Introduction

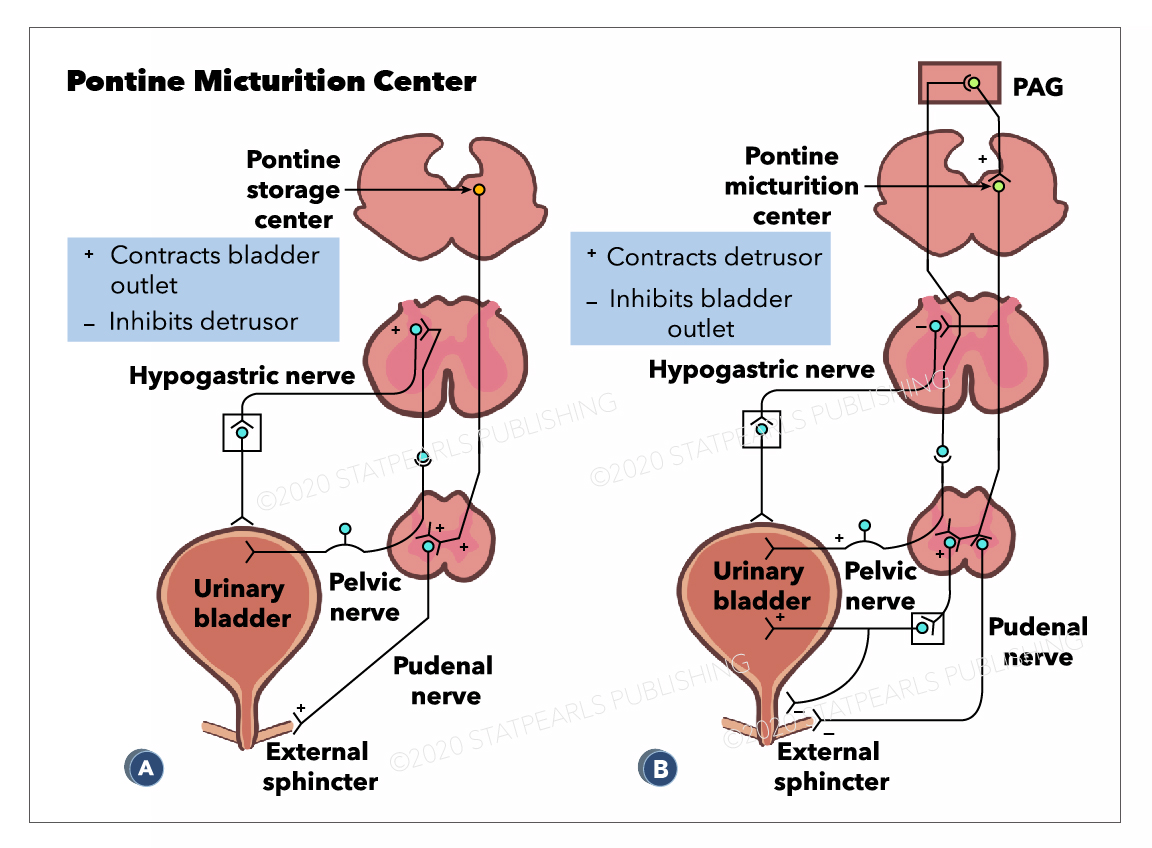

The neural circuitry that controls urination, or micturition, is complex and highly distributed. It involves pathways at various levels of the brain, the spinal cord, and the peripheral nervous system and is under the mediation of multiple neurotransmitters.[1] To fully understand the role that the Pontine Micturition Center (PMC) plays in regulating urination requires a basic understanding of the structures and innervations involved.

The mechanisms of storing and eliminating urine depend on the coordinated activity of the two functional units of the lower urinary tract: the urinary bladder and urinary outlet. The bladders' primary function is storing urine and contracting to void the stored urine. It is comprised mainly of smooth muscle, namely the detrusor muscle. The urinary outlet through which urine passes upon exiting the bladder consists of:

- The bladder neck

- The urethra

- The urethral sphincters

If either of the sphincters contracts, the urethra is blocked, and urine will not flow out.[2]

As a summary of innervation of these structures:

- Sympathetic innervation originates in the thoracic spine and serves to inhibit urination. Sympathetic nerves inhibit the detrusor muscle and activate the internal sphincter to contract.

- Parasympathetic innervation originates in the sacrum and serves to promote urination. Parasympathetic nerves activate the detrusor muscle causing it to contract and relax the internal sphincter.

- Both of these innervations act on the internal sphincter, which is made of smooth muscle and is an extension of the detrusor muscle.

- Both innervations are autonomic and involuntary.[1]

In contrast to the previous autonomic pathways, a third innervation is that of the somatic motor nerves, which originate in the sacrum. These nerves act primarily on the external urethral sphincter, which is composed of striated muscle, and under voluntary control. When the somatic nerves stimulate the sphincter, it contracts and prevents urine from flowing.[1]

The PMC, also known as Barrington's nucleus, is located in the brainstem and works with other regions of the brain to coordinate micturition. The primary role of the PMC when it is activated is to stimulate urination. It achieves this through activation of parasympathetic neurons, triggering the detrusor muscle to contract and indirectly inhibits the somatic nerves that maintain the external sphincter closed in contraction.[3]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The Pontine micturition center(PMC) is located in the medial dorsal pons, close to, or includes the lateral dorsal tegmental nucleus and locus coeruleus.[4] Upon stimulation, PMC exerts dual effects of producing detrusor muscle contraction and urethral sphincter relaxation with consequent micturition. External urethral sphincter relaxation is mediated indirectly by suppressing Onuf's nucleus located in the sacral spinal cord. A PET(positron emission tomography) scan is the imaging modality that detects how tissues and organs are functioning by measuring blood flow, the extent of oxygen and sugar use. Increased blood flow has been demonstrated by PET scan in right dorsomedial pons during voiding. In contrast, PET scan during withholding of urine showed higher blood flow in the right ventral pons.[5][6] There are also suggestions that specific nuclei that control micturition predominantly exist in the right pons.[4] The pontine micturition center (PMC) coordinates the mechanical process of micturition, thus the sphincter and detrusor muscle activities of the urinary bladder. Afferents from the bladder relay on the PMC before to higher brain centers. And the higher brain centers of micturition communicate with PMC through the periaqueductal gray matter to either provoke or suppress the voiding reflex. When the urinary bladder becomes distended, the stretch receptors of the bladder wall transmits an afferent signal to the pons, which subsequently notifies the brain. This afferent signal results in a perception of bladder fullness or desire to urinate. The higher brain determines the appropriateness of initiating voiding reflex. Under typical situations, the higher brain suppresses PMC by transmitting inhibitory signals via the periaqueductal gray matter. Upon the PMC inhibition, the urge to urinate disappears, which allows delaying voiding until finding a socially acceptable place and time. In an appropriate time and place, the brain withdraws the suppression of the PMC, which allows initiating a micturition reflex. Regardless, the individual may consciously contract the pelvic floor muscles to keep the external urethral sphincter closed or suppress the voiding urgency by distracting techniques.

Periaqueductal gray(PAG) of the mesencephalon has a potential role in integrated movement patterns of both the somatic as well as the autonomic nervous system. PAG exerts its impact on micturition by its neural projections to the PMC. In fact, no direct connections exist between PAG and the sacral cord motoneurons. The central PAG receives afferents from the sacral cord, which in turn sends projections to the PMC. The PAG does not play an essential role in micturition reflex rather transmits afferent signals of the full bladder to higher brain centers. PAG serves only as a relay station during transmission of afferents from the bladder to the PMC. However, PMC is responsible for switching from urine storage to the voiding phase of the bladder.

A variety of neurotransmitters operate in the central control of the micturition. These neurotransmitters can categorize as excitatory such as glutamic acid, tachykinins, PACAP (pituitary-adenylate-cyclase-activating polypeptide), NO and ATP or inhibitory such as GABA glycine, enkephalins. Glutamate binds with NMDA and non-NMDA receptors and is the essential neurotransmitters in reflex pathways controlling the bladder and the urethral sphincter. Inhibitory neurotransmitters exert a tonic inhibition in the PMC and as well as in the spinal cord.

Embryology

During the third week of development, the notochord forms in the mesoderm, which in turn stimulates the differentiation of its overlying ectoderm to neuroectoderm. Later neuroectoderm thickens to form the neural plate. Neural folds form bilateral edges of the neural plate and then approach and fuse in the midline to form the neural tube. The cephalic end of the neural tube gives rise to three primary brain vesicles, prosencephalon, mesencephalon, and rhombencephalon. The rhombencephalon gives rise to the adult hindbrain by further division into secondary brain vesicles, metencephalon, and myelencephalon. Pons and cerebellum derive from the metencephalon, whereas medulla derives from the myelencephalon. Thus pontine micturition center is a part of the metencephalon of hindbrain vesicle.[7] However, reflex voiding is eventually modulated by the influence of higher brain centers until the nervous system has matured postnatally. During the prenatal period, before full maturation of the nervous system, bladder evacuation occurs by non-neural mechanisms and at later stages of development, by primitive reflex pathways at the spinal cord level. Extensive synaptic remodeling in the parasympathetic nucleus of the sacral cord and within the higher brain is an essential factor in the postnatal maturation of micturition reflexes.[1]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The pons is perfused by three sets of arteries, anteromedial, lateral, and dorsal. The anteromedial branches arise from the terminal portion of vertebral arteries and basilar artery. In contrast, the lateral branches derive from the anterior inferior cerebellar artery, superior cerebellar artery, and long pontine arteries. Finally, the dorsal group of arteries arise from the terminal superior cerebellar artery and nourish the locus coeruleus, the mesencephalic nucleus of the trigeminal nerve(CN V), and superior cerebellar peduncle. Blood supply to the pontine micturition center mostly derived from the perforating branches dorsal arteries, also, may receive the collateral circulation from the perforating branches of the anteromedial and lateral group of arteries.[8]

Surgical Considerations

Neurosurgical access to posterior pontine lesions bears higher chances of injury to PMC and accessed through the rhomboid fossa. Telovelar route or cerebellomedullary fissure approach is used to access the superior and posterior pontine lesions. The suprafacial triangle is an opening to the brainstem, which is located above the facial nerve, and bounded medially by medial longitudinal fasciculus(MLF) or the median sulcus, laterally by superior cerebellar peduncles and inferiorly by the facial nerve or facial colliculus. Although it is considered as a safe entry triangle, bipolar stimulation on the surface is recommended to localize the facial nerve course, which might have been distorted by the lesson. To preserve the MLF, entry to this zone should always be 2 mm from the midline.[8]

Clinical Significance

A dysfunctional voiding may result from any lesson affecting the micturition reflex arc(afferent and efferent nerves) or part of the CNS, including the higher brain centers, pons, anywhere within and above the sacral cord. CNS lesions above and below the pons interfere with the higher conscious control of urination regardless of the function of PMC, where PMC dysfunction or dissociation of PMC from the spinal micturition center results in loss of coordination between detrusor and urethral sphincter.

Supra-pontine circuitry can become disrupted by an anterior cerebral lesion or dopaminergic neurons degeneration in Parkinson disease. These supra-pontine lessons result in inhibitory control over the PMC, in turn, decreased bladder capacity and detrusor muscle overactivity. Preclinical studies have demonstrated that supra-pontine lesions lead to the upregulation of D2-dopaminergic and NMDA-glutamatergic excitatory and concurrent M1-muscarinic inhibitory mechanisms within the brain. Experimental animal models of cerebral infarction have shown increased expression of the immediate early genes (such as c-fos, Zif268) and Cox2 in the PMC and blockade these effects by NMDA-glutamatergic antagonist. The detrusor overactivity was reversed by blocking the c-fos, and Zif268 upregulation in the pons, detrusor overactivity in supra-pontine lesions is mediated in part by altered synaptic transmission in the PMC.[9][10] Any interruption between the PMC and lumbosacral spinal cord results in complete loss of voiding function, in turn, manifests urinary retention. Any interruption between the PMC and lumbosacral spinal cord results in total loss of voiding function, in turn, reveals urinary retention. In most of the instances, bladder reflexes slowly recover following spinal cord lesions. However, detrusor-sphincter dyssynergia frequently occurs due to compromised coordination between the bladder and sphincter activity. It is characterized by simultaneous bladder and external urethral sphincter contractions resulting in incomplete evacuation and urinary retention.

Urinary bladder dysfunction secondary to brainstem lesions is not a common encounter in clinical practice due to the rarity of brainstem lesions. In cases with brainstem stroke, tumors, or other mass lesions, the clinical manifestations are almost always dominated by other tract and cranial nerve findings. However, when present, internuclear ophthalmoplegia (INO) is a frequent accompanying deficit due to the proximity of the medial longitudinal fasciculus to the PMC. Posterior fossa tumor and pontine lesions affecting the dorsal aspect are the common scenarios to encounter voiding difficulty due to possible PMC involvement.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Fowler CJ, Griffiths D, de Groat WC. The neural control of micturition. Nature reviews. Neuroscience. 2008 Jun:9(6):453-66. doi: 10.1038/nrn2401. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18490916]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencede Groat WC, Griffiths D, Yoshimura N. Neural control of the lower urinary tract. Comprehensive Physiology. 2015 Jan:5(1):327-96. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c130056. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25589273]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSasaki M. Role of Barrington's nucleus in micturition. The Journal of comparative neurology. 2005 Dec 5:493(1):21-6 [PubMed PMID: 16255005]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceShukla R, Giri P, Bhandari A, Shankhwar SN. Pontine stroke and bladder dysfunction. BMJ case reports. 2014 May 29:2014():. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-200787. Epub 2014 May 29 [PubMed PMID: 24876208]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBlok BF, Willemsen AT, Holstege G. A PET study on brain control of micturition in humans. Brain : a journal of neurology. 1997 Jan:120 ( Pt 1)():111-21 [PubMed PMID: 9055802]

Stone E, Coote JH, Allard J, Lovick TA. GABAergic control of micturition within the periaqueductal grey matter of the male rat. The Journal of physiology. 2011 Apr 15:589(Pt 8):2065-78. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.202614. Epub 2011 Feb 21 [PubMed PMID: 21486804]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceElshazzly M, Lopez MJ, Reddy V, Caban O. Embryology, Central Nervous System. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30252280]

Cavalheiro S, Yagmurlu K, da Costa MD, Nicácio JM, Rodrigues TP, Chaddad-Neto F, Rhoton AL. Surgical approaches for brainstem tumors in pediatric patients. Child's nervous system : ChNS : official journal of the International Society for Pediatric Neurosurgery. 2015 Oct:31(10):1815-40. doi: 10.1007/s00381-015-2799-y. Epub 2015 Sep 9 [PubMed PMID: 26351233]

Yokoyama O, Yotsuyanagi S, Akino H, Moriyama H, Matsuta Y, Namiki M. RNA synthesis in pons necessary for maintenance of bladder overactivity after cerebral infarction in rat. The Journal of urology. 2003 May:169(5):1878-84 [PubMed PMID: 12686866]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGriffiths D, Tadic SD. Bladder control, urgency, and urge incontinence: evidence from functional brain imaging. Neurourology and urodynamics. 2008:27(6):466-74 [PubMed PMID: 18092336]