Introduction

Laryngomalacia ranks as the most prevalent cause of infant stridor. It is essential to make the diagnosis in early infancy as it may affect multiple aspects of growth and development. Stridor and noisy breathing are crucial symptoms to recognize as they may indicate varying degrees of respiratory compromise and may hint at the level of airway disruption. Thorough upper airway evaluation is necessary for children suspected of laryngomalacia for accurate diagnosis and proper treatment of the condition and any concurrent or underlying medical comorbidities. Laryngomalacia itself exists along a spectrum of severity. Watchful waiting may be all that is indicated for isolated, mild laryngomalacia. In contrast, severe laryngomalacia may increase the patient's work of breathing to such an extent that the majority of the caloric intake is expended on breathing, and the infant fails to thrive. Surgical intervention is necessary in these situations. This activity presents a general overview of the current diagnostic and management strategies for laryngomalacia in infants.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Multiple causal theories of laryngomalacia have been proposed, but the net result is the soft, immature cartilages of the infant larynx collapse upon inspiration, leading to noisy breathing (inspiratory stridor). Neurologic dysfunction is one of the leading theories, suggesting that altered laryngeal tone occurs by abnormal integration of the laryngeal nerves.[1] This concept supports a pathologic study showing increased supraglottic nerve diameter in patients with severe laryngomalacia.[2] Other theories, such as an imbalance of demand-supply upon infant inhalation, require further study.[3] While researchers have not found gastroesophageal reflux to be a causative factor for laryngomalacia, nearly 60% of infants have concomitant acid reflux disease.[4] Reflux is thought to cause irritation and edema of the upper airway, potentially worsening obstruction. Laryngomalacia is more likely to be symptomatic in infants with concurrent neuromuscular disease, with global hypotonia manifesting in the airway muscles and decreasing overall inspiratory strength.[5]

Epidemiology

The incidence of laryngomalacia in the general population is relatively unknown but has been estimated to be anywhere from 1 in 2000 to 1 in 3000.[6][7] This figure may be an underestimation, as mild laryngomalacia is often clinically followed by pediatricians and never diagnosed endoscopically. While previous evidence has suggested a male predominance, recently published literature suggests that it is equally common in females. Black and Hispanic infants may be at an increased risk compared to white infants.[7] Low birth weight has also been suggested to be a correlating factor, as have prematurity and neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission after birth.[7]

Pathophysiology

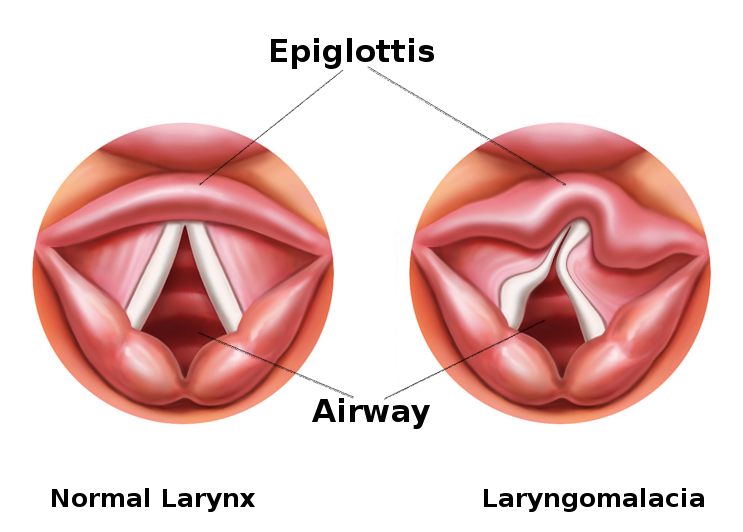

Laryngomalacia is a common congenital anomaly affecting the laryngeal structure in infants. The pathophysiology of laryngomalacia primarily involves an inherent structural weakness in the tissues of the larynx, particularly the supraglottic area. During inspiration, the normally rigid structures of the larynx may collapse inward, causing dynamic obstruction and resulting in the characteristic stridor observed in affected infants (see Image. Laryngomalacia). The precise mechanisms contributing to this collapse include softening or redundancy of the epiglottis, aryepiglottic folds, and other surrounding tissues. This structural vulnerability can lead to intermittent airway obstruction, especially during increased respiratory efforts. While laryngomalacia is often a self-limiting condition that improves with age as the laryngeal structures mature, severe cases may necessitate medical intervention to alleviate symptoms and ensure adequate respiratory function.

History and Physical

A full birth history is necessary, including any surgical procedures or intubations the patient has undergone and any stays in the NICU. Parents should provide information about breathing difficulties noted in the home, focusing on noisy breathing or episodes of apnea. Noisy breathing that seems to worsen with feeding or while supine is suspicious for laryngomalacia. The clinician should explore feeding and sleeping habits and note any weight loss, gastroesophageal reflux, recurrent pneumonia, or failure to thrive.

A complete physical examination of the infant should occur, with particular attention paid to the oral cavity, nose, and neck. Choanal patency should be assured, and piriform aperture stenosis should be ruled out. A full evaluation of the oral cavity for cleft lip or cleft palate, glossoptosis, Pierre-Robin sequence, or micrognathia are all essential, as they may contribute to breathing and feeding difficulties[8]. It is ideal to observe the patient feeding, both sitting and supine.

A careful examination of the neck to examine the presence and degree of any retractions when breathing and examination for masses or vascular lesions are also necessary. Chest examination includes auscultation and inspection for subcostal retractions. Particular attention should be paid to hemangiomas in a beard-like distribution, as these are associated with occult airway hemangioma.

Proper evaluation of the patient with suspected laryngomalacia requires an assessment of the supraglottic airway with flexible laryngoscopy in the awake infant. If the examiner notes severe symptoms, the infant should be taken to the operating room for a diagnostic laryngoscopy and bronchoscopy, with potential endoscopic intervention.[9]

Evaluation

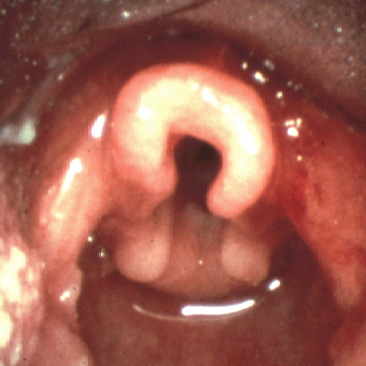

Flexible fiberoptic laryngoscopy is the mainstay in the diagnostic evaluation of infant stridor. It allows for visualization of the upper aerodigestive tract during respiration. An adequate examination gives the practitioner a complete view of the oropharynx, supraglottis, glottis, subglottis, and hypopharynx. Infants with laryngomalacia are often found to have shortened aryepiglottic folds that tether the epiglottis posteriorly, classically described as an omega-shaped epiglottis, and/or redundant arytenoid tissue that prolapses over the glottis (see Image. Laryngoscopic View of Laryngomalacia). Flexible fiberoptic laryngoscopy is currently the gold standard for diagnosing laryngomalacia due to the convenience and ability to directly assess the dynamic collapse of the supraglottic airway during awake respiration. It is important to note an approximately 5% incidence of concurrent structural lower airway pathology in infants with laryngomalacia, and flexible laryngoscopy alone will not reliably identify these lesions.[10]

Direct laryngoscopy and diagnostic bronchoscopy in the operating room give the practitioner a full evaluation of the upper aerodigestive tract to the level of the bronchi (mainstem bronchi if a rigid bronchoscopy is performed, segmental bronchi and beyond if a flexible bronchoscopy is performed). This procedure is an essential modality in patients with severe symptoms or patients with a concern for synchronous airway lesions. Direct laryngoscopy also allows for surgical intervention should it be warranted.

Radiologic studies of the swallowing mechanism with a speech therapist may be warranted if there is a concern for aspiration or a concomitant swallowing deficit in the child. A modified barium swallow study is preferred in infants with laryngomalacia, as aspiration may be silent and not detected clinically.[11]

A polysomnogram is useful to quantify the presence and degree of obstructive sleep apnea in a patient with laryngomalacia, especially in older children; this is sometimes described as sleep-exclusive laryngomalacia and has an incidence of approximately 4%.[12] Diagnosis is by drug-induced sleep endoscopy. These patients may benefit from surgical intervention with a supraglottoplasty to improve their apnea-hypopnea index (AHI).[12]

Airway fluoroscopy is not recommended in the evaluation of infant stridor as it has been found to have low sensitivity and requires increased exposure to ionizing radiation.[13]

Treatment / Management

Treatment of the majority of patients with laryngomalacia is conservative. In cases of mild or moderate stridor without feeding difficulties, observation is recommended after making a diagnosis. It is important to monitor for appropriate weight gain and the development of any severe symptoms outlined above.[14] Positional feeding and thickened feedings may help those infants with feeding difficulties.[14] Symptoms abate in the majority of patients by the age of 12 to 18 months without the need for surgical intervention.

Nearly 10% to 20% of infants with laryngomalacia will have severe symptoms. These patients often require surgical intervention.[15] A supraglottoplasty has become the initial treatment of choice for patients with severe symptoms. Multiple techniques for this procedure exist, including using a laser, cold steel, laryngeal microdebrider, or coblator. The most frequent reasons for surgical intervention are worsening airway symptoms and failure to thrive.[16] The supraglottoplasty procedure should be individualized to the particular patient’s anatomy. Still, it may consist of dividing shortened aryepiglottic folds, removing redundant arytenoid mucosa, performing an epiglottopexy, or a combination of these techniques. Care should be taken to avoid the interarytenoid mucosa, as glottic stenosis can result from scarring of this area and is a potentially devastating complication.(B3)

Supraglottoplasty has been shown to decrease the duration of symptoms of laryngomalacia significantly.[17] Patients generally tolerate the procedure well and are observed in the hospital postoperatively. Steroid administration during surgery and in the postoperative period decreases airway inflammation and is typically the recommended pharmaceutical therapy.[16]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for laryngomalacia should include the following etiologies of infant stridor:

- Unilateral or bilateral vocal fold paralysis

- Laryngeal papillomatosis

- Subglottic hemangioma

- Subglottic stenosis

- Tracheomalacia or bronchomalacia

- Vascular ring

- Foreign body aspiration

Unilateral vocal fold paralysis typically presents after a surgical procedure in the thoracic cavity or the neck, though it can be congenital as well. A hoarse cry is common, and these infants may have difficulties feeding. When bilateral vocal fold paralysis is present, infants typically have biphasic stridor and may require a tracheostomy if there is significant respiratory distress. Flexible fiberoptic laryngoscopy is used to diagnose these conditions.

Laryngeal papillomatosis may cause a hoarse cry with upper airway obstruction, which may present early in infancy, and diagnosis is by either flexible fiberoptic laryngoscopy or direct laryngoscopy and biopsy of the lesions.

Subglottic hemangiomas are a rare cause of stridor, typically expiratory. Hemangiomas in a beard-like distribution are clinically suggestive of subglottic extension or occult subglottic hemangioma. Confirmation is achievable with direct laryngoscopy and bronchoscopy.

Subglottic stenosis is usually congenital in patients in this age group, though it may also result from scarring of the subglottic region following prolonged intubation. Stridor may be heard but does not change with the infant's position.

Tracheomalacia and bronchomalacia may be present along with laryngomalacia. Expiratory airway sounds are generally present. Diagnosis is via bronchoscopy.

A vascular ring is a rare cause of airway obstruction. Feeding difficulties and stridor may be present. Diagnostic confirmation is with a contrasted computed tomography scan of the chest. This condition should be a suspected diagnosis with tracheomalacia seen on bronchoscopy or compression of the esophagus seen on an esophagram.

Foreign body aspiration is a possibility after finding an infant in respiratory distress after being unaccompanied or after ingesting food, causing a choking or coughing event. Diagnosis is suggested with chest x-ray findings and decreased unilateral breath sounds. Bronchoscopy should be performed to diagnose and retrieve the foreign body.

Prognosis

While resolution in the majority of patients is traditionally thought to occur by the age of 12 to 18 months, a recent article suggested there is limited evidence for this and that the age range at resolution may be much wider.[18] Conservative management with feeding upright, antireflux therapy, and close observation of respiratory symptoms are generally all that is necessary for the majority of infants.

The minority of patients who require surgical treatment with a supraglottoplasty have reliable outcomes, with some studies showing as high as 95% success rates.[19] Patients undergoing supraglottoplasty may require revision surgery for persistent symptoms; this is much more likely in patients younger than 2 months of age at the time of the first operation, patients with neurologic comorbidities such as hypotonia, seizures, cerebral palsy, and in patients with cardiac comorbidities such as septal defects, aortic or pulmonary stenosis, or pulmonary hypertension. Neurologic comorbidities have the highest rate of revision surgery at nearly 70%, with 60% of patients ultimately requiring tracheostomy due to persistent airway obstruction.[20]

Complications

Aspiration after supraglottoplasty is rare and has not been significantly correlated with the procedure, regardless of the operative technique. Factors associated with aspiration following surgery are neurologic comorbidities, revision surgery, and age younger than 18 months at the time of surgery.[21][22]

Nonsurgical treatment for laryngomalacia largely involves treating concomitant reflux disease. Most practitioners recommend treatment with a proton pump inhibitor (PPI). Reflux has been found to correlate with more severe forms of laryngomalacia. The use of PPI therapy has not, however, consistently shown to improve symptoms of laryngomalacia.[4]

Consultations

Depending on the initial physical examination, patients with laryngomalacia may need evaluations by subspecialists in neurology, gastroenterology, cardiology, developmental pediatrics, genetics, and speech pathology.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Education on the symptoms of laryngomalacia is of the utmost importance for parents, particularly the inconsistent correlation between noisy breathing and failure to thrive. Children can be quite noisy breathers but still grow and develop quite normally, and noisy breathing frequently remains even postsurgically.[23] Caregivers should be aware that treatment is mainly conservative, but that close follow-up is mandatory to monitor for worsening symptoms. Adherence to medication regimens should be encouraged. Parents should also be educated regarding the importance of compliance with thickened and positional feedings.

Pearls and Other Issues

Key facts to keep in mind regarding laryngomalacia are as follows:

- Most patients with laryngomalacia will outgrow this condition without any surgical intervention.

- Diagnosis of laryngomalacia is optimal with awake fiberoptic flexible laryngoscopy.

- Severe symptoms of laryngomalacia, including recurrent cyanosis or respiratory distress, apnea, and failure to thrive, require further workup with direct laryngoscopy and bronchoscopy to rule out other synchronous airway abnormalities.

- Surgery is generally only an indication in patients with severe laryngomalacia with significant breathing difficulties or failure to thrive.

- Supraglottoplasty is the surgical method of choice and is generally well-tolerated.

- Patients with neurologic comorbidities, cardiac comorbidities, and those younger than 2 months of age are more likely to require revision surgery for relief of upper airway obstruction.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Laryngomalacia is a diagnosis that is critical to make in infancy. Effective patient-centered care relies on an interprofessional approach involving various healthcare professionals. Physicians must hone skills in accurate diagnosis and surgical intervention when necessary. Advanced care practitioners contribute by implementing evidence-based strategies and offering comprehensive care. Nurses play a crucial role in patient monitoring and education. Pharmacists contribute by managing medications and potential interactions, emphasizing patient safety.

A thorough history and physical examination may not completely suggest a diagnosis, and referral to an otolaryngologist for flexible fiberoptic laryngoscopy is a recommended practice. It is crucial that communication between the parents, primary clinician, and specialists continually take place, as each will provide valuable subjective and objective information. Because most patients are observed clinically once diagnosed, history from multiple sources provides the clearest picture of the patient's clinical course. In patients with worsening or severe symptoms, prompt evaluation of the airway may lead to earlier treatment of airway obstruction. By communicating frequently and recognizing worsening clinical courses, a collaborative approach between all clinicians may improve outcomes and lead to the early diagnosis of more severe airway issues.

Nurses in the NICU and parents at home will often be the first to notice issues suggestive of laryngomalacia. Nurses must report these symptoms immediately to the clinician. Specialists will regularly consult on such cases, and they can collaborate with both the neonatal nursing staff and the primary clinician. Nurses may also be the first point of contact for parents with a newborn as they come in for vaccinations or other postnatal appointments. It is crucial that the nurses play a part in the assessment of the baby and assist in obtaining the history of the infant so that they can alert the team regarding any abnormalities so diagnostic procedures can take place if necessary.

Interprofessional communication becomes imperative, with open dialogue fostering shared understanding. Responsibility lies in each professional's commitment to staying informed and engaged, promoting optimal outcomes. Collaborative care coordination ensures a seamless patient journey, enhancing team performance and overall quality of care for infants with laryngomalacia.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Thompson DM. Abnormal sensorimotor integrative function of the larynx in congenital laryngomalacia: a new theory of etiology. The Laryngoscope. 2007 Jun:117(6 Pt 2 Suppl 114):1-33 [PubMed PMID: 17513991]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMunson PD, Saad AG, El-Jamal SM, Dai Y, Bower CM, Richter GT. Submucosal nerve hypertrophy in congenital laryngomalacia. The Laryngoscope. 2011 Mar:121(3):627-9. doi: 10.1002/lary.21360. Epub 2011 Jan 13 [PubMed PMID: 21344444]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRathi A, Rathi S. Relative imbalance as etiology of laryngomalacia - A new theory. Medical hypotheses. 2017 Jan:98():38-41. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2016.11.004. Epub 2016 Nov 23 [PubMed PMID: 28012601]

Hartl TT, Chadha NK. A systematic review of laryngomalacia and acid reflux. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2012 Oct:147(4):619-26 [PubMed PMID: 22745201]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLiu Y, Wu W, Huang Q. Endoscopic management of pediatric extubation failure in the intensive care unit. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2020 Dec:139():110465. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2020.110465. Epub 2020 Oct 23 [PubMed PMID: 33120102]

Boogaard R, Huijsmans SH, Pijnenburg MW, Tiddens HA, de Jongste JC, Merkus PJ. Tracheomalacia and bronchomalacia in children: incidence and patient characteristics. Chest. 2005 Nov:128(5):3391-7 [PubMed PMID: 16304290]

Edmondson NE, Bent JP 3rd, Chan C. Laryngomalacia: the role of gender and ethnicity. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2011 Dec:75(12):1562-4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2011.09.008. Epub 2011 Sep 28 [PubMed PMID: 21955525]

Chen J, Xu H, Li X. Von Mises stress peak (VMSP) and laryngomalacia severity score (LSS) are extremely useful in the selection of treatment for laryngomalacia. European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology : official journal of the European Federation of Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Societies (EUFOS) : affiliated with the German Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology - Head and Neck Surgery. 2023 Jul:280(7):3287-3293. doi: 10.1007/s00405-023-07866-5. Epub 2023 Feb 9 [PubMed PMID: 36757513]

Ke LQ, Shi MJ, Zhang FZ, Wu HJ, Wu L, Tang LF. The clinical application of flexible bronchoscopy in a neonatal intensive care unit. Frontiers in pediatrics. 2022:10():946579. doi: 10.3389/fped.2022.946579. Epub 2022 Oct 10 [PubMed PMID: 36299699]

Vijayasekaran D, Balasubramanian S, Sivabalan S, Vindhiya K. Clinical Characteristics and Associated Congenital Lesions with Tracheomalacia in Infants. Indian pediatrics. 2018 Oct 15:55(10):883-884 [PubMed PMID: 30426955]

Gasparin M, Schweiger C, Manica D, Maciel AC, Kuhl G, Levy DS, Marostica PJ. Accuracy of clinical swallowing evaluation for diagnosis of dysphagia in children with laryngomalacia or glossoptosis. Pediatric pulmonology. 2017 Jan:52(1):41-47. doi: 10.1002/ppul.23484. Epub 2016 May 26 [PubMed PMID: 27228428]

Camacho M, Dunn B, Torre C, Sasaki J, Gonzales R, Liu SY, Chan DK, Certal V, Cable BB. Supraglottoplasty for laryngomalacia with obstructive sleep apnea: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Laryngoscope. 2016 May:126(5):1246-55. doi: 10.1002/lary.25827. Epub 2015 Dec 22 [PubMed PMID: 26691675]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHuntley C, Carr MM. Evaluation of the effectiveness of airway fluoroscopy in diagnosing patients with laryngomalacia. The Laryngoscope. 2010 Jul:120(7):1430-4. doi: 10.1002/lary.20909. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20578105]

Thorne MC, Garetz SL. Laryngomalacia: Review and Summary of Current Clinical Practice in 2015. Paediatric respiratory reviews. 2016 Jan:17():3-8. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2015.02.002. Epub 2015 Feb 28 [PubMed PMID: 25802018]

Thompson DM. Laryngomalacia: factors that influence disease severity and outcomes of management. Current opinion in otolaryngology & head and neck surgery. 2010 Dec:18(6):564-70. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0b013e3283405e48. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20962644]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRamprasad VH, Ryan MA, Farjat AE, Eapen RJ, Raynor EM. Practice patterns in supraglottoplasty and perioperative care. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2016 Jul:86():118-23. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2016.04.039. Epub 2016 May 3 [PubMed PMID: 27260594]

van der Heijden M, Dikkers FG, Halmos GB. Treatment outcome of supraglottoplasty vs. wait-and-see policy in patients with laryngomalacia. European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology : official journal of the European Federation of Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Societies (EUFOS) : affiliated with the German Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology - Head and Neck Surgery. 2016 Jun:273(6):1507-13. doi: 10.1007/s00405-016-3943-3. Epub 2016 Feb 29 [PubMed PMID: 26924742]

Isaac A, Zhang H, Soon SR, Campbell S, El-Hakim H. A systematic review of the evidence on spontaneous resolution of laryngomalacia and its symptoms. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2016 Apr:83():78-83. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2016.01.028. Epub 2016 Feb 2 [PubMed PMID: 26968058]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSedaghat S, Fredes F, Tapia M. Supraglottoplasty for laryngomalacia: The experience from Concepcion, Chile. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2017 Dec:103():113-116. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2017.10.012. Epub 2017 Oct 7 [PubMed PMID: 29224749]

Hoff SR, Schroeder JW Jr, Rastatter JC, Holinger LD. Supraglottoplasty outcomes in relation to age and comorbid conditions. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2010 Mar:74(3):245-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2009.11.012. Epub 2009 Dec 21 [PubMed PMID: 20022388]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRastatter JC, Schroeder JW, Hoff SR, Holinger LD. Aspiration before and after Supraglottoplasty regardless of Technique. International journal of otolaryngology. 2010:2010():912814. doi: 10.1155/2010/912814. Epub 2010 Nov 21 [PubMed PMID: 21113300]

Anderson de Moreno LC, Burgin SJ, Matt BH. The incidence of postoperative aspiration among children undergoing supraglottoplasty for laryngomalacia. Ear, nose, & throat journal. 2015 Aug:94(8):320-8 [PubMed PMID: 26322450]

Cialente F, Meucci D, Tropiano ML, Salvati A, Torsello M, Savignoni F, Landolfo F, Dotta A, Trozzi M. Changes in Breathing Patterns after Surgery in Severe Laryngomalacia. Children (Basel, Switzerland). 2021 Dec 3:8(12):. doi: 10.3390/children8121120. Epub 2021 Dec 3 [PubMed PMID: 34943316]