Introduction

Shoulder dystocia is a clinically important complication in up to 3% of all normal vaginal deliveries, even those without risk factors. Shoulder dystocia occurs when the anterior shoulder of the fetus becomes lodged behind the maternal pubic symphysis or the posterior shoulder becomes lodged behind the maternal sacral promontory. [1][2][3] The impaction of either shoulder impedes the descent of the fetal body and expulsion of the fetus after delivery of the fetal head. The incidence of shoulder dystocia increases, however, as the size of the infant increases. For example, infants weighing <4,000 g are noted to have an incidence of about 1%, infants weighing 4,000 to 4,500 g have an incidence of about 5%, and infants weighing >4,500 g have an incidence of approximately 9% to 10%.[4][5]

Several maneuvers may relieve shoulder dystocia; the simplest is the McRoberts maneuver. Current guidelines from both the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) recommend using the McRoberts maneuver initially to resolve a shoulder dystocia since it is easy, logical, quick, and effective.[1] Studies have shown that when used alone, the McRoberts maneuver can resolve up to 42% of shoulder dystocias without additional obstetric maneuvers.[2]

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

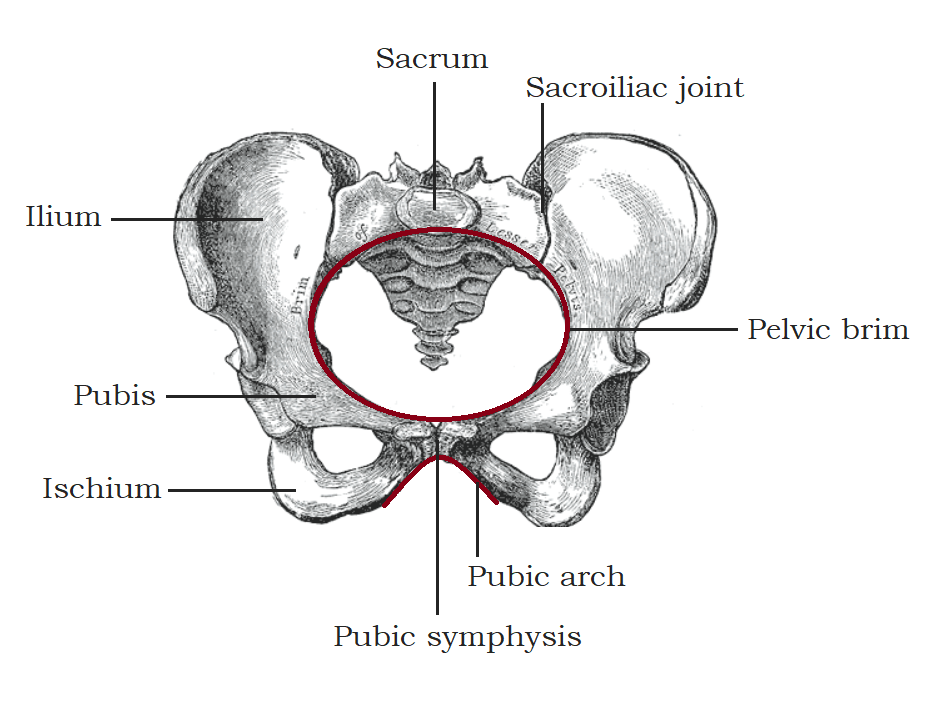

Familiarity with the boney female pelvis is essential in understanding how shoulder dystocia develops and provides insight into why the correct application of the McRoberts maneuver can relieve shoulder dystocia.

Composition of the Pelvic Girdle

The pelvic girdle is comprised of 4 bones and 3 joints. The bones consist of the sacrum, the coccyx, and the two innominate bones formed by the fusion of the ilium, ischium, and pubic rami.[6] The joints include the sacroiliac joints bilaterally located between the sacrum and each ilium, and the pubic symphysis joint, where the right and left pubic rami meet anteriorly.[6]

Pelvic Spaces: The Lesser Pelvis and Greater Pelvis

The space enclosed by the pelvic girdle has a bowl-like shape and is divided into the greater and the lesser pelvis. The greater pelvis (ie, false pelvis) refers to the superior portion between the iliac wings. The lesser pelvis (ie, true pelvis) lies inferior to the greater pelvis and is located between the sacrum and coccyx posteriorly and the pubic and ischial bones anteriorly and laterally.[7]

A somewhat round, bony ridge known as the pelvic brim is at the boundary between the greater and lesser pelvis; it is comprised of the sacral promontory, the arcuate line on the ilium, and the superior border of the pubic rami. The pelvic brim circumscribes an opening known as the pelvic inlet. The pelvic inlet is thus the "entrance" into the lesser, or true, pelvis. The pelvic outlet is the opening at the lower margin of the lesser pelvis. This margin is made up posteriorly of the coccyx, posterolaterally of the sacrotuberous ligaments, laterally of the ischial tuberosities, and anteriorly of the pubic arch. Thus, during labor and delivery, the fetus must descend through the pelvic inlet, traverse the lesser pelvis, and emerge through the pelvic outlet.[8]

Pelvimetry and Pelvic Diameters

Pelvimetry is the measured assessment of the dimensions of the pelvis; it is most often used to evaluate the risk of cephalopelvic disproportion in a pregnant individual. The 3 diameters primarily used in pelvimetry to assess the pelvic inlet are the anterior-posterior (A-P), the transverse, and the oblique diameters. Furthermore, the pelvic inlet's A-P diameter (ie, conjugate) can be measured in 3 different ways. By measuring the distance from 3 separate points along the pubic symphysis to the central point of the sacral promontory, various aspects of the A-P diameter, also known as A-P conjugates, can be assessed. These conjugates are the anatomical, diagonal, and obstetric conjugates.[8]

The anatomic conjugate is the distance between the sacral promontory and the superior margin of the pubic symphysis. Katanozaka et al. reported that parturients with an anatomic conjugate of <12 cm were more likely to have a cesarean delivery due to labor dystocia than those with larger conjugates.[9] The diagonal conjugate is the distance between the sacral promontory and the inferior margin of the pubic symphysis; it is the only conjugate that can be directly assessed on a physical examination. This is done by palpating the sacral promontory with the middle finger on a vaginal exam and then noting the distance from the fingertip to the point the examining hand contacts the pubic arch, which is approximately 12.5 cm on average.[8]

The obstetric (ie, true) conjugate is the distance between the sacral promontory and the widest portion of the pubic symphysis, located between the superior and inferior margins of the symphysis. The obstetric conjugate represents the smallest fixed distance through the pelvic inlet.[9] Although it cannot be measured directly on physical exam, it can be estimated by measuring the diagonal conjugate and subtracting 1 to 2 cm; the average obstetric conjugate measures approximately 10.5 cm. Some studies have demonstrated ultrasound imaging as an effective, safe, and simple way to assess the obstetric conjugate antenatally to identify patients who should be delivered by cesarean section due to a high risk for cephalopelvic disproportion.[9] Current guidelines, however, generally do not recommend making decisions regarding the mode of delivery based on pelvimetry assessments, as a Cochrane review found no evidence that pelvimetry imaging assessment improved outcomes.[9][10]

Fetal Rotation Through the Lesser Pelvis

The obstetric conjugate in the average gynaecoid pelvis is approximately 11.5 to 12 cm, while the average transverse diameter is typically slightly larger at 13 cm.[11] The largest diameters of the fetal head are in the A-P plane, while the largest diameter of the fetal shoulders is in the transverse plane. For the largest diameters of the fetal head and shoulders to pass through the larger transverse diameter of the maternal pelvis, the fetus must rotate through the true pelvis.

The fetal head typically passes through the pelvic inlet in a transverse position (ie, facing one of the maternal sides). The fetus then internally rotates, more directly aligning its head and shoulders in an A-P orientation (ie, facing either the maternal abdomen or back), which allows its bisacromial diameter to align with the transverse diameter of the maternal pelvis. The fetal head then extends with delivery and restitutes, realigning the fetal head, shoulders, and rest of the body, which represents an external rotation. In some cases, especially with larger infants, the fetal shoulders get stuck behind the bones of the pelvic inlet while attempting to rotate, resulting in a shoulder dystocia.

Changes in Pelvic Alignment During McRoberts Maneuver

The McRoberts maneuver involves sharply flexing the parturient's legs to the maternal abdomen; this increases pelvic conjugates, resulting in a more open pelvic outlet.[1][5] It also causes a cephalad rotation of the pubic symphysis; this results in a significant increase in the angle of inclination (ie, the angle relative to the x-axis) between the superior border of the pubic symphysis and the superior border of the sacral promontory.[12] The angle between L5 and the sacral promontory flattens as the pelvis rotates with the McRoberts maneuver. As the sacral promontory flattens, the posterior shoulder of the fetus has additional space to move posteriorly and inferiorly into the true pelvis. Combined with the cephalad rotation of the pubic symphysis anteriorly, this allows the anterior shoulder to drop out from under the pubic symphysis, especially if suprapubic pressure is applied simultaneously, reducing stretch on the fetal brachial plexus, and facilitating delivery.[13]

Flattening the sacral promontory also enables the force produced by spontaneous uterine contractions to become more effective by aligning the fetus with the maximal expulsive uterine force vectors.[14][15] Additionally, the position can significantly increase the intrauterine pressure generated during contractions and make maternal pushing efforts more effective; this is hypothesized to occur because the position brings the uterus closer to the diaphragm, which electromyographic studies have shown has a far greater impact than the rectus muscles on generating increased intraabdominal and intrauterine pressure during Valsalva.[14] Therefore, when applied during contractions and maternal pushing efforts, the McRoberts maneuver significantly increases expulsive force, reducing mechanical resistance and facilitating delivery.[14]

Effect of Shoulder Dystocia on Fetal Oxygenation

After delivery of the fetal head, the fetal trunk, including the chest, abdomen, and umbilical cord, becomes compressed within the vaginal canal resulting in decreased fetal oxygenation due to reduced blood flow through the umbilical cord. Additionally, the compression prevents the fetus from expanding its lungs effectively until the body is fully delivered.[11] Consequently, rapid relief of shoulder dystocia to avoid fetal asphyxiation is critical in reducing infant morbidity and mortality.

Indications

The McRoberts maneuver is recommended as a first-line maneuver whenever shoulder dystocia is suspected. Suprapubic pressure, another maneuver recommended when managing a shoulder dystocia, may be performed simultaneously. The McRoberts maneuver is indicated when clinical signs of a shoulder dystocia are present, including the retraction of the fetal head against the maternal perineum after its delivery (ie, "turtle sign") or failure of the anterior fetal shoulder to deliver with gentle traction.[1] Additionally, some clinicians will perform the maneuver prophylactically before delivery of the fetal head in patients with risk factors for shoulder dystocia.[11]

Risk Factors for Shoulder Dystocia

Unfortunately, shoulder dystocia can be difficult to predict and cannot be reliably prevented.[1] The most significant risk factors are maternal diabetes, previous shoulder dystocia, and fetal macrosomia. Maternal diabetes causes elevated glucose levels in the fetus, which stimulates it to produce excess insulin, insulin-like growth factors, and growth hormone, potentially leading to large for gestational age infants or infants with larger shoulders and increased abdominal-to-head circumference ratios.[16] Larger infants may have difficulty traversing the fixed diameters of the maternal pelvis.[11] Despite this, the majority of shoulder dystocias still occur in nondiabetic mothers with average-size infants, while many patients with diabetes or macrosomic infants do not have shoulder dystocias.[1]

For patients with a history of shoulder dystocia or an infant with a brachial plexus injury in a prior pregnancy, the risk of recurrence is estimated to be at least 10%. [1] For this reason, primary elective cesarean delivery may be considered after careful evaluation of the entire clinical picture.[1] For patients who elect to proceed with a trial of labor, the delivering team needs to maintain a heightened awareness and be prepared for the possibility of recurrent shoulder dystocia. Prophylactic use of the McRoberts maneuver may be considered in these situations. No advantage, though, has been observed with its use before the appearance of clinical signs suggestive of shoulder dystocia. However, there are minimal risks in using the maneuver prophylactically at the time of delivery.[4]

Additional risk factors for shoulder dystocia include prior delivery of a large birthweight infant, increased maternal weight gain, maternal obesity, and intrauterine fetal death.[17][5][3] Intrapartum conditions that may signal the possibility of impending shoulder dystocia include a prolonged second stage of labor, failure of the fetal head to descend, and need for the operative (ie, forceps or vacuum) vaginal delivery of the fetal head.[2]

Contraindications

McRoberts maneuver is safe for the vast majority of parturients. The only relative contraindications are hip, pelvic, or spinal abnormalities (eg, deformities, fractures) limiting the safe hyperflexion of the thighs. Additionally, the procedure may be more challenging for patients with difficulty moving into the position, including those with obesity, neuromuscular disorders, severe arthritis, or other degenerative joint disorders.[18]

Equipment

No specific equipment is required to perform the McRoberts maneuver. However, it is helpful to position the labor bed at a low height and have step stools available on both sides of the patient's bed. This allows the delivering clinician and the obstetric personnel assisting with the maneuver to physically optimize their performance of this and any additional maneuvers that may be necessary.[1]

Personnel

In addition to the delivering clinician, the McRoberts maneuver typically requires two assistants, one to hold each maternal leg. It is best if these assistants are trained obstetric professionals (eg, a labor and delivery nurse or second physician); adequate personnel should be present in the delivery room for any patients with potential risk factors.[1] However, because the maneuver is relatively simple, in unexpected cases or when trained assistants are unavailable, the parturient and any available labor support individuals in the room can be instructed on how to assist with the maneuver until additional trained help arrives.

Preparation

Before delivery, obstetric personnel should be informed of the increased potential for shoulder dystocia in any patient with obstetrical risk factors for shoulder dystocia. The briefing should include nursing staff, obstetricians, anesthesiologists, pediatricians, and any other personnel caring for the patient and her infant so that they are aware and can be prepared to manage a shoulder dystocia and urgent neonatal complications promptly, should they occur. Furthermore, this allows additional personnel to be available to assist if needed.[19] Additionally, advanced preparation (eg, stools available on both sides of the bed, adequate personnel in the room, and the bed already at a comfortable height) assists in the calm implementation of the maneuver at the first signs of shoulder dystocia.[1]

Regular practice in managing emergencies through simulations can help ensure that all obstetric healthcare team members are adequately trained in performing shoulder dystocia maneuvers. Participation in emergency drills can identify clinical errors frequently made during emergencies, increase effective communication between healthcare team members, and reinforce proper protocol. Several studies have shown that simulation training also reduces maternal and neonatal morbidity.[1][19]

Technique or Treatment

Before performing any maneuvers, the delivering clinician should inform the other healthcare team members in the room that a shoulder dystocia is present. This allows the obstetrical team to position themselves correctly, call for additional help, and begin proper documentation, including keeping track of the time and each maneuver performed.[1]

The McRoberts Maneuver

The McRoberts maneuver is simple but is best performed by two assistants other than the delivering physician or midwife. One assistant should be positioned by each leg of the patient and take hold, supporting the foot/ankle and knee. The two assistants then push the maternal feet cephalad so that the thighs rest on the anterolateral aspects of the maternal abdomen. This action results in hyperflexion of the maternal hips to an angle of approximately 135° relative to the supine position.[12][14] The thighs are also usually abducted somewhat, though a recent study suggested that this does not significantly impact the flattening of the sacrum or the anterior rotation of the pubic symphysis and is less important.[18] If no assistants are available, the parturient can be instructed to pull her knees as hard as she can up toward her armpits.[12]

Meanwhile, the delivering clinician stays at the perineum and attempts to effect delivery with gentle downward traction on the fetal head, which, according to ACOG, should be aligned with "the fetal cervico-thoracic spine...along a vector estimated to be 25° to 45° below the horizontal plane when the laboring patient is in a lithotomy position."[1] Lateral traction should be avoided.

The maneuver is usually attempted for approximately 30 seconds. If delivery has not occurred during this time with gentle traction on the fetal head, the team should move on to other maneuvers (eg, suprapubic pressure, delivery of the posterior arm).[1] Prolonged or sustained use of the position should be avoided due to the potential risk of maternal lower extremity neuropathy from femoral nerve compression.[5]

Suprapubic Pressure

Though not considered part of the McRoberts maneuver, suprapubic pressure is an additional maneuver that is frequently simultaneously applied when the McRoberts maneuver is performed. The application of suprapubic pressure attempts to dislodge and internally rotate the impacted fetal shoulder (ie, the fetal shoulder should be rotated toward its sternum rather than away from it). This pressure can be applied with the palm or fist and should be directed at a downward and slightly oblique angle toward the patient's right or left side, depending on the position of the fetus. [1][2] The delivering clinician should know or attempt to identify the orientation of the fetus and communicate to the assistants the direction in which suprapubic pressure should be applied and who should apply it based on where the assistants are standing.

For example, if the infant is in the right occiput anterior (ROA) position, facing down and slightly toward the left maternal leg, then it is the left fetal shoulder that is impacted under the pubic symphysis. Therefore, the fetus oriented in this way should be rotated in a clockwise direction. This is best accomplished by the assistant holding the maternal right leg, who can more easily apply the suprapubic pressure by pushing down and slightly away from themselves toward the patient's left hip. Conversely, if the infant is in the left occiput anterior (LOA) position, the assistant holding the patient's left leg should apply the pressure directed slightly toward the maternal right hip, attempting to rotate the fetus in a counterclockwise direction. If the fetal position is unknown, the assistant may begin by pushing straight down if the delivering clinician requests.

Complications

Maternal Complications

Complications are rare when the McRoberts position is used briefly during the management of a shoulder dystocia. However, lower extremity neuropathies in the parturient are possible, though they are typically associated with prolonged use of the position. Hyperflexion of the hip resulting in compression of the femoral nerve or the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve beneath the inguinal ligament can lead to maternal lower extremity neuropathies.[5] Clinically, femoral neuropathy presents with ipsilateral weakness in the quadriceps, causing decreased hip flexion and knee extension; adduction, however, is typically spared because it is mediated by the obturator rather than the femoral nerve. Injury to the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve typically presents as ipsilateral paresthesias, sensory loss, and, potentially, pain radiating down the lateral thigh. Conservative therapy is usually adequate, including physical therapy, avoiding positions that worsen nerve compression, and possibly, neuropathic agents.[20][21]

Symphyseal separation and sacroiliac joint pain of the pelvic girdle are rare complications that have been described after prolonged use of the McRoberts maneuver due to excessive abduction of the hips, combined with strong intrapelvic pressures.[1] Management is usually conservative and includes pelvic girdle support belts, physical therapy to improve pelvic girdle stabilization, and analgesics; symptoms typically improve within 1 to 3 months postpartum, though some patients may develop chronic pain.[22][23] Due to the potential risk for complications, prophylactically pushing in the McRoberts position for prolonged periods, even for patients at high risk for shoulder dystocia, should be avoided.

Neonatal Complications

The rate of neonatal injury due to the McRoberts maneuver is very low. Limited studies have shown similar rates of neonatal morbidity between various shoulder dystocia maneuvers; the rate of injury increases with each maneuver used, however.[24][25]

Neonatal risks associated with shoulder dystocia include traumatic injuries, asphyxia, and death.[1][3][26] Traumatic injuries occur during approximately 10% to 20% of shoulder dystocias, including brachial plexus neuropathy and clavicle and humerus fractures.[1] Severe neonatal complications (eg, fetal asphyxia and hypoxic encephalopathy) can occur even with head-to-body delivery times of <5 minutes. However, neonatal morbidity (eg, respiratory depression or brachial plexus injury) is more prevalent with protracted shoulder dystocias or when using >5 maneuvers.[25][1]

Clinical Significance

The McRoberts maneuver is the first that should be performed in the management of shoulder dystocia due to its simplicity and effectiveness.[1] This maneuver alone resolves up to 42% of shoulder dystocia, and approximately 54% may be resolved if the maneuver is combined with suprapubic pressure.[12]

Due to the interruption in fetal oxygenation that may occur between the delivery of the fetal head and body, the obstetric team needs to work together effectively using established communication methods and algorithms to resolve the dystocia and reduce infant morbidity and mortality. Additionally, the McRoberts maneuver often results in the delivery of the fetal shoulder quickly, which helps to prevent a protracted shoulder dystocia and thus can help reduce the incidence of neonatal complications, including brachial plexus injuries.[26]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

ACOG recommends developing an obstetric rapid response team and protocols that can be instituted based on clinical triggers.[19][26] This team should include obstetric clinicians and nurses, anesthesia personnel, and neonatal team members who will care for the infant immediately after delivery. Hospital guidelines should also identify and address the need for additional personnel (eg, operating room technicians, blood bank and laboratory staff, and page-system operators).[19] Suspected shoulder dystocia is an appropriate indication to summon a rapid response team if the dystocia is not resolved rapidly.

Effectively performing the McRoberts maneuver to manage a shoulder dystocia is a team effort. This maneuver should be practiced regularly with simulation training by all personnel that may be present in a delivery room, including physicians, midwives, nurses, technicians, and trainees.[26][19][27] This training should focus on correctly performing the maneuver and practicing clear, standardized communication between team members. Regular practice in managing emergencies through simulations can help ensure that all obstetric healthcare team members are adequately trained in their respective roles when performing shoulder dystocia maneuvers. Participation in emergency drills can identify clinical errors frequently made during emergencies, increase effective communication between healthcare team members, and reinforce proper protocol. Several studies have shown that simulation training also reduces maternal and neonatal morbidity.[1][19][26]

Additionally, teams should always discuss the potential for a shoulder dystocia in patients with risk factors before delivery. Advanced consideration and planning will allow team members to be mentally and physically prepared to act quickly as needed. The delivering clinician should assess the fetal position during pushing and clearly communicate before delivery of the fetal head which direction suprapubic pressure should be applied in case shoulder dystocia becomes apparent.

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Interventions

Obstetrical nurses are often the team members who position the patient when the McRoberts maneuver is performed; therefore, they need to be intimately familiar with the risk factors for shoulder dystocia and the indications of the maneuver. Accurate knowledge of how to respond when shoulder dystocia is identified and how to assist in performing each maneuver is also essential.

Preparing in anticipation of a shoulder dystocia in those at high risk is critical, including having step stools on both sides of the patient's bed, ensuring that additional obstetric clinicians are available, and assigning roles to trained staff members if shoulder dystocia develops. As a result, obstetrical team members can pay careful attention to the delivering clinician during the delivery of the fetal head and immediately move the patient into McRoberts position and lower the bed when suspicion of shoulder dystocia is communicated. Furthermore, the exact time of delivery of both the fetal head and the shoulders should be documented; as with other "code" situations, obstetrical staff should be assigned to dedicated roles (eg, documentation or "runners" to assist as needed).[1]

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Monitoring

Postpartum nursing staff should monitor patients for signs or symptoms of potential complications after a delivery complicated by shoulder dystocia in which the McRoberts maneuver was used. This includes difficulty standing up from a seated position or ambulation due to potential femoral neuropathy; sensory deficits in the thighs; or pain at the pubic symphysis or sacroiliac joints, especially in an upright position. These patients should be monitored more closely for falls and be offered appropriate conservative treatments, such as heat or ice packs, analgesics, or support belts. Additionally, all team members caring for the infant should carefully assess the infant for signs of brachial plexus injury and other complications related to shoulder dystocia.[1]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

. Practice Bulletin No 178: Shoulder Dystocia. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2017 May:129(5):e123-e133. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002043. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28426618]

Hill DA, Lense J, Roepcke F. Shoulder Dystocia: Managing an Obstetric Emergency. American family physician. 2020 Jul 15:102(2):84-90 [PubMed PMID: 32667171]

Harari Z, Zamstein O, Sheiner E, Wainstock T. Shoulder Dystocia during Delivery and Long-Term Neurological Morbidity of the Offspring. American journal of perinatology. 2021 Feb:38(3):278-282. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1696675. Epub 2019 Sep 6 [PubMed PMID: 31491802]

Athukorala C, Middleton P, Crowther CA. Intrapartum interventions for preventing shoulder dystocia. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2006 Oct 18:2006(4):CD005543 [PubMed PMID: 17054263]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBothou A, Apostolidi DM, Tsikouras P, Iatrakis G, Sarella A, Iatrakis D, Peitsidis P, Gerente A, Anthoulaki X, Nikolettos N, Zervoudis S. Overview of techniques to manage shoulder dystocia during vaginal birth. European journal of midwifery. 2021:5():48. doi: 10.18332/ejm/142097. Epub 2021 Oct 20 [PubMed PMID: 34723155]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWei JT, De Lancey JO. Functional anatomy of the pelvic floor and lower urinary tract. Clinical obstetrics and gynecology. 2004 Mar:47(1):3-17 [PubMed PMID: 15024268]

Manandhar B, Shrestha E. Gynaecoid Pelvis among Female Patients Attending Department of Radiology of a Tertiary Care Centre: A Descriptive Cross-sectional Study. JNMA; journal of the Nepal Medical Association. 2023 Apr 1:61(260):366-369. doi: 10.31729/jnma.8127. Epub 2023 Apr 1 [PubMed PMID: 37208876]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSiccardi MA, Imonugo O, Arbor TC, Valle C. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Pelvic Inlet. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30085610]

Di Pasquo E, Volpe N, Labadini C, Morganelli G, Di Tonto A, Schera GBL, Rizzo G, Frusca T, Ghi T. Antepartum evaluation of the obstetric conjugate at transabdominal 2D ultrasound: A feasibility study. Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scandinavica. 2021 Oct:100(10):1917-1923. doi: 10.1111/aogs.14226. Epub 2021 Jul 26 [PubMed PMID: 34240404]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePattinson RC, Cuthbert A, Vannevel V. Pelvimetry for fetal cephalic presentations at or near term for deciding on mode of delivery. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2017 Mar 30:3(3):CD000161. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000161.pub2. Epub 2017 Mar 30 [PubMed PMID: 28358979]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMenticoglou S. Shoulder dystocia: incidence, mechanisms, and management strategies. International journal of women's health. 2018:10():723-732. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S175088. Epub 2018 Nov 9 [PubMed PMID: 30519118]

Gherman RB, Tramont J, Muffley P, Goodwin TM. Analysis of McRoberts' maneuver by x-ray pelvimetry. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2000 Jan:95(1):43-7 [PubMed PMID: 10636500]

Gonik B, Zhang N, Grimm MJ. Prediction of brachial plexus stretching during shoulder dystocia using a computer simulation model. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2003 Oct:189(4):1168-72 [PubMed PMID: 14586372]

Buhimschi CS, Buhimschi IA, Malinow A, Weiner CP. Use of McRoberts' position during delivery and increase in pushing efficiency. Lancet (London, England). 2001 Aug 11:358(9280):470-1 [PubMed PMID: 11513914]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGonik B, Allen R, Sorab J. Objective evaluation of the shoulder dystocia phenomenon: effect of maternal pelvic orientation on force reduction. Obstetrics and gynecology. 1989 Jul:74(1):44-8 [PubMed PMID: 2733940]

. Macrosomia: ACOG Practice Bulletin, Number 216. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2020 Jan:135(1):e18-e35. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003606. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31856124]

Dandolu V, Lawrence L, Gaughan JP, Grotegut C, Harmanli OH, Jaspan D, Hernandez E. Trends in the rate of shoulder dystocia over two decades. The journal of maternal-fetal & neonatal medicine : the official journal of the European Association of Perinatal Medicine, the Federation of Asia and Oceania Perinatal Societies, the International Society of Perinatal Obstetricians. 2005 Nov:18(5):305-10 [PubMed PMID: 16390789]

Desseauve D, Fradet L, Gherman RB, Cherni Y, Gachon B, Pierre F. Does the McRoberts' manoeuvre need to start with thigh abduction? An innovative biomechanical study. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2020 May 4:20(1):264. doi: 10.1186/s12884-020-02952-6. Epub 2020 May 4 [PubMed PMID: 32366292]

. Committee opinion no. 590: preparing for clinical emergencies in obstetrics and gynecology. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2014 Mar:123(3):722-725. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000444442.04111.c6. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24553170]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAgostini J, Goasguen N, Mosnier H. Patient positioning in laparoscopic surgery: tricks and tips. Journal of visceral surgery. 2010 Aug:147(4):e227-32. doi: 10.1016/j.jviscsurg.2010.07.010. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20920906]

Gibelli F, Ricci G, Sirignano A, Bailo P, De Leo D. Iatrogenic femoral nerve injuries: Analysis of medico-legal issues through a scoping review approach. Annals of medicine and surgery (2012). 2021 Dec:72():103055. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2021.103055. Epub 2021 Nov 10 [PubMed PMID: 34815865]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHeath T, Gherman RB. Symphyseal separation, sacroiliac joint dislocation and transient lateral femoral cutaneous neuropathy associated with McRoberts' maneuver. A case report. The Journal of reproductive medicine. 1999 Oct:44(10):902-4 [PubMed PMID: 10554757]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRobinson HS, Vøllestad NK, Veierød MB. Clinical course of pelvic girdle pain postpartum - impact of clinical findings in late pregnancy. Manual therapy. 2014 Jun:19(3):190-6. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2014.01.004. Epub 2014 Jan 22 [PubMed PMID: 24508067]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHoffman MK, Bailit JL, Branch DW, Burkman RT, Van Veldhusien P, Lu L, Kominiarek MA, Hibbard JU, Landy HJ, Haberman S, Wilkins I, Gonzalez-Quintero VH, Gregory KD, Hatjis CG, Ramirez MM, Reddy UM, Troendle J, Zhang J, Consortium on Safe Labor. A comparison of obstetric maneuvers for the acute management of shoulder dystocia. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2011 Jun:117(6):1272-1278. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31821a12c9. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21555962]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSpain JE, Frey HA, Tuuli MG, Colvin R, Macones GA, Cahill AG. Neonatal morbidity associated with shoulder dystocia maneuvers. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2015 Mar:212(3):353.e1-5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.10.001. Epub 2014 Oct 5 [PubMed PMID: 25291256]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGilstrop M, Hoffman MK. An Update on the Acute Management of Shoulder Dystocia. Clinical obstetrics and gynecology. 2016 Dec:59(4):813-819 [PubMed PMID: 27681692]

Gardner R, Raemer DB. Simulation in obstetrics and gynecology. Obstetrics and gynecology clinics of North America. 2008 Mar:35(1):97-127, ix. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2007.12.008. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18319131]