Introduction

Pectus carinatum or “keel chest,” like its sister condition pectus excavatum, is a congenital deformation of the anterior chest wall. The condition presents with an outward protrusion of the sternum or rib cage.[1] When the sternal manubrium is prominent, the deformity is often called “pigeon breast,” while the more common chondrogladiolar prominence, in which the body of the sternum protrudes, is referred to as “chicken breast.”[2] The deformity can be symmetric or unilateral, with a rightward tilt of the sternum the more common unilateral condition.[3] Unlike pectus excavatum, pectus carinatum is typically not identified shortly after birth but during the teen years when growth is accelerated. It can be perceived as early as age 10, with a peak at 16 years and 18 years in females and males respectively.[4] The condition is often asymptomatic, with patients seeking treatment for cosmetic reasons. When symptoms present, they typically present only as tenderness at the location of the protrusion.[2] Other symptoms related to the decreased compliance of the chest seen in more pronounced cases include dyspnea, tachypnea with exertion, and reduced endurance.[5]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The precise etiology of pectus carinatum is unknown, although most believe both pectus carinatum and pectus excavatum to be due to defective elongated growth of the costal cartilage.[3] Additional studies have shown a relationship between sternal growth and pectus carinatum, with a greater association seen in the superior chondromanubrial deformities.[6] A genetic component is suggested by the significant portion of patients with a family history of a chest wall defect or deformity, with estimates as high as 25 to 33%.[2][3]

Epidemiology

Pectus carinatum is estimated to occur in up to 0.06% of all live births, with an incidence of approximately 1 per 1000, seen in teenagers. With more detailed radiographic evidence available with computed tomography (CT), there are suggestions that milder forms of pectus carinatum may occur in up to 5% of the population.[3] Males are more frequently affected, at a ratio of nearly four to one.[2]

History and Physical

Patients with pectus carinatum present with protrusion of the sternum and ribs, often asymptomatic but occasionally with tenderness at the protrusion site, reduced pulmonary endurance, or tachypnea with exertion. Respiratory symptoms such as dyspnea and reduced endurance are more common in the chondromanubrial variety, as the flexibility of the chest wall is decreased compared to the chondrogladiolar deformity.[7] The protrusion can be bilateral or unilateral. There is a family history of chest wall deformity in up to one-third of patients.[3] The condition correlates with scoliosis, Marfan syndrome, mitral valve prolapse, homocystinuria, Morquio syndrome, Noonan syndrome, and osteogenesis imperfecta, though frequently occurs in isolation.[2][3] Some studies have shown an association with asthma or chronic bronchitis in up to 16.4% of patients.[4]

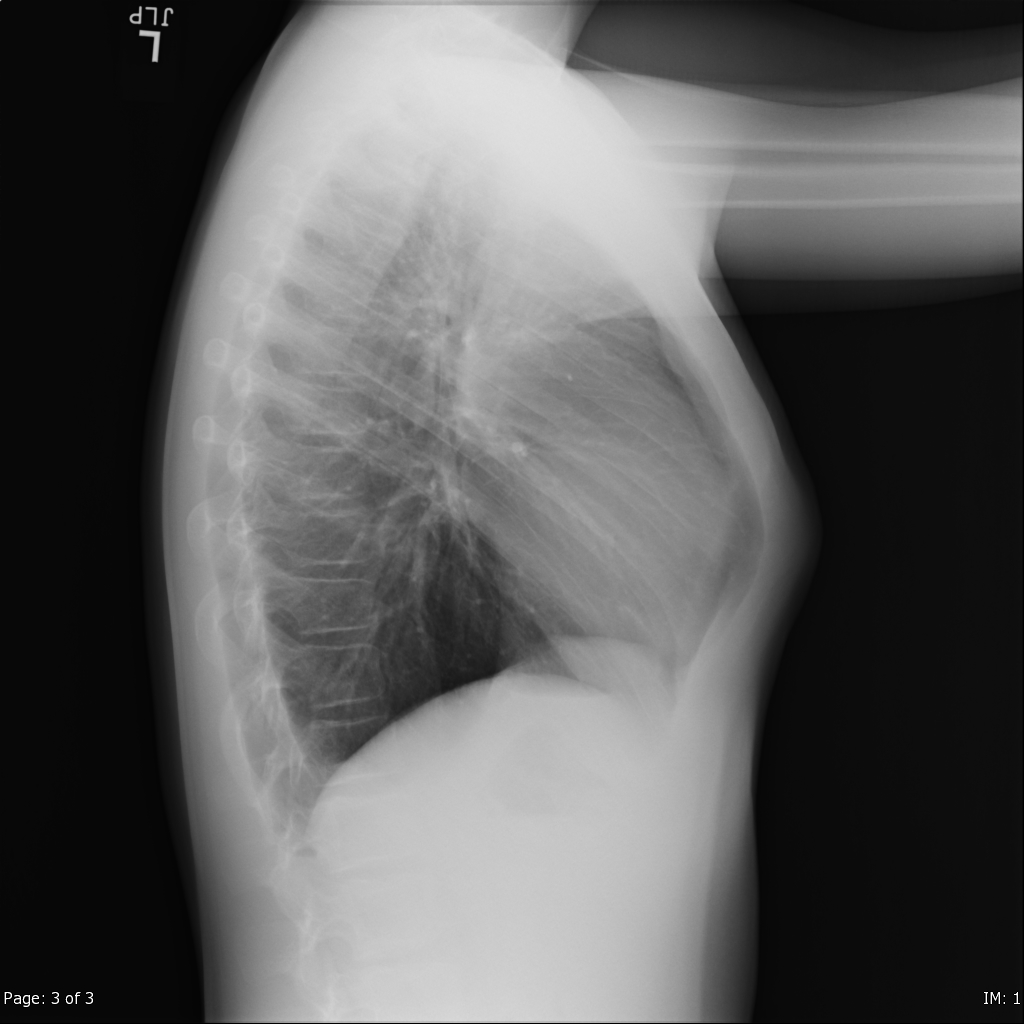

Evaluation

Diagnosis of pectus carinatum is made clinically by visual inspection, with further details offered by lateral chest radiograph or computed tomography (CT). Evaluation of the severity of the deformity is performed radiographically utilizing the Haller index, the ratio of the transverse diameter of the chest wall to the greatest anteroposterior diameter. Studies suggest that chest radiographs are as effective as CT in determining the Haller index, with the additional benefit of decreased radiation exposure to the patient.[8][9] In addition to grading severity, the Haller index also measures treatment progress.

Treatment / Management

Treatment of pectus carinatum typically falls into one of three categories: non-surgical bracing, surgical correction, or cosmetic concealment. Orthotic braces are the first option for treatment as acceptable results are often achievable, and the use of the external brace does not preclude surgical intervention if it is unsuccessful.[10] The braces are worn either under or over the patient’s clothing for between 14 and 24 hours per day, depending on the manufacturer and the severity of the chest wall protrusion. A non-surgical correction is most effective when applied before the patient’s growth spurt and less effective after age 19 due to changes in the flexibility of the chest wall.[11] However, due to the lengthy treatment period (often months to years) and slow progression of the correction, many patients do not view this as an acceptable option.(B2)

Surgical repair has been classically performed using the technique developed by Ravitch in 1949.[12] This invasive procedure involves an incision of the anterior chest wall and elevation of the pectoralis major muscle followed by resection of the deformed costal cartilage. Transverse sternotomy follows with fixation of the corrected shape of the chest wall.[13] This method is now infrequently utilized as less invasive techniques have been developed. A minimally invasive method developed by Abramson utilizes a modified Nuss bar used in the correction of pectus excavatum and has been in extensive use since 2006.[14] A metal bar is inserted into the presternal space through an incision on the lateral chest wall and secured to the bilateral ribs with metal plates. The bar is left in place for approximately 2 years and then removed. Though now the favored surgical option, this modified Nuss procedure is used primarily with the chondrogladiolar type of pectus carinatum due to the decreased flexibility of the chest wall in the chondromanubrial variation.[7](B3)

Some patients not seeking medical treatment for correction have turned to bodybuilding to sculpt the musculature around the chest wall deformity in a way that minimizes the appearance of the protrusion. While this does not correct the abnormality, it can improve self-esteem and confidence. For female patients, breast augmentation has also been used to alter the physical appearance of the chest to make the pectus carinatum less apparent.

Differential Diagnosis

The diagnosis of pectus carinatum is made by visual inspection with or without radiographic support. Most incidences occur in isolation, though there is a strong association with several conditions for which the patient may require evaluation. Marfan syndrome, a connective tissue disorder affecting up to 0.3% of the general population,[15] frequently presents with a pectus deformity. Two-thirds of patients with Marfan syndrome have a pectus deformity, with 12% of those being pectus carinatum. It is appropriate to refer patients with a pectus deformity for evaluation as more than 5% of those presenting with pectus carinatum, or pectus excavatum will also have Marfan syndrome.[15]

Another syndrome that has a strong association with pectus carinatum is Morquio syndrome or mucopolysaccharidosis type IVA.[16] This rare genetic disease of dysfunctional glycosaminoglycan catabolism occurs in approximately 1 in 200000 births and presents with scoliosis, short stature, hypermobile joints, a bell-shaped chest, and cardiac abnormalities. The severe form of this disease becomes apparent at an early age with knock-knees and breastbone prominence, whereas the more slowly progressing variety may not become apparent until adolescence.

Prognosis

The prognosis for patients diagnosed with pectus carinatum is excellent. Even without treatment, patients may have no symptoms and no long term adverse health effects. Treatment is typically for cosmetic reasons, and both external bracing and minimally invasive surgical techniques have demonstrated the ability to achieve improvement in the appearance of the chest wall.

Complications

An often overlooked aspect of pectus carinatum is the psychological impact the deformity has on the patient. Presentation of the condition occurs during the teenage years when body image formation is occurring. Coping strategies may develop, such as wearing clothes that minimize the appearance of pectus or withdrawing from group activities and team sports to avoid the unwanted attention of their peers. Those that pursue cosmesis with body-building should be made aware that the American Academy of Pediatrics does not support that level of strenuous activity in children whose skeletons are still maturing.[17]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Written materials regarding pectus carinatum should be provided to the patient by their healthcare provider and should be encouraged to ask about any questions and concerns about their condition and what the available treatment options are. When appropriate, patients should be referred to a specialist who will be better able to provide support, treatment, or further evaluation.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Pectus carinatum is a diagnosis that can be made on visual inspection by health care professionals at every level. Pediatricians, primary care providers, and nurse practitioners are often the first to evaluate these patients and determine if further assessment or treatment is needed. Coordination with team members in radiology, surgery, nursing, and psychiatry can provide patients a means to treat, monitor, and cope with the condition.

Management of pectus carinatum is best with an interprofessional team comprised of physicians, surgeons, specialty-trained nursing, and therapists working and communicating collaboratively to achieve the best patient outcomes. {level V]

Media

References

Park CH, Kim TH, Haam SJ, Lee S. Does overgrowth of costal cartilage cause pectus carinatum? A three-dimensional computed tomography evaluation of rib length and costal cartilage length in patients with asymmetric pectus carinatum. Interactive cardiovascular and thoracic surgery. 2013 Nov:17(5):757-63. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivt321. Epub 2013 Jul 17 [PubMed PMID: 23868604]

Goretsky MJ, Kelly RE Jr, Croitoru D, Nuss D. Chest wall anomalies: pectus excavatum and pectus carinatum. Adolescent medicine clinics. 2004 Oct:15(3):455-71 [PubMed PMID: 15625987]

Robicsek F, Watts LT. Pectus carinatum. Thoracic surgery clinics. 2010 Nov:20(4):563-74. doi: 10.1016/j.thorsurg.2010.07.007. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20974441]

Coelho Mde S, Guimarães Pde S. Pectus carinatum. Jornal brasileiro de pneumologia : publicacao oficial da Sociedade Brasileira de Pneumologia e Tisilogia. 2007 Jul-Aug:33(4):463-74 [PubMed PMID: 17982540]

Fonkalsrud EW. Surgical correction of pectus carinatum: lessons learned from 260 patients. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2008 Jul:43(7):1235-43. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2008.02.007. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18639675]

Haje SA, Harcke HT, Bowen JR. Growth disturbance of the sternum and pectus deformities: imaging studies and clinical correlation. Pediatric radiology. 1999 May:29(5):334-41 [PubMed PMID: 10382210]

Katrancioglu O, Akkas Y, Karadayi S, Sahin E, Kaptanoğlu M. Is the Abramson technique effective in pectus carinatum repair? Asian journal of surgery. 2018 Jan:41(1):73-76. doi: 10.1016/j.asjsur.2016.09.008. Epub 2016 Nov 4 [PubMed PMID: 27825548]

Poston PM, McHugh MA, Rossi NO, Patel SS, Rajput M, Turek JW. The case for using the correction index obtained from chest radiography for evaluation of pectus excavatum. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2015 Nov:50(11):1940-4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2015.06.017. Epub 2015 Jun 30 [PubMed PMID: 26235532]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKhanna G, Jaju A, Don S, Keys T, Hildebolt CF. Comparison of Haller index values calculated with chest radiographs versus CT for pectus excavatum evaluation. Pediatric radiology. 2010 Nov:40(11):1763-7. doi: 10.1007/s00247-010-1681-z. Epub 2010 May 15 [PubMed PMID: 20473605]

Cohee AS, Lin JR, Frantz FW, Kelly RE Jr. Staged management of pectus carinatum. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2013 Feb:48(2):315-20. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2012.11.008. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23414858]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceJung J, Chung SH, Cho JK, Park SJ, Choi H, Lee S. Brace compression for treatment of pectus carinatum. The Korean journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2012 Dec:45(6):396-400. doi: 10.5090/kjtcs.2012.45.6.396. Epub 2012 Dec 7 [PubMed PMID: 23275922]

RAVITCH MM. Unusual sternal deformity with cardiac symptoms operative correction. The Journal of thoracic surgery. 1952 Feb:23(2):138-44 [PubMed PMID: 14909306]

Kálmán A. Initial results with minimally invasive repair of pectus carinatum. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2009 Aug:138(2):434-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.12.032. Epub 2009 Mar 9 [PubMed PMID: 19619792]

Abramson H. [A minimally invasive technique to repair pectus carinatum. Preliminary report]. Archivos de bronconeumologia. 2005 Jun:41(6):349-51 [PubMed PMID: 15989893]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBehr CA, Denning NL, Kallis MP, Maloney C, Soffer SZ, Romano-Adesman A, Hong AR. The incidence of Marfan syndrome and cardiac anomalies in patients presenting with pectus deformities. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2019 Sep:54(9):1926-1928. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2018.11.017. Epub 2018 Dec 27 [PubMed PMID: 30686517]

Tomatsu S, Mackenzie WG, Theroux MC, Mason RW, Thacker MM, Shaffer TH, Montaño AM, Rowan D, Sly W, Alméciga-Díaz CJ, Barrera LA, Chinen Y, Yasuda E, Ruhnke K, Suzuki Y, Orii T. Current and emerging treatments and surgical interventions for Morquio A syndrome: a review. Research and reports in endocrine disorders. 2012 Dec:2012(2):65-77 [PubMed PMID: 24839594]

American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Sports Medicine and Fitness, McCambridge TM, Stricker PR. Strength training by children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2008 Apr:121(4):835-40. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3790. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18381549]