Introduction

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC), previously known as lymphoepithelioma, is an undifferentiated form of squamous cell carcinoma arising from the epithelium of the nasopharynx (see Image. Nasopharyngeal Mass). It is the most common malignancy of the nasopharynx. Endemic to parts of Asia and Africa but found worldwide, the malignancy shows a variable rate of occurrence ranging from high incidence in the southern part of China (25 to 50 cases per 100,000) to a low rate in European populations (1 case per 100,000).[1] A complex interplay of genetic susceptibility and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection is responsible for these epidemiological patterns. There is a male predominance.[2]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

An interplay of environmental factors, genetic structure, and EBV infection is involved in the etiology of the disease. Environmental factors, including smoking (2 to 6-fold increased risk), heavy alcohol consumption, and nitrosamine-containing food agents, have been considered to have an involvement.[3] Secondly, the genetic structure of the demographics involved also plays a vital role, as explained by the overwhelming incidence in the Chinese population (representing up to 18% of all cancers in parts of southern China and Taiwan).[1] Lastly, EBV infection, coupled with genetic susceptibility, has shown a substantial relevance to the disease.[4][5]

Epidemiology

NPC is endemic to southern China, Southeast Asia, and Africa. The rate varies from a minuscule value of less than 1 per 100,000 individuals in non-endemic areas to a high of 25 to 50 cases per 100,000 males and 15 to 20 cases per 100,000 individuals in females in endemic regions.[6]

Histopathology

Histopathological evaluation can elucidate which category the tumor falls in.[7] On histopathological grounds, NPC can fall into 3 main sub-groups as per WHO classification:

- Keratinizing type (20% to 25%)

- Non-keratinizing differentiated type (10% to 15%)

- Non-keratinizing undifferentiated (60% to 65%)

History and Physical

Patients can have variable presentations depending on the area of disease involvement. The most common site of origin is the lateral aspect of the nasopharynx and the fossa of Rosenmuller.

- Nasal symptoms: A subset of patients present with nasal symptoms, including nasal obstruction, epistaxis, post-nasal drip, hyponasal speech, or cacosmia. Symptomatology is proportionate to the size of growth and the extent of local involvement—around 80% of the individuals suffering from the disease present with nasal symptoms.

- Otological symptoms: Patients may present with symptoms secondary to the tumor obstructing the Eustachian tube, such as conductive hearing loss, middle ear effusion, or aural fullness. An adult with unilateral middle ear effusion requires visualization of the nasopharynx to exclude neoplasm. Half of the patients with NPC have some form of otological complaint during the disease caused by the growing mass obstructing the outflow of the Eustachian tube.

- Neurological symptoms: Intracranial extension is prevalent among 8% to 12% of patients — various forms of cranial nerve involvement present with the associated symptom. Cranial nerve palsy is found in 20% of NPC patients and may be the presenting symptom[8]. The most commonly involved nerve is the abducens nerve.[9]

- Nodal involvement: An enlarged cervical lymph node is 1 of the most common presenting features. Lymph nodes of the apex of the posterior triangle and the upper jugular are initially most commonly involved, together with retropharyngeal nodes. Supraclavicular nodes are the last to be involved and are a sign of advanced disease.[10]

Distant metastasis and paraneoplastic syndrome: Symptoms associated with distant spread rarely present to the primary caregiver. The most significant spread includes the liver and lungs. It is sometimes difficult to assess the primary site of malignancy when metastatic pulmonary lesions occur. PET scan aids in the differentiation of the 2 (see Image. PET Scan). Secondly, a handful of cases present with symptoms of dermatomyositis. The progression of the disease might initiate with the malignant lesion or can present after the initial diagnosis of NPC.[11]

Evaluation

Lab Investigations

- Baseline investigations may include complete blood count, and renal and liver function tests can be obtained if there is a concern for metastasis or paraneoplastic syndrome.

- EBV serum IgA levels may carry diagnostic and prognostic significance, particularly in endemic populations.[11]

Imaging Studies

- Computed tomography: CT scan with IV contrast is the modality of choice for assessing bone invasion and the extent of some soft tissues, as well as cervical nodal basins (see Video. Radiologic Imaging Study, Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma).

- Magnetic resonance imaging: MRI is the superior modality for assessing intracranial extension, cranial nerve involvement, and defining paranasal sinus involvement. MRI also provides excellent soft-tissue detail when assessing muscle involvement. There is also no radiation exposure with MRI as compared to CT.

- PET scan is the modality of choice for assessing remission and investigating recurrence. It is also routinely employed at initial staging to identify distant metastases.

Endoscopic Evaluation and Histopathological Analysis

- The nasopharynx is readily accessible for biopsy via endoscopic, trans-nasal routes. If cervical metastases are easily palpable or visualized under ultrasound or CT guidance, they can also be biopsied via fine-needle aspiration.

Treatment / Management

The mainstay of treatment for NPC is radiotherapy, with the addition of chemotherapy for advanced-stage disease. Surgical intervention is limited to extremely small primary lesions or small recurrences, as the morbidity of large-scale surgical resection is often significantly more than the morbidity associated with radiotherapy to the region.

Radiotherapy

Radiation therapy is the management of choice for primary lesions and cervical metastases. NPC often metastasizes early to the cervical lymph nodes, and this is frequently a presenting complaint. The tumor also grows locally, involving the paranasopharyngeal spaces and musculature, and may do so with little to no symptoms present. Consequently, a dose of approximately 65 Gy for primary tumors with 50 to 55 Gy is also necessary for node-negative necks. A recent innovation in the delivery system employed for radiation is intensity modulation or intensity-modulated radiotherapy. The system comes equipped with a CT, taking slices of the area involved. The physician specifies the beam's targeted area and modulates the beam's intensity.[12]

Brachytherapy is another innovative technique for targeted radiotherapy. It involves implanting gold grains or iridium implants jacketed for localized radiotherapy via a split incision of the soft palate. This technique is infrequently used in the modern era of intensity-modulated radiotherapy. Radiotherapy is also employed for recurrent NPC. However, repeat radiation to the same area with curative intent depends on the time elapsed since initial treatment and may fall into clinical trials. Radiation therapy can be used for palliative intent as well.[5][13]

Chemotherapy

In locally advanced regional diseases, concomitant chemoradiotherapy is the mainstay of management, either via induction or concurrent therapy protocols. The most frequently used initial agent is cisplatin, and the standard of care is a dose of 100 mg every third week. Chemotherapy is also the option of choice when distant metastasis is involved. NPC with distant poly-metastasis is offered palliative chemotherapy. The agents of choice are cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil. With recent advances, several chemotherapeutic agents are available to continue therapy. However, the median survival rate is not more than a year.[5][13]

Surgical Intervention

Surgical intervention is employed primarily as a salvage option. The nasopharynx is a small and deep area that is hard to access, thus making the surgical approach sometimes difficult and inappropriate. However, when encountering locally recurring diseases, patients should be given the option of surgical intervention.[14][15] Nasopharyngectomies can be carried out using several approaches, and the approach chosen should be tailored to the surgeon's expertise and the patient's general condition. The following are some of the popular approaches to the cavity.

- Inferior approach- via transpalatal incision

- Lateral approach- via the lateral skull base

- Inferolateral approach

- Midfacial degloving

- Endoscopic approach

Neck dissections often accompany the abovementioned procedures, where extensive neck involvement is present. Neck dissection is frequently a component of surgical salvage, particularly in the case of regional recurrence.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for nasopharyngeal carcinoma includes the following:

Benign Conditions

- Nasopharyngeal polyposis

- Angiofibromas

- Antro-choanal polyp

- Inverting papilloma

- Adenoid hypertrophy

- Thornwaldt cyst

- Encephalocele

Malignant Lesions

- Lymphoma

- Sarcoma

- Mucosal melanomas

Staging

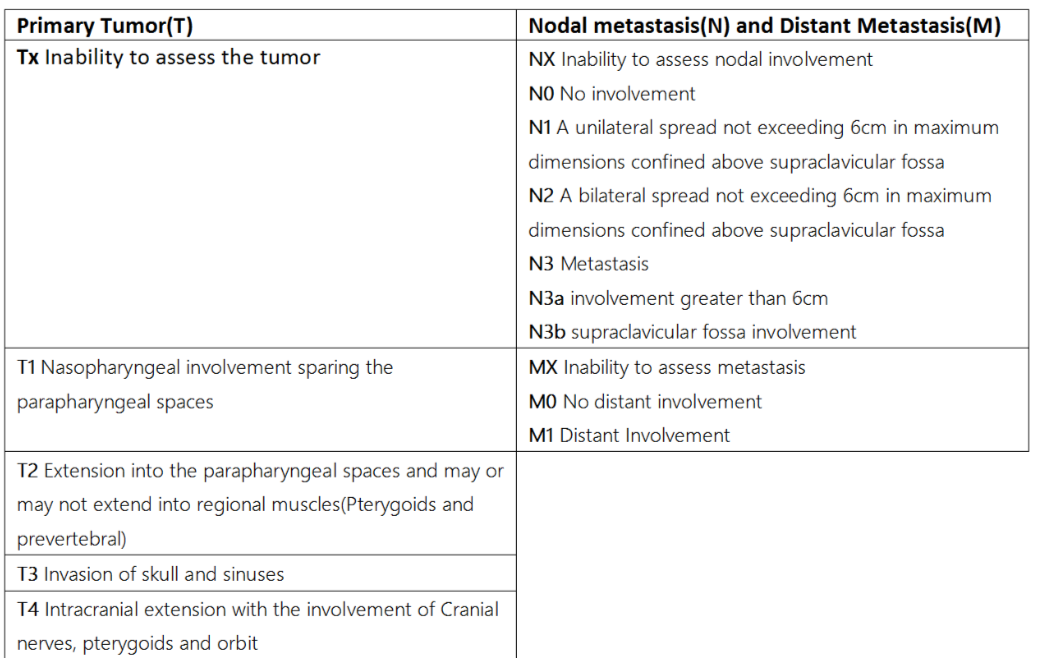

The nuances in imaging techniques and the improved outcomes associated with optimum therapy have caused the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) to reevaluate the staging process in 2018 (see Image. Staging Table).[16] As per the recent guidelines, the TNM staging has been defined as:

Primary Tumor (T)

- T0: No primary tumor identified (but with EBV-positive cervical node)

- Tis: Carcinoma in situ, no invasive tumor present

- T1: Tumor involves nasopharynx, oropharynx, and/or nasal cavity without parapharyngeal involvement

- T2: Tumor extension into the parapharyngeal spaces or adjacent soft tissue (pterygoids, prevertebral muscles)

- T3: Tumor involves bony skull base, pterygoid bones, paranasal sinuses, cervical vertebrae

- T4:Tumor involves intracranial extension, deficits of cranial nerves, hypopharynx, orbit, parotid gland, and/or soft tissue infiltration beyond the lateral surface of the lateral pterygoid

Nodal metastasis (N)

- N0: No involvement

- N1: Unilateral cervical or unilateral or bilateral retropharyngeal node(s), ≤ 6 cm in greatest dimension, all located above the caudal border of the cricoid cartilage

- N2: Bilateral cervical node(s), ≤ 6 cm in greatest dimension, all located above the caudal border of the cricoid cartilage

- N3: Unilateral or bilateral cervical node(s) > 6 cm in greatest dimension or located below the caudal border of the cricoid cartilage

Distant Metastasis (M)

- M0: No distant metastases

- M1: Distant metastases present

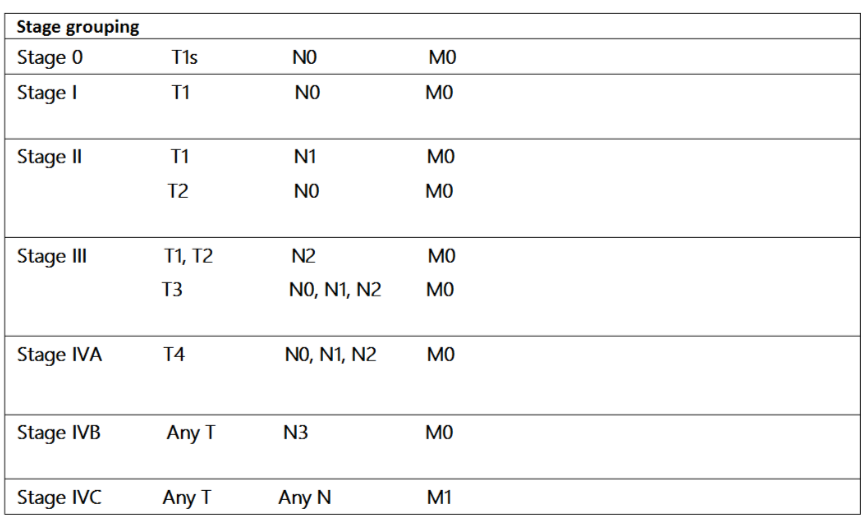

Stage Grouping

- Stage 0: T1s-N0-M0

- Stage I: T1-N0-M0

- Stage II: T1-N1-M0 and T2-N0, N1-M0

- Stage III: T1, T2, T3-N2-M0 and T3-N0, N1, N2-M0

- Stage IVA: T4-any N-M0 and Any T, N3-M0

- Stage IVB: Any T-any N, M1 (see Image. Stage Grouping Table)

Prognosis

The overall prognosis and the 5-year survival rate have improved with improved radiotherapy techniques. This has resulted in reported 5-year survival rates increasing from 25% to 40% historically to approximately 70% in the modern treatment era.[17]

Complications

Obstruction of Eustachian tubes causing otitis media with effusion is the most common complication, but persistent nasal obstruction and obstruction of the oropharyngeal airway are also possible. Intracranial extension and involvement of cranial nerves are debilitating. They can have a lifelong disability even after management, as the return of cranial nerve function is not always possible even after the malignancy has been treated. More than 1 cranial nerve deficit is a poor prognostic sign.[18]

Consultations

Consultations that are typically requested for patients with this condition include the following:

- Otolaryngology - nasopharyngeal biopsy and placement of tympanostomy tube

- Pathology or radiology - FNA of cervical lymph node

- Radiation oncology - definitive treatment

- Hematology/Oncology - concurrent chemotherapy

- Psychiatry - mental health in the setting of a new cancer diagnosis

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients endemic to prevalent areas should be more vigilant regarding the symptoms of the disease. Moreover, the demographics of the Western population with environmental factors (smoking, etc) associated with NPC should also receive education regarding their hazardous effects. Also, the subset of people having genetic susceptibility along with recurrent EBV infection should have a higher index of suspicion for the disease.

Pearls and Other Issues

Key facts to keep in mind about nasopharyngeal carcinoma are as follows:

- NPC is a malignancy having a variable incidence depending on the region.

- Endoscopic biopsy should be the first and foremost step in evaluating the lesion.

- NPC has a high index of susceptibility to radiotherapy, and this forms the mainstay of treatment at nearly every stage

- In advanced cases, chemotherapy is given concomitantly to produce optimum results. The drug of choice is cisplatin.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

After diagnosis, a radiotherapist and oncologist should educate the patient regarding the favorable outcome of strict adherence to the program. Otolaryngology and otolaryngology nurses provide care and education to these patients after nasopharyngeal biopsy and regarding hearing optimization, if Eustachian tube dysfunction is present. Board-certified oncologic pharmacists review prescriptions and check for drug-drug interactions. Oncology specialty nursing staff can administer chemotherapy, assist in post-procedural care and monitoring, and report any concerns to the treating clinicians.

All these interprofessional team members are tasked with keeping meticulous patient records so that everyone involved in the patient's care has the most accurate and updated information, and everyone must maintain open communication lines so interventions can be promptly initiated when needed. Also, patients having the psychological burden of a malignant diagnosis benefit from structured support groups and psychologist sessions, so mental health practitioners should also be part of the interprofessional team.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Video to Play)

Radiologic Imaging Study, Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. Radiologic imaging study of a 53-year-old male patient who had been operated on for a nasopharyngeal carcinoma 5 years ago.

Contributed by M Özdemir, MD

References

Chang ET, Adami HO. The enigmatic epidemiology of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2006 Oct:15(10):1765-77 [PubMed PMID: 17035381]

Du T, Xiao J, Qiu Z, Wu K. The effectiveness of intensity-modulated radiation therapy versus 2D-RT for the treatment of nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS one. 2019:14(7):e0219611. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0219611. Epub 2019 Jul 10 [PubMed PMID: 31291379]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceJicman Stan D, Niculet E, Lungu M, Onisor C, Rebegea L, Vesa D, Bezman L, Bujoreanu FC, Sarbu MI, Mihailov R, Fotea S, Tatu AL. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A new synthesis of literature data (Review). Experimental and therapeutic medicine. 2022 Feb:23(2):136. doi: 10.3892/etm.2021.11059. Epub 2021 Dec 13 [PubMed PMID: 35069817]

Sun L, Wang Y, Shi J, Zhu W, Wang X. Association of Plasma Epstein-Barr Virus LMP1 and EBER1 with Circulating Tumor Cells and the Metastasis of Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. Pathology oncology research : POR. 2020 Jul:26(3):1893-1901. doi: 10.1007/s12253-019-00777-z. Epub 2019 Dec 12 [PubMed PMID: 31832991]

Adoga AA, Kokong DD, Ma'an ND, Silas OA, Dauda AM, Yaro JP, Mugu JG, Mgbachi CJ, Yabak CJ. The epidemiology, treatment, and determinants of outcome of primary head and neck cancers at the Jos University Teaching Hospital. South Asian journal of cancer. 2018 Jul-Sep:7(3):183-187. doi: 10.4103/sajc.sajc_15_18. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30112335]

Cao SM, Simons MJ, Qian CN. The prevalence and prevention of nasopharyngeal carcinoma in China. Chinese journal of cancer. 2011 Feb:30(2):114-9 [PubMed PMID: 21272443]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePeng G, Wang T, Yang KY, Zhang S, Zhang T, Li Q, Han J, Wu G. A prospective, randomized study comparing outcomes and toxicities of intensity-modulated radiotherapy vs. conventional two-dimensional radiotherapy for the treatment of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Radiotherapy and oncology : journal of the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology. 2012 Sep:104(3):286-93. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2012.08.013. Epub 2012 Sep 17 [PubMed PMID: 22995588]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceDenton AJ, Khunger A, Reyes-Corcho A. Case of Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Presenting With Rare Combination of Multiple Cranial Nerve Palsies. Cureus. 2021 Dec:13(12):e20357. doi: 10.7759/cureus.20357. Epub 2021 Dec 12 [PubMed PMID: 35028234]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMo HY, Sun R, Sun J, Zhang Q, Huang WJ, Li YX, Yang J, Mai HQ. Prognostic value of pretreatment and recovery duration of cranial nerve palsy in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Radiation oncology (London, England). 2012 Sep 7:7():149. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-7-149. Epub 2012 Sep 7 [PubMed PMID: 22958729]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBatsakis JG, Solomon AR, Rice DH. The pathology of head and neck tumors: carcinoma of the nasopharynx, Part 11. Head & neck surgery. 1981 Jul-Aug:3(6):511-24 [PubMed PMID: 7251374]

Teoh JW, Yunus RM, Hassan F, Ghazali N, Abidin ZA. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma in dermatomyositis patients: A 10-year retrospective review in Hospital Selayang, Malaysia. Reports of practical oncology and radiotherapy : journal of Greatpoland Cancer Center in Poznan and Polish Society of Radiation Oncology. 2014 Sep:19(5):332-6. doi: 10.1016/j.rpor.2014.02.005. Epub 2014 Jul 15 [PubMed PMID: 25184058]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLee N, Harris J, Garden AS, Straube W, Glisson B, Xia P, Bosch W, Morrison WH, Quivey J, Thorstad W, Jones C, Ang KK. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy with or without chemotherapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma: radiation therapy oncology group phase II trial 0225. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2009 Aug 1:27(22):3684-90. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.9109. Epub 2009 Jun 29 [PubMed PMID: 19564532]

Blanchard P, Nguyen F, Moya-Plana A, Pignon JP, Even C, Bidault F, Temam S, Ruffier A, Tao Y. [New developments in the management of nasopharyngeal carcinoma]. Cancer radiotherapie : journal de la Societe francaise de radiotherapie oncologique. 2018 Oct:22(6-7):492-495. doi: 10.1016/j.canrad.2018.06.003. Epub 2018 Aug 4 [PubMed PMID: 30087054]

Liu J, Yu H, Sun X, Wang D, Gu Y, Liu Q, Wang H, Han W, Fry A. Salvage endoscopic nasopharyngectomy for local recurrent or residual nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a 10-year experience. International journal of clinical oncology. 2017 Oct:22(5):834-842. doi: 10.1007/s10147-017-1143-9. Epub 2017 Jun 10 [PubMed PMID: 28601934]

Hay A, Simo R, Hall G, Tharavai S, Oakley R, Fry A, Cascarini L, Lei M, Guerro-Urbano T, Jeannon JP. Outcomes of salvage surgery for the oropharynx and larynx: a contemporary experience in a UK Cancer Centre. European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology : official journal of the European Federation of Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Societies (EUFOS) : affiliated with the German Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology - Head and Neck Surgery. 2019 Apr:276(4):1153-1159. doi: 10.1007/s00405-019-05295-x. Epub 2019 Jan 21 [PubMed PMID: 30666441]

Amin MB, Greene FL, Edge SB, Compton CC, Gershenwald JE, Brookland RK, Meyer L, Gress DM, Byrd DR, Winchester DP. The Eighth Edition AJCC Cancer Staging Manual: Continuing to build a bridge from a population-based to a more "personalized" approach to cancer staging. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2017 Mar:67(2):93-99. doi: 10.3322/caac.21388. Epub 2017 Jan 17 [PubMed PMID: 28094848]

Li J, Chen S, Peng S, Liu Y, Xing S, He X, Chen H. Prognostic nomogram for patients with Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma incorporating hematological biomarkers and clinical characteristics. International journal of biological sciences. 2018:14(5):549-556. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.24374. Epub 2018 Apr 5 [PubMed PMID: 29805306]

Ho AC, Chan JY, Ng RW, Ho WK, Wei WI. The role of myringotomy and ventilation tube insertion in maxillary swing approach nasopharyngectomy: review of our 10-year experience. The Laryngoscope. 2013 Feb:123(2):376-80. doi: 10.1002/lary.23684. Epub 2012 Sep 5 [PubMed PMID: 22951935]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence