Introduction

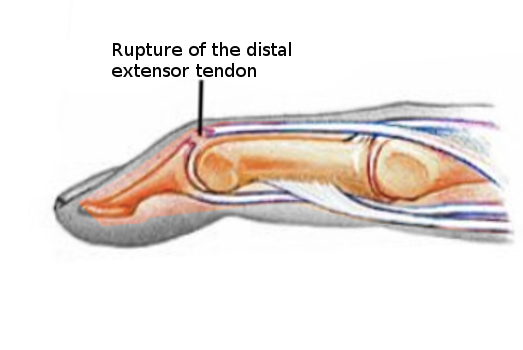

Mallet finger is the term usually applied to extensor avulsion fractures. However, this entity may also be caused by distal extensor tendon ruptures. Either one results in an inability to extend the DIP joint. Mallet finger injuries are named for the resulting flexion deformity of the fingertip, which resembles a mallet or hammer. Mallet finger injuries are caused by the disruption of the extensor mechanism of the phalanx at the level of the distal interphalangeal joint, usually due to a forced flexion at the distal interphalangeal joint. This injury results in the inability to extend the distal phalanx. A mallet fracture occurs when the extensor tendon also causes avulsion of the distal phalanx. There are three subtypes of mallet fractures based on the age of the patient and the percent of the articular surface of the distal phalanx involved. The treatment remains controversial. In general, it is guided by the amount of articular surface involved in the fracture.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The distal extensor tendon is ruptured. The rupture occurs when the distal phalanx of a finger is forced into flexion while being actively extended. The extrinsic extensor tendon originates in the forearm and courses over the metacarpophalangeal joint, has an indirect attachment to the proximal phalanx, and finally attaches to the distal phalanx. These tendons are responsible for the extension of the digits.[1] A mallet finger injury occurs when the extensor tendon is disrupted. In contrast, a mallet fracture occurs when the tendon injury causes an avulsion fracture of the distal phalanx.

Epidemiology

Mallet finger injuries usually occur in the workplace or during sports-related activities. There is a predisposition to these injuries during participation in ball sports, as the ball hits the fingertip of an extended finger. This compels the distal interphalangeal joint into a forced flexion position and thereby causes an extensor tendon disruption. Most often, such injuries involve the long finger, ring finger, or the little finger of the dominant hand. Frequently these injuries are seen in young to middle-aged men and occasionally in older women as well.[2]

Pathophysiology

Mallet finger injuries are usually caused by a traumatic event resulting in forced flexion of the extended fingertip. This causes a stretching or tearing of the extensor tendon. In severe injuries, this forced flexion can cause an avulsion of the tendon insertion on the distal phalanx and is described as a mallet fracture. Mallet finger injuries can also be caused by a laceration/abrasion, or more rarely, a forced hyperextension of the distal interphalangeal joint. Such an injury results in a fracture at the dorsal base of the distal phalanx. This disruption of extensor tendon function causes an unopposed flexion force on the finger and is accompanied by the inability to extend the digit. This injury results in the classic “mallet” appearance of the finger.

Classification System

Acute mallet finger deformities are defined as those occurring within four weeks of the injury, while chronic mallet finger deformities occur four weeks after the injury.

Doyle’s Classification of Mallet Finger Injuries[3]

- Closed injury, with or without small dorsal avulsion fracture

- Open injury (laceration)

- Open injury (deep abrasion involving skin and tendon)

- Mallet fracture

- Distal phalanx physeal injury in children

- Fracture fragment involving 20% to 50% of the articular surface

- Fracture fragment involving more than 50% of the articular surface

History and Physical

The diagnosis of mallet finger injuries is usually a clinical diagnosis. Patients typically present with the history of a forced flexion injury. However, this is not always the case. Patients usually complain of pain, flexion deformity, and/or difficulty using the affected digit.

The physical examination should begin with an inspection of the soft tissue. The examination should include a full assessment of the metacarpophalangeal joint and the proximal interphalangeal joint for full range of motion. When evaluating the distal interphalangeal joint, the fingertip will rest around 45 degrees of flexion with the inability to actively extend at the distal interphalangeal joint. There may or may not be swelling and tenderness over the distal interphalangeal joint, depending on the time-frame between injury and its presentation.

Evaluation

The diagnosis of a mallet finger is usually a clinical diagnosis. However, to distinguish between mallet finger injuries and mallet fractures, providers should obtain a three-view radiograph of the affected finger. Referring to these radiographs, one will either see a bony avulsion of the distal phalanx as in a mallet fracture, or the radiograph will be normal as in a mallet finger, the latter is due only to a ligamentous injury. The most valuable radiograph is the true lateral radiograph of the affected finger. This can help determine the size of the fracture fragment, displacement of the fracture fragment, and subluxation of the distal phalanx.

Treatment / Management

The treatment for mallet fractures remains controversial.[4][5][6] In general, closed mallet fractures involving less than one-third of the articular surface, without associated distal interphalangeal subluxation can be managed non-surgically with splinting as the mainstay of treatment.[7]However, the type of splint and duration of immobilization is controversial. Previously both the proximal and distal interphalangeal joints were immobilized to theoretically relax the extensor hood to promote healing of the terminal extensor tendon. However, studies on cadavers have shown that the proximal interphalangeal joint does not cause retraction of the proximal portion of the extensor tendon. Therefore, most authors advocate the immobilization of only the distal interphalangeal joint. Usually, the finger is splinted in full extension (typically, 0 to 10 degrees extension) at the DIP joint for 6 to 8 weeks. This is followed by part-time splinting for an additional 4 to 6 weeks.(A1)

Numerous types of splints have been used for mallet finger injuries. These include the stack splint, the perforated thermoplastic splint, or the aluminum-foam splint.[6] Regardless of the type of splint applied, the general principle of treatment involves full immobilization of the distal interphalangeal joint into full extension or slight hyperextension. Patients should remain in the splint continuously for 6 to 8 weeks, followed by two weeks of nighttime application only. Patients should begin progressive flexion exercises following six weeks of immobilization. The treatment should be restarted if the distal interphalangeal joint is accidentally flexed.(A1)

Surgical management is generally accepted for mallet fractures involving greater than one-third of the articular surface and for fractures with associated joint subluxation.[8] Many surgical techniques have also been proposed to manage mallet fractures. Similar to splinting, the general principle of surgical management of mallet fractures usually includes the placement of a Kirschner wire (K-wire) to immobilize the distal interphalangeal joint in full extension. Most surgeons suggest closed reduction and percutaneous pinning with K-wires as an alternative to open surgery to avoid complications such as pain, infection, skin irritation, and nail deformity.

Differential Diagnosis

- De Quervain tenosynovitis

- Distal interphalangeal joint dislocation

- Distal interphalangeal joint fracture/dislocation

- Distal interphalangeal volar plate avulsion fracture

- Finger amputation

- Fingertip laceration

- Jersey's finger

- Mallet Finger Fracture

- Metacarpophalangeal ulnar ligament rupture

- Nail avulsion

- Nailbed laceration

- Ring avulsion injury

- Subungual hematoma

- Swan-neck deformity

- Trigger finger

Pearls and Other Issues

The two major complications from mallet finger injuries and mallet fractures are residual extensor lag and swan neck deformities.[9] Extensor lag is the flexion deformity that can be noted on physical exam. Swan neck deformities are due to a disruption of the volar plate caused by the disrupted extensor tendon. This results in the distal interphalangeal joint becoming abnormally flexed and the proximal interphalangeal joint remaining in a hyperextended position. Either of these complications can occur following either nonsurgical or surgical management of mallet fractures.[10] Nurses and clinicians should assist in the education of the patient and family to get the best possible outcome. [Level 5]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Mallet finger injuries are best managed by an interprofessional team because the ideal treatment is not known. While conservative treatment with splints is widely used for mild injuries, the outcomes are unpredictable. Surgery is often done but again the results are not optimal. The nurse practitioner, emergency department physician, and primary care provider may need to refer these patients to a hand or plastic surgeon for further evaluation. Poorly treated mallet finger injuries are associated with high morbidity. Orthopedic or emergency department nurses should educate patients about splinting and communicate with the treating provider if there are issues. Irrespective of the type of treatment, patients should be encouraged to seek physical therapy. [Level 5]

Media

References

Colzani G, Tos P, Battiston B, Merolla G, Porcellini G, Artiaco S. Traumatic Extensor Tendon Injuries to the Hand: Clinical Anatomy, Biomechanics, and Surgical Procedure Review. Journal of hand and microsurgery. 2016 Apr:8(1):2-12. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1572534. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27616821]

STARK HH, BOYES JH, WILSON JN. Mallet finger. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 1962 Sep:44-A():1061-8 [PubMed PMID: 14039487]

Lin JS, Samora JB. Surgical and Nonsurgical Management of Mallet Finger: A Systematic Review. The Journal of hand surgery. 2018 Feb:43(2):146-163.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2017.10.004. Epub 2017 Nov 22 [PubMed PMID: 29174096]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGeyman JP, Fink K, Sullivan SD. Conservative versus surgical treatment of mallet finger: a pooled quantitative literature evaluation. The Journal of the American Board of Family Practice. 1998 Sep-Oct:11(5):382-90 [PubMed PMID: 9796768]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceWehbé MA, Schneider LH. Mallet fractures. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 1984 Jun:66(5):658-69 [PubMed PMID: 6725314]

Handoll HH, Vaghela MV. Interventions for treating mallet finger injuries. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2004:(3):CD004574 [PubMed PMID: 15266538]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSmit JM, Beets MR, Zeebregts CJ, Rood A, Welters CFM. Treatment options for mallet finger: a review. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2010 Nov:126(5):1624-1629. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181ef8ec8. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21042117]

Lamaris GA, Matthew MK. The Diagnosis and Management of Mallet Finger Injuries. Hand (New York, N.Y.). 2017 May:12(3):223-228. doi: 10.1177/1558944716642763. Epub 2016 Mar 30 [PubMed PMID: 28453357]

Stern PJ, Kastrup JJ. Complications and prognosis of treatment of mallet finger. The Journal of hand surgery. 1988 May:13(3):329-34 [PubMed PMID: 3379263]

Shankar NS, Goring CC. Mallet finger: long-term review of 100 cases. Journal of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh. 1992 Jun:37(3):196-8 [PubMed PMID: 1404050]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence