Introduction

The neck is the bridge between the head and the rest of the body. It is located in between the mandible and the clavicle, connecting the head directly to the torso, and contains numerous vital structures. It contains some of the most complex and intricate anatomy in the body and is comprised of numerous organs and tissues with essential structure and function for normal physiology. Structures contained within the neck are responsible for breathing, speaking, swallowing, regulation of metabolism, support and connection of the brain and cervical spine, and circulatory and lymphatic inflow and outflow from the head.[1]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

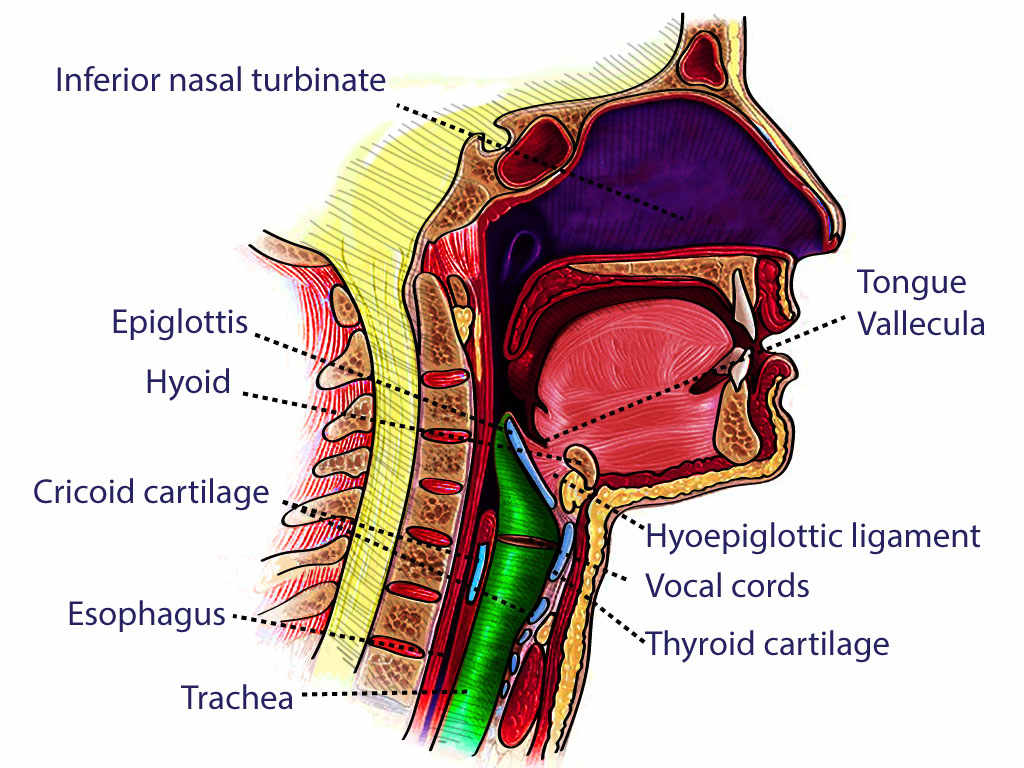

The neck can be envisioned very simply as a pathway (or connection) between the head and the rest of the body. It is home to the proximal esophagus, trachea, thyroid gland, and the parathyroid glands. It provides conduits for blood flow to the brain and head, supports the head and moves it accordingly, and transmits nervous signals from the brain to the rest of the body. It is an intricate part of the body with many different planes and compartments.

The neck separates into two triangles: anterior and posterior, with these divided into additional triangles and anatomic areas. The anterior triangle is surrounded inferiorly by the sternal notch and clavicle, laterally by the sternocleidomastoid, and medially by the trachea, thyroid, and cricoid cartilages.[2] The posterior triangle is bordered posteriorly by the trapezius muscle, anteriorly by the sternocleidomastoid muscle, and inferiorly by the clavicle.[3]

The anterior triangle is subdivided into four smaller segments (also triangles): the submental, submandibular, carotid, and muscular triangles.

- The submental triangle, also called the suprahyoid triangle, contains the mylohyoid muscle as its floor. Inferiorly, its border is the hyoid bone. Medially, its border is the midline of the neck. Posteriorly, the border is the anterior belly of the digastric.[1]

- The submandibular triangle, or the submaxillary triangle, is superiorly bordered by the mandible. The other portions of the triangle are the anterior and posterior bellies of the digastric muscle.[1]

- The carotid triangle, or the superior carotid triangle, is bordered posteriorly by the sternocleidomastoid muscle, anteriorly by the omohyoid muscle, and superiorly by the stylohyoid muscle and posterior belly of the digastric. The thyrohyoid, hyoglossus, middle pharyngeal constrictor, and inferior pharyngeal constrictor muscles form the floor of the carotid triangle.[1]

- The muscular triangle, or the inferior carotid triangle, is bordered medially by the midline of the neck, superiorly by the superior belly of the omohyoid, and posteriorly by the sternocleidomastoid.[1]

The posterior triangle is divided into the occipital triangle and subclavian triangle by the inferior belly of the omohyoid muscle.[1]

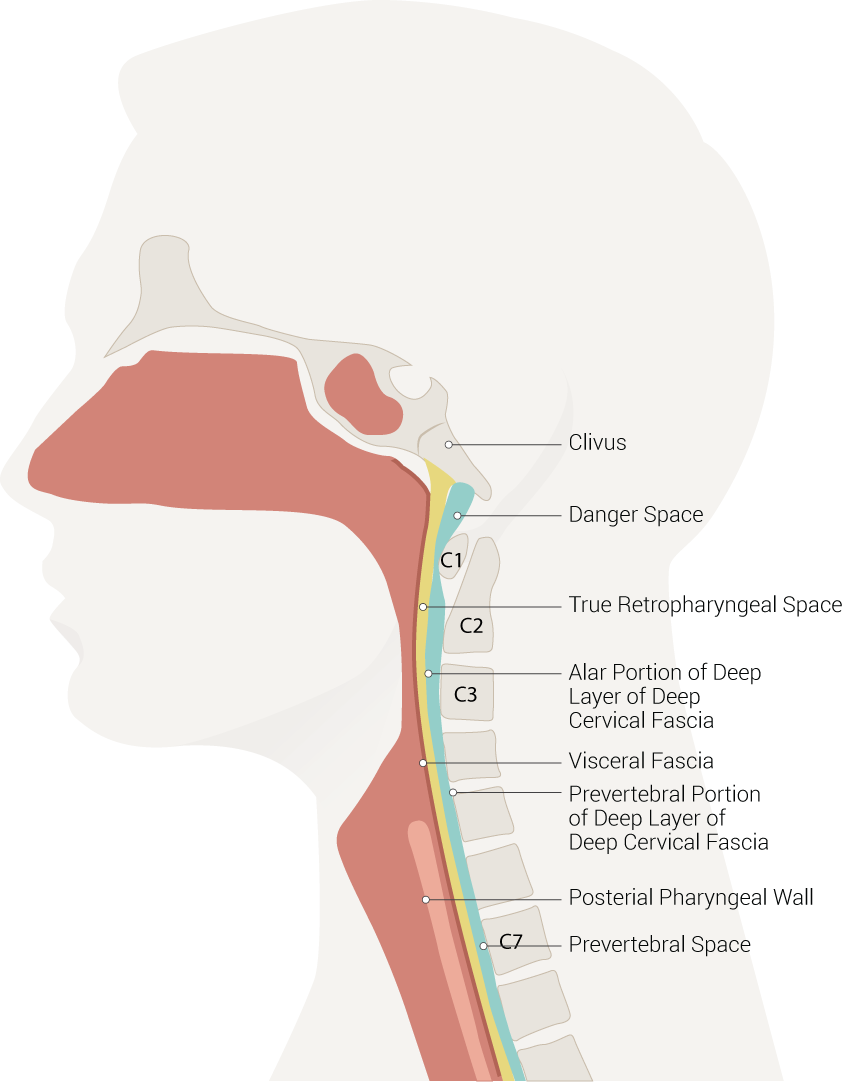

The neck also has several layers of fascia, but the two main divisions are superficial and deep fascia.

The superficial cervical fascia extends from the head down to the thorax and axillae. In the neck, it contains the superficial lymph nodes, cutaneous nerves, external and anterior jugular veins, and the platysma muscle. It is arranged loosely to allow for neck movement.[1][4]

The deep cervical fascia subdivides into the superficial layer of deep cervical fascia, the middle layer of deep cervical fascia, and the deep layer of deep cervical fascia.[5]

- The superficial layer of deep cervical fascia, or investing layer, lies between the muscles of the neck and the superficial cervical fascia, encircling the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles. It attaches inferiorly to the scapula, clavicle, and manubrium. Superiorly, it attaches to the mandible, mastoid process, superior nuchal line, and external occipital protuberance.[5]

- The middle layer of deep cervical fascia, or the pretracheal layer, runs from the mediastinum inferiorly to the skull base superiorly. It has a muscular and visceral division. The muscular division encloses the strap muscles, sternohyoid, sternothyroid, omohyoid, and thyrohyoid muscles. The visceral division encloses the larynx, pharynx, esophagus, thyroid, parathyroid glands, trachea, and recurrent laryngeal nerve.[5]

- The deep layer of deep cervical fascia, or prevertebral layer, runs from the skull base to the mediastinum. Its two divisions are the alar and prevertebral layers. These layers surround the deep muscles of the neck and the cervical vertebrae, forming part of the retropharyngeal space.[5]

Embryology

Many important neurovascular and musculoskeletal structures in the neck embryologically derive from the pharyngeal arches, which are outgrowths on the lateral sides of the head of the embryo. There are six pharyngeal arches, but the fifth one disappears almost immediately after it forms. Each pharyngeal arch gets separated by an ectodermal pharyngeal groove and an endodermal pharyngeal pouch. Each arch contains endoderm, mesoderm, ectoderm, and neural crest cells.[6]

-

Pharyngeal arch 1 develops into the anterior belly of the digastric muscle, mylohyoid muscle, mandible, and mylohyoid branch of the trigeminal nerve.

-

Pharyngeal arch 2 develops into the cervical branch of the facial nerve, posterior belly of the digastric muscle, platysma muscle, stylohyoid muscle, and the lesser horn of the hyoid bone.

-

Pharyngeal arch 3 develops into the greater horn of the hyoid, stylopharyngeus muscle, glossopharyngeal nerve, common carotid artery, and the proximal section of the internal carotid artery.

-

Pharyngeal arch 4 develops into the thyroid cartilage, pharyngeal constrictor muscles, cricothyroid muscle, levator veli palatine muscle, and the superior laryngeal nerve.

-

Pharyngeal arch 6 develops into the cricoid cartilage, intrinsic muscles of the larynx, and the recurrent laryngeal nerve.

- Pharyngeal pouch 3 develops into the inferior parathyroids, while pharyngeal pouch 4 develops into the superior parathyroids and the ultimobranchial body. The ultimobranchial body eventually becomes the parafollicular cells of the thyroid.

The pharyngeal arches, pouches, and grooves develop into other structures in the head as well but they are beyond the scope of this article. Please see the relevant articles in StatPearls.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

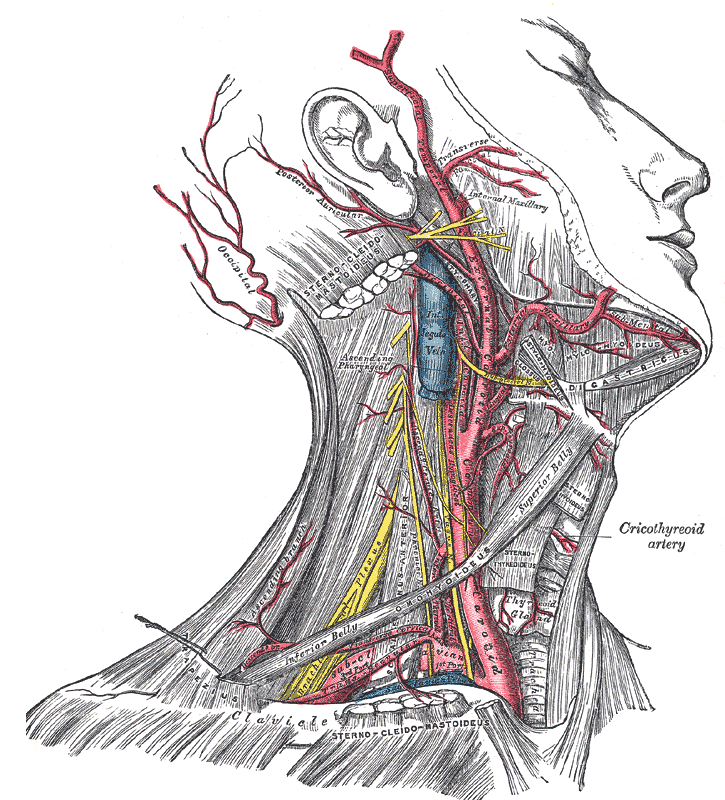

The major blood vessels of the neck are confined within the carotid sheath. These are the common carotid artery, the internal carotid artery, and the internal jugular vein.

The right common carotid artery originates from the brachiocephalic artery, while the left common carotid artery originates directly from the aortic arch. The common carotid bifurcates into the internal carotid and external carotid arteries at the level of the superior portion of the thyroid cartilage. The external carotid artery exits the carotid sheath and supplies the superficial aspect of the face and parts of the neck. It gives off the superior thyroid artery, lingual artery, facial artery, and occipital artery. The internal carotid artery continues into the temporal bone through the carotid canal and joins the circle of Willis to supply the ophthalmic artery, anterior cerebral artery, and the middle cerebral artery.[1][7]

The internal jugular vein is continuous with the sigmoid sinus and exits the skull via the jugular foramen. It descends within the carotid sheath and receives drainage from the facial, lingual, and superior and middle thyroid veins. It eventually anastomoses with the subclavian vein to form the brachiocephalic vein.[7]

Blood from the face and scalp drains into the external jugular vein, which travels down the sternocleidomastoid border and drains into the subclavian vein. The anterior jugular veins also anastomose with the external jugular vein, with anastomotic variances discussed in other StatPearls article topics for each vein.[1]

Many lymph nodes exist in the neck, with the majority located along the course of the internal jugular vein. The lateral neck lymph nodes exist in anterior and posterior chains on each side of the neck, lateral to and closely associated with the internal jugular veins. These drain the vast majority of structures in the head and neck. The deep central neck is drained by lymph node chains contiguous with the mediastinal lymph nodes, responsible for draining the thyroid and peri-thyroid area and cervical trachea. There is also a retropharyngeal nodal plexus that drains the nasopharynx and skull base. The supraclavicular lymph nodes are located just above the clavicle. Virchow's node, a left suprascapular lymph node, lies near the junction of the thoracic duct and the left subclavian vein, where the lymph from most of the body drains into the systemic circulation. Therefore, tumor embolization from abdominal (gastric cancer) and pelvic regions (ovarian cancer) may cause enlargement of Virchow's node (sentinel node).

Nerves

The neck is home to a multitude of nervous system structures.

The cervical ganglia are a trio of sympathetic nervous system ganglia that lie alongside the vertebral column. The superior cervical ganglion lies at the C2/C3 intervertebral level, while the middle cervical ganglion lies at the C6/C7 intervertebral level. The inferior cervical ganglion is fused with the first thoracic ganglion to create the stellate ganglion at the C7/T1 intervertebral level.[8]

The brachial plexus forms from the anterior rami of the C5-T1 spinal projections and divides into roots, trunks, divisions, cords, and branches, in that order from proximal to distal. After the roots exit the interscalene triangle between the anterior and middle scalene muscles, they form trunks at the level of the subclavian artery. The C5 and C6 roots form the upper trunk, while the C8 and T1 roots form the lower trunk. The C7 root forms the middle trunk. As these trunks cross the clavicle and exit the neck region, they separate into anterior and posterior divisions.[8]

The anterior rami of the C1-C4 vertebrae constitute the cervical plexus. These are located posterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle and anterior to the middle scalene muscle, supplying both muscular and sensory innervation. They provide sensory innervation to the neck, clavicle, and skin surrounding the ear. The muscular branches innervate the infrahyoid muscles, excluding the thyrohyoid muscle, as well as the diaphragm through the phrenic nerve. The phrenic nerve arises mostly from the C4 ventral rami, with smaller contributions from the C3 and C5 rami, hence the mnemonic "C3, 4, and 5 keep the diaphragm alive." The phrenic nerve serves to contract the diaphragm, a muscle of breathing that lies between the abdomen and thorax.[8]

Ansa cervicalis, a part of the cervical plexus, is embedded in the carotid sheath anterior to the internal jugular vein, in the carotid triangle. It consists of superior and inferior roots. The superior root is formed by C1 nerve fibers of the cervical plexus, which travel in the cranial nerve XII and then separates in the carotid triangle to make the superior root. The superior root eventually goes around the occipital artery and then falls on the carotid sheath. The inferior root consists of fibers from spinal nerves C2 and C3. It gives off branches to the inferior belly of the omohyoid muscle, and the lower parts of the sternothyroid and sternohyoid muscles. The paralysis of ansa cervicalis may lead to the change in the quality of voice, probably due to loss of support of infrahyoid muscles to the larynx.

Multiple cranial nerves also run through the neck into various parts of the body. Cranial nerve X, or the vagus nerve, leaves the skull through the jugular foramen, moves downward in the carotid space, and then enters the thorax.[9] In the neck, the vagus nerve gives off the recurrent laryngeal, superior laryngeal, meningeal, pharyngeal, carotid body, and auricular nerves.[8]

Importantly, the superior laryngeal nerve travels down the side of the pharynx, medial to the carotid sheath. It divides into two branches: the external branch and the internal branch. The external branch travels with the superior thyroid artery and provides motor innervation to the cricothyroid muscle. The internal branch pierces the thyrohyoid membrane along with the superior laryngeal artery, receiving sensory input from the supraglottic larynx and hypopharynx.[8]

The recurrent laryngeal nerve loops underneath the right subclavian artery, but loops under the left aortic arch in the thorax proper. It then travels upward, posterior to the thyroid lobes, and enters the larynx by traveling through the thyrohyoid membrane.[8] While the superior laryngeal nerve innervates the cricothyroid muscle (responsible for vocal fold adDuction), the recurrent laryngeal nerve innervates all of the laryngeal muscles responsible for vocal fold abduction.[10]

Cranial nerve XI (spinal accessory nerve) has a cranial root and a spinal root. The cranial root exits the jugular foramen and joins the vagus nerve. It crosses the posterior cervical triangle at the posterior digastric muscle and continues inferiorly until it innervates the sternocleidomastoid muscle. It then continues superficially to the levator scapulae muscle and ends in the trapezius.[8]

Muscles

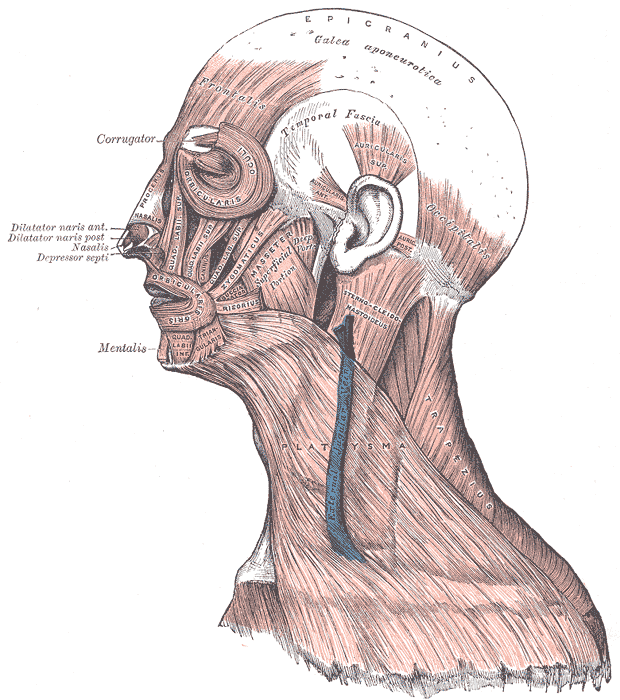

The platysma is a thin muscle that extends from the upper thorax to the cheek and lower lip. It functions to draw the central lip inferiorly (the commissure of the lip is contracted inferiorly via the depressor anguli oris, innervated by the marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve), and tense the neck superficially, and receives nerve supply from the cervical branch of the facial nerve.[11]

The sternocleidomastoid muscle has two muscle heads that originate from the sternal manubrium and the medial clavicle. These muscle heads merge and insert at the mastoid process of the temporal bone and the superior nuchal line. It functions to rotate the head to the opposite side that is contracting. Its innervation is by CN XI.[12]

The trapezius muscle is a large muscle of the back that extends from the external protuberance of the occipital bone inferiorly to the lower thoracic vertebrae and laterally to the spine of the scapula. CN XI innervates the trapezius, and functions to stabilize and move the scapula.[13]

The suprahyoid muscles consist of the digastric, mylohyoid, and geniohyoid muscles. These muscles attach to the hyoid bone and portions of the mandible, except for the digastric muscle. The digastric muscle has two bellies, the posterior belly of which attaches to the mastoid process of the temporal bone. Innervation of the geniohyoid is via CN XII, also known as the hypoglossal nerve. The anterior belly of the digastric muscles and the mylohyoid receive nerve supply from the mylohyoid nerve, a tributary of the mandibular division of CN V. The facial nerve innervates the digastric muscle's posterior belly. Their function is to elevate the hyoid bone.[1]

The infrahyoid muscles consist of the thyrohyoid, omohyoid, sternothyroid, and sternohyoid muscles. They all obtain their nerve supply via the ansa cervicalis (C1-C3) except for the thyrohyoid muscle, which is innervated by CN XII. The omohyoid muscle originates at the scapula, passes around the sternocleidomastoid, and attaches to the hyoid bone. The names of the sternohyoid, sternothyroid, and thyrohyoid muscles describe their origin and insertion sites.[1]

Physiologic Variants

The external carotid artery usually gives off three anterior branches. From inferior to superior, they are the superior thyroid artery, the lingual artery, and the facial artery.

The superior thyroid artery travels inferiorly to the thyroid gland and gives off the sternomastoid artery. Occasionally, the sternomastoid artery will arise directly from the external carotid artery.[14]

The facial artery normally exits the external carotid artery above the greater horn of the hyoid and travels superiorly behind the submandibular gland. Once it reaches the stylohyoid muscle, it turns medially and courses towards the angle of the mouth and medial canthus. In 10% of people, the facial artery is hypoplastic and does not travel to the angle of the mouth. In 1% of people, it fails to reach the face completely.[14]

Surgical Considerations

During many shoulder surgeries, nerve blocks are used to decrease pain during the first 24 hours of surgery, which improves patient satisfaction, and decreases the need for opioid pain relief. These nerve blocks are often conducted under ultrasound guidance and are delivered onto the brachial plexus immediately as they exit the anterior and middle scalene muscles in the neck. There are many more cervical blocks utilized in surgery, discussed elsewhere in specific articles in StatPearls.[15]

Most spinal accessory nerve damage occurs via iatrogenic causes including neck dissection surgery or excisional biopsies of cervical lymph nodes, due to its close location to the cervical lymphatics; this will result in loss of function to the trapezius muscle and the sternocleidomastoid muscle.[16][17]

It is also important to consider the location of the superior laryngeal nerve and the recurrent laryngeal nerve during surgery on the neck, especially of the thyroid, where both nerves must be identified and preserved. Injuring the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve would cause paralysis of the cricothyroid muscle, resulting in an alteration in sound pitch, or dysphonia. If the recurrent laryngeal nerve suffers damage, the result would be paralysis of the intrinsic laryngeal muscles, except for the cricothyroid muscle, causing vocal cord paralysis.[18]

Clinical Significance

Damage to the cervical sympathetic ganglion can cause Horner's syndrome, which is ipsilateral ptosis, miosis, and facial anhidrosis. Damage to these structures can also lead to First Bite Syndrome, where the first bite of food is painful owing to autonomic dysfunction due to trauma in the deep parotid space and/or superior cervical ganglion.[4][19]

Any time there is neck trauma, one needs to be concerned about the viability of the phrenic nerve. If the C3, C4, or C5 ventral rami are damaged, this could interfere with the diaphragm working correctly.

Torticollis occurs when the sternocleidomastoid muscle shortens or contracts irregularly, causing a twisting of the neck opposite to the side of the abnormal muscle. This condition can occur during birth if the SCM is damaged, leading to fibrosis and shortening of the muscle fibers. It can also occur due to increased muscle tone, or dystonia, resulting from emotional stress or sudden movements.[20]

During trauma evaluation, it is imperative to rule out any carotid dissection in the neck. Sometimes patients present with miosis, neck pain, and neurological deficits based on the involvement of the dissection. Early diagnosis permits the treatment of a major stroke and avoids eventual disability.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Neck Spaces Pertinent to Retropharyngeal Abscess. The illustration of neck spaces shows the danger space, clivus, true retropharyngeal space, an alar portion of the deep layer of deep cervical fascia, visceral fascia, a prevertebral portion of the deep layer of deep cervical fascia, posterior pharyngeal wall, and prevertebral space.

Contributed by B Palmer

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Muscles of the Head, Face, and Neck. The epicranius, galea aponeurotica, frontalis, temporal fascia, auricularis superior, auricularis anterior, auricularis posterior, occipitalis, sternocleidomastoid, platysma, trapezius, orbicularis oculi, corrugator, procerus, nasalis, dilator naris anterior, dilator naris posterior, depressor septi, mentalis, orbicularis oris, masseter, zygomaticus, and risorius muscles are shown in the image.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

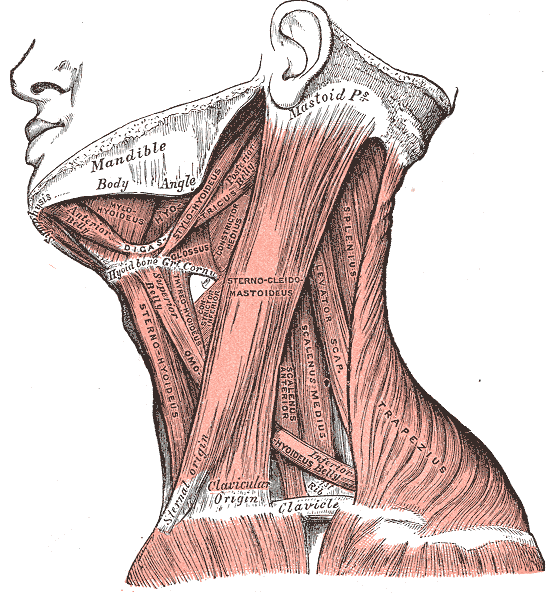

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Neck Muscles. This lateral-view illustration shows the trapezius, sternocleidomastoideus, sternohyoideus, omohyoideus belly, scalenus anterior and medius, levator scapulae, splenius, mylohyoideus, thyrohyoideus, digastricus, and stylohyoideus muscles. The mandible, mastoid process, clavicle, and hyoid bone are also shown.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Kohan EJ, Wirth GA. Anatomy of the neck. Clinics in plastic surgery. 2014 Jan:41(1):1-6. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2013.09.016. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24295343]

Shadfar S, Perkins SW. Anatomy and physiology of the aging neck. Facial plastic surgery clinics of North America. 2014 May:22(2):161-70. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2014.01.009. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24745379]

Ihnatsenka B, Boezaart AP. Applied sonoanatomy of the posterior triangle of the neck. International journal of shoulder surgery. 2010 Jul:4(3):63-74. doi: 10.4103/0973-6042.76963. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21472066]

Guidera AK, Dawes PJ, Fong A, Stringer MD. Head and neck fascia and compartments: no space for spaces. Head & neck. 2014 Jul:36(7):1058-68. doi: 10.1002/hed.23442. Epub 2014 Jan 29 [PubMed PMID: 23913739]

Warshafsky D, Goldenberg D, Kanekar SG. Imaging anatomy of deep neck spaces. Otolaryngologic clinics of North America. 2012 Dec:45(6):1203-21. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2012.08.001. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23153745]

Frisdal A, Trainor PA. Development and evolution of the pharyngeal apparatus. Wiley interdisciplinary reviews. Developmental biology. 2014 Nov-Dec:3(6):403-18. doi: 10.1002/wdev.147. Epub 2014 Aug 29 [PubMed PMID: 25176500]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGarner DH, Kortz MW, Baker S. Anatomy, Head and Neck: Carotid Sheath. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30137861]

Lee JH, Cheng KL, Choi YJ, Baek JH. High-resolution Imaging of Neural Anatomy and Pathology of the Neck. Korean journal of radiology. 2017 Jan-Feb:18(1):180-193. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2017.18.1.180. Epub 2017 Jan 5 [PubMed PMID: 28096728]

Ha EJ, Baek JH, Lee JH, Kim JK, Shong YK. Clinical significance of vagus nerve variation in radiofrequency ablation of thyroid nodules. European radiology. 2011 Oct:21(10):2151-7. doi: 10.1007/s00330-011-2167-6. Epub 2011 Jun 2 [PubMed PMID: 21633824]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMasuoka H, Miyauchi A, Yabuta T, Fukushima M, Miya A. Innervation of the cricothyroid muscle by the recurrent laryngeal nerve. Head & neck. 2016 Apr:38 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):E441-5. doi: 10.1002/hed.24015. Epub 2015 Jul 14 [PubMed PMID: 25581356]

Hwang K, Kim JY, Lim JH. Anatomy of the Platysma Muscle. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2017 Mar:28(2):539-542. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000003318. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28027174]

Bordoni B, Jozsa F, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Head and Neck, Sternocleidomastoid Muscle. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30422476]

Ourieff J, Scheckel B, Agarwal A. Anatomy, Back, Trapezius. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30085536]

Tan BK, Wong CH, Chen HC. Anatomic variations in head and neck reconstruction. Seminars in plastic surgery. 2010 May:24(2):155-70. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1255333. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22550436]

Falyar CR, Shaffer KM, Perera RA. Localization of the brachial plexus: Sonography versus anatomic landmarks. Journal of clinical ultrasound : JCU. 2016 Sep:44(7):411-5. doi: 10.1002/jcu.22354. Epub 2016 Mar 29 [PubMed PMID: 27028598]

Cappiello J, Piazza C, Nicolai P. The spinal accessory nerve in head and neck surgery. Current opinion in otolaryngology & head and neck surgery. 2007 Apr:15(2):107-11 [PubMed PMID: 17413412]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKim DH, Cho YJ, Tiel RL, Kline DG. Surgical outcomes of 111 spinal accessory nerve injuries. Neurosurgery. 2003 Nov:53(5):1106-12; discussion 1102-3 [PubMed PMID: 14580277]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAllen E, Minutello K, Murcek BW. Anatomy, Head and Neck, Larynx Recurrent Laryngeal Nerve. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29261997]

Chiba M, Hirotani H, Takahashi T. Clinical Features of Idiopathic Parotid Pain Triggered by the First Bite in Japanese Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Case Study of Nine Patients. Pain research and treatment. 2018:2018():7861451. doi: 10.1155/2018/7861451. Epub 2018 Mar 29 [PubMed PMID: 29796314]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCunha B, Tadi P, Bragg BN. Torticollis. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30969679]