Introduction

Intercostal nerve blocks are simple to perform and useful for pain management either as the primary intervention or as adjuncts. They are useful for pain in the chest wall and upper abdomen.[1][2]

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

Twelve intercostal nerves supply the sensory innervation for much of the back, trunk, and upper abdomen, as well as the muscular innervation for the intercostal muscles. Each intercostal nerve originates from spinal nerve roots at the same vertebral level as the rib they travel with. As each spinal nerve emerges from the spinal cord, it immediately divides into dorsal and ventral branches. The dorsal nerve branch supplies the motor and sensory innervation of the paravertebral musculature and overlying skin and subcutaneous tissue. The ventral branch continues anterolaterally and becomes the intercostal nerve. Immediately on exiting the intervertebral foramen, the nerve lies between the parietal pleura and the innermost intercostal muscle. Within a few centimeters, the nerve dives between the internal and innermost intercostal muscles, where it remains until it terminates in the anterior chest wall or abdomen.

Each intercostal nerve travels in a neurovascular bundle with an intercostal artery and vein with the nerve running inferior to both blood vessels. This neurovascular bundle accounts for the high levels of local anesthetic uptake into the blood noted after intercostal nerve blocks. The bundle travels inferior to the accompanying rib in the costal groove. Near the midaxillary line, the intercostal nerve sends an offshoot called the lateral cutaneous branch, which travels laterally through the internal and external intercostal muscles where it then divides into a dorsal and ventral branch. Together these innervate the skin and subcutaneous tissue of the lateral trunk and upper abdomen. Just before the individual intercostal nerves terminate, they send another branch called the anterior cutaneous branch, which divides into a lateral and medial branch. These supply the skin and subcutaneous tissue of the anterior trunk and abdomen, including the skin over both the sternum and rectus abdominis.[3]

Indications

Indications include:

Contraindications

The only absolute contraindications are patient refusal for the procedure and active infection over the site of injection. Other relative contraindications are an allergy to local anesthetics, prior nerve injury or damage, inability of the patient to consent to the procedure, anticoagulation, or coagulopathy. Patients should be counseled on the expected results of the intercostal nerve block and pertinent potential complications. Special consideration should also be given if patients have prior nerve injury or neuromuscular disease, which involves the area to be blocked.

Equipment

Equipment includes:

- Skin antiseptic

- Sterile towels

- Sterile gauze

- 50 cm 22 g needle for local anesthetic injection

- 25 g needle for skin wheal

- Local anesthetic

- Sterile gloves

- Ultrasound machine

- Marking pen

- ECG monitor

- Blood pressure monitor

- Pulse oximetry

Generally, a long-acting local anesthetic such as 0.2% ropivacaine or 0.25% bupivacaine is chosen to maximize pain control.[6] Continuous blocks with a nerve catheter can be considered but are rarely used for this particular nerve block. Due to the high degree of local anesthetic uptake from the intercostal space shorter-acting, local anesthetics may be considered, and maximum allowable dosage should be calculated, especially if multiple levels are to be blocked.

Preparation

Providers can perform this block with the patient in the sitting, lateral, or prone position. Provider familiarity and patient comfort should guide positioning. For inexperienced providers, having the patient in the prone position will likely provide the easiest access to the necessary landmarks. Placing a pillow under the upper abdomen or placing the bed in a slight jack-knife can help open the posterior intercostal space. Having the patient dangle their arms over the edge of the bed will retract the scapula laterally, which should help expose the rib angles for the underlying ribs. These maneuvers improve the ability to palpate the landmarks necessary to perform this block safely. After the patient has been properly positioned, it is good practice to mark each level to be blocked as it can be easy to skip a level or perform more than one block on a single level, especially if multiple levels are planned. Palpation of ribs is easiest, approximately 6 cm lateral to the midline, as this should be lateral to the overlying paraspinal musculature. The paraspinal musculature prevents tactile differentiation of rib levels in most healthy patients.

The inferior border of the scapula (which sits over the seventh rib) and the 12th rib are good landmarks to determine the desired intercostal levels. If wishing to provide coverage for abdominal surgery, the fifth to 12th intercostal spaces should be marked. For breast surgery, the second to sixth intercostal spaces should be marked. For thoracic incisions, 1 to 2 levels above and below the planned level should be sufficient. The inferior border of the rib to be blocked should be marked at the angle of the rib to ensure sufficient lateral placement. This can help prevent accidental injection into paravertebral space or inadvertent dural sac puncture. The use of ultrasound can facilitate safe injection closer to the midline if this is necessary.

Technique or Treatment

Successful intercostal nerve block results in the deposition of local anesthetic in the intercostal sulcus outside of the parietal pleura. Correct placement will result in ipsilateral numbness of the individual intercostal levels that have been blocked. It is rare for the blockade to extend to superior or inferior levels unless a large amount of local anesthetic is injected or the needle placed too close to the midline resulting in spread to the paravertebral space. Usually, the block level is determined by the number of blocks performed and is limited to the dermatome of the intercostal nerves which have been targeted.

Anatomic Landmark

After cleansing the skin with an antiseptic, a skin wheal should be performed with 1 to 2 mL of local anesthetic. The fingers of the palpating hand should be used to pull the skin up so that the needle will contact the middle of the rib to be blocked. Generally, a 22-gauge 50-mm long needle is sufficient to perform the block. As the skin is fixed with the palpating hand, the needle is placed through the skin wheal at an approximately 20-degree angle cephalad until it makes contact with the rib, which should be made within 1cm. The palpating hand then allows the skin to return to its normal position as the needle is “walked-off,” the inferior border of the rib. As the needle walks off the inferior edge, it should be advanced another 1 to 3 mm anteriorly, where a subtle “pop” may be appreciated as the needle advances through the fascia of the internal intercostal muscle. After negative aspiration, 3 to 5 mL of local anesthetic can be injected.[3]

Ultrasound-Guided

Ultrasound guidance may decrease the chance of intravascular injection, pneumothorax, and allows injection closer to the midline than anatomic landmarks. This increases the chance that injection is made before the division of the lateral branch, which is necessary to achieve anesthesia of the entire intercostal dermatome.

The individual ribs to be blocked should be marked out as with the landmark technique. The ultrasound probe is then placed in a sagittal plane about 4 cm lateral to the spinous process. The ribs are visualized as a shadow while the pleura and lung are visualized anterior to the intercostal space. The needle can then be inserted in or out of a plane to the transducer and advanced until the tip is just below the inferior border of the rib. After negative aspiration, 3 to 5 mL of local anesthetic is injected, and the pleura should be visualized being pushed away.[3]

Complications

Care should be taken to perform this block under sterile technique to avoid infection. History of coagulopathy or anticoagulation should be discussed to reduce the risk of bleeding. Performing this block awake can alert the provider to pneumothorax or intraneural injection symptoms, which may go unnoticed in a sedated or anesthetized patient. Pneumothorax is rare and usually only requires monitored observation, although providers should be ready to perform needle decompression or insert a chest tube if necessary. Local anesthetic systemic toxicity is, fortunately, also a rare event. However, local anesthetic uptake from this region is high, and providers should recognize LAST and provide appropriate treatment.

The use of dilute concentrations of local anesthetic and keeping total dose below the maximum allowable will decrease systemic toxicity risk. Several case reports of inadvertent spinal after intercostal nerve block have been described.[7] This is thought to be secondary to local anesthetic spreading medially through the dura or to the rare occurrence of injection into a dural sac, which has been described protruding laterally from the vertebral foramen. Aspiration before injection to rule out intravascular, intrapleural, or intrathecal injection should be performed to exclude these complications, but negative aspiration is not guaranteed. Patients should be monitored for 20 to 30 minutes after the block has been performed to exclude these complications.

Clinical Significance

Intercostal nerve blocks provide a reliable unilateral dermatomal band of analgesia for the vertebral level at which they are performed. They have been shown to reliably improve respiratory function in patients with chest wall pain making them useful for recovery after thoracic surgery. They are technically easier to perform than a paravertebral nerve block or epidural but risk increased vascular uptake of local anesthetic and systemic toxicity as well as pneumothorax. A potential disadvantage compared to paravertebral nerve block or thoracic epidural is the necessity for several blocks to be performed if more than one level or bilateral coverage is required. They do not provide complete surgical analgesia for thoracic surgery, so they must be part of a multi-modal plan if they are to be used for intraoperative analgesia.[8]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

An intercostal nerve block is commonly performed by the nurse anesthetist, anesthesiologist, emergency department physician, thoracic surgeon, a trauma surgeon, and the pain specialist. While the performance of an intercostal nerve block is relatively simple, the key is to avoid complications like pneumothorax or inadvertent injection into an artery. Any healthcare professional performing an intercostal nerve block must know how to deal with the complications and have resuscitative equipment in the room.

Media

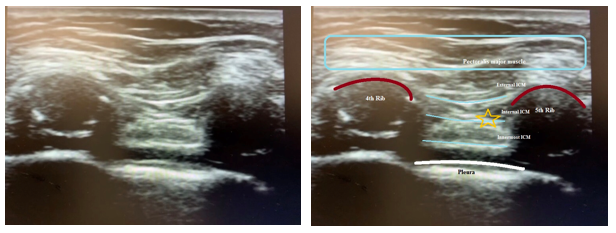

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Figure 1.- Sonogram showing the correct place where local anesthetic should be administered (yellow star), between the innermost intercostal muscle and internal intercostal muscle, while performing an intercostal nerve block. It also shows where the parietal pleura is located. Contributed by Rosa Lopez-Rincon, MD

References

Painless abdominoplasty: the efficacy of combined intercostal and pararectus blocks in reducing postoperative pain and recovery time., Feng LJ,, Plastic and reconstructive surgery, 2010 Nov [PubMed PMID: 21042130]

Management of acute postoperative pain with continuous intercostal nerve block after single port video-assisted thoracoscopic anatomic resection., Hsieh MJ,Wang KC,Liu HP,Gonzalez-Rivas D,Wu CY,Liu YH,Wu YC,Chao YK,Wu CF,, Journal of thoracic disease, 2016 Dec [PubMed PMID: 28149550]

Comparison of anatomic landmarks and ultrasound guidance for intercostal nerve injections in cadavers., Bhatia A,Gofeld M,Ganapathy S,Hanlon J,Johnson M,, Regional anesthesia and pain medicine, 2013 Nov-Dec [PubMed PMID: 24121611]

Effectiveness of intercostal nerve block for management of pain in rib fracture patients., Hwang EG,Lee Y,, Journal of exercise rehabilitation, 2014 Aug [PubMed PMID: 25210700]

The efficacy of ilioinguinal-iliohypogastric and intercostal nerve co-blockade for postoperative pain relief in kidney recipients., Shoeibi G,Babakhani B,Mohammadi SS,, Anesthesia and analgesia, 2009 Jan [PubMed PMID: 19095869]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAlleviating Thoracotomy Pain With Intercostal Liposomal Bupivacaine: A Case Report., Saby A,Swaminathan K,Pangarkar S,Tribuzio B,, PM & R : the journal of injury, function, and rehabilitation, 2016 Nov [PubMed PMID: 27292436]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceInadvertent total spinal anesthesia after intercostal nerve block placement during lung resection., Chaudhri BB,Macfie A,Kirk AJ,, The Annals of thoracic surgery, 2009 Jul [PubMed PMID: 19559248]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceContinuous intercostal versus paravertebral blockade for multiple fractured ribs., Gadsden J,Kwofie K,Shastri U,, The journal of trauma and acute care surgery, 2012 Jul [PubMed PMID: 22743402]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence