Introduction

Osteoid osteoma was first described by Jaffe in 1935 and accounts for 10% of all benign bone tumors.[1] It is neither locally aggressive nor does it have the potential for malignant transformation. This bone tumor frequently affects the long bones of the femur and tibia. This chapter will focus on osteoid osteomas affecting the foot and ankle. The foot is less commonly affected (2-10%) with the talus being most commonly involved.[2] An osteoid osteoma presents with a nidus of vascular osteoid with surrounding sclerotic bone. Osteoid osteomas do not exceed a diameter of 2 cm and classify into cortical, cancellous, and subperiosteal subtypes.

Osteoid osteomas that occur in long bones are predominantly intracortical. The majority of osteoid osteomas that present in the foot exhibit minimal periosteal reaction and are of the cancellous and subperiosteal subtypes. The size of the nidus is used to differentiate an osteoid osteoma from an osteoblastoma. Osteoblastomas are typically greater than 2 cm.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The etiology of osteoid osteomas remains uncertain. Some believe it is a benign neoplasm while others maintain it is due to trauma or an inflammatory process.

Epidemiology

Osteoid osteomas account for 10% of benign bone tumors.[2] Typically an osteoid osteoma is found in individuals between the ages of 5 and 25 years of age with males three times more likely to be affected.[3][4]

Pathophysiology

A few hypotheses exist regarding the pathophysiology of osteoid osteomas. One proposal is that the formation of the tumor may be due to neoplasia or is the result of prior trauma to the area.[2] Although a history of trauma has been evident in one-third of documented cases, further research is warranted to explore the relationship.[5] Nerve fibers have been identified within the nidus by special immunohistochemical techniques and concentrate within the area of sclerosis surrounding the nidus.[6] Nerve fibers are stimulated by increased blood flow to the area from the release of prostaglandins. Studies have shown prostaglandin levels to be 100 to 1000 times more than levels found in normal bone, resulting in localized pain to the area.[6]

Histopathology

Microscopically, the central nidus is comprised of highly vascularized bone and intertwined osteoid. Remodeling of the bone occurs through osteoblastic activity. In the periphery of the nidus, an area of lucency is visible due to resorption of bone from osteoclastic activity. New bone formation occurs around the nidus and appears as sclerotic bone.

History and Physical

Intermittent, localized pain exacerbated at night and relieved by aspirin or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs) is the most common complaint of a patient suffering from an osteoid osteoma. Swelling is the next most common symptom and is thought to be due to the increased vascular supply to the tumor from prostaglandin release within the nidus. Other symptoms include bone deformity, muscle atrophy, and gait disturbances. If the tumor is intra-articular or located close to a joint, synovitis, effusion, arthritic changes, and contractures may be present. Osteoid osteomas that affect the femur and tibia have been shown to cause a limb length discrepancy. In a study of 4 patients, the affected limb was longer than the unaffected limb. The authors postulated this was likely the result of increased blood supply to a lesion close to an open growth plate.[7]

Evaluation

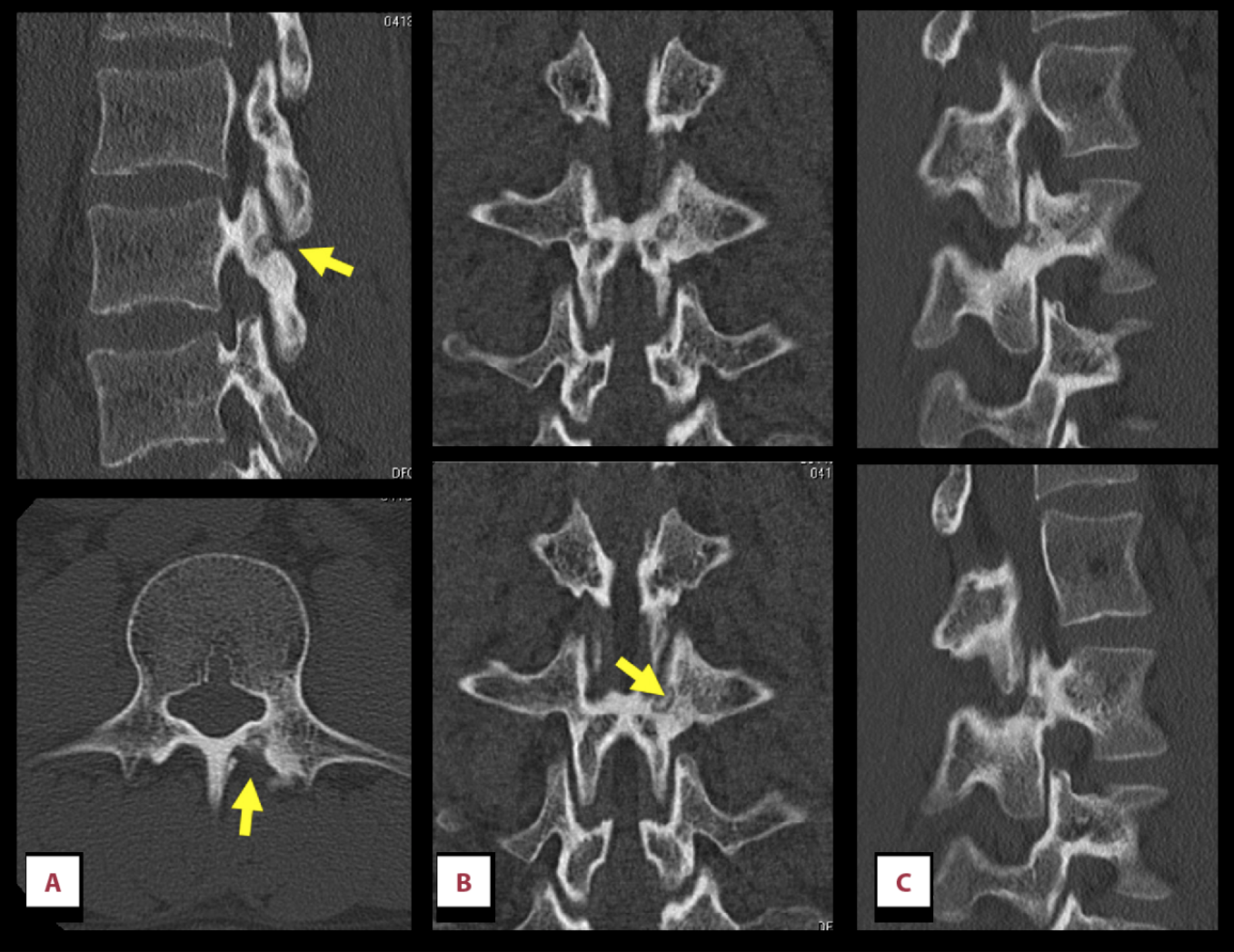

As with any other bone tumor, plain radiography is the initial exam of choice. The appearance of an osteoid osteoma on plain film is classically a small, round, radiolucent nidus with surrounding sclerosis. The nidus itself may contain areas of calcification. Three-phase skeletal scintigraphy is an option if conventional radiographs are inconclusive.[3] The "double density sign" is characteristic of an osteoid osteoma when evaluating three-phase bone scintigraphy; this is demonstrated as intense focal uptake centrally surrounded by an area of less intense uptake peripherally.[3] Thin-slice CT imaging is considered the imaging modality of choice. CT scans are effective in identifying the anatomic location of the nidus. The characteristic finding on a CT scan is a target-shaped nidus.[8] Bone marrow edema appreciated on MRI can mask the typical features of the tumor, and therefore, MRI is less useful than CT for the evaluation of osteoid osteomas. However, MRI is more accurate than CT in diagnosing cancellous lesions. Hosalkar et al. compared the diagnostic accuracy of MRI versus CT in a prospective study in children. They concluded the correct diagnosis of osteoid osteoma was only 3% with MRI images versus 67% of CT images.[7]

Treatment / Management

Conservative management with NSAIDs is considered a reasonable option in the treatment of osteoid osteomas. Resolution of symptoms from conservative management has been documented to occur at 33 months.[7] However, the negative effects of long term NSAID use prohibit it from being a definitive treatment. Furthermore, recurrence rates following the discontinuation of NSAIDs have no clear documentation in the literature.

Surgical excision is the preferred treatment for an osteoid osteoma. Historically, open en bloc surgical resection with removal of the nidus was considered curative. However, wide block resection of bone in a weight-bearing area has disadvantages including prolonged restriction of physical activity, the potential for pathologic fracture, and requirement of bone grafting with internal fixation.

Less invasive surgical options have been explored to minimize damage to the normal, surrounding bone. Currently, the treatment of choice is CT guided percutaneous radiofrequency ablation.[6] With the guidance of CT, the radiofrequency electrode gets inserted into the nidus, and the nidus is thermally ablated. Documented success with this procedure is as high as 90%.[6]

Differential Diagnosis

The principal differential diagnoses of an osteoid osteoma include chondroblastoma, bone infarction, Brodie’s abscess, stress fracture, chronic osteomyelitis, focal cortical bone abscess, glomus tumor, sclerosing osteitis, solitary enostosis, and an early stage of Ewing's sarcoma.[6][9][10]

Prognosis

An osteoid osteoma has a good prognosis as it is a benign process with no potential for malignant degeneration. If conservative management fails, complete surgical excision is curative.

Complications

If an osteoid osteoma affects the epiphysis, elongation of the limb may occur which can result in a limb length discrepancy. If radiofrequency ablation is performed to treat the benign bone tumor, there are several identified complications, although they are rare. These include cellulitis, thrombophlebitis, nerve damage, skin burns, and reflex sympathetic dystrophy. To reduce the risk of neurovascular damage or damage to the skin, it is recommended radiofrequency ablation be reserved for lesions greater than 1.5 cm from a neurovascular bundle and greater than 1.0 cm from the surface of the skin.[11]

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Historically, wide en bloc excision was performed to treat osteoid osteomas. However, excessive removal of normal surrounding bone resulted in weak bone and prolonged periods of immobilization. With the advent of newer technology and options for surgical excision, the postoperative course has changed significantly. With percutaneous techniques such as radiofrequency ablation, there is minimal damage to the surrounding unaffected tissue which allows immediate weight bearing and the return to daily activities.

Consultations

Timely consultation with an interventional radiologist or foot and ankle specialist is the recommendation for diagnosis and treatment of a patient with symptomatic osteoid osteoma.

Deterrence and Patient Education

An osteoid osteoma is a benign bone-forming tumor that has no potential to become malignant. It classically causes severe pain at night relieved with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications. Occasionally, it resolves without treatment. If it is painful, initial treatment consists of anti-inflammatory medications. The lesion can undergo surgical excision if conservative management fails to provide relief of symptoms.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The diagnosis and treatment of an osteoid osteoma require an interprofessional team of a foot and ankle specialist, pharmacist, radiologist, pathologist, and physical therapist. Once an appropriate history and physical is obtained, the treatment protocol can be established which will determine the level of involvement of the various specialties. A delay in diagnosis may occur due to the vast differential diagnoses and difficulty with diagnostic imaging interpretation. However, a complete history and physical performed by the specialist combined with the imaging interpretation of the radiologist will dictate the treatment protocol.[2] (Level V)

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Ren X, Yang L, Duan XJ. Three-dimensional printing in the surgical treatment of osteoid osteoma of the calcaneus: A case report. The Journal of international medical research. 2017 Feb:45(1):372-380. doi: 10.1177/0300060516686514. Epub 2017 Jan 25 [PubMed PMID: 28222618]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJordan RW, Koç T, Chapman AW, Taylor HP. Osteoid osteoma of the foot and ankle--A systematic review. Foot and ankle surgery : official journal of the European Society of Foot and Ankle Surgeons. 2015 Dec:21(4):228-34. doi: 10.1016/j.fas.2015.04.005. Epub 2015 May 8 [PubMed PMID: 26564722]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKumar R, Chandrashekhar N, Dasan JB, Ashok S, Rastogi S, Gupta V, Hadi M, Choudhury S. Recurrent osteoid osteoma: a case report with imaging features. Clinical imaging. 2003 Jul-Aug:27(4):269-72 [PubMed PMID: 12823924]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGökalp MA, Gözen A, Ünsal SŞ, Önder H, Güner S. An Alternative Surgical Method for Treatment of Osteoid Osteoma. Medical science monitor : international medical journal of experimental and clinical research. 2016 Feb 22:22():580-6 [PubMed PMID: 26898923]

Gurkan V, Erdogan O. Foot and Ankle Osteoid Osteomas. The Journal of foot and ankle surgery : official publication of the American College of Foot and Ankle Surgeons. 2018 Jul-Aug:57(4):826-832. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2017.11.019. Epub 2018 Mar 2 [PubMed PMID: 29503136]

Laurence N, Epelman M, Markowitz RI, Jaimes C, Jaramillo D, Chauvin NA. Osteoid osteomas: a pain in the night diagnosis. Pediatric radiology. 2012 Dec:42(12):1490-501; quiz 1540-2. doi: 10.1007/s00247-012-2495-y. Epub 2012 Oct 23 [PubMed PMID: 23089877]

Atesok KI, Alman BA, Schemitsch EH, Peyser A, Mankin H. Osteoid osteoma and osteoblastoma. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2011 Nov:19(11):678-89 [PubMed PMID: 22052644]

Lewis VO, Morris CD, Parsons TW 3rd. Malignant and benign bone tumors that you are likely to see. Instructional course lectures. 2013:62():535-49 [PubMed PMID: 23395056]

Endo RR, Gama NF, Nakagawa SA, Tyng CJ, Chung WT, Pinto FFE. Osteoid osteoma - radiofrequency ablation treatment guided by computed tomography: a case series. Revista brasileira de ortopedia. 2017 May-Jun:52(3):337-343. doi: 10.1016/j.rboe.2017.04.005. Epub 2017 Apr 28 [PubMed PMID: 28702394]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAtaoglu MB, Ali AK, Ozer M, Topcu HN, Cetinkaya M, Kulduk G. Osteoid Osteoma at the Proximal Diaphysis of the Fifth Metatarsal. Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association. 2017 Jul:107(4):342-346. doi: 10.7547/15-059. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28880602]

Houdek MT, Wenger DE, Sherman CE, Turner NS. Osteoid osteomas of the foot and ankle: a study of patients over a 20-year period. American journal of orthopedics (Belle Mead, N.J.). 2014 Dec:43(12):552-6 [PubMed PMID: 25490009]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence