Introduction

Drug-induced pigmentation is a form of abnormal skin pigmentation that is caused by drugs through several different mechanisms. Several drugs have associations with pigmentation, including cytotoxic agents, analgesics, anticoagulants, antimicrobials, antiretrovirals, metals, and antiarrhythmic, etc. Various causes can contribute to the pigmentation that may involve an accumulation of melanin synthesis or even the synthesis of particular substances. Histological findings are relatively diverse but can include substances that are primarily within the dermal macrophages. Diagnosing a patient with drug-induced pigmentation can be difficult, as it is essential to rule out other conditions that may be leading to the skin findings.

Additionally, it is especially difficult to make the diagnosis in patients on multiple drugs. The recommendation is to perform a complete medical history, along with a thorough skin examination on the patient. The hope is that there will be more research on the specific effects of drug-induced pigmentation and potential treatment options.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Drug-induced pigmentation is the diagnosis when the pigmentation is temporally associated with drug use, and other potential causes have been ruled out. Several drugs can cause pigmentation from antimalarials to antiretrovirals. Therefore, clinicians should be vigilant in examining a patient’s full medical history to determine the specific drug that appears to be causing the patient’s symptoms.[1]

Epidemiology

The incidence of drug-induced pigmentation is difficult to ascertain because of a lack of reported cases and a dearth of information from patients regarding their treatment. However, estimates are that about 20% of cases of pigmentation are thought to be drug-induced. No significant differences between gender, age, and racial groups have been noted, although individuals with darker skin may display more severe hyperpigmentation.[2] More prospective studies investigating this issue are needed.[1][3]

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of drug-induced pigmentation is thought to involve several different mechanisms. It could be due to the accumulation of melanin (e.g., antimalarials), either by a direct trigger of the medication or nonspecific inflammation caused by the drug. This form of pigmentation is worsened by sun exposure, explaining patients’ worsened pigmentation in sunny areas. Additionally, the drug itself can accumulate and cause pigmentation. The drug can remain within dermal macrophages and even undergo chemical changes to newer types of particles, as exhibited by gold complexes. Finally, the last two mechanisms for drugs that can cause pigmentation involves the synthesis of new pigment (lipofuscin) or accumulation of iron (minocycline).[4] The latter is thought to involve damaged blood vessels and lysis of red blood cells.[3]

History and Physical

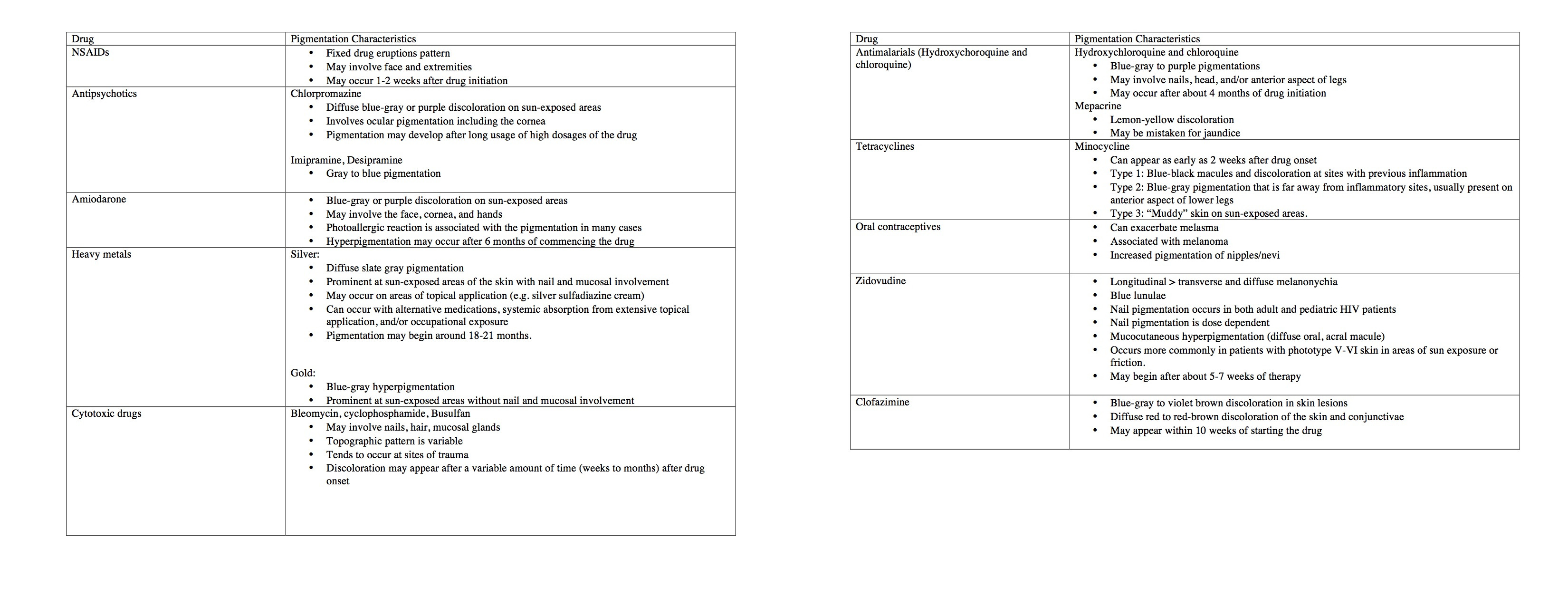

In regards to clinical findings, drug-induced pigmentation varies from other causes of pigmentation. The most crucial distinction is that when the treatment with the drug stops, the pigmentation also begins to fade. For example, with the discontinuation of paclitaxel, the pigmentation also resolves shortly thereafter.[5] The discoloration associated with drug-induced pigmentation also tends to have a slower occurrence, with gradually worsening over months to a year. Moreover, particular drugs may have specific patterns of pigmentation. For example, NSAIDS typically involve fixed eruptions, whereas psychotropics are known for presenting with a blue-gray appearance and are related to sun exposure. Certain drugs are also associated with nail pigmentation. For example, antimalarials are more likely to cause nail beds that have transversal bands, whereas cytotoxic drugs such as cisplatin are more likely to present with longitudinal pigmented bands.[3] See the table for an overview of the characteristic pigmentation findings associated with particular drugs.

Evaluation

When evaluating whether a patient has pigmentation related to medication use, it is crucial to take into consideration several points. First, it is vital to take a thorough medical history of the patient, which involves noting all the medications the patient is taking and carefully evaluating any that have pigmentation-related side effects. Common drugs that are known to cause pigmentation include NSAIDS, antimalarials, amiodarone, anticoagulants, antimicrobials, antiretrovirals, and tetracyclines. Additionally, a provider should note when the pigmentation starts and if there are any changes, such as increased or decreased intensity, after altering the usage of the drug. For example, amiodarone-induced pigmentation exhibits a dose-dependent relationship in regards to its appearance.[6]

Treatment / Management

Initially, if there is another drug that can substitute as therapy for the patient’s condition, then that should be a consideration. If that is not possible, an effective approach involves reducing the dosage of a drug. Some drugs such as amiodarone have a dose-dependent correlation with the amount of discoloration experienced.[3] In these cases, decreasing the intake of a drug can dramatically reduce the dyschromia present. Additionally, specific drug-induced pigmentation is avoidable by limiting sun exposure. These drugs include antimalarials, psychotropic, amiodarone, and tetracyclines.[3] In these cases, patients should receive counsel on proper outside wear, such as sunglasses and protective, covered clothing. If the suggestions mentioned above failed to work, there are also some topical and laser treatments available. However, the efficacy of these treatment methods remains elusive.

Differential Diagnosis

Several pigmentation-related skin conditions should merit consideration before a diagnosis of drug-induced pigmentation is made. Melasma can present as a light, dark brownish discoloration. Addison disease usually involves pigmentation of the oral mucosa. Blue nails are one of the characteristic findings of Wilson disease, which also includes visceral involvement of other organs such as the liver. Vitamin deficiencies, such as niacin, can present with pellagra and the classic triad of dementia, diarrhea, and dermatitis.[7] Finally, Kaposi sarcoma should be on the differential for HIV-infected individuals.

Prognosis

The prognosis of the pigmentation is generally good, but extra-dermal manifestations of the pigmentation may exacerbate it. For example, hydroxychloroquine may cause pigmentation of the oral mucosa, and minocycline can cause pigmentation of heart valves.[8][9] Otherwise, drug-induced pigmentation does not correlate with increased mortality. There may be psychological or social impacts depending upon the individual patient.

Complications

The complications and associated symptoms of the pigmentation depend on the specific drug. NSAIDs are known to cause fixed drug eruptions, most probably through a hapten-type interaction. Antimalarials, amiodarone, and antipsychotics involve blue to gray discoloration in various areas from the face to the lower extremities. Anticonvulsants can cause brown-gray discoloration that resembles melasma. The pigmentation can also deposit in other areas such as the nails (antimalarials and minocycline). Antipsychotics, antimalarials, and amiodarone can even lead to corneal pigmentation.[3]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patient education is vital in all stages of managing drug-related pigmentation from diagnosis to treatment. Obtaining a thorough medical history is crucial for making a diagnosis of drug-induced pigmentation. Therefore, it is necessary that patients provide a full, accurate history regarding their past and current medication use. Additionally, when removing or adjusting the medication used for treating drug-induced pigmentation, it is essential that the patient correctly understand the new regimen of the medication to avoid further exacerbation of the pigmentation caused by the previous drug usage. For drugs that are associated with sun exposure, patients should understand the importance of sun protection.[10]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

A coordinated effort is especially needed when it comes to managing drug-induced pigmentation. Dermatologists need to work with patient’s other specialists come up with the best medication or dosage to avoid the pigmentation-related symptoms as much as possible. Moreover, future medical providers should be aware of the patient’s history of drug-relate pigmentation so that they can be mindful of the issue when prescribing new medications.

Addressing pigmentation secondary to drug therapy requires an interprofessional team approach, including physicians, specialists, specialty-trained nurses, and pharmacists, all collaborating across disciplines to achieve optimal patient results. [Level V]

Media

References

Nahhas AF, Braunberger TL, Hamzavi IH. An Update on Drug-Induced Pigmentation. American journal of clinical dermatology. 2019 Feb:20(1):75-96. doi: 10.1007/s40257-018-0393-2. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30374894]

Halder RM, Nandedkar MA, Neal KW. Pigmentary disorders in ethnic skin. Dermatologic clinics. 2003 Oct:21(4):617-28, vii [PubMed PMID: 14717403]

Dereure O. Drug-induced skin pigmentation. Epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment. American journal of clinical dermatology. 2001:2(4):253-62 [PubMed PMID: 11705252]

Bell AT, Roman JW, Gratrix ML, Brzezniak CE. Minocycline-Induced Hyperpigmentation in a Patient Treated with Erlotinib for Non-Small Cell Lung Adenocarcinoma. Case reports in oncology. 2017 Jan-Apr:10(1):156-160. doi: 10.1159/000452146. Epub 2017 Feb 15 [PubMed PMID: 28413391]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCohen PR. Paclitaxel-associated reticulate hyperpigmentation: Report and review of chemotherapy-induced reticulate hyperpigmentation. World journal of clinical cases. 2016 Dec 16:4(12):390-400. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v4.i12.390. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28035312]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKounis NG, Frangides C, Papadaki PJ, Zavras GM, Goudevenos J. Dose-dependent appearance and disappearance of amiodarone-induced skin pigmentation. Clinical cardiology. 1996 Jul:19(7):592-4 [PubMed PMID: 8818442]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYamaguchi Y, Hearing VJ. Melanocytes and their diseases. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine. 2014 May 1:4(5):. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a017046. Epub 2014 May 1 [PubMed PMID: 24789876]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSant'Ambrogio S, Connelly J, DiMaio D. Minocycline pigmentation of heart valves. Cardiovascular pathology : the official journal of the Society for Cardiovascular Pathology. 1999 Nov-Dec:8(6):329-32 [PubMed PMID: 10615019]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKleinegger CL, Hammond HL, Finkelstein MW. Oral mucosal hyperpigmentation secondary to antimalarial drug therapy. Oral surgery, oral medicine, oral pathology, oral radiology, and endodontics. 2000 Aug:90(2):189-94 [PubMed PMID: 10936838]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWeiss SR, Lim HW, Curtis G. Slate-gray pigmentation of sun-exposed skin induced by amiodarone. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1984 Nov:11(5 Pt 1):898-900 [PubMed PMID: 6512044]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence