Introduction

In the 1940s, cervical cancer was a leading cause of death for women of childbearing age in the United States. Dr George Papanicolaou, a Greek immigrant, initially began his academic career studying the reproductive cycles of guinea pigs. After moving to the United States, he held a position in the anatomy department at Cornell University. He changed his focus of study to human physiology and began collaborating with gynecological pathologist Dr Herbert Traut. While working together at Cornell University, they published Diagnosis of Uterine Cancer by the Vaginal Pap Smear in 1943. This significant work detailed how normal and abnormal vaginal and cervical cells could be observed under a microscope and how they should be classified. Shortly thereafter, the Pap smear became the gold standard in cervical cancer screening and remains the primary screening tool for cervical cancer today.[1][2][3][4]

Etiology and Epidemiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology and Epidemiology

In the United States, the death rate due to cervical cancer has declined by more than 60% since the 1950s. In the past, cervical cancer was one of the most common cancers affecting women of childbearing age, but over time, its occurrence has significantly decreased. Today, it ranks as the 14th most common cancer among these women, indicating a marked reduction in both incidence and impact.

In 2010, approximately 12,000 women were diagnosed with cervical cancer, resulting in approximately 4000 deaths. Between 2002 and 2012, the rate of cervical cancer decreased by 1.3%, and deaths from cervical cancer decreased by 0.9%. In 2014, Hispanic women were reported to have the highest rate of cervical cancer diagnoses, whereas African-American women had the highest death rate from the disease.[5][6][7]

Cervical cancer is much more common in countries without widespread screening programs. More than 80% of cervical cancer cases are found in developing countries. Cervical cancer is still the third most common cause of cancer in women worldwide. Annually, there are approximately 528,000 new cases of cervical cancer, with 266,000 deaths. These statistics make it the second most common cause of cancer-related death in women.

Pathophysiology

In the 1980s, researchers discovered that nearly all cervical cancer cases were caused by human papillomavirus (HPV). There are more than 100 types of HPV, and 40 can be transmitted sexually, whereas 15 are considered high-risk HPV or cancer-causing. There are 2 subtypes of HPV—HPV 16 and 18, which are responsible for about 70% of cervical cancers worldwide.

Cervical infection with high-risk HPV is typically required for the development of cervical cancer. However, HPV infection alone is not sufficient for progression to neoplasia. Most infections with high-risk HPV are transient and do not progress to cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN). A small percentage of women infected with high-risk HPV develop cervical cancer. Cigarette smoking, a weakened immune system, and HIV infection are all factors contributing to the persistence of HPV.[8][9][10][11]

Specimen Requirements and Procedure

In 2009, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommended that women begin Pap smear screenings at 21. The ACOG also advises that women aged 21 to 29 undergo Pap smear testing every 3 years. For women aged 30 to 65, the ACOG recommends Pap smears with HPV testing every 5 years. Screening can generally be discontinued after 65. However, certain groups of women should be screened more frequently for cervical cancer compared to the general population, which include women infected with HIV; immunocompromised women, such as organ transplant patients; women exposed to diethylstilbestrol while in utero; and those previously treated for CIN 2, CIN 3, or cervical cancer.

In 2018, the United States Preventive Services Task Force revised its guidelines as follows:

- Grade A recommendation: Screening for cervical cancer every 3 years with cervical cytology alone in women aged 21 to 29.

- Grade A recommendation: Screening every 3 years with cervical cytology alone, every 5 years with hrHPV testing alone, or every 5 years with hrHPV testing combined with cytology (co-testing) in women aged 30 to 65.

- Grade D recommendation: No screening for cervical cancer in women younger than 21.

- Grade D recommendation: No screening for cervical cancer in women older than 65 who have had adequate prior screening and are not otherwise at high risk for the disease.

- Grade D recommendation: Screening for cervical cancer in women who have had a hysterectomy with removal of the cervix and do not have a history of a high-grade precancerous lesion or cervical cancer.

Diagnostic Tests

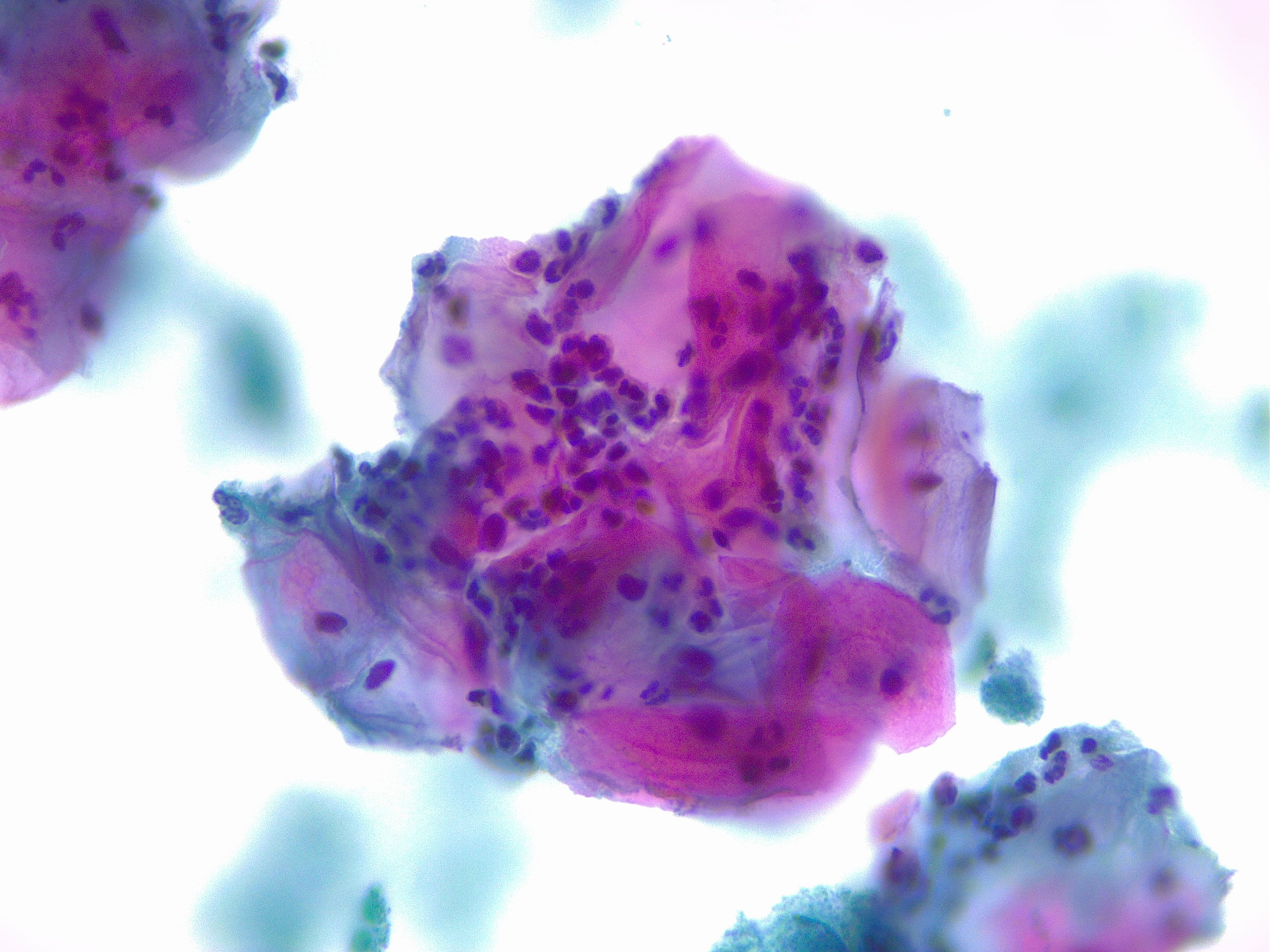

Women with epithelial cell abnormalities on Pap smear should be further tested with colposcopy and biopsy (see Image. Squamous Cells with Acute Inflammation). A colposcope is a binocular microscope that allows visual inspection of the cervix. Gross abnormalities visualized on colposcopy can then be biopsied for further classification.

Testing Procedures

There are 2 acceptable techniques for collecting the Pap smear—liquid-based and conventional. In both methods, a clinician inserts a speculum into the woman's vagina and identifies the cervix. The liquid-based method involves collecting cells from the transformation zone of the cervix using a brush and transferring the cells to a vial of liquid preservative. The conventional technique involves collecting cells from the transformation zone of the cervix using a brush and spatula, transferring the cells to a slide, and fixing the slide with a preservative. The liquid-based technique allows testing for HPV, gonorrhea, and chlamydia from a single collection. Theoretically, the liquid-based technique has the advantages of more straightforward interpretation, fewer unsatisfactory results, and the filtration of blood and debris.

Interfering Factors

Vaginal discharge, blood, and lubricants can interfere with the interpretation of Pap smears. When performing Pap smears, many healthcare professionals use water or a small amount of water-based lubricant to minimize patient discomfort.

Results, Reporting, and Critical Findings

Bethesda System for Reporting Cervical Cytology

The Bethesda System for Reporting Cervical Cytology is a standardized classification system used in the United States for interpreting Pap smear results and has been in place since 1988. The most recent update was made in 2014. This system provides clear guidelines for reporting and interpreting cervical cytology findings, which aids in the management and diagnosis of cervical abnormalities.

Components of the Bethesda system:

- Specimen type: Indicates whether the sample is conventional or liquid-based

- Specimen adequacy: Indicates whether the specimen is satisfactory or unsatisfactory for evaluation

- General categorization

- Negative for intraepithelial lesion or malignancy

- Other

- Epithelial cell abnormality

- Interpretation/results:

- Negative intraepithelial lesion: No cellular evidence of neoplasia)

- Nonneoplastic findings: Includes non-neoplastic cellular variations, reactive cellular changes, and glandular cells in post-hysterectomy

- Organisms: Detection of Trichomonas vaginalis, bacterial vaginosis, Candida species, Actinomyces species, and cellular changes consistent with herpes virus and cytomegalovirus

- Other

- Endometrial cells in a woman older than 45

Epithelial cell abnormalities:

- Squamous cell:

- Atypical squamous cells (ASCs)

- ASCs of undetermined significance (ASC-US)

- Cannot exclude high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (ASC-H)

- Low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion: Mild dysplasia or CIN 1

- High-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion: Moderate and severe dysplasia, corresponding to CIN 2 and CIN 3

- With features suspicious for invasion if invasion is suspected

- Squamous cell carcinoma

- Atypical squamous cells (ASCs)

- Glandular cell:

- Endocervical cells (not otherwise specified)

- Endometrial cells (not otherwise specified)

- Glandular cells (not otherwise specified)

- Endocervical cells favor neoplastic

- Glandular cells favor neoplastic

- Endocervical adenocarcinoma in situ

- Adenocarcinoma endocervical

- Endometrial

- Extrauterine

- Not otherwise specified

- Other malignant neoplasms

Clinical Significance

Since the discovery of HPV subtypes causing most cervical cancer cases, 2 vaccines have been developed to reduce the incidence of new cervical cancer cases. The bivalent vaccine offers protection against HPV subtypes 16 and 18, whereas the quadrivalent vaccine provides protection not only against HPV 16 and 18 but also for subtypes 6 and 11, which cause 90% of genital warts. Ongoing research continues to focus on developing vaccines for the prevention of cervical cancer.

Quality Control and Lab Safety

A computer-aided automated device can interpret Pap smear specimens. When using a computer-aided system, the Bethesda System for Reporting Cervical Cytology requires documentation of the device and its results.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The interprofessional team plays a vital role in improving patient care and outcomes related to Pap smears. This collaborative approach involves various healthcare professionals, including gynecologists, primary care physicians, nurses, pathologists, and laboratory technicians. Each member contributes unique expertise, enhancing the quality of care provided to patients.

Collaboration begins with clear communication among team members regarding screening guidelines, patient history, and individual risk factors for cervical cancer. Regular interdisciplinary meetings allow the team to review and discuss cases, share insights on interpreting Pap smear results, and develop shared protocols for follow-up care based on findings.

In addition, ongoing interprofessional continuing education initiatives allow healthcare professionals to stay updated on best practices and emerging evidence. This shared learning experience fosters an environment where each team member understands their role in the care continuum and the importance of their contributions. By recognizing and valuing each team member's contributions, the interprofessional team can effectively flatten the hierarchy in healthcare, leading to improved patient outcomes and a more integrated approach to cervical cancer prevention and care.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Sanford NN, Sher DJ, Butler S, Xu X, Ahn C, D'Amico AV, Rebbeck T, Aizer AA, Mahal BA. Cancer Screening Patterns Among Current, Former, and Never Smokers in the United States, 2010-2015. JAMA network open. 2019 May 3:2(5):e193759. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.3759. Epub 2019 May 3 [PubMed PMID: 31099863]

Nogueira-Rodrigues A. HPV Vaccination in Latin America: Global Challenges and Feasible Solutions. American Society of Clinical Oncology educational book. American Society of Clinical Oncology. Annual Meeting. 2019 Jan:39():e45-e52. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_249695. Epub 2019 May 17 [PubMed PMID: 31099692]

Ge Y, Mody RR, Olsen RJ, Zhou H, Luna E, Armylagos D, Puntachart N, Hendrickson H, Schwartz MR, Mody DR. HPV status in women with high-grade dysplasia on cervical biopsy and preceding negative HPV tests. Journal of the American Society of Cytopathology. 2019 May-Jun:8(3):149-156. doi: 10.1016/j.jasc.2019.01.001. Epub 2019 Jan 14 [PubMed PMID: 31097291]

Niu S, Molberg K, Thibodeaux J, Rivera-Colon G, Hinson S, Zheng W, Lucas E. Challenges in the Pap diagnosis of endocervical adenocarcinoma in situ. Journal of the American Society of Cytopathology. 2019 May-Jun:8(3):141-148. doi: 10.1016/j.jasc.2018.12.004. Epub 2018 Dec 31 [PubMed PMID: 31097290]

Rukhadze L, Lunet N, Peleteiro B. Cervical cytology use in Portugal: Results from the National Health Survey 2014. The journal of obstetrics and gynaecology research. 2019 Jul:45(7):1286-1295. doi: 10.1111/jog.13974. Epub 2019 Apr 29 [PubMed PMID: 31034140]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSwailes AL, Hossler CE, Kesterson JP. Pathway to the Papanicolaou smear: The development of cervical cytology in twentieth-century America and implications in the present day. Gynecologic oncology. 2019 Jul:154(1):3-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2019.04.004. Epub 2019 Apr 15 [PubMed PMID: 30995961]

Corkum MT, Shaddick H, Jewlal E, Patil N, Leung E, Sugimoto A, McGee J, Prefontaine M, D'Souza D. When Pap Testing Fails to Prevent Cervix Cancer: A Qualitative Study of the Experience of Screened Women Under 50 with Advanced Cervix Cancer in Canada. Cureus. 2019 Jan 24:11(1):e3950. doi: 10.7759/cureus.3950. Epub 2019 Jan 24 [PubMed PMID: 30937248]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceStumbar SE, Stevens M, Feld Z. Cervical Cancer and Its Precursors: A Preventative Approach to Screening, Diagnosis, and Management. Primary care. 2019 Mar:46(1):117-134. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2018.10.011. Epub 2018 Dec 22 [PubMed PMID: 30704652]

Santamaría-Ulloa C, Valverde-Manzanares C. Inequality in the Incidence of Cervical Cancer: Costa Rica 1980-2010. Frontiers in oncology. 2018:8():664. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00664. Epub 2019 Jan 10 [PubMed PMID: 30687639]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceChrysostomou AC, Stylianou DC, Constantinidou A, Kostrikis LG. Cervical Cancer Screening Programs in Europe: The Transition Towards HPV Vaccination and Population-Based HPV Testing. Viruses. 2018 Dec 19:10(12):. doi: 10.3390/v10120729. Epub 2018 Dec 19 [PubMed PMID: 30572620]

Jin J. Screening for Cervical Cancer. JAMA. 2018 Aug 21:320(7):732. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.11365. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30140878]