Introduction

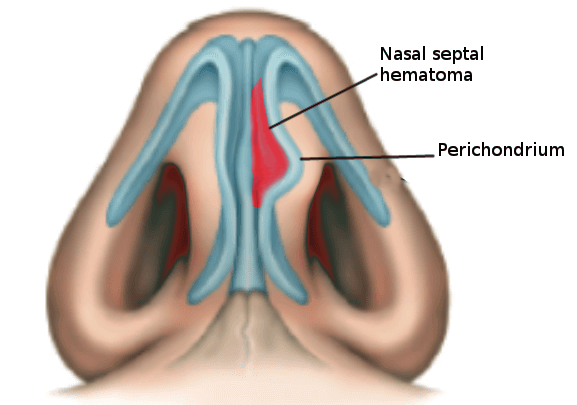

The nose is the most commonly injured facial structure. Most nasal injuries do not require immediate intervention, but trauma resulting in septal hematoma is an exception. A nasal septal hematoma is a rare but serious complication of nasal or facial trauma. It refers to the collection of blood under the mucoperichondrium or mucoperiosteum of nasal septal cartilage or bone. It may be unilateral or bilateral, with the latter being more frequent in the setting of severe trauma.[1][2][3][4]

The key is to prevent the formation of an abscess which can eventually result in a saddle nose deformity or septal perforation, both of which are potentially permanent complications.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

A septal hematoma usually occurs secondary to nasal trauma. The latter can be in the form of sports injuries, road-side accidents, falls, assault or occupational injuries. Even a minor injury can lead to nasal septal hematoma, especially in children. In-fact a nasal septal hematoma without injury should raise the suspicion of child abuse, especially in infants and toddlers. Iatrogenic septal hematoma may arise as a complication of nasal surgeries like septal correction, endoscopic sinus surgery or turbinate surgery. Atraumatic septal hematoma is rarely seen in patients with bleeding diathesis or as an adverse effect of antiplatelet/anticoagulant drugs.[5][6][7]

Epidemiology

A septal hematoma is a rare entity and can occur in any age group. The exact incidence of septal hematoma remains unknown. However, it has been reported to occur in 0.8% to 1.6% of patients with nasal injury attending ear, nose, and throat clinic. Unfortunately, a large number of cases often remain undiagnosed, especially in children, until complications occur.

Pathophysiology

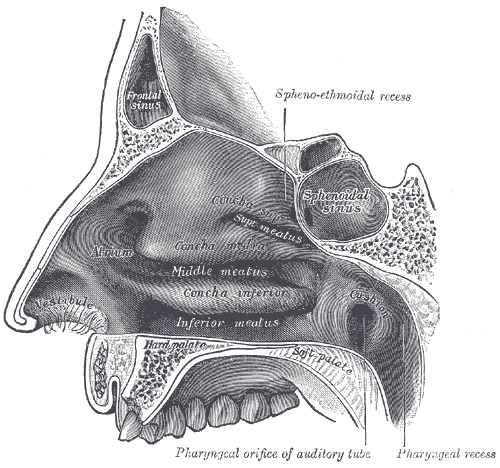

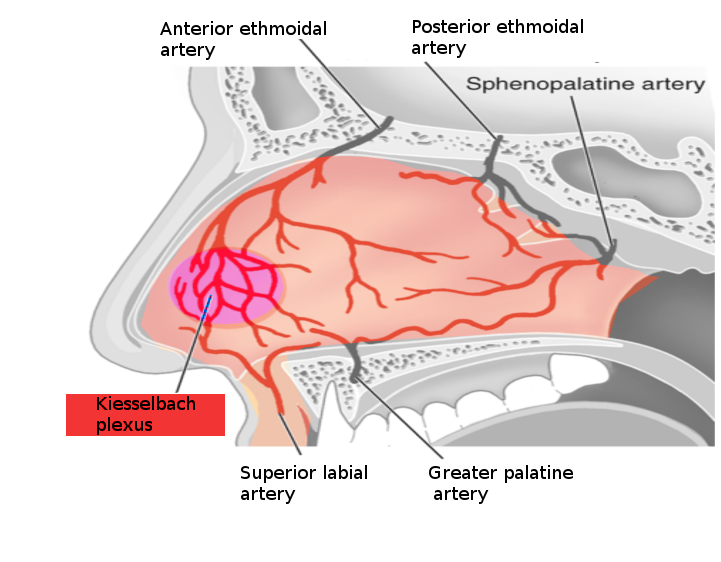

The anterior part of the nasal septum consists of a thin cartilaginous layer with closely adherent mucosa and perichondrium. The nasal septum is about 3-4 mm thick and derives its blood supply from the anterior and posterior ethmoid arteries and the sphenopalatine artery. The area known as Kiesselbach plexus (little area) is found in the anterior inferior third of the nasal septum, where all the key blood vessels anastomose. When the nasal cartilage is fractured, blood can dissect and form hematoma, which may be bilateral.

The exact mechanism underlying the formation of nasal septal hematoma remains controversial. Septal cartilage is an avascular structure, 2 mm to 4 mm thick, which receives its nutrients supply from the overlying perichondrium. Physicians hypothesize that trauma results in sharp buckling forces that pull the closely adherent mucoperichondrium from the underlying cartilage. This causes the rupture of submucosal vessels which ultimately causes a collection of blood between the cartilage and the perichondrium. Hematoma thus formed, results in pressure-related ischaemic changes and the subsequent necrosis of the septal cartilage.

If the trauma is severe enough, the septal cartilage gets fractured, and blood sweeps to the opposite side resulting in a bilateral septal hematoma. This situation is more hazardous as it doubles the compromise on the nutrient supply of septal cartilage and hastens the process of cartilage necrosis.

Hematoma acts as an ideal medium for bacterial proliferation and colonization. If left untreated, it gets infected within 72 hours leading to the formation of a septal abscess.

History and Physical

A nasal hematoma usually presents within the first 24 to 72 hours after trauma. However delayed presentation has also been reported. The most common symptom is the nasal obstruction (95%) which can be either unilateral or bilateral depending on the type of hematoma. Other symptoms include pain (50%), rhinorrhea (25%), and fever (25%). In many cases, symptoms are non-specific. Therefore, a high index of suspicion should be kept especially if a patient presents with nasal deformity and/or nasal pain following trauma. Also if a post-traumatic nasal obstruction does not resolve with a local vasoconstrictive agent or blood clot removal, the possibility of a nasal hematoma should be strongly considered.

Clinical examination is usually confirmatory. It can either be accomplished with a nasal speculum or otoscope. Blood clots, if any should be suctioned. Asymmetry of the septum with bluish or reddish mucosal swelling suggests a hematoma. A newly formed hematoma is not always ecchymotic and can only be picked up by palpation. Direct palpation is carried out by gently inserting the little finger into the patient's nose. A hematoma feels soft and fluctuant in contrast to deviated nasal septum which will be firm and concave on the opposite side. Another important feature of septal hematoma is the lack of reduction in size on the application of decongestant sprays like oxymetazoline 0.05%.

Evaluation

Usually clinical diagnosis. Rarely CT or MRI might be considered if the diagnosis is equivocal on physical exam.

Treatment / Management

A nasal septal hematoma should be drained urgently to avoid undue complications. The procedure is done under local anesthesia. However general anesthesia might be required in apprehensive adults and children.[8][9][10](A1)

Following equipment/instruments should be available before draining a septal hematoma:

- Topical anesthesia

- Light source (head-lamp or otoscope)

- Nasal speculum

- Suction apparatus (Frazier suction tip)

- Gloves

- Needle, 18-20 gauge (Ga)

- Syringe, five mL

- Scalpel, No. 11 blade or 15 blade

- Commercially produced nasal tampon

- Gelfoam (absorbable gelatin)

- Surgicel (oxidized cellulose)

- Small Penrose drain

The patient should lie in the reclining position with the head end of the table slightly raised. Small hematomas can be aspirated with an 18-Ga to 20 -Ga needle. Larger hematomas are drained by incising the mucosa over the most fluctuant area. The incision is given in the anteroposterior direction parallel to the nasal floor. In the case of a bilateral hematoma, a staggered incision is made to avoid through and through the septal perforation. The clot is suctioned, and saline irrigation is carried out on an 18-Ga to 20-Ga catheter. A small piece of the mucosa is excised from the incision edge for better drainage and the prevention of premature closure. A small Penrose drain is placed into the opened hematoma cavity and secured with a suture. The nose is packed on both sides to prevent the re-accumulation of blood. Systemic antibiotics are prescribed to prevent serious, infective complications. Pack and drain are usually kept in situ for 2 to 3 days and is removed only when there is no further drainage for at least 24 hours. Patients should be kept on regular follow up to prevent delayed complications.

Differential Diagnosis

- Angiofibroma

- Adenoid hypertrophy

- Chronic sinusitis

- Chondromas

- Hemangioma

- Malignancies

- Nasal polyps

- Papillomas

- Pyogenic granulomas

- Rhinitis

- Septal abscess

- Septal deformities

Complications

A nasal septal abscess is a major complication of a septal hematoma. The abscess can easily spread to adjacent structures including the sinuses and the brain.

The expanding hematoma can cause avascular necrosis of the cartilage and collapse, leading to a saddle nose deformity.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

The patient must be seen in the clinic within 24-48 hours to ensure that the hematoma has been drained. The packing may need to be removed to examine the nose.

Pearls and Other Issues

Complications are bound to occur in untreated or improperly treated hematomas. A septal abscess is the most common acute complication of a septal hematoma. If left untreated, the infection can spread to the nearby anatomical structures like paranasal sinuses, orbit or intracranial structures, through the venous draining the mid-face. Avascular necrosis and secondary infection can lead to the collapse of septal cartilage causing various types of nasal deformities. In children, destruction can cause an altered growth of mid-face and permanent facial deformity.[11][12]

Potential complications associated with untreated septal hematoma (according to the site of occurrence):

A. Local

- Septal abscess

- Saddle nose

- Deviated nasal septum

- Nasal valve collapse

- Sinusitis

- Facial cellulitis

- Nasal vestibulitis

B. Systemic

- Sepsis

- Bacteremia

C. Orbital

- Orbital cellulitis

- Sub-periosteal abscess

- Orbital abscess

D. Intracranial Complications

- Cavernous sinus thrombosis

- Epidural abscess

- Meningitis

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Nasal septal hematomas are not uncommon because of facial trauma. These injuries are best managed by an interprofessional team that includes a plastic surgeon, ENT surgeon. general surgeon, trauma surgeon emergency department physician and specialty nurses. Missed or delayed diagnosis can lead to both local and systemic complications that carry high morbidity. A nasal septal hematoma should be suspected with any type of facial injury and appropriate referral made to the ENT or plastic surgeon. Clinicians in the emergency department should consult with an ENT surgeon if there is any suspicion of the diagnosis or management. With prompt drainage, the outcomes are good in most people.[11]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Henry M, Hern HG. Traumatic Injuries of the Ear, Nose and Throat. Emergency medicine clinics of North America. 2019 Feb:37(1):131-136. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2018.09.011. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30454776]

Nassar AT. Intracorporeal Septorhinoplasty: Technique and Outcome. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2018 Nov:29(8):2055-2057. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000004782. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30277942]

Tasca I, Compadretti GC, Losano TI, Lijdens Y, Boccio C. Extracorporeal septoplasty with internal nasal valve stabilisation. Acta otorhinolaryngologica Italica : organo ufficiale della Societa italiana di otorinolaringologia e chirurgia cervico-facciale. 2018 Aug:38(4):331-337. doi: 10.14639/0392-100X-1525. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30197424]

Howell J, Costanzo RM, Reiter ER. Head trauma and olfactory function. World journal of otorhinolaryngology - head and neck surgery. 2018 Mar:4(1):39-45. doi: 10.1016/j.wjorl.2018.02.001. Epub 2018 Mar 14 [PubMed PMID: 30035260]

Dąbrowska-Bień J, Skarżyński PH, Gwizdalska I, Łazęcka K, Skarżyński H. Complications in septoplasty based on a large group of 5639 patients. European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology : official journal of the European Federation of Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Societies (EUFOS) : affiliated with the German Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology - Head and Neck Surgery. 2018 Jul:275(7):1789-1794. doi: 10.1007/s00405-018-4990-8. Epub 2018 May 16 [PubMed PMID: 29770875]

de Gabory L, Sowerby LJ, DelGaudio JM, Al-Hussaini A, Hopkins C, Serrano E. International survey and consensus (ICON) on ambulatory surgery in rhinology. European annals of otorhinolaryngology, head and neck diseases. 2018 Feb:135(1S):S49-S53. doi: 10.1016/j.anorl.2017.12.010. Epub 2018 Feb 3 [PubMed PMID: 29398505]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRodriguez DP, Orscheln ES, Koch BL. Masses of the Nose, Nasal Cavity, and Nasopharynx in Children. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2017 Oct:37(6):1704-1730. doi: 10.1148/rg.2017170064. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29019747]

Kim JS, Kwon SH. Is nonabsorbable nasal packing after septoplasty essential? A meta-analysis. The Laryngoscope. 2017 May:127(5):1026-1031. doi: 10.1002/lary.26436. Epub 2016 Nov 30 [PubMed PMID: 27900768]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAgrawal N, Brayley N. Audit of nasal fracture management in accident and emergency in a district general hospital. Journal of evaluation in clinical practice. 2007 Apr:13(2):295-7 [PubMed PMID: 17378878]

Wang WW, Dong BC. Comparison on effectiveness of trans-septal suturing versus nasal packing after septoplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology : official journal of the European Federation of Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Societies (EUFOS) : affiliated with the German Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology - Head and Neck Surgery. 2017 Nov:274(11):3915-3925. doi: 10.1007/s00405-017-4709-2. Epub 2017 Sep 15 [PubMed PMID: 28917002]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceJohnson MD. Management of Pediatric Nasal Surgery (Rhinoplasty). Facial plastic surgery clinics of North America. 2017 May:25(2):211-221. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2016.12.006. Epub 2017 Feb 21 [PubMed PMID: 28340652]

Kopacheva-Barsova G, Arsova S. The Impact of the Nasal Trauma in Childhood on the Development of the Nose in Future. Open access Macedonian journal of medical sciences. 2016 Sep 15:4(3):413-419 [PubMed PMID: 27703565]