Jul 3 [PubMed PMID: 29980444]

Cheng L, Tan B, Yin Y, Wang S, Jia L, Warner G, Jia G, Jiang W. Short- and long-term effects of pulmonary rehabilitation for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical rehabilitation. 2018 Oct:32(10):1299-1307. doi: 10.1177/0269215518779122. Epub 2018 May 30 [PubMed PMID: 29843523]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceTolle LB, Southern BD, Culver DA, Horowitz JC. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: What primary care physicians need to know. Cleveland Clinic journal of medicine. 2018 May:85(5):377-386. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.85a.17018. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29733782]

Harari S, Wells AU, Wuyts WA, Nathan SD, Kirchgaessler KU, Bengus M, Behr J. The 6-min walk test as a primary end-point in interstitial lung disease. European respiratory review : an official journal of the European Respiratory Society. 2022 Sep 30:31(165):. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0087-2022. Epub 2022 Aug 23 [PubMed PMID: 36002171]

Johannson KA, Pendharkar SR, Mathison K, Fell CD, Guenette JA, Kalluri M, Kolb M, Ryerson CJ. Supplemental Oxygen in Interstitial Lung Disease: An Art in Need of Science. Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 2017 Sep:14(9):1373-1377. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201702-137OI. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28644693]

Long-Term Oxygen Treatment Trial Research Group, Albert RK, Au DH, Blackford AL, Casaburi R, Cooper JA Jr, Criner GJ, Diaz P, Fuhlbrigge AL, Gay SE, Kanner RE, MacIntyre N, Martinez FJ, Panos RJ, Piantadosi S, Sciurba F, Shade D, Stibolt T, Stoller JK, Wise R, Yusen RD, Tonascia J, Sternberg AL, Bailey W. A Randomized Trial of Long-Term Oxygen for COPD with Moderate Desaturation. The New England journal of medicine. 2016 Oct 27:375(17):1617-1627 [PubMed PMID: 27783918]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceDowman L, Hill CJ, May A, Holland AE. Pulmonary rehabilitation for interstitial lung disease. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2021 Feb 1:2(2):CD006322. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006322.pub4. Epub 2021 Feb 1 [PubMed PMID: 34559419]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceNolan CM, Polgar O, Schofield SJ, Patel S, Barker RE, Walsh JA, Ingram KA, George PM, Molyneaux PL, Maher TM, Man WD. Pulmonary Rehabilitation in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis and COPD: A Propensity-Matched Real-World Study. Chest. 2022 Mar:161(3):728-737. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2021.10.021. Epub 2021 Oct 23 [PubMed PMID: 34699771]

Marijic P, Schwarzkopf L, Maier W, Trudzinski F, Schwettmann L, Kreuter M. Effects of Influenza Vaccination in Patients with Interstitial Lung Diseases: An Epidemiological Claims Data Analysis. Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 2022 Sep:19(9):1479-1488. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202112-1359OC. Epub [PubMed PMID: 35312465]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceIdiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Clinical Research Network, Raghu G, Anstrom KJ, King TE Jr, Lasky JA, Martinez FJ. Prednisone, azathioprine, and N-acetylcysteine for pulmonary fibrosis. The New England journal of medicine. 2012 May 24:366(21):1968-77. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113354. Epub 2012 May 20 [PubMed PMID: 22607134]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencePetnak T, Lertjitbanjong P, Thongprayoon C, Moua T. Impact of Antifibrotic Therapy on Mortality and Acute Exacerbation in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Chest. 2021 Nov:160(5):1751-1763. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2021.06.049. Epub 2021 Jul 2 [PubMed PMID: 34217681]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHarrison SA, Bedossa P, Guy CD, Schattenberg JM, Loomba R, Taub R, Labriola D, Moussa SE, Neff GW, Rinella ME, Anstee QM, Abdelmalek MF, Younossi Z, Baum SJ, Francque S, Charlton MR, Newsome PN, Lanthier N, Schiefke I, Mangia A, Pericàs JM, Patil R, Sanyal AJ, Noureddin M, Bansal MB, Alkhouri N, Castera L, Rudraraju M, Ratziu V, MAESTRO-NASH Investigators. A Phase 3, Randomized, Controlled Trial of Resmetirom in NASH with Liver Fibrosis. The New England journal of medicine. 2024 Feb 8:390(6):497-509. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2309000. Epub [PubMed PMID: 38324483]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCostabel U, Albera C, Glassberg MK, Lancaster LH, Wuyts WA, Petzinger U, Gilberg F, Kirchgaessler KU, Noble PW. Effect of pirfenidone in patients with more advanced idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respiratory research. 2019 Mar 12:20(1):55. doi: 10.1186/s12931-019-1021-2. Epub 2019 Mar 12 [PubMed PMID: 30866942]

Mandovra NP, Vaidya PJ, Shah RS, Nighojkar AS, Chavhan VB, Lohiya A, Leuppi JD, Leuppi-Taegtmeyer A, Chhajed PN. Factors Affecting Best-Tolerated Dose of Pirfenidone in Patients with Fibrosing Interstitial Lung Disease. Journal of clinical medicine. 2023 Oct 13:12(20):. doi: 10.3390/jcm12206513. Epub 2023 Oct 13 [PubMed PMID: 37892651]

Xaubet A, Serrano-Mollar A, Ancochea J. Pirfenidone for the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Expert opinion on pharmacotherapy. 2014 Feb:15(2):275-81. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2014.867328. Epub 2013 Dec 6 [PubMed PMID: 24308635]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWind S, Schmid U, Freiwald M, Marzin K, Lotz R, Ebner T, Stopfer P, Dallinger C. Clinical Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Nintedanib. Clinical pharmacokinetics. 2019 Sep:58(9):1131-1147. doi: 10.1007/s40262-019-00766-0. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31016670]

Maher TM, Strek ME. Antifibrotic therapy for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: time to treat. Respiratory research. 2019 Sep 6:20(1):205. doi: 10.1186/s12931-019-1161-4. Epub 2019 Sep 6 [PubMed PMID: 31492155]

Pitre T, Khalid MF, Cui S, Zhang MC, Husnudinov R, Mah J, Helmczi W, Su J, Guy B, Scallan C, Jones A, Zeraatkar D. Sildenafil for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pulmonary pharmacology & therapeutics. 2022 Jun:73-74():102128. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2022.102128. Epub 2022 Apr 20 [PubMed PMID: 35452834]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSomogyi V, Chaudhuri N, Torrisi SE, Kahn N, Müller V, Kreuter M. The therapy of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: what is next? European respiratory review : an official journal of the European Respiratory Society. 2019 Sep 30:28(153):. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0021-2019. Epub 2019 Sep 4 [PubMed PMID: 31484664]

Chung JH, Oldham JM, Montner SM, Vij R, Adegunsoye A, Husain AN, Noth I, Lynch DA, Strek ME. CT-Pathologic Correlation of Major Types of Pulmonary Fibrosis: Insights for Revisions to Current Guidelines. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2018 May:210(5):1034-1041. doi: 10.2214/AJR.17.18947. Epub 2018 Mar 16 [PubMed PMID: 29547052]

Raghu G, Rochwerg B, Zhang Y, Garcia CA, Azuma A, Behr J, Brozek JL, Collard HR, Cunningham W, Homma S, Johkoh T, Martinez FJ, Myers J, Protzko SL, Richeldi L, Rind D, Selman M, Theodore A, Wells AU, Hoogsteden H, Schünemann HJ, American Thoracic Society, European Respiratory society, Japanese Respiratory Society, Latin American Thoracic Association. An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline: Treatment of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. An Update of the 2011 Clinical Practice Guideline. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2015 Jul 15:192(2):e3-19. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201506-1063ST. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26177183]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMicco A, Carpentieri E, Di Sorbo A, Chetta A, Del Donno M. Palliative care and end of life management in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Multidisciplinary respiratory medicine. 2023 Jan 17:18():896. doi: 10.4081/mrm.2023.896. Epub 2023 Feb 21 [PubMed PMID: 36909932]

Rush B, Wiskar K, Berger L, Griesdale D. The use of mechanical ventilation in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in the United States: A nationwide retrospective cohort analysis. Respiratory medicine. 2016 Feb:111():72-6. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2015.12.005. Epub 2015 Dec 21 [PubMed PMID: 26733227]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceYu G, Tzouvelekis A, Wang R, Herazo-Maya JD, Ibarra GH, Srivastava A, de Castro JPW, DeIuliis G, Ahangari F, Woolard T, Aurelien N, Arrojo E Drigo R, Gan Y, Graham M, Liu X, Homer RJ, Scanlan TS, Mannam P, Lee PJ, Herzog EL, Bianco AC, Kaminski N. Thyroid hormone inhibits lung fibrosis in mice by improving epithelial mitochondrial function. Nature medicine. 2018 Jan:24(1):39-49. doi: 10.1038/nm.4447. Epub 2017 Dec 4 [PubMed PMID: 29200204]

Zheng Q, Cox IA, Campbell JA, Xia Q, Otahal P, de Graaff B, Corte TJ, Teoh AKY, Walters EH, Palmer AJ. Mortality and survival in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. ERJ open research. 2022 Jan:8(1):. pii: 00591-2021. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00591-2021. Epub 2022 Mar 14 [PubMed PMID: 35295232]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSerajeddini H, Rogliani P, Mura M. Multi-dimensional Assessment of IPF Across a Wide Range of Disease Severity. Lung. 2018 Dec:196(6):707-713. doi: 10.1007/s00408-018-0152-4. Epub 2018 Aug 27 [PubMed PMID: 30151723]

Barratt SL, Creamer A, Hayton C, Chaudhuri N. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF): An Overview. Journal of clinical medicine. 2018 Aug 6:7(8):. doi: 10.3390/jcm7080201. Epub 2018 Aug 6 [PubMed PMID: 30082599]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJeong SO, Uh ST, Park S, Kim HS. Effects of patient satisfaction and confidence on the success of treatment of combined rheumatic disease and interstitial lung disease in a multidisciplinary outpatient clinic. International journal of rheumatic diseases. 2018 Aug:21(8):1600-1608. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.13331. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30146740]

Ahmad K, Nathan SD. Novel management strategies for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Expert review of respiratory medicine. 2018 Oct:12(10):831-842. doi: 10.1080/17476348.2018.1513332. Epub 2018 Aug 30 [PubMed PMID: 30136607]