Introduction

Papilledema is a disease entity that refers to the swelling of the optic disc due to elevated intracranial pressure (ICP). This term should be distinguished from disc edema which specifies a broader category of optic disc swelling secondary to other etiologies. Also, it is worth noting that ICP may elevate in the absence of optic disc swelling. Papilledema is usually seen bilaterally but can be seen asymmetrically and rarely unilaterally. It can be an alarming sign for disease entities that cause elevated ICP such as brain tumors, cerebrospinal inflammation (infectious and non-infectious), and idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH).[1]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The etiologies for papilledema are those that raise intracranial pressure. The Monro-Kellie hypothesis describes ICP as a function of its total volume of blood, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and brain parenchyma within the fixed cranial space. As the volume within the intracranial space goes up, a corresponding decrease in volume from another intracranial component must go down which can be seen with both clinical and radiologic manifestations such as a headache and decreased cerebral blood flow. Inadequate compensation for this can result in high ICP and can be seen in the following scenarios: space-occupying lesion such as tumor or hemorrhage, increase in CSF such as from obstructive hydrocephalus, increase in blood volume such as from venous sinus thrombosis, or by idiopathic intracranial hypertension.[2]

Epidemiology

The frequency in which papilledema varies depending on the particular study and setting in which it is documented. In the eye care professional's office, it most often results from idiopathic intracranial hypertension of which the annual incidence is estimated to be 0.9 per 100000 in the United State's general population. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension is seen to be most prevalent in obese women of childbearing age with an incidence in obese women aged 20 to 44 found to be 13 per 100000. This disease has not been found to have a racial predilection and much less frequently affects men, children, and older persons.[3]

Pathophysiology

The optic nerve, comprised of retinal ganglion cell axons and glial cells, is sheathed in all three meningeal layers and is continuous with the subarachnoid space of the brain. Intracranial CSF is by this way contiguous with the CSF surrounding the optic nerve allowing elevated ICP to be transmitted directly to the optic nerve. The thinking is that this disrupts the normal pressure gradient across the intraocular and orbital optic nerve causing retrograde axoplasmic flow across the optic disc which results in disc edema and optic neuropathy. There are competing theories as to whether this is due to mechanical compression or ischemic insult to axons.[4]

History and Physical

A thorough history documenting a patient's visual complaints and underlying etiology of elevated ICP is necessary. Patients may experience visual field loss and transient dim-outs. Elevated ICP may result in horizontal binocular diplopia from an abducens nerve palsy, and audible vascular bruits known as pulsatile tinnitus. A headache is common and may worsen with positions that place the dependent flow of volume to the intracranial space. Nausea and vomiting may also be present with acute rises in ICP. Medications such as steroids, retinoids, tetracyclines, oral contraceptives should be asked about as causes of ICP elevation. Weight gain and obesity should also undergo assessment as risk factors for idiopathic intracranial hypertension.

A standard ophthalmic and neurologic exam should be performed with attention to detail of the optic disc. The lack of spontaneous venous pulsations at the disc is a sign of elevated ICP when it has exceeded the intraocular pressure. An exam may reveal an elevated optic disc, dilated veins, hemorrhages overlying the disc, hyperemia of the disc, and peripapillary retinal folds known as Paton lines. The disc margins become blurred, and a reproducible inter-observer grading scheme suggested by ophthalmologist Lars Friesen is widely utilized[5][6]:

- Grade 1: Disruption of the normal radial arrangement of nerve fiber bundles with a blurring of the nasal border of the optic disc and normal temporal margin

- Grade 2: Nasal and temporal (circumferential) blurring of the optic disc with more pronounced changes from grade 1

- Grade 3: The elevated and blurred disc margin borders obscure one or more major retinal vessel segments

- Grade 4: More pronounced changes than from grade 3 and with total obscuration of a segment of the central retinal artery or vein

- Grade 5: More pronounced changes than from grade 4 and with total obscuration of all disc vessels

Evaluation

The evaluation of papilledema points towards identifying the underlying etiology however initial workup should at least include contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging of brain and orbits as well as magnetic resonance venography to respectively search for mass or venous sinus thrombosis. If deemed safe after imaging to assess the risk of herniation, a lumbar puncture may be performed to document ICP by measuring opening pressure (in left lateral decubitus position: normal less than 25 cm H20). Cerebrospinal fluid studies to analyze protein, glucose, cell count and differential, and cultures are also diagnostic.[1]

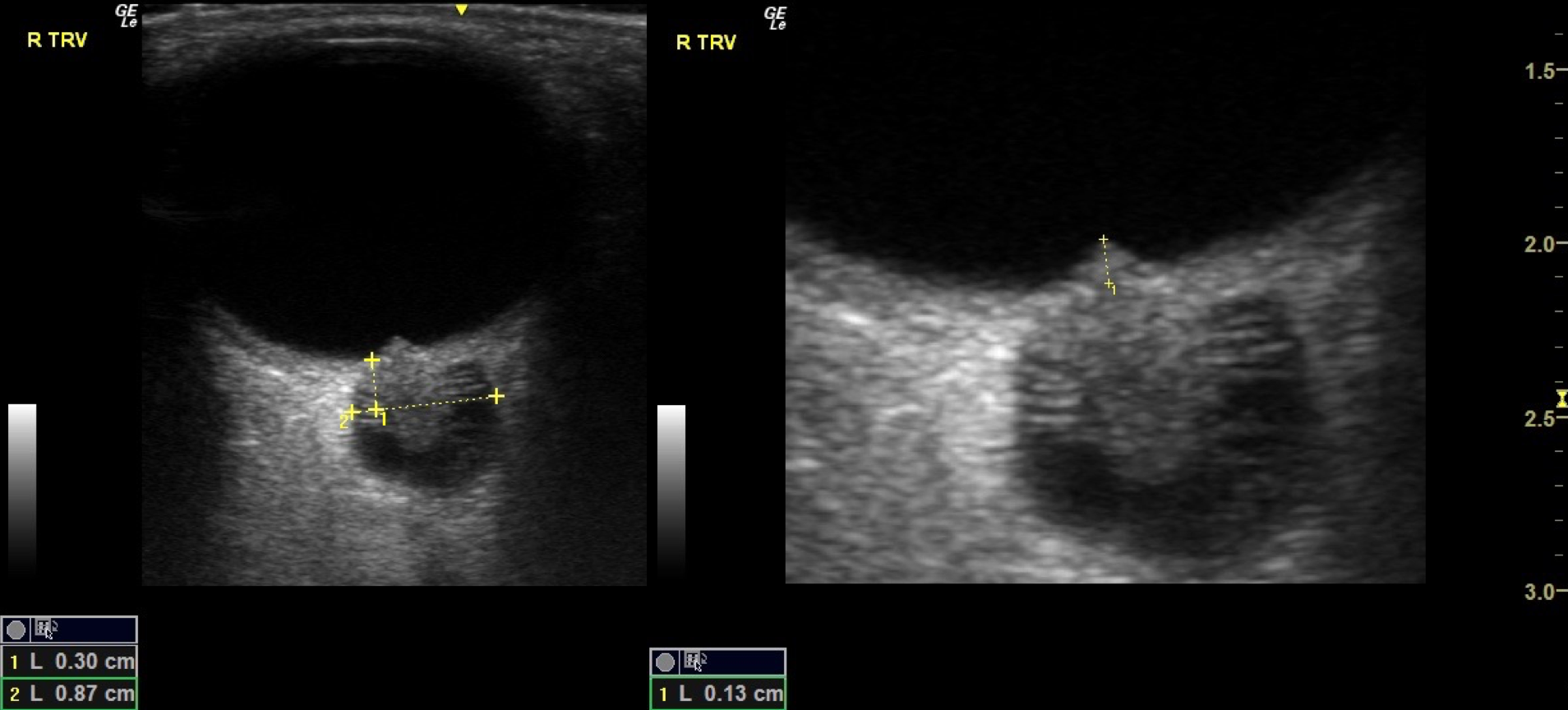

Formal perimetry should be performed to document and monitor for potential visual field loss. Fluorescein angiography and B-scan ultrasound can also be utilized to identify other causes for disc edema or conditions which may resemble papilledema.

Treatment / Management

The treatment for papilledema is aimed at addressing the cause of raised ICP. In cases of mass, surgical treatment may be indicated. Venous sinus thrombosis may prompt workup of precipitating factors and secondary prevention with anticoagulation.[7] In patients with appropriate workup and documented high ICP where no structural or other localizing causes are present, the term idiopathic intracranial hypertension is applied, and the patient’s symptoms management is with acetazolamide and weight loss. Surgical measures such as optic nerve sheath fenestration are considered when vision is thought to be severely threatened. Ventriculoperitoneal and lumboperitoneal shunts are other surgical interventions that can reduce ICP by draining CSF. Venous sinus stenting is considered in patients with IIH where significant transverse venous sinus stenosis is observed.[1](B2)

Differential Diagnosis

Other causes of optic disc edema such as from intraocular inflammation, central retinal vein occlusion, compressive optic neuropathy, optic neuritis, diabetic papillopathy, and ischemic optic neuropathy should be distinguished.

Pseudopapilledema also presents with elevated optic nerve head appearance and blurred margins. It may be a result of congenital dysplasia, optic disc drusen, or tilted optic disc.

Prognosis

The prognosis for papilledema is related to the chronicity of the disease. Chronically high ICP can lead to permanent drop out of the nerve fiber layer which can result in progressive visual field loss and loss of central visual acuity.

Complications

Complications can arise from inadequately treated underlying ICP. This lack of treatment can result from failure to recognize elevated ICP or from surgical failure. Failure of optic nerve sheath fenestration can occur due to subsequent scarring, and CSF shunts may fail by way of malfunction, obstruction, or blockage. Surgery of any type, particularly surgery accessing the cerebrospinal space poses a risk for severe infection.

Pearls and Other Issues

Disc edema is often identified in the clinic setting and can variably be a sign of life-threatening or vision-threatening conditions. The practitioner should not hesitate to expedite a patient's workup by admission to the hospital and aggressive treatment if the patient presents with poor central visual acuity, high-grade disc edema, and a greater frequency of transient visual obscurations. Additionally, patients with history concerning for underlying cancer or systemic symptoms should be admitted hospitalized for further workup.[8]

As mentioned before, elevated ICP can also occur in the absence of disc edema. The only way to accurately gauge ICP is by direct measurement. Also, an optic nerve that has undergone atrophy and loss of axons will be less susceptible to becoming edematous with repeated bouts of ICP elevation.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The eye care professional should be familiar with the appearance and evaluation of the optic disc as well as in obtaining a pertinent history and physical. A timely workup is a priority, and the appropriate specialist referrals should be made. Optimization of patient care and safety occurs when communication between referring and co-managing healthcare providers is precise and efficient. For example, the ophthalmologist observing the need for surgical intervention for idiopathic intracranial hypertension should be in communication with neurosurgery regarding appropriate intervention. Patient autonomy is preserved when presented with risks, benefits, and alternatives provided by different disciplines such as in the case of optic nerve sheath fenestration versus ventriculoperitoneal shunt.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Rigi M, Almarzouqi SJ, Morgan ML, Lee AG. Papilledema: epidemiology, etiology, and clinical management. Eye and brain. 2015:7():47-57. doi: 10.2147/EB.S69174. Epub 2015 Aug 17 [PubMed PMID: 28539794]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMokri B. The Monro-Kellie hypothesis: applications in CSF volume depletion. Neurology. 2001 Jun 26:56(12):1746-8 [PubMed PMID: 11425944]

Chen J, Wall M. Epidemiology and risk factors for idiopathic intracranial hypertension. International ophthalmology clinics. 2014 Winter:54(1):1-11. doi: 10.1097/IIO.0b013e3182aabf11. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24296367]

Trobe JD. Papilledema: the vexing issues. Journal of neuro-ophthalmology : the official journal of the North American Neuro-Ophthalmology Society. 2011 Jun:31(2):175-86. doi: 10.1097/WNO.0b013e31821a8b0b. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21593630]

Jacks AS, Miller NR. Spontaneous retinal venous pulsation: aetiology and significance. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 2003 Jan:74(1):7-9 [PubMed PMID: 12486256]

Frisén L. Swelling of the optic nerve head: a staging scheme. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 1982 Jan:45(1):13-8 [PubMed PMID: 7062066]

Sader N, de Lotbinière-Bassett M, Tso MK, Hamilton M. Management of Venous Sinus Thrombosis. Neurosurgery clinics of North America. 2018 Oct:29(4):585-594. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2018.06.011. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30223971]

Wall M,Falardeau J,Fletcher WA,Granadier RJ,Lam BL,Longmuir RA,Patel AD,Bruce BB,He H,McDermott MP,NORDIC Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension Study Group., Risk factors for poor visual outcome in patients with idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Neurology. 2015 Sep 1 [PubMed PMID: 26245929]