Anatomy, Head and Neck, Nose Paranasal Sinuses

Anatomy, Head and Neck, Nose Paranasal Sinuses

Introduction

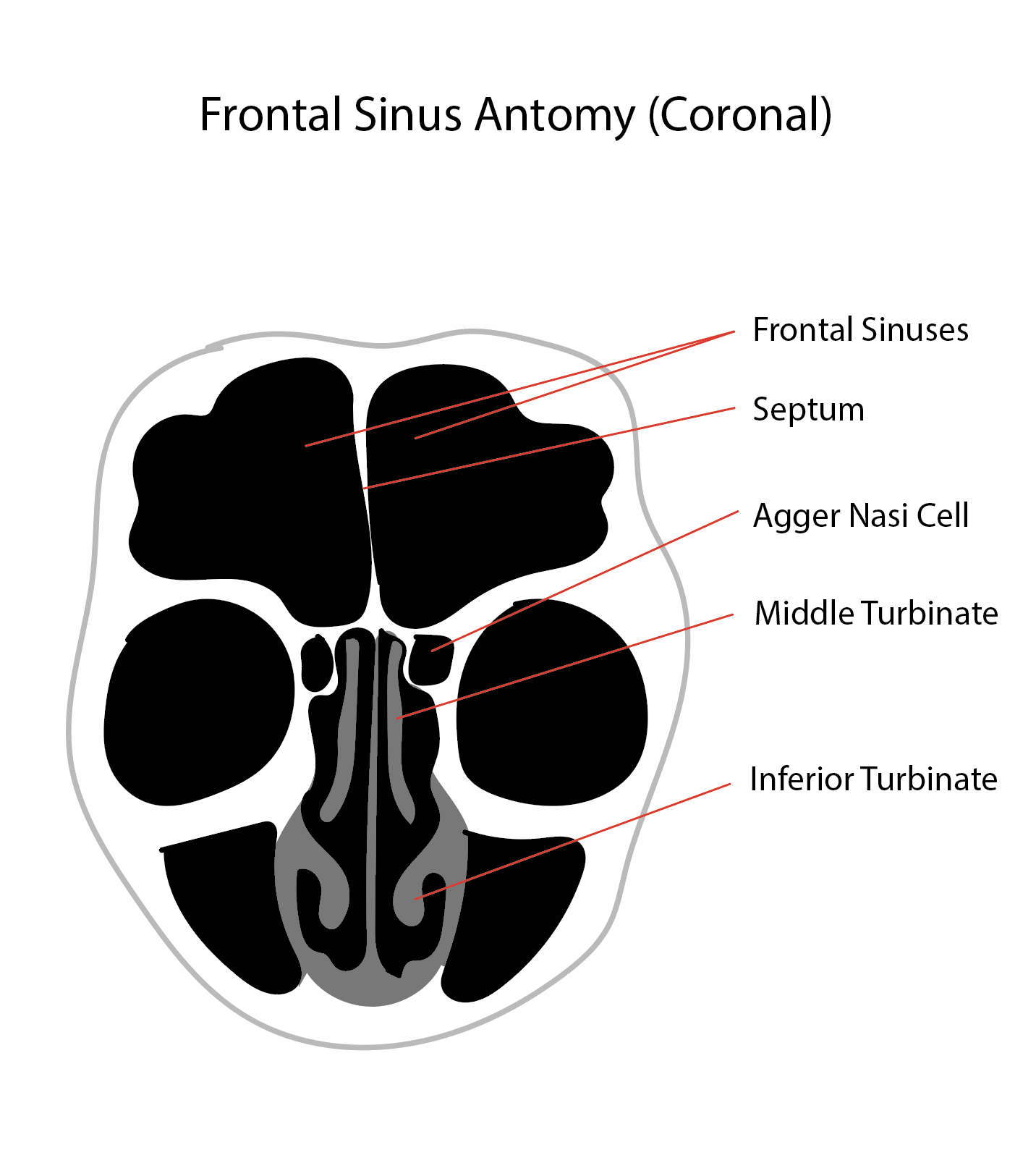

The nasal cavity is a roughly cylindrical, midline airway passage that extends from the nasal ala anteriorly to the choana posteriorly.[1] It is divided in the midline by the nasal septum. On each side, it is flanked by the maxillary sinuses and roofed by the frontal, ethmoid, and sphenoid sinuses in an anterior-to-posterior fashion.[1] While seemingly simple, sinonasal anatomy comprises intricate and subdivided air passages and drainage pathways that connect the sinuses. See Image. Diagram of the Frontal Sinus Anatomy, Coronal View.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

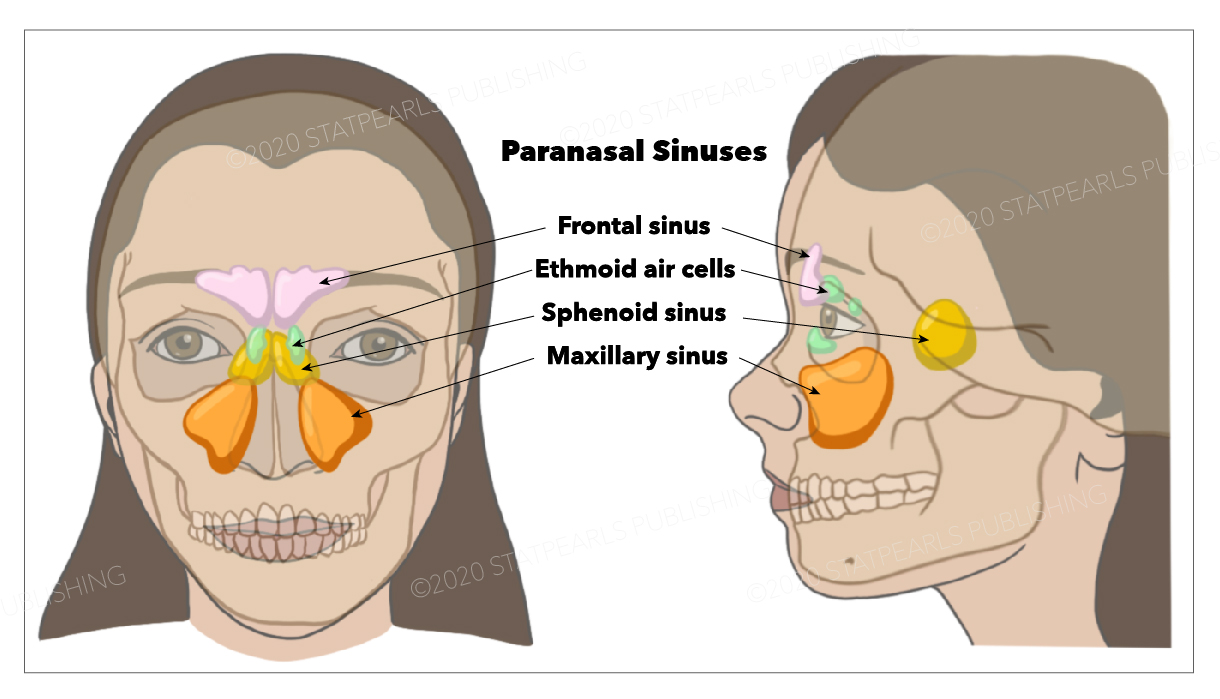

There are 4 paired sinuses in humans, all lined with pseudostratified columnar epithelium: the maxillary sinuses, the largest ones located under the eyes in the maxillary bones; the frontal sinuses, superior to the eyes within the frontal bone; the ethmoid sinuses, formed from several air cells within the ethmoid bone between the nose and eyes; and the sphenoid sinuses, located within the body of the sphenoid bone.[2] See Image. Paranasal Sinuses.

The function of the paranasal sinuses is debated. However, they are believed to be implicated in several roles: decreasing the relative weight of the skull, increasing the resonance of the voice, providing a buffer against facial trauma, insulating sensitive structures from rapid temperature fluctuations in the nose, and humidifying and heating inspired air. Furthermore, they also play a role in immunological defense. Learning the anatomical relationships of the sinuses to surrounding structures develops a strong understanding of paranasal sinus anatomy. The lateral nasal wall contains many structures and recesses that are relevant to paranasal sinus anatomy:

Turbinates

They are 3 to 4 bony shelves covered by erectile mucosa that increase the interior surface area.

Meatuses

The meatuses are 3 spaces located beneath each turbinate. The superior meatus drains for the sphenoid and posterior ethmoid sinuses. The middle meatus drains the frontal, anterior ethmoid, and maxillary sinuses. The inferior meatus contains the orifice of the nasolacrimal duct.

Uncinate Process

The uncinate process is a delicate, sickle-shaped, bony part of the ethmoid bone, covered by mucoperiosteum, medial to the ethmoid infundibulum, and lateral to the middle turbinate. Its anterior attachment corresponds to the lacrimal bone, and its inferior 1 corresponds to the ethmoidal process of the inferior turbinate and the perpendicular process of the palatine bone.[3] The superior attachment can be inconsistent.[3]

Ethmoid Infundibulum

The ethmoid infundibulum is a pyramidal space that facilitates the drainage of the maxillary, anterior ethmoid, and frontal sinuses.[4] The superior attachment of the uncinate process determines the spatial relationship of the frontal sinus drainage.

Semilunar Hiatus

The semilunar hiatus is the gap that empties the ethmoid infundibulum, which is located between the uncinate process and the ethmoid bulla.

Osteomeatal Complex (OMC)

The osteomeatal complex is a lateral nasal wall region drains the anterior ethmoid cells and the maxillary and frontal sinuses lateral to the middle turbinate. It is not a discrete anatomic structure but a collection of several components, including anterior ethmoid air cells, maxillary sinus ostium, ethmoid infundibulum, frontal recess, the middle meatus, the hiatus semilunaris, the bulla ethmoidalis, and the uncinate process.[4][3][4]

Nasal Fontanelles

The nasal fontanelles are described as an area of the lateral nasal wall without bone. The natural ostium of the maxillary sinus is located in the anterior fontanelle.

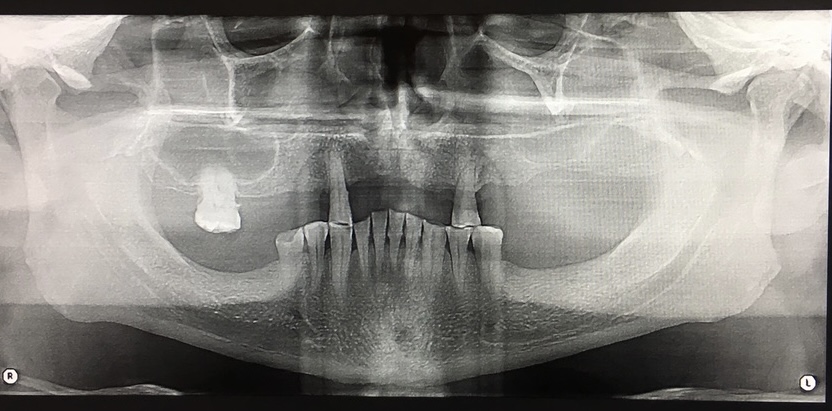

Maxillary Sinus

The maxillary sinus is a pneumatic cavity in the maxillary bone (see Image. Right and Left Maxillary Sinuses, Panoramic Radiograph).[5] It is pyramidal, with a base looking to the nasal cavity, anterior, posterior, and superior walls, and a lateral blunt apex extending into the maxillary bone's zygomatic process. The size of the maxillary sinus at the adult stage is approximately 15 mL,[6] making it the largest paranasal sinus. The anterior wall corresponds to the facial surface of the maxillary bone, with 3 identified landmarks – the canine fossa and the infraorbital foramen and groove. The infraorbital foramen is located 5 to 8 mm below the midpoint of the inferior margin of the orbit.[7] The posterior wall correlates to the maxillary tuberosity, which shapes the anterior surface of the pterygopalatine fossa.[8] The posterior wall is closely related to the contents of the pterygopalatine fossa, including the pterygopalatine ganglion and several branches of the maxillary artery, vein, and nerve.[9] Tumors and infections of the maxillary sinus and oral cavity can extend to the pterygopalatine fossa and affect these essential structures.

The orbit floor forms the superior wall, the sinus roof. The infraorbital artery (branch of the maxillary artery) and nerve (branch of the maxillary division of the trigeminal nerve) run through this wall and enter the infraorbital groove.[9] The medial wall separates the maxillary sinus from the nasal cavity. Still, they communicate throughout the ostium, located in the medial wall inferior or at the same level of the orbit floor.[9] The inferior wall, known as the sinus floor, is closely related to the posterior teeth apices, from which it is separated only by a layer of compact bone. The mean distance between the dental apices and the sinus floor is 1.97 mm,[10] and the apices of the molars are closer to the sinus floor than the premolars.[10] The first molars have been found to perforate the sinus floor in 2.2% of cases, and the second molars in 2% of cases. The buccodistal root of the second molar is the closest to the maxillary sinus floor.[2] The maxillary sinuses frequently present septa, thin plates of cortical bone arising from the sinus floor, better visualized on cone-beam CT scans. Primary septa occur during the development of the sinus [11], whereas secondary septa occur after tooth loss.[12] Apart from septa, tooth loss causes a local lowering of the sinus floor and alveolar bone resorption.[9] Mucus-producing ciliated pseudostratified columnar epithelium lines the maxillary sinus, which lacks periosteum. The cilia have the heavy task of draining the mucous into the ostium (located superiorly in the medial wall), and they are more numerous near the ostium.[2]

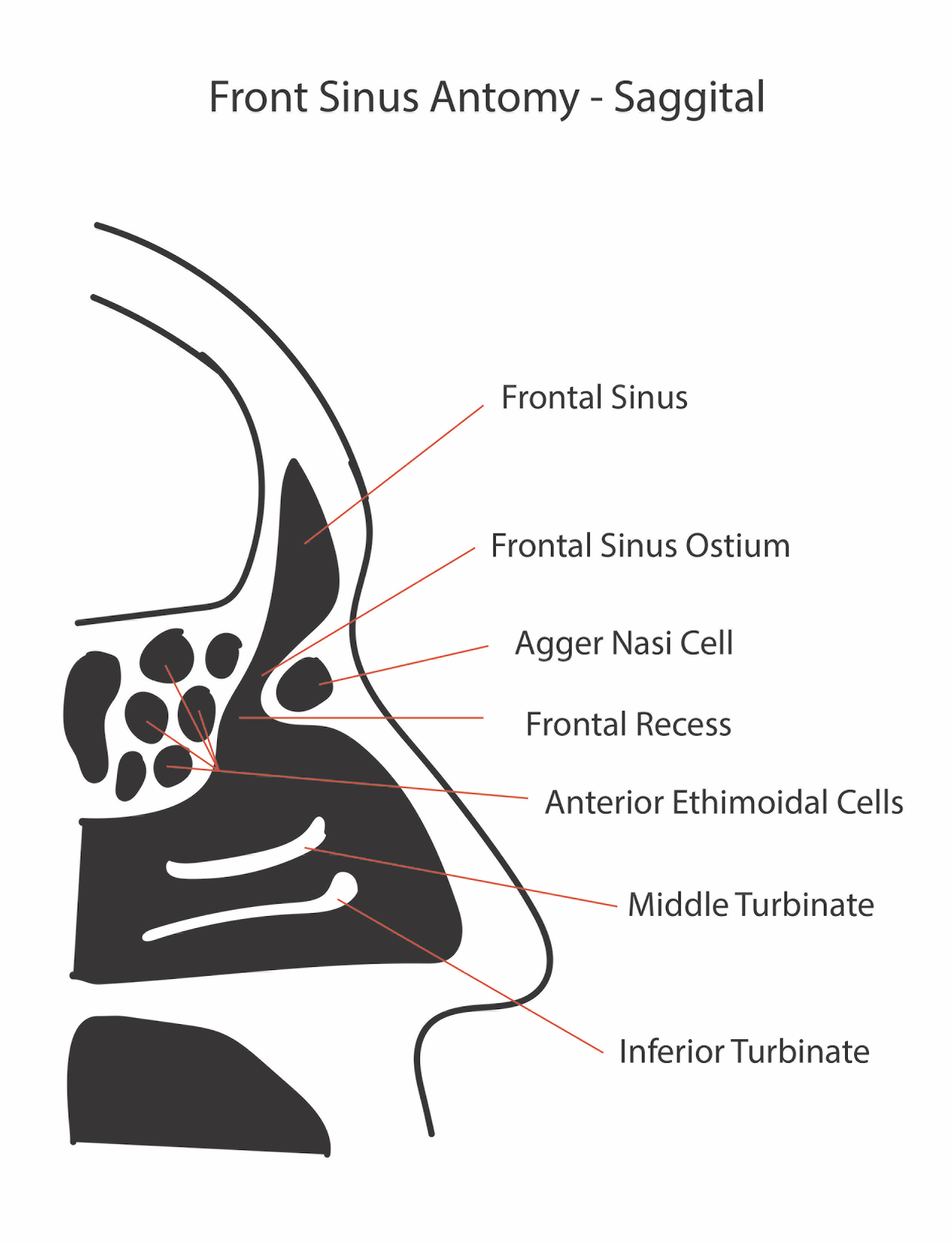

Frontal Sinus

The frontal sinus is a highly variable air-filled anatomical structure located superior to the orbit and within the frontal bone. Its shape and size depend on climate and ethnicity but is more or less pyramidal in adults, [13] and the typical volume is 4 to 7 mL. The frontal sinus is divided into 2 cavities by the frontal septum (see Image. Diagram of the Frontal Sinus Anatomy, Sagittal View). Several anatomical structures are important to frontal sinus anatomy, and they include:

Frontal Sinus Infundibulum and Ostium

The frontal infundibulum is a conically tapering constriction located in the frontal sinus floor,[14] superior to the agger nasi cells, and drains into the frontal recess. It is a transition zone between the frontal sinus and the frontal recess, and its narrowest area is known as the ostium.[15]

Frontal Recess

The frontal recess is the space posterior to the frontal beak into which the frontal sinus drains.[15] It is anteriorly bounded by the posterior wall of the agger nasi cell, laterally by the lamina papyracea, and medially by the middle turbinate.[15][4][15] Several cells cover this space and influence the direction of the drainage outflow.[15] The frontal recess is a common site of infection, and its surgical approach is known to be challenging.[4] The recess can open into the middle meatus in more than half of individuals or into the ethmoid infundibulum in the rest.[4]

Frontal Cells

In 2016, a group of experts developed The International Frontal Sinus Anatomy Classification to provide a better understanding to the surgeons of the variable and complicated frontal sinus recess and frontal sinus anatomy.[15] The resulting classification is described below:

Anterior Cells

The agger nasi, supra, and supra agger frontal cells form the anterior cells. They push the drainage in a medial, posterior, or posteromedial direction.

Agger Nasi Cell

The most anterior ethmoidal cell is known as the Agger nasi cell.[15] Almost all patients have this cell, which is an ethmoturbinal remnant; to accurately view the frontal recess, the agger nasi cells must be opened.[4] The agger nasi cell can be located 1) anterior to the middle turbinate origin or 2) directly superior to the most anterior middle turbinate insertion into the lateral nasal wall.

Supra Agger Cell

This anterior-lateral ethmoidal cell sits superior to the agger nasi cell but does not pneumatize into the frontal sinus.

Supra Agger Frontal Cell

This is an anterior lateral ethmoidal cell extending into the frontal sinus. The extension level of these cells into the frontal sinus depends on their size. If small, they usually only extend into the sinus floor. If large, they extend more into the sinus, elongating even into the sinus roof.

Posterior Cells

The posterior cells include the supra bulla cell, the supra bulla frontal cell, and the supraorbital ethmoid cell. They push the drainage in an anterior direction.

Supra Bulla Cell

It sits superior to the bulla ethmoidalis and does not enter the frontal sinus.

Supra Bulla Frontal Cell

This cell's origin is the suprabulla region, hence its name; it pneumatics into the frontal sinus posterior area. The posterior wall of this cell is the skull base.

Supraorbital Ethmoid Cell

This anterior ethmoid cell pneumatizes anterior, posterior, or around the anterior ethmoidal artery on the orbit's roof. If the frontal sinus is extensively pneumatized, the supraorbital ethmoid cell may be a part of the sinus' posterior wall, requiring bony septation to separate it from the sinus.

Medial Cells

The frontal septal cells are classified as medial cells. These are medially based cells of the inferior frontal sinus or the anterior ethmoid sinus; they are attached to the interfrontal sinus septum. They push the drainage in a lateral and often posterior direction.

Sphenoid Sinus

The sphenoid sinus is located centrally and posteriorly within the body of the sphenoid bone [16], and the sella turcica posteriorly and superiorly bounds it. The sphenoid sinus, present only in humans and primates,[16] can be identified in radiographs from the age of 2.[17] It keeps developing throughout life but matures in size at around 12 to 14 years of age.[16] The typical adult size is 0.5 to 8 mL. Several important structures are closely related to the sphenoid sinus, including the internal carotid artery and the optic nerve.[18] The carotid artery is located adjacent to the lateral wall of the sinus, and in 25% of patients, it is dehiscent in this area. The optic nerve leaves an anteroposterior indentation on the roof of the sphenoid, and the overlying bone can be dehiscent in around 4% of individuals.[18] The sphenoid sinus is also adjacent to the cavernous sinus and hypophysial gland.[16]The patterns of the sphenoidal sinus pneumatization were classified into conchal, pre-sellar, and sellar, depending on the extension of pneumatization concerning the sella turcica. But, Štokovic et al added a fourth type – post-sellar.[19] The sphenoid ostium drains into the sphenoethmoidal recess located within the superior meatus.

Ethmoid Sinuses

The ethmoid bone is formed by many cells with an intricated structure through which all the paranasal sinuses drain.[20] 3 to 4 ethmoid air cells at birth develop into 5 to 15 paired cells by adulthood with a total volume of 2 to 3 mL. They are located between the eyes, on either side of the septum. The anterior ethmoid cells drain into the ethmoid infundibulum in the middle meatus.[21] The posterior ethmoid cells drain into the sphenoethmoidal recess located in the superior meatus. The complex ethmoidal labyrinth can be reduced into a series of lamellae based on embryologic precursors. These lamellae are obliquely oriented and lie parallel to each other.

- The first lamella is the uncinate process.

- The second lamella corresponds to the ethmoid bulla.

- The third lamella is also known as the basal or ground lamella of the middle turbinate. It serves as the division of the anterior and posterior ethmoids.[22] The anterior part inserts vertically into the crista ethmoidalis. The middle portion attaches obliquely to the lamina papyracea. The posterior third attaches to the lamina papyracea as well, but horizontally.

- The fourth lamella is the superior turbinate.

The agger nasi cell is the most anterior of the anterior ethmoid cells.[15] It is found anterior and superior to the middle turbinate attachment to the lateral wall. The agger nasi cell's posterior wall forms the frontal recess's anterior wall. The ethmoid bulla is the largest of the anterior ethmoid cells above the infundibulum. The anterior ethmoid artery courses over the roof of this cell.

Embryology

Paranasal sinuses' development is heralded by the appearance of a series of folds on the lateral nasal wall at approximately the eighth week of gestation, known as the ethmoturbinals. Six to 7 folds emerge initially, but eventually, only 3 to 4 persist through regression and fusion.

- First ethmoturbinal: they are rudimentary and incomplete in humans. The ascending portion forms the agger nasi descending portion forms the uncinate process.

- Second ethmoturbinal: it forms the middle turbinate.

- Third ethmoturbinal: it forms the superior turbinate.

- Fourth and fifth ethmoturbinals: they fuse to form the supreme turbinate.

As development progresses, furrows form between these ethmoturbinals, establishing rudimentary meati and recesses. The frontal sinus originates from the anterior pneumatization of the frontal recess into the frontal bone. It does not appear until the age of 5 to 6. The sphenoid sinus develops during the third month of gestation. During this time, the nasal mucosa invaginates into the posterior portion of the cartilaginous nasal capsule to form a pouch-like cavity. The wall surrounding this cartilage is ossified in the later months of fetal development. Then, during the second and third years of life, the cartilage is resorbed, and the cavity becomes attached to the body of the sphenoid. By the sixth or seventh year of life, pneumatization of the sphenoid sinus progresses. By twelve years of age, the pneumatization is complete with pneumatization of the anterior clinoids and pterygoid process.[16] The maxillary sinus starts developing during the 10th week of intrauterine life.[2] The ethmoid infundibulum invaginations towards the mesenchyme fuse during the 11th week of development, forming 1 oval cavity with smooth walls – the primordium of the maxillary sinus.[23] The sinus ossification starts during the 16th week.[23] The maxillary sinus shows a biphasic growth pattern at 3 and 7 to 18 years of age. At birth, the ethmoid sinuses consist of 3 to 4 air cells. By the time an individual reaches adulthood, they consist of 1 to 15 aerated cells.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Branches of the maxillary artery irrigate the maxillary sinus: the infraorbital artery, the posterior superior alveolar artery, and the posterior lateral nasal artery.[24] The infraorbital artery travels through the infraorbital groove and canal and then through the infraorbital foramen.[24] The posterior superior alveolar artery runs along the sinus’ medial wall. The posterior lateral nasal artery can also be found within the medial wall of the maxillary sinus.[24] The maxillary sinus innervation is provided by branches of the maxillary nerve: middle, anterior, and posterior superior alveolar nerves and infraorbital nerve.[2] The frontal sinus vasculature consists of the supraorbital and supratrochlear arteries and ophthalmic and supraorbital veins. The sphenopalatine artery supplies the sphenoid sinus, and venous drainage is via the maxillary vein. The anterior and posterior ethmoid arteries supply the ethmoid sinuses, respectively. These arteries are branches of the ophthalmic artery, a branch of the internal carotid artery. The maxillary and ethmoid veins do ethmoid sinus venous drainage.

Nerves

The maxillary sinus innervation is provided by branches of the maxillary nerve: middle, anterior, and posterior superior alveolar nerves and infraorbital nerve.[2] The sphenopalatine nerve provides the sphenoid sinus innervation, which comprises parasympathetic fibers and CN V2. The frontal sinus is innervated by the supraorbital and supratrochlear nerves (CNV1). The anterior and posterior ethmoid nerves provide innervation to ethmoid sinuses.

Muscles

The frontalis muscle runs over the frontal skull and sinus region and is part of the mechanism of facial expression. The levator muscles of the lips are anchored over the maxillary sinuses. The zygomatic projection of the maxilla is part of the anchorage of the masseter muscle, a powerful jaw closure.

Physiologic Variants

Nasal anatomy differs significantly among individuals, and certain anatomic variations are relatively common. These variations may contribute to mechanical obstruction of the stomatal complex, leading to rhinosinusitis. Concha bullosa is defined as aeration of the middle turbinate.[4] This variation can be either unilateral or bilateral. If large, a concha bullosa may obstruct the middle meatus or infundibulum. The nasal septal deviation is an asymmetric bowing of the nasal cartilaginous septum. Such bowing may laterally compress the middle turbinate, leading to the narrowing of the middle meatus. This variation is often congenital but may also be secondary to nasal trauma. The middle turbinate usually curves medially toward the nasal septum. However, the resultant anatomic variant is known as a paradoxical middle turbinate when the turbinate curves laterally. Such a variant can narrow or obstruct the nasal cavity, middle meatus, or infundibulum. The uncinate process is a structure that has multiple variations between individual patients. The superior attachment of the uncinate process has 3 major variations that help determine the anatomic configuration of the frontal recess and its drainage:

- An uncinate process that extends laterally to attach to the lamina papyracea or the ethmoid bulla, forming a terminal recess of the infundibulum with the frontal recess opening directly into the middle meatus

- An uncinate process that extends medially and attaches to the lateral surface of the middle turbinate, with the frontal recess draining into the infundibulum

- An uncinate process that extends medially and superiorly to directly attached to the skull base, with the frontal recess draining into the infundibulum

- Eighty percent of the time, the uncinate attaches to the lamina papyracea, resulting in frontal sinus drainage medial to the uncinate, while 20% of the time, the uncinate attaches to either the skull base or middle turbinate, resulting in drainage lateral to the uncinate.

Haller cells are ethmoid air cells extending laterally over the medial aspect of the maxillary sinus roof. If large enough, they may cause narrowing of the infundibulum. Onodi cells are lateral and posterior extensions of the posterior ethmoid cells. Horizontal septations around the sphenoid sinus delineate them. Importantly, these cells may surround the optic nerve tract, increasing the risk of injury to the optic nerve during surgery. Lastly, the height of the ethmoid roof can vary between patients and between each side in the same patient. When the ethmoid roof height is asymmetric in a patient, the risk of intracranial penetration during FESS is higher. These are only a few of the anatomic variations seen in sinonasal anatomy. While they represent the most common variations, a sound understanding of tridimensional anatomy is paramount to safe and effective endoscopic sinus surgery.

Clinical Significance

Paranasal sinuses are prone to inflammation and infection. When they become blocked from secretions or a mass, mucus drainage is interrupted, causing sinusitis. Depending on the cause, sinusitis is treated with corticosteroids, decongestants, nasal irrigation, and hydration. Rarely, surgical intervention is required to enhance drainage. Malignancies of the paranasal sinuses are rare. The majority of cancers occur in the maxillary sinus and are more common in men than women. Maxillary sinus malignancies occur between ages 45 and 70, and the most frequent is a sarcoma. Even though metastases are rare, these malignancies are locally invasive and destructive. Diagnosis is delayed in most cases, and the prognosis is poor.

Acute and chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) are symptomatic nose and paranasal sinus inflammation. The 2 are distinguished based on the duration of the complaints. Generally speaking, acute rhinosinusitis is widely considered to be an infectious disorder. On the other hand, chronic rhinosinusitis is typically defined as an inflammatory disorder. In acute rhinosinusitis, the underlying etiology is usually viral or bacterial and occasionally fungal. Its pathogenesis involves infection followed by tissue invasion. The most widely accepted classification system divides chronic rhinosinusitis into chronic rhinosinusitis with and without nasal polyps based on nasal endoscopy (CRSwNP and CRSsNP, respectively).[25] Initially, it was believed that CRSsNP was a disease process characterized by persistent inflammation resulting in an incomplete resolution of acute rhinosinusitis. CRSwNP, on the other hand, was thought to be a noninfectious disease process with unclear etiology, perhaps related to atopy. Instead, current research has revealed that the etiology and pathogenesis of either form of CRS are much more complex.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Ogle OE, Weinstock RJ, Friedman E. Surgical anatomy of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses. Oral and maxillofacial surgery clinics of North America. 2012 May:24(2):155-66, vii. doi: 10.1016/j.coms.2012.01.011. Epub 2012 Mar 2 [PubMed PMID: 22386856]

Iwanaga J, Wilson C, Lachkar S, Tomaszewski KA, Walocha JA, Tubbs RS. Clinical anatomy of the maxillary sinus: application to sinus floor augmentation. Anatomy & cell biology. 2019 Mar:52(1):17-24. doi: 10.5115/acb.2019.52.1.17. Epub 2019 Mar 29 [PubMed PMID: 30984447]

Vaid S, Vaid N. Normal Anatomy and Anatomic Variants of the Paranasal Sinuses on Computed Tomography. Neuroimaging clinics of North America. 2015 Nov:25(4):527-48. doi: 10.1016/j.nic.2015.07.002. Epub 2015 Aug 20 [PubMed PMID: 26476378]

Reddy UD, Dev B. Pictorial essay: Anatomical variations of paranasal sinuses on multidetector computed tomography-How does it help FESS surgeons? The Indian journal of radiology & imaging. 2012 Oct:22(4):317-24. doi: 10.4103/0971-3026.111486. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23833424]

Chanavaz M. Maxillary sinus: anatomy, physiology, surgery, and bone grafting related to implantology--eleven years of surgical experience (1979-1990). The Journal of oral implantology. 1990:16(3):199-209 [PubMed PMID: 2098563]

Przystańska A, Kulczyk T, Rewekant A, Sroka A, Jończyk-Potoczna K, Lorkiewicz-Muszyńska D, Gawriołek K, Czajka-Jakubowska A. Introducing a simple method of maxillary sinus volume assessment based on linear dimensions. Annals of anatomy = Anatomischer Anzeiger : official organ of the Anatomische Gesellschaft. 2018 Jan:215():47-51. doi: 10.1016/j.aanat.2017.09.010. Epub 2017 Sep 28 [PubMed PMID: 28963046]

Scarfe WC, Langlais RP, Ohba T, Kawamata A, Maselle I. Panoramic radiographic patterns of the infraorbital canal and anterior superior dental plexus. Dento maxillo facial radiology. 1998 Mar:27(2):85-92 [PubMed PMID: 9656872]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRoberti F, Boari N, Mortini P, Caputy AJ. The pterygopalatine fossa: an anatomic report. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2007 May:18(3):586-90 [PubMed PMID: 17538322]

Whyte A, Boeddinghaus R. The maxillary sinus: physiology, development and imaging anatomy. Dento maxillo facial radiology. 2019 Dec:48(8):20190205. doi: 10.1259/dmfr.20190205. Epub 2019 Aug 13 [PubMed PMID: 31386556]

Eberhardt JA, Torabinejad M, Christiansen EL. A computed tomographic study of the distances between the maxillary sinus floor and the apices of the maxillary posterior teeth. Oral surgery, oral medicine, and oral pathology. 1992 Mar:73(3):345-6 [PubMed PMID: 1545967]

Lee WJ, Lee SJ, Kim HS. Analysis of location and prevalence of maxillary sinus septa. Journal of periodontal & implant science. 2010 Apr:40(2):56-60. doi: 10.5051/jpis.2010.40.2.56. Epub 2010 Apr 15 [PubMed PMID: 20498761]

Krennmair G, Ulm CW, Lugmayr H, Solar P. The incidence, location, and height of maxillary sinus septa in the edentulous and dentate maxilla. Journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery : official journal of the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. 1999 Jun:57(6):667-71; discussion 671-2 [PubMed PMID: 10368090]

Coemert S, Roth R, Strauss G, Schmitz PM, Lueth TC. A handheld flexible manipulator system for frontal sinus surgery. International journal of computer assisted radiology and surgery. 2020 Sep:15(9):1549-1559. doi: 10.1007/s11548-020-02220-0. Epub 2020 Jul 1 [PubMed PMID: 32613601]

Saini AT, Govindaraj S. Evaluation and Decision Making in Frontal Sinus Surgery. Otolaryngologic clinics of North America. 2016 Aug:49(4):911-25. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2016.03.015. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27450615]

Wormald PJ, Hoseman W, Callejas C, Weber RK, Kennedy DW, Citardi MJ, Senior BA, Smith TL, Hwang PH, Orlandi RR, Kaschke O, Siow JK, Szczygielski K, Goessler U, Khan M, Bernal-Sprekelsen M, Kuehnel T, Psaltis A. The International Frontal Sinus Anatomy Classification (IFAC) and Classification of the Extent of Endoscopic Frontal Sinus Surgery (EFSS). International forum of allergy & rhinology. 2016 Jul:6(7):677-96. doi: 10.1002/alr.21738. Epub 2016 Mar 14 [PubMed PMID: 26991922]

Özer CM, Atalar K, Öz II, Toprak S, Barut Ç. Sphenoid Sinus in Relation to Age, Gender, and Cephalometric Indices. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2018 Nov:29(8):2319-2326. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000004869. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30320684]

Fujioka M, Young LW. The sphenoidal sinuses: radiographic patterns of normal development and abnormal findings in infants and children. Radiology. 1978 Oct:129(1):133 [PubMed PMID: 693864]

Cashman EC, Macmahon PJ, Smyth D. Computed tomography scans of paranasal sinuses before functional endoscopic sinus surgery. World journal of radiology. 2011 Aug 28:3(8):199-204. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v3.i8.199. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22022638]

Štoković N, Trkulja V, Dumić-Čule I, Čuković-Bagić I, Lauc T, Vukičević S, Grgurević L. Sphenoid sinus types, dimensions and relationship with surrounding structures. Annals of anatomy = Anatomischer Anzeiger : official organ of the Anatomische Gesellschaft. 2016 Jan:203():69-76. doi: 10.1016/j.aanat.2015.02.013. Epub 2015 Mar 20 [PubMed PMID: 25843780]

Davis WE, Templer J, Parsons DS. Anatomy of the paranasal sinuses. Otolaryngologic clinics of North America. 1996 Feb:29(1):57-74 [PubMed PMID: 8834272]

Stammberger HR, Kennedy DW, Anatomic Terminology Group. Paranasal sinuses:anatomic terminology and nomenclature. The Annals of otology, rhinology & laryngology. Supplement. 1995 Oct:167():7-16 [PubMed PMID: 7574267]

Lafci Fahrioglu S, VanKampen N, Andaloro C. Anatomy, Head and Neck, Sinus Function and Development. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30422521]

Nuñez-Castruita A, López-Serna N, Guzmán-López S. Prenatal development of the maxillary sinus: a perspective for paranasal sinus surgery. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2012 Jun:146(6):997-1003. doi: 10.1177/0194599811435883. Epub 2012 Jan 20 [PubMed PMID: 22267494]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFlanagan D. Arterial supply of maxillary sinus and potential for bleeding complication during lateral approach sinus elevation. Implant dentistry. 2005 Dec:14(4):336-8 [PubMed PMID: 16361882]

Stevens WW, Schleimer RP, Kern RC. Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyps. The journal of allergy and clinical immunology. In practice. 2016 Jul-Aug:4(4):565-72. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2016.04.012. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27393770]