Introduction

Intraocular hemorrhage is a critical condition characterized by bleeding within the eye, which can occur in any vascularized structure. Bleeding can affect various areas, including the anterior chamber, vitreous cavity, retina, choroid, suprachoroidal space, and optic disc. The condition can arise from trauma, systemic vascular diseases such as diabetes and hypertension, retinal vein occlusion, neovascularization, or, in rare cases, spontaneously. Intraocular hemorrhage is typically classified based on the specific location and extent of the hemorrhage.[1]

Hyphema

Hyphema refers to bleeding from the iris, ciliary body, trabecular meshwork, and associated vasculature into the anterior chamber, which is bordered by the cornea anteriorly, the iridocorneal angles laterally, and the lens posteriorly.[2] Microhyphema denotes a minimal amount of blood in the anterior chamber, detectable only through microscopic examination.

Vitreous Hemorrhage

Vitreous hemorrhage refers to bleeding within the anterior chamber of the eye. This condition can be further classified based on the specific location and characteristics of the bleeding.

- Intragel hemorrhage: This refers to the accumulation of blood within the vitreous body, bordered anteriorly by the anterior hyaloid membrane, laterally by the nonpigmented ciliary epithelium, and posteriorly by the posterior hyaloid membrane. The blood settles inferiorly and clots easily. As the red blood cells degenerate, the color of the vitreous hemorrhage transitions from bright red to yellow.[3]

- Preretinal hemorrhage: This can be subdivided into 2 categories, as mentioned below.

- Subhyaloid hemorrhage: This type of bleeding occurs between the internal limiting membrane (ILM) and the posterior subhyaloid membrane, often presenting in a boat-shaped configuration. If the posterior hyaloid membrane remains intact, the hemorrhage is immobile. However, if the posterior hyaloid is detached, the blood may shift with eye movement. Subhyaloid hemorrhages are commonly observed in proliferative diabetic retinopathy.

- Sub-ILM hemorrhage: In this type, bleeding occurs between the ILM and the nerve fiber layer of the retina, also exhibiting a boat-shaped configuration with a horizontal upper border. The affected area remains immobile. Sub-ILM hemorrhage is frequently associated with conditions such as Valsalva retinopathy, Terson syndrome, and retinal microaneurysms.

- Hemorrhage in the Berger space, Cloquet canal, or canal of Petit is also classified as vitreous hemorrhage.[4]

Suprachoroidal Hemorrhage

Suprachoroidal hemorrhage occurs when long or short ciliary arteries rupture, causing bleeding into the suprachoroidal space between the choroid and sclera. This type of bleeding typically occurs intraoperatively or postoperatively, following trauma, and, very rarely, spontaneously. Intraoperative hemorrhage is referred to as expulsive suprachoroidal hemorrhage, while postoperative hemorrhage is known as delayed suprachoroidal hemorrhage.[5]

Retinal Hemorrhage

Retinal hemorrhage is a significant marker indicating a local or systemic vascular abnormality that requires thorough investigation. Retinal hemorrhages can occur at various locations, including:

- Flame-shaped hemorrhages, which are located in the nerve fiber layer.

- Dot and blot hemorrhages, which are located in the outer plexiform layer-inner nuclear layer complex.

- Subhyaloid hemorrhages, which occur between the internal limiting and posterior hyaloid membranes, presenting a boat-shaped configuration.

- Subretinal pigment epithelium hemorrhages, which are located between the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and the Bruch membrane.

- Subretinal hemorrhages, which are located between the RPE and the photoreceptor layer. (Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Retinal Hemorrhage," for more information.)

Disc Hemorrhage

Disc hemorrhage, also known as Drance hemorrhage, is characterized by a linear hemorrhage that is perpendicular to the optic disc. The most common locations for disc hemorrhages are at the superotemporal or inferotemporal margins.

Submacular Hemorrhage

Submacular hemorrhage occurs due to abnormalities in the choroidal and retinal vessels, often resulting from a choroidal neovascular membrane associated with age-related macular degeneration (ARMD). This type of hemorrhage directly affects the quality of vision.[6]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Understanding the etiology of intraocular hemorrhage is essential for accurate diagnosis and effective management. Intraocular bleeding can be classified by its underlying causes, distinguishing between systemic and ocular origins.

Systemic Causes of Intraocular Hemorrhage

- Diabetes mellitus

- Hypertension

- Trauma

- Blood dyscrasias

- Bleeding and coagulation disorders

- Shaken baby syndrome

- Purtscher retinopathy

- Terson syndrome

- Head injury

- Valsalva maneuver

- Drug-induced (eg, intravenous streptokinase injection and other anticoagulants)

- Anemia

- Hemoglobinopathy [7]

Ocular Causes of Intraocular Hemorrhage

- Ocular trauma

- Proliferative diabetic retinopathy

- Arterial microaneurysm

- Retinal tear with rupture of bridging vessels

- Venous occlusive disease

- Severe ocular hypotony

- Any intraocular surgical intervention [1]

The etiology of intraocular hemorrhage can also be classified according to the type and specific anatomical location of the bleeding. Understanding the relationship between the bleeding site and its underlying causes is crucial for developing targeted treatment strategies.

Hyphema

Hyphema can result from traumatic injuries (blunt or penetrating), postsurgical complications, or bleeding from iris neovascularization, most commonly associated with proliferative diabetic retinopathy, coagulation disorders, and herpetic keratouveitis. Common examples include:

- Posttraumatic hyphema: This occurs after blunt or penetrating trauma due to direct or indirect injury to the anterior segment vasculature.

- Postsurgical hyphema: This develops after intraocular surgical procedures.

- Spontaneous hyphema: The causes of this condition are listed below.

- Local causes include rubeosis iridis (eg, proliferative diabetic retinopathy and ocular ischemia), iris tumors (eg, iris melanoma and retinoblastoma), uveitis, juvenile xanthogranuloma, and herpetic keratouveitis (candy-cane hypopyon).

- Systemic causes include leukemia, von Willebrand disease, and hemophilia.

Patients on antiplatelet and/or thrombolytic medications, such as aspirin and warfarin, are also at increased risk.[8]

Vitreous Hemorrhage

Vitreous hemorrhage can result from various etiologies, as mentioned below.

- Systemic or local predisposing conditions, which alter the retinal vascular wall, blood viscosity, and composition.

- Local traction on the vascular sheath leads to breakthrough bleeding.

- Retinal ischemia promotes the formation of fragile neovessels that lack pericytes, making them prone to rupture and resulting in vitreous hemorrhage.

- In rare circumstances, vitreous hemorrhage can occur spontaneously.[9]

Specific causes of vitreous hemorrhage include:

- Trauma

- Proliferative diabetic retinopathy

- Retinal venous occlusion

- Vasculitis (eg, Eales disease)

- Retinopathy of prematurity

- Wet ARMD

- Idiopathic polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy (IPCV)

- Valsalva retinopathy

- Sickle cell retinopathy

- Ruptured retinal arterial microaneurysms

- Intraocular surgery complications

- Systemic hematological disorders such as anemia, leukemia, thrombocytopenia, hemophilia, thalassemia, and other bleeding and coagulation disorders

- Shaken baby syndrome

- Intraocular tumors

- Terson syndrome

Suprachoroidal Hemorrhage

Suprachoroidal hemorrhage is associated with various ocular predispositions, including a history of glaucoma, aphakia, elevated intraocular pressure before surgery, and prior ocular interventions or trauma. Additional risk factors include high myopia, prolonged or complicated eye surgeries, posterior capsule rupture with vitreous loss, sudden severe hypotony, and Valsalva-like maneuvers (eg, excessive vomiting, coughing, or sneezing) during or shortly after surgery.[9]

Retinal and Macular Hemorrhages

Retinal and macular hemorrhages can occur in various pathological conditions, including diabetic retinopathy, hypertensive retinopathy, retinal vein occlusion, wet ARMD, IPCV, macroaneurysms, Valsalva retinopathy, sickle cell retinopathy, Terson syndrome, Purtscher retinopathy, shaken baby syndrome, leukemic retinopathy, and bacterial endocarditis.[10]

Optic Disc Hemorrhage

Optic disc hemorrhage remains enigmatic regarding its exact cause. The etiology of disc hemorrhage has been debated for decades. Optic disc hemorrhage is believed to result from mechanical stretching near the lamina cribrosa or ischemic microinfarction at the optic disc head, which can arise from both glaucomatous and non-glaucomatous factors.[11]

Epidemiology

Traumatic eye injuries can exert shearing forces on normal blood vessels, leading to their rupture and subsequent ocular bleeding. Such injuries can occur at any age and affect individuals of all genders. However, they are more prevalent in young males, likely due to outdoor occupational activities and work with heavy machinery. In children, traumatic injuries are more common during the summer season, attributed to increased outdoor activities during school vacations. The incidence of traumatic hyphema is approximately 12 injuries per 100,000 people, with males being affected 3 to 5 times more than females.[12] Notably, up to 70% of traumatic hyphemas occur in children, particularly in the age group of 10 to 20.[12]

In a study by Butner et al, the distribution of vitreous hemorrhage cases was 34.1% were associated with diabetic retinopathy, 22.4% with retinal breaks without detachment, 14.9% with rhegmatogenous retinal detachment, and 13% with retinal vein occlusion.[13] The remaining 16% of cases were attributed to other causes, including posterior vitreous detachment, retinal vasculitis, sickle cell retinopathy ARMD, tumors, retinopathy of prematurity, leukemias, acute retinal necrosis, HIV-related retinopathy, and, rarely, uveitis.[13]

The incidence and prevalence of intraocular hemorrhage are directly correlated with the prevalence of predisposing factors that lead to bleeding.[14] In a study by Obuchowska et al, the incidence of suprachoroidal hemorrhage after all ocular surgeries was 0.29%.[15] Additionally, Al-Hitq et al revealed that the incidence of submacular hemorrhage was 5.4 per million per annum, with 52% of their patients having a history of ARMD.[16] The incidence of shaken baby syndrome is reported to be between 15 and 30 per 100,000 children aged 1 and younger.[17][18]

Pathophysiology

The 3 main pathophysiological mechanisms of intraocular hemorrhage include bleeding from normal vessels (secondary to trauma), bleeding from abnormal vessels (associated with systemic hypertension and uveitis), and bleeding from newly formed immature vessels (which can arise from fibrovascular membranes and neoplasia).[3] To fully understand intraocular bleeding, it is crucial to explore its pathophysiology in relation to the type or location of the hemorrhage. Different types of hemorrhages—such as those occurring in the vitreous body, retina, or anterior chamber—exhibit distinct pathophysiological mechanisms.

Hyphema

- In blunt trauma, coup-countercoup forces apply shearing stress to the blood vessels of the iris, ciliary body, and trabecular meshwork, resulting in vessel rupture and bleeding into the anterior chamber.

- In cases of penetrating trauma, direct injury to ocular structures and their vasculature can also lead to intraocular bleeding. Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Blunt Eye Trauma," for more information.

- Ocular surgeries that pose a risk of inflammation and infection increase the likelihood of hyphema. Iatrogenic injury to the iris, trabecular meshwork, or ciliary body may result in intraoperative or early postoperative bleeding.

- An anterior chamber intraocular lens (IOL) can cause chronic iris irritation, increasing the risk of intraocular bleeding. Scleral-fixated IOL implantation may injure the ciliary body or the posterior surface of the iris, leading to intraocular bleeding. Similarly, iris claw lenses can rupture iris vessels, resulting in intraoperative or early postoperative bleeding. Procedures such as Nd-YAG laser iridotomy or posterior capsulotomy are also associated with a risk of hyphema.

- Uveitis–glaucoma–hyphema or UGH syndrome was first described by a scientist named Ellingson in 1978. UGH syndrome is characterized by a triad of uveitis, glaucoma, and hyphema, typically seen in patients with IOL implantation, most commonly with an anterior chamber IOL. The syndrome arises due to continuous chafing of the iris by the IOL, resulting in chronic inflammation, iris transillumination defects, pigment dispersion, and hyphema, which obstructs the trabecular meshwork and leads to glaucoma.

- In spontaneous hyphema, bleeding may occur from fragile normal vessels secondary to a local or systemic cause or from neovessels. Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Uveitis Glaucoma Hyphema Syndrome," for more information.

Vitreous Hemorrhage

- Bleeding within the vitreous cavity differs significantly from hemorrhages in other parts of the body.[4]

- Vitreous hemorrhage typically settles inferiorly and clots rapidly.

- The initial polymorphonuclear lymphocyte response is minimal, resulting in only a mild inflammatory reaction, which helps limit inflammatory damage to the adnexal structures.

- A study by Sanders et al reported that blood from the vitreous cavity clears at a rate of 1% daily.[19]

- As the red blood cells degenerate, the color of the hemorrhage changes from red to yellow.

Suprachoroidal Hemorrhage

- The 2 primary hypotheses that explain the pathophysiology of suprachoroidal hemorrhage are mentioned below.

- The first hypothesis suggests that sudden hypotony causes significant choroidal effusion, which stretches the walls of the long or short ciliary arteries, leading to rupture and bleeding into the suprachoroidal space.[20][21]

- The second hypothesis posits that in patients with preexisting damage or weakened posterior ciliary arteries, sudden hypotony increases the risk of arterial rupture and subsequent bleeding into the suprachoroidal space.[22][23]

Retinal Hemorrhage

- Retinal hemorrhages are classified based on the site of bleeding—sub-RPE hemorrhage (between the RPE and Bruch membrane), subretinal hemorrhage (between the RPE and neurosensory retina), intraretinal hemorrhage (dot and blot hemorrhages), and retinal nerve fiber layer hemorrhage (flame-shaped hemorrhage, splinter hemorrhage, and Roth spots).

- Sub-ILM hemorrhage is considered a part of the pre-retinal type of vitreous hemorrhage.

- Hemorrhages in the various retinal layers are typically caused by systemic predisposing factors, sudden shearing stress on the vessels, or, in rare cases, occur spontaneously.

Optic Disc Hemorrhage

- The pathophysiology of optic disc hemorrhage remains debated, with 2 primary hypotheses proposed—the mechanical theory and the vascular theory.

- The mechanical theory suggests that neurodegenerative changes, secondary to connective tissue remodeling and glial tissue formation, create a shearing effect on the vessels over the disc, leading to hemorrhage.

- The vascular theory, in contrast, posits that ischemia from optic disc infarction or disruption of the blood-retinal barrier results in hemorrhage at the optic disc.[24]

- In cases of disc hemorrhage, glaucoma must always be ruled out. When disc hemorrhage occurs in a patient with a known diagnosis of glaucoma, it serves as a marker for disease progression.[25][26]

Shaken Baby Syndrome

Shaken baby syndrome results from child abuse, where the child experiences severe trauma, leading to subdural and retinal hemorrhages.[27]

Histopathology

Histopathology is crucial in understanding the cellular and tissue-level manifestations of intraocular hemorrhage. Upon examining tissue samples from cases of intraocular hemorrhage, histopathologists may observe a range of changes that vary based on the underlying cause and the duration of the hemorrhage.

Hemosiderin deposition: A key finding in chronic intraocular hemorrhage is the presence of hemosiderin-laden macrophages. Hemosiderin is an iron-storage complex formed following the breakdown of red blood cells. In cases of chronic or recurrent hemorrhage, these deposits can lead to hemosiderosis, which may contribute to further tissue damage, particularly in the retina.[28]

Fibrosis: Repeated hemorrhages or long-standing intraocular blood can lead to fibrous tissue proliferation within the vitreous or retina of the eye. This process can result in tractional retinal detachment, a severe complication associated with significant vision loss.[29]

Retinal damage: The severity and duration of hemorrhage can lead to varying degrees of retinal damage, including atrophy, scarring, or necrosis of retinal layers. The location of the hemorrhage—preretinal, intraretinal, or subretinal—can result in distinct damage patterns, which histopathological examination can help elucidate.[30]

Neovascularization: Chronic hemorrhage, especially in the setting of ischemic retinal diseases (eg, diabetic retinopathy), can promote the growth of abnormal new blood vessels. Histopathological examination may reveal these fragile neovessels, which are susceptible to rebleeding and contribute to the cycle of hemorrhage.[29]

Vascular abnormalities: Histopathological examination can reveal underlying vascular abnormalities that may contribute to hemorrhage. In conditions such as retinal vein occlusion or hypertensive retinopathy, findings may include vessel wall thickening, arteriolar narrowing, or fibrinoid necrosis.[31]

Inflammatory cells: In cases of intraocular hemorrhage associated with uveitis or other inflammatory conditions, histopathological examination may show a mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate. This infiltrate can include lymphocytes, plasma cells, and macrophages, indicating an underlying inflammatory etiology.[32]

Tumor identification: In rare cases, intraocular hemorrhage may be associated with intraocular tumors, such as retinoblastoma in children or choroidal melanoma in adults. Histopathological analysis is essential for diagnosing these conditions by identifying malignant cells and offering insights into tumor type, grade, and metastatic potential. Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Retinoblastoma," for more information.

Histopathological examination of tissues in intraocular hemorrhage provides invaluable insights into the underlying causes, the extent of damage, and potential complications, which can guide management and prognosis. By analyzing cellular changes and vascular integrity, histopathological examination can identify underlying conditions such as retinal tears, neovascularization, or inflammatory processes. These findings aid in tailoring treatment strategies, predicting visual outcomes, and informing decisions about medical or surgical interventions.

History and Physical

Clinicians should gather a comprehensive history regarding the condition's origin, duration, and progression. Detailed information about any associated traumatic injuries, such as motor vehicle crashes, physical assaults, or chest compressions, must be included.[33] A thorough systemic medical history should address diabetes, hypertension, increased intracranial pressure, metabolic disorders, bleeding and coagulation disorders, and kidney and cardiac disorders. A thorough medication history should be obtained from patients. In individuals with macular hemorrhage, it is important to inquire about additional findings such as central scotoma, metamorphopsia, micropsia, and any loss of color or contrast sensitivity. A thorough slit-lamp examination will help assess the bleed's size, extent, location, severity, and associated complications.[34]

Hyphema can be classified into 4 grades depending on its height from the inferior limbus during slit-lamp examination, as mentioned below. Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Hyphema," for more information.

- Grade 0: Microhyphema (red blood cells scattered in the anterior chamber).

- Grade I: Hyphema involving less than 1/3 of the anterior chamber.

- Grade II: Hyphema involving 1/3 to 1/2 of the anterior chamber.

- Grade III: Hyphema involving more than 1/2 but less than the total anterior chamber.

- Grade IV: Total hyphema (the anterior chamber is completely filled with fresh blood).

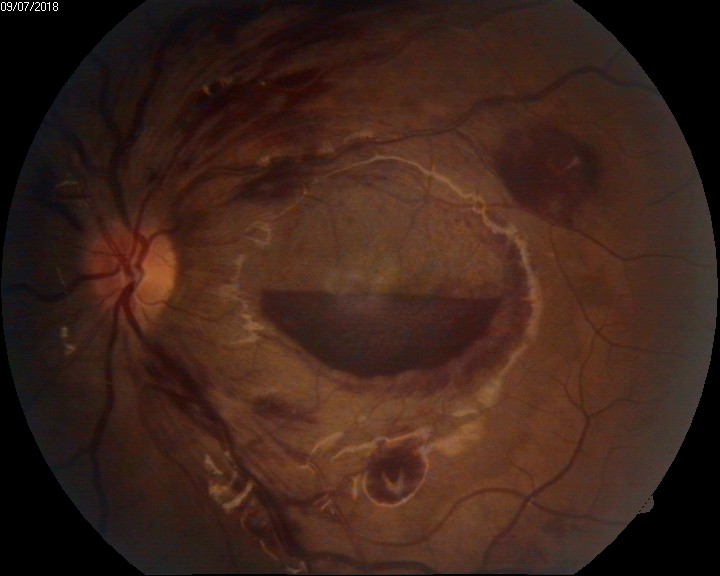

Clinicians must monitor intraocular pressure regularly. Gonioscopy is essential for patients with hyphema, iris and angle neovascularization, and traumatic ocular injuries to rule out angle recession. Pupillary reflexes should be assessed after dilating the pupil. A dilated fundus examination is conducted to check for vitreous hemorrhage, and a detailed retinal examination is performed to determine the cause of the bleeding (see Image. Intraocular Hemorrhage on Funduscopy). Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Traumatic Glaucoma," for more information.

In conditions where visibility is compromised, B-scan ultrasonography is conducted to assess for additional conditions such as a dislocated lens or IOL, foreign bodies, vitreous hemorrhage, retinal detachment, optic nerve avulsion, choroidal detachment, and suprachoroidal hemorrhage. In cases of traumatic injuries, a computed tomography (CT) scan of the orbit is necessary to rule out orbital fractures, the presence of an intraocular foreign body (IOFB), and any associated brain injuries. Ocular investigations include optical coherence tomography (OCT), OCT-angiography (OCT-A), fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA), and indocyanine green (ICG) angiography. Fundus photography is performed to locate and document the cause of vitreous, retinal, and macular hemorrhages.[35]

Suprachoroidal hemorrhage primarily occurs either intraoperatively or postoperatively. In cataract surgery, hemorrhage mainly occurs intraoperatively, whereas in glaucoma surgery, hemorrhage mainly occurs postoperatively.[20] Symptoms of suprachoroidal hemorrhage include severe pain, nausea and vomiting, and a decrease in vision postoperatively. Signs suggestive of this condition include the loss of the red reflex, a sudden increase in intraocular pressure, anterior chamber swelling, bulging of the posterior capsule, and expulsion of intraocular contents. Additionally, iris prolapse from the wound may occur, along with the anterior expulsion of the iris, lens, retina, and choroid, as well as choroidal elevation.

Evaluation

Intraocular hemorrhage, or bleeding within the eye, can occur in different compartments and is classified based on its location. Proper evaluation of intraocular hemorrhage involves identifying the specific type, as this determines the underlying cause and the approach to management. The primary types include hyphema, vitreous hemorrhage, and subretinal hemorrhage—each presenting with distinctive clinical features and implications. A comprehensive assessment of the type and extent of the hemorrhage is crucial for selecting the appropriate treatment and predicting visual outcomes.

Hyphema

- The diagnosis of hyphema is confirmed by a slit-lamp examination.

- In cases of traumatic hyphema, an open globe injury must be ruled out. A CT scan is recommended to assess for orbital fractures or the presence of an IOFB. Ultrasonography should be performed to rule out vitreous hemorrhage, IOFB, lens dislocation, and retinal detachment.

- For patients with spontaneous hyphema, it is important to evaluate for bleeding and coagulation disorders, hypertension, and any history of anticoagulant use.[36]

Vitreous Hemorrhage

- In patients presenting with vitreous hemorrhage, it is essential to assess systemic metabolic stability initially.

- Common causes such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, trauma, chest compression, elevated intracranial pressure, systemic autoimmune vasculitis, history of tuberculosis, bleeding or coagulation disorders, and anticoagulant use should be thoroughly investigated.

- Routine evaluations should include a complete blood count (CBC), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), bleeding time, serum homocysteine levels, prothrombin time (PT) with international normalized ratio (INR), peripheral blood smear, Mantoux test, chest x-ray, and CT scan.[3]

- If the retina is hazily visible through the bleed, indirect ophthalmoscopy and slit-lamp biomicroscopic examination using a 90D or 78D lens should be conducted to thoroughly investigate the cause of bleeding and assess posterior segment involvement.

- If macular pathology such as wet age-related macular degeneration ARMD, IPCV, choroidal rupture at the macula, ruptured microaneurysm, retinal venous occlusion, or diabetic macular edema is suspected on examination, OCT and OCT-A should be performed to determine the underlying cause. Differentiating between sub-ILM and subhyaloid hemorrhages is beneficial.

- If the fundus is visible, FFA should be used to identify the cause, extent, and location of retinal ischemia. ICG angiography is recommended if choroidal involvement is suspected.

- B-scan ultrasonography should be performed in cases with limited retina visibility to diagnose vitreous hemorrhage and assess for associated findings such as retinal detachment, posterior vitreous detachment, lens dislocation, IOFB, or traction at the posterior pole. This imaging modality can also help differentiate subhyaloid hemorrhage from true vitreous hemorrhage. Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Auxiliary Lenses for Slit-Lamp Examination of the Retina," for more information.

Suprachoroidal Hemorrhage

- Suprachoroidal hemorrhage is typically diagnosed based on clinical presentation.

- In cases where distorted intraocular anatomy prevents adequate evaluation of the posterior segment, B-scan ultrasonography is used to confirm the diagnosis.

- B-scan ultrasonography can also localize the site and extent of the bleed, aiding in surgical planning for drainage.

- Ultrasonography can also help rule out associated conditions such as retinal detachment or vitreous hemorrhage.[35]

- Postsurgical follow-up is essential for monitoring eye condition and recovery.

- An amplitude scan (or A-scan) typically shows a high reflective spike at the wall of the suprachoroidal hemorrhage, followed by a lower reflective spike indicating clotted blood in the suprachoroidal space.

- CT scans and magnetic resonance imaging (MRIs) can also help localize the site and extent of the hemorrhage.

- FFA, ICG angiography, and OCT may help rule out the causes of vision loss; however, they are only effective if a clear view of the posterior segment is possible.[37]

Retinal, Disc, and Macular Hemorrhages

These conditions are typically identified through spot clinical diagnoses using indirect ophthalmoscopy or 78D or 90D slit-lamp biomicroscopic examination. To determine the site, extent, and precise location of the hemorrhages, an OCT 5-line raster scan along the affected area is beneficial. OCT and OCT-A can provide additional information, such as the exact location of the bleed, associated signs of edema or subretinal fluid, any tractional components, and the integrity of the outer and inner retinal layers. FFA is useful for identifying ischemic areas, differentiating hemorrhages from neovascularization, and planning FFA-guided photocoagulation. ICG angiography is particularly helpful for the detailed evaluation of choroidal pathology due to its ability to distinctly visualize choroidal circulation. Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Auxiliary Lenses for Slit-Lamp Examination of the Retina," for more information.

Treatment / Management

In cases of traumatic injury, the patient's systemic condition and cardiorespiratory status should be stabilized first. After ensuring systemic stability, a thorough ocular examination should be conducted. Patients with hyphema or vitreous hemorrhage should sit or lie in a semireclined position and elevate the head of the bed to at least 30° while sleeping, allowing the blood to settle inferiorly and clear the visual axis. Patients should avoid coughing, sneezing, vomiting, and heavy lifting. Resting the eyes by refraining from activities such as reading, watching television, and using computers is recommended. Applying an eye patch can further promote rest and recovery.

Systemic predisposing factors, such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and cardiovascular instability, should be strictly controlled. If the patient is unable to tolerate a complete eye examination, topical anesthetics such as proparacaine may be used.[38] Intraocular pressure should be monitored regularly, and, if necessary, topical agents, including beta-blockers (timolol maleate), alpha agonists (brimonidine tartrate), carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (dorzolamide and brinzolamide), or prostaglandin analogs (latanoprost, travoprost, and bimatoprost) can be administered. Systemic agents such as intravenous mannitol, oral glycerol, or acetazolamide may be used in cases of acute, uncontrolled glaucoma. If glaucoma is ruled out, cycloplegic agents such as cyclopentolate or homatropine eye drops can be used for pain control, facilitating blood reabsorption and preventing pupillary movement, which may stretch injured blood vessels and increase the risk of rebleeding.[39] Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Hyphema," for more information. Topical steroid therapy with prednisolone acetate 1% or dexamethasone sodium phosphate 0.1% can help reduce inflammation, promote faster blood clearing, and stabilize inflamed vessels to minimize the risk of rebleeding.[40] (A1)

If hyphema responds to medical management, surgical intervention may not be necessary, as most cases can resolve completely with conservative treatment. However, if complications such as corneal staining, penetrating corneal injury, or elevated intraocular pressure unresponsive to medical therapy occur, surgical intervention, including anterior chamber lavage and management of associated complications, should be considered.[41]

Extra caution is required for patients with sickle cell anemia, as increased intraocular pressure can occur due to the sickling of red blood cells, which obstructs the trabecular meshwork. Surgical intervention should be considered if intraocular pressure exceeds 25 mmHg for more than 24 hours or fluctuates above 30 mmHg for 2 to 4 days.[42] In patients with vitreous hemorrhage where the fundus is not visible, B-scan ultrasonography should be performed to assess for retinal detachment. If the retina is attached, vitreous hemorrhage can be managed conservatively and reviewed every 1 to 2 weeks.

If the patient exhibits signs of improving vitreous hemorrhage, conservative medical management may be appropriate. In cases where the retina is only sparsely visible, especially in patients with proliferative retinopathies, laser photocoagulation should be initiated to minimize ischemic stimulation. Laser photocoagulation converts the ischemic retina to an anoxic state, thereby reducing the anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) load and decreasing the likelihood of rebleeding. If the patient does not show signs of improvement, they should be considered for intravitreal anti-VEGF therapy.

Commonly used doses for intravitreal injections include:

- Bevacizumab: 1.2 5 mg/0.05 mL

- Ranibizumab: 0.5 mg or 0.3 mg/0.05 mL

- Aflibercept: 2 mg/0.05 mL

- Pegaptanib: 0.3 mg/0.9 mL (approved by the US Food and Drug Administration [FDA] only for neovascular ARMD)

Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Diabetic Retinopathy," for more information.

If the hemorrhage does not resolve with the above management, pars plana vitrectomy should be considered. Many surgeons now inject intravitreal anti-VEGF medication into non-resolving vitreous hemorrhages 7 days before pars plana vitrectomy.[43] Indications for vitrectomy in diabetic patients include:(B2)

- Non-clearing vitreous hemorrhage (vitreous/subhyaloid/pre-macular)

- Tractional retinal detachment with the macula off

- Combined tractional with rhegmatogenous retinal detachment

- Anterior segment neovascularization with invisibility of the posterior segment

- Ghost cell glaucoma

- Thick epiretinal membrane

- Vitreomacular traction

Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Diabetic Retinopathy," for more information.

During vitrectomy surgery, 3 pars plana ports are created—one for the infusion line, one for the light pipe, and a third for the microinstruments. In addition, a fourth port may be added if a chandelier light source is used for bimanual vitrectomy.[44] Core vitrectomy is performed with guarded posterior vitreous detachment induction, followed by shaving the peripheral vitreous. All bleeding sites are cauterized, and any tractional components are removed. Fluid-air exchange is then conducted. If necessary, epiretinal membrane peeling, with or without ILM peeling, is performed with appropriate precautions. Endophotocoagulation is applied to non-perfused areas while sparing the macula. At the end of the surgery, a tamponade can be injected in the form of air, fluid, gas (such as octafluoropropane [C3F8] or sulfur hexafluoride [SF6]), or silicone oil.

Cryotherapy can be used to ablate the peripheral ischemic retina, and it disrupts the blood-retinal barrier, induces inflammation, and assists in removing red blood cells. Due to the intense inflammation caused by cryotherapy, it is not considered the first-line treatment for ablating ischemic areas. This procedure is indicated only when the fundus is nonvisible and to prevent neovascularization at port sites.[45] The diathermy procedure is now obsolete due to its adverse effects and the difficulty of maneuvering. In cases of rubeosis iridis, panretinal photocoagulation, with or without anti-VEGF medication, may be beneficial in the early phases. However, in advanced stages, new vessel formation leads to fibrosis and contracture, resulting in permanent distortion of the angles and refractory glaucoma, which may eventually require a glaucoma drainage implant. The prognosis in such cases is poor. Painful blind eyes may necessitate diode laser cyclophotocoagulation or cyclocryotherapy. Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Diabetic Retinopathy," for more information.

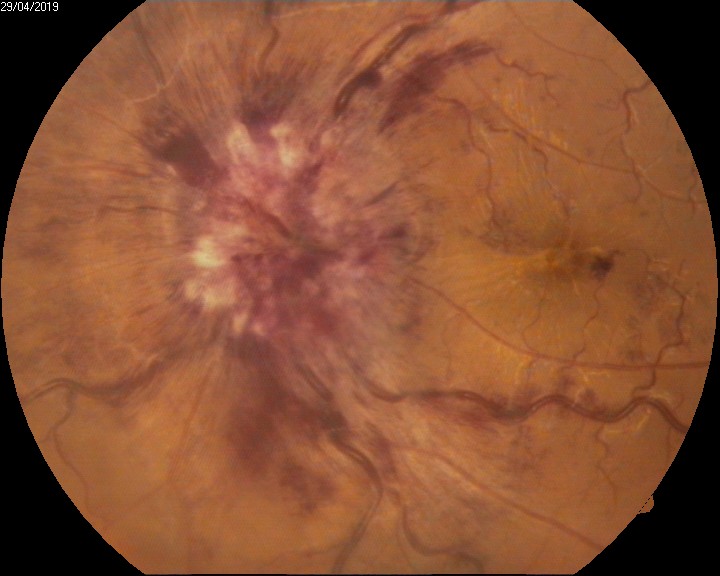

Isolated retinal hemorrhage not involving the macula can often be observed while stabilizing systemic predisposing factors. Disc hemorrhages themselves do not cause vision loss, but glaucoma must be ruled out. If glaucoma is present, the patient should begin appropriate antiglaucoma treatment. Additionally, any systemic metabolic dysfunction should be addressed if disc hemorrhages result from nonglaucomatous causes. Roth spots are typically asymptomatic and resolve spontaneously once the underlying condition is managed (see Image. Intraocular Hemorrhage With Roth Spots).

Subhyaloid hemorrhage can often be observed without affecting the macular area. However, when it involves the macula, it may result in significant vision loss. Treatment can be performed using a Q-switched 1064 nm Nd:YAG laser (energy range of 2.1-11.5 mJ), focused on the anterior border of the subhyaloid hemorrhage, particularly at the lower margin, inferior and away from the fovea.[46] Care must be taken to avoid damaging retinal vessels and causing iatrogenic injury. This treatment allows blood to flow into the vitreous cavity, improving visual acuity while potentially increasing the number of floaters.[47](B3)

Suprachoroidal hemorrhage is an ophthalmic emergency that requires prompt diagnosis and urgent management to prevent the acute expulsion of ocular contents. If suprachoroidal hemorrhage is detected intraoperatively, all wound sites should be immediately closed, and tight sutures should be applied at all entry points. If expulsion continues despite these measures, posterior sclerotomies or 25-gauge trocar-assisted transconjunctival drainage of the suprachoroidal hemorrhage should be performed to alleviate intraocular pressure and soften the eye.[20] Once the expulsion is under control, air or viscoelastic substances should be used to re-establish the anterior chamber. Postoperatively, intraocular pressure should be managed with topical or systemic antiglaucoma medications. Steroid drops may be administered to reduce inflammation, while cycloplegic agents can help alleviate pain and spasms. For pain management, oral or systemic analgesics should be provided, avoiding antiplatelet agents such as NSAIDs and aspirin to prevent further bleeding).[48](B3)

The conservative management of postoperative suprachoroidal hemorrhage remains the same as previously described. If intraocular pressure remains elevated and causes severe ocular pain, surgical intervention may be necessary. The point of suprachoroidal hemorrhage is assessed, and a conjunctival peritomy is performed at that quadrant. A radial scleral incision of approximately 3 to 4 mm is made until the suprachoroidal hemorrhage begins to efflux. If necessary, gentle pressure can be applied at the edge of the incision to facilitate blood expulsion from the suprachoroidal space.[49] Intraoperative collapse of the anterior chamber should be prevented using air, gas, liquid, or viscoelastic substances. If retinal detachment, vitreous hemorrhage, or any other visually threatening posterior segment pathology is identified that requires intervention after draining the suprachoroidal hemorrhage, pars plana vitrectomy should be performed. To prevent choroidal effusion, it is essential to ensure that the infusion cannula remains within the vitreous cavity and not in the suprachoroidal space.[20] (B3)

Macular hemorrhage is a sight-threatening condition that necessitates prompt intervention, as prolonged accumulation of blood in the macula can lead to photoreceptor degeneration and permanent visual loss.[50] If the macular bleed is due to retinal circulation involvement, anti-VEGF medications such as bevacizumab (not FDA approved) and ranibizumab (FDA approved) may be utilized. For pathologies involving choroidal circulation, intravitreal aflibercept has demonstrated a favorable response. A steroid implant may be considered for cases of refractory macular edema and hemorrhage that do not respond adequately to anti-VEGF medications. Additionally, photodynamic therapy could be used for patients unresponsive to anti-VEGF treatments.[48] Pneumatic displacement, either alone or combined with an intravitreal tissue plasminogen activator injection, can be attempted to clear the macula of blood, with the patient remaining in a face-down position for several days.[51] While macular translocation surgery can be performed in patients with macular hemorrhage, the procedure often yields disappointing results.[52] (B2)

Differential Diagnosis

Intraocular hemorrhage can result from various underlying conditions, necessitating a comprehensive differential diagnosis for effective management. Identifying the cause requires considering a broad spectrum of possibilities, including trauma, vascular disorders, retinal tears, systemic diseases, and malignancies. Each potential cause presents with unique clinical and diagnostic features, making careful evaluation essential to guide appropriate treatment. A thorough exploration of the differential diagnosis for each type of intraocular hemorrhage enables clinicians to pinpoint the origin of the bleeding and tailor interventions accordingly.

Differential Diagnoses of Hyphema

- Traumatic hyphema

- Hyphema secondary to intraocular procedures [53]

- Herpetic keratouveitis (blood-stained hypopyon)—secondary to herpes simplex virus and varicella zoster virus

- UGH syndrome [54]

- Uveitis

- Fuchs heterochromic iridocyclitis with Amsler sign. This condition may present with hemorrhage in the aspirated fluid obtained from vitreous tapping or anterior chamber paracentesis due to iris atrophy. This condition is believed to result from the rupture of fragile iris vasculature caused by this atrophy.

- Juvenile xanthogranuloma [55]

- Hyphema due to neovascularization of the iris and angle—secondary to severe retinal ischemia secondary to proliferative diabetic retinopathy, central retinal vein occlusion, or ocular ischemic syndrome.[56][57]

Differential Diagnoses of Vitreous Hemorrhage

- Vitritis should be ruled out along with associated findings such as keratic precipitates, anterior chamber reaction, posterior synechiae, festooned pupil, and complicated cataracts.

- A thorough fundus examination is essential to exclude chorioretinitis, retinitis, choroiditis, vasculitis, and exudative retinal detachment.

- Primary intraocular lymphoma (commonly known as Masquerade syndrome).

- Endophytic retinoblastoma (occurs in children).

- Asteroid hyalosis (does not cause visual impairment).

- Retinal detachment, which has to be differentiated from posterior hyaloid detachment associated with vitreous hemorrhage on B-scan ultrasonography.[58]

Differential Diagnoses of Retinal Hemorrhage

- In children, retinal hemorrhages can arise from various causes, including vacuum or forceps delivery, birth trauma, shaken baby syndrome, Coats disease, persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous, retinopathy of prematurity, and hematological disorders such as severe anemia and sickle cell retinopathy. Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Retinal Hemorrhage," for more information.

- In adults, retinal hemorrhages may result from trauma, diabetic retinopathy, hypertensive retinopathy, retinal venous occlusion, ocular ischemic syndrome, sickle cell retinopathy, juxtafoveal telangiectasia, retinal microaneurysms, elevated intracranial pressure, bleeding or coagulation disorders, and Valsalva retinopathy. Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Retinal Hemorrhage," for more information.

- A comprehensive systemic evaluation is essential to identify the underlying cause if Roth spots are observed. Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Roth Spots," for more information.

Differential Diagnoses of Disc Hemorrhage

Linear hemorrhages along the disc margin must be differentiated from other causes of hemorrhage aside from glaucoma. These conditions include:

- Posterior vitreous detachment from the disc area [59]

- Ischemic optic neuropathies

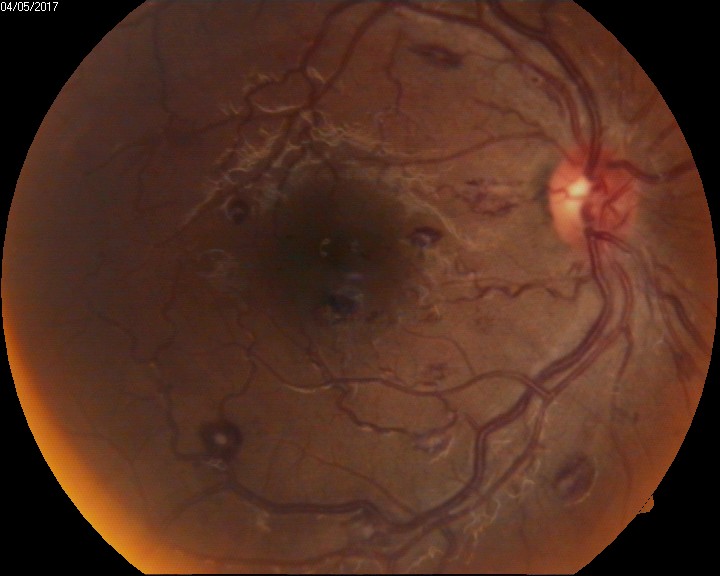

- Grade 4 hypertensive retinopathy (see Image. Intraocular Hemorrhage With Disc Hemorrhage in Grade 4 Papilledema)

- Diabetic papillopathy

- Systemic hypertension

- Leukemia

- Systemic lupus erythematosus

- Vascular anomalies at the disc [60]

Differential Diagnoses of Suprachoroidal Hemorrhage

- Retrobulbar hemorrhage

- Choroidal effusion (serous type)

- Hemorrhagic choroidal detachment

- Acute angle-closure glaucoma

- Choroidal hemangioma

- Posterior scleritis [61][62][63]

Differential Diagnoses of Macular Hemorrhage

- Choroidal neovascularization, secondary to ARMD

- Type I (under the RPE)

- Type II (under the neurosensory retina)

- Type III (retinal angiomatous proliferation)

- High myopia

- Idiopathic polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy [50]

- Choroidal rupture secondary to trauma [48]

- Angiod streaks

- Presumed ocular histoplasmosis

- Chorioretinitis or retinochoroiditis

- Secondary to laser photocoagulation

- Secondary to IOFB

- Ruptured retinal artery microaneurysm

- Valsalva retinopathy

- Anemic retinopathy (see Image. Intraocular Hemorrhage in Anemic Retinopathy)

- Leukemic retinopathy

- Secondary to an intraocular tumor (primary or metastatic)

- Secondary to diabetic retinopathy and retinal venous occlusion

- Secondary to bleeding and coagulation disorders [64]

Treatment Planning

Treatment planning for intraocular hemorrhage requires a comprehensive approach tailored to the severity of the bleeding, the underlying cause, and the patient’s overall health status. The primary objectives are to preserve vision, address the source of the hemorrhage, and prevent recurrence.

Assessment

- Clinical examination: If the view of the retina is obscured, a detailed eye examination is performed using slit-lamp biomicroscopy, indirect ophthalmoscopy, and B-scan ultrasonography.

- Imaging: OCT or FFA may be used to assess retinal involvement or other structural abnormalities.[65]

Treatment Strategies

- Observation: Small, noncomplicated hemorrhages may resolve spontaneously; therefore, regular monitoring is essential to ensure there is no progression.

- Medical management: Treatment may involve anti-VEGF injections for cases with neovascularization, corticosteroids for inflammation, and addressing systemic factors such as hypertension or anticoagulation therapy.

- Laser therapy: Panretinal photocoagulation may be indicated for hemorrhages related to diabetic retinopathy to prevent further neovascularization.

- Surgical interventions include the below-mentioned procedures.

- Vitrectomy: This procedure is indicated for dense or non-clearing hemorrhages or those associated with retinal detachment.

- Scleral buckling or retinopexy: This intervention is indicated if the hemorrhage is associated with retinal tears or detachment.[66]

Patient-Specific Considerations

- Age and comorbidities: Older patients or those with systemic conditions may necessitate a modified approach to minimize risks.

- Visual expectations: Patient counseling regarding potential visual outcomes is crucial.[67]

Follow-Up and Monitoring

- Post-treatment monitoring: Regular follow-ups are performed to monitor the resolution of the bleeding and detect any complications, such as retinal detachment or rebleeding.

- Rehabilitation: For patients with significant vision loss, visual rehabilitation strategies may include low vision aids and therapy.

By incorporating these components into the treatment plan, healthcare professionals can effectively manage intraocular hemorrhage, optimize patient outcomes, and preserve vision.[68]

Toxicity and Adverse Effect Management

In the management of intraocular hemorrhage, particularly with interventions such as pharmacological treatments, surgeries, or procedures, addressing potential toxicity and adverse effects is essential. Effective management requires a multidisciplinary approach, close monitoring, and proactive patient engagement to ensure optimal outcomes and mitigate risks associated with treatment.[69]

Pharmacological Management

- Corticosteroids: These medications are used to reduce inflammation, but they can also increase intraocular pressure, cause cataract formation, or delay wound healing. Monitoring intraocular pressure and providing adjunct treatments such as anti-glaucoma medications may be necessary.

- Antibiotics: Prophylactic antibiotics are often administered postoperatively. However, they can cause allergic reactions or antibiotic resistance. Therefore, it is necessary to use antibiotics with an appropriate spectrum and monitor for signs of adverse reactions.

- Anticoagulants/antiplatelets: These drugs, which are used for various systemic conditions, may exacerbate bleeding. A careful risk-benefit analysis is required, especially in patients with a history of bleeding.[70]

Surgical Management

- Vitrectomy: This is a common procedure utilized for dense vitreous hemorrhage, and it may carry risks, including retinal detachment, endophthalmitis, or progression of cataracts. Close postoperative monitoring and prompt management of any complications are crucial for optimal outcomes.

- Laser therapy: This is used to treat underlying causes of hemorrhage. Laser photocoagulation can lead to peripheral visual field loss, macular edema, or scarring. Thus, accurate targeting and minimizing exposure are essential to mitigate these risks.[71]

Monitoring and Preventive Strategies

- Routine monitoring: Regular follow-ups are recommended for detecting early signs of toxicity, particularly in patients undergoing long-term pharmacotherapy.

- Patient education: Patients should be educated about recognizing symptoms of toxicity, including visual disturbances, eye pain, or systemic adverse effects, and encouraged to report these symptoms promptly.

- Tailoring treatment: The treatment plan should be adjusted based on individual risk factors for toxicity, particularly for patients with preexisting conditions that may increase their susceptibility to adverse effects.

Staging

Intraocular hemorrhage lacks a universally recognized staging system because of its variable presentations and underlying causes. However, informal staging based on severity and location can assist in determining the appropriate intervention and prognosis, guiding clinical management according to its impact on visual function. Intraocular hemorrhage can be categorized into severity-based staging and anatomical location–based staging.

Severity-Based Staging

- Mild: Small, localized hemorrhage with minimal impact on vision (eg, small subconjunctival hemorrhage or mild vitreous hemorrhage).

- Moderate: More extensive hemorrhage that causes significant visual disturbance but does not pose an immediate threat to ocular structures (eg, moderate hyphema or larger vitreous hemorrhage).

- Severe: Extensive hemorrhage that poses a risk to vision and may necessitate urgent intervention (eg, dense vitreous hemorrhage, suprachoroidal hemorrhage, or large hyphema with increased intraocular pressure).

Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Subconjunctival Hemorrhage," for more information.

Anatomical Location-Based Staging

Anterior segment hemorrhages: These include the below-mentioned stages.

- Stage 1: Subconjunctival hemorrhage.

- Stage 2: Mild hyphema (blood in the anterior chamber filling less than 1/3 of the chamber).

- Stage 3: Moderate hyphema (blood filling between 1/3 and 1/2 of the chamber).

- Stage 4: Severe hyphema (complete filling of the anterior chamber).

Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Hyphema," for more information.

Posterior segment hemorrhages: These include the below-mentioned stages.

- Stage 1: Focal vitreous hemorrhage (small amount of blood in the vitreous).

- Stage 2: Diffuse vitreous hemorrhage (blood distributed diffusely but not obscuring the fundus).

- Stage 3: Dense vitreous hemorrhage (complete obscuration of the fundus, with potential for retinal detachment).

- Stage 4: Subretinal or submacular hemorrhage (blood beneath the retina or macula).

Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Retinal Hemorrhage," for more information.

Prognosis

The prognosis for different types of intraocular hemorrhage is influenced by several factors, including the location and volume of the bleed, the severity of the condition, the rate at which the blood clears, and whether the blood obstructs visual acuity. Additional complications associated with the hemorrhage—such as corneal staining, tractional retinal detachment, pre-retinal fibrosis, ischemic optic atrophy, and neovascular glaucoma—along with the severity of macular involvement also have significant roles in determining the overall prognosis.[72]

Hyphema generally has a favorable prognosis when not accompanied by other vision-threatening complications. However, higher grades of hyphema increase the risk of glaucoma and decrease the likelihood of achieving normal vision.[56] A study by Sanders et al found that blood from the vitreous cavity clears at a rate of 1% per day.[19] The prognosis for vitreous hemorrhage resulting from posterior vitreous detachment is typically good.[4] In contrast, the prognosis for vitreous hemorrhage or hyphema due to trauma is contingent on the complications associated with the traumatic injury. Specifically, choroidal rupture in the macular region is associated with a poor prognosis.

Terson syndrome, anemic retinopathy, and Valsalva retinopathy generally have a favorable prognosis.[73] In contrast, hemorrhage associated with wet ARMD and polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy has a relatively poor prognosis, as chronic heme collection at the macula can damage the photoreceptor layer and lead to scarring.[74] The prognosis for retinal vein occlusion varies based on the severity of the ischemic event, with ischemic central retinal vein occlusion presenting the worst prognosis among all types of retinal vein occlusion. Nonischemic branch retinal vein occlusion typically has the best prognosis. However, if retinal vein occlusion is accompanied by macular ischemia, the outlook is significantly worse.[75] The prognosis for retinal hemorrhage secondary to systemic metabolic dysfunction or retinal venous occlusion is contingent upon the extent of resolution of the underlying pathological condition.[76]

Traumatic retinal hemorrhages generally have a good prognosis unless they are associated with choroidal rupture in the macular area.[76] Early treatment of subhyaloid hemorrhage with Nd:YAG hyaloidotomy is associated with a better prognosis. Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Vitreous Hemorrhage," for more information. The prognosis for suprachoroidal hemorrhage, whether intraoperative or postoperative, is guarded and depends on preoperative visual acuity and the presence of retinal detachment alongside the hemorrhage.[63] Disc hemorrhage is associated with a risk of glaucoma, and the prognosis varies based on the progression and severity of the glaucoma.[77]

Complications

Intraocular hemorrhage can result in significant visual impairment if not addressed promptly. Recognizing the complications associated with this condition is essential, as they can vary from mild vision disturbances to severe and irreversible damage, including retinal detachment and glaucoma.

Complications of Subconjunctival Hemorrhage

- Recurrence of bleeding

- Secondary infection (rare)

- Conjunctival scarring (rare)

- Conjunctival cyst formation

Complications of Hyphema (Anterior Chamber Hemorrhage)

- Increased intraocular pressure [78]

- Risk of rebleeding [79]

- Corneal staining [56]

- Hypoxia in sickle cell anemia patients [80]

- In patients with sickle cell anemia, the hypoxic environment inside the anterior chamber increases the likelihood of sickling, leading to trabecular meshwork blockage by the sickled red blood cells and further worsening of the condition.

Complications of Vitreous Hemorrhage

- Epiretinal membrane formation

- Pigmentary retinopathy

- Preretinal fibrosis

- Strabismus (due to long-standing hemorrhage affecting the visual axis)

- Occlusion amblyopia (if the hemorrhage is obstructing the visual axis at an early age)

- Tractional retinal detachment

- Secondary rhegmatogenous retinal detachment

- Neovascular glaucoma

Complications of Suprachoroidal Hemorrhage

- Suprachoroidal hemorrhage is one of the most severe complications that can arise from intraocular surgery.

- Once a suprachoroidal hemorrhage occurs, visual recovery can be challenging, even with aggressive treatment measures.

Complications of Macular Hemorrhage

- Damage to photoreceptor cells

- Submacular fibrosis

- Retinal neovascularization (secondary to ischemia)

- Vitreoretinal fibrovascular proliferation

- Chronic heme collection can lead to macular scarring and drastic vision loss. Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Retinal Hemorrhage," for more information.

Complications of Subretinal Hemorrhage

- Retinal pigment epithelium atrophy

- Choroidal neovascularization

- Macular scar formation

- Retinal detachment

- Photoreceptor damage leading to vision loss

- Fibrosis and subretinal fibrosis [81]

Complications of Retinal Hemorrhage

- Macular edema

- Retinal vein occlusion

- Retinal ischemia and infarction

- Proliferative diabetic retinopathy (if associated with diabetes)

- Tractional retinal detachment

- Neovascularization

- Permanent vision loss

Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Retinal Hemorrhage," for more information.

Complications of Choroidal Hemorrhage

- Suprachoroidal hemorrhage

- Expulsive hemorrhage (during surgery)

- Retinal detachment

- Secondary glaucoma

- Optic nerve compression

- Vision loss [82]

Complications of Orbital Hemorrhage

- Proptosis

- Compressive optic neuropathy

- Orbital compartment syndrome

- Corneal exposure and ulceration

- Diplopia due to extraocular muscle dysfunction

- Blindness if untreated [83]

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Postoperative care for intraocular hemorrhage emphasizes monitoring, complication prevention, and visual recovery support. Following surgical interventions like vitrectomy or laser photocoagulation, patients require close observation for signs of recurrent bleeding, infection, or retinal detachment. Regular follow-up appointments with an ophthalmologist are essential to evaluate healing and ensure the stability of the eye.[84]

Effective postoperative care includes pain management, inflammation control, and prevention of further bleeding. Topical steroids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and other prescribed medications can help reduce inflammation and promote healing. If the patient was receiving anticoagulant therapy before the hemorrhage, careful management and potential adjustment of these medications are necessary. This should be done in collaboration with a hematologist to prevent rebleeding while minimizing the risk of thromboembolic events.[85]

Rehabilitation aims to optimize any remaining vision and enhance quality of life. For patients experiencing significant visual impairment, low vision aids, vision therapy, and occupational therapy may be recommended. Education on eye protection, avoiding activities that could increase intraocular pressure, and maintaining overall systemic health is crucial for long-term management. Additionally, emotional and psychological support, including counseling, can benefit patients adjusting to changes in vision. Postoperative and rehabilitation care aims to preserve as much vision as possible, prevent complications, and help patients achieve the best quality of life.[86]

Consultations

A multidisciplinary approach with specialist consultations is essential for managing intraocular hemorrhage. By engaging a comprehensive team of specialists, the underlying causes of the hemorrhage can be effectively addressed, and tailored interventions can be implemented to enhance patient outcomes, prevent recurrence, and ensure long-term visual health.[87] Early referral is critical in preventing long-term complications and preserving vision.

Ophthalmologists

The initial and most urgent consultation should be with an ophthalmologist, ideally one specializing in retinal diseases. The ophthalmologist will perform a comprehensive eye examination utilizing tools such as slit-lamp biomicroscopy, OCT, and B-scan ultrasonography. This assessment helps determine the extent of the bleeding, its impact on ocular structures, and whether immediate intervention is necessary.[87]

Retinal Specialists

In cases of severe intraocular hemorrhage or when there is a risk of retinal detachment, vitreous hemorrhage, or other complications, involving a retinal specialist is essential. They may perform or recommend procedures such as vitrectomy or laser photocoagulation to effectively manage the bleeding and prevent further damage to the retina. Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Retinal Hemorrhage," for more information.

Hematologists

Consultation with a hematologist is important for patients with a history of bleeding disorders, those on anticoagulant therapy, or individuals with concerns about coagulopathy. The hematologist can evaluate and manage any underlying blood disorders, adjust anticoagulation therapy, and provide recommendations to balance the risks of further bleeding with the necessity of anticoagulation.

Endocrinologists/Internal Medicine Physicians

Consultation with an endocrinologist or internist is essential if systemic conditions such as uncontrolled diabetes or hypertension contribute to intraocular hemorrhage. These specialists can optimize the management of diabetes, hypertension, and other metabolic disorders to help prevent future hemorrhages.[87]

Primary Care Physicians

A primary care physician has a vital role in the overall coordination of care by ensuring continuity of care, managing comorbid conditions, and facilitating communication among specialists to implement a comprehensive treatment plan. Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Retinal Hemorrhage," for more information.

Pharmacists

Pharmacists play a crucial role in medication management, particularly with anticoagulant or antiplatelet therapies. They can assist in adjusting dosages, recommending alternative treatments, and educating patients about medication adherence and potential adverse effects.

Cardiologists

Cardiologists are essential when intraocular hemorrhage is potentially linked to cardiovascular issues, such as hypertension or anticoagulant use related to heart disease. They can manage cardiovascular risk factors and collaborate with other specialists to ensure a comprehensive treatment approach.

Social Work or Patient Support Services

For patients experiencing significant visual impairment, engaging social work or patient support services can address psychosocial needs, offer resources for vision rehabilitation, and provide support for coping strategies related to daily living activities.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Any patient presenting with an intraocular hemorrhage for the first time should undergo a thorough ocular evaluation to determine the underlying cause of the bleeding. The patient should be appropriately counseled regarding the prognosis of intraocular hemorrhage depending on the location of the bleeding. Early diagnosis, timely management, and appropriate follow-up, tailored to the location and severity of the bleed, are essential. Systemic control of diabetes, hypertension, bleeding disorders, and coagulopathies is crucial to prevent irreversible worsening of the intraocular hemorrhage. Subconjunctival hemorrhage and periorbital ecchymosis generally have a good prognosis and often resolve on their own. Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Ocular Trauma Prevention Strategies and Patient Counseling," for more information.

Cold compression can help speed up recovery. In cases of hyphema or vitreous hemorrhage, sitting upright or maintaining a semi-reclined position can keep the blood inferiorly positioned, reducing obstruction of the visual axis and minimizing discomfort in visual acuity. Lifestyle modifications, along with appropriate systemic and topical medications, should be recommended to prevent further bleeding or progression of coagulation disorders. Activities such as heavy lifting, excessive coughing, sneezing, Valsalva maneuvers, stress, and insufficient sleep should be avoided during active hemorrhage. If intraocular hemorrhage affecting visual acuity does not resolve with medical management, surgical intervention may be required.[88]

Patients on anticoagulant therapy should be informed of the potential risks and the need for regular monitoring, including frequent INR checks, to prevent excessive bleeding. Educating patients to recognize early signs of hemorrhage, such as sudden vision changes or the appearance of floaters, can facilitate timely medical intervention and help prevent more severe outcomes. Additionally, maintaining a healthy diet, avoiding smoking, and managing stress can support overall vascular health and reduce bleeding risk. Empowering patients with knowledge and preventive strategies can significantly lower the likelihood of intraocular hemorrhage and its associated complications.[89]

Pearls and Other Issues

Healthcare professionals can improve outcomes and reduce the risk of complications in patients with intraocular hemorrhage by adhering to best practices and a multidisciplinary approach. Key insights include the below-mentioned criteria.

Clinical Pearls

Early detection and intervention are essential for effective management of intraocular hemorrhage. A multidisciplinary approach involving ophthalmologists, primary care providers, pharmacists, and other healthcare providers ensures comprehensive patient care. Essential diagnostic tools include OCT and ultrasound, which help assess the severity of the hemorrhage and guide appropriate treatment. Prompt intervention can prevent complications such as retinal detachment and permanent vision loss. Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Pediatric Cataract," for more information.

Disposition

Patients with intraocular hemorrhage require close monitoring, especially if they have underlying conditions such as diabetes or hypertension. Outpatient follow-up with regular eye exams is essential to track progress and detect any new complications. If the bleeding persists or worsens, surgical intervention such as a vitrectomy may be necessary.[3]

Pitfalls

Delays in diagnosis and treatment can lead to worsening hemorrhage and potential vision loss. Mismanagement of anticoagulant therapy may exacerbate bleeding, highlighting the need for careful medication review and adjustment. Failure to manage underlying systemic conditions, such as hypertension, can result in recurrent hemorrhages.

Prevention

Effective management of systemic risk factors, such as hypertension and diabetes, is crucial in preventing intraocular hemorrhage. Regular eye examinations for at-risk patients enable early detection and intervention. Careful monitoring and dosage adjustments based on regular INR checks for individuals on anticoagulants can help minimize the risk of bleeding. Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Anticoagulation Safety," for more information.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Managing intraocular hemorrhage requires a collaborative approach involving physicians, advanced practitioners, nurses, pharmacists, and other healthcare professionals to optimize patient outcomes and ensure safety. The multidisciplinary healthcare team must exercise skills in early diagnosis, effective treatment planning, and timely interventions. Physicians and advanced practitioners lead the assessment of bleeding severity and determine appropriate medical or surgical interventions. Nurses are crucial in monitoring patient progress, administering medications, and providing postoperative care. Pharmacists contribute by ensuring proper anticoagulant use and managing medication-related complications while coordinating with the rest of the care team to support effective treatment planning and timely interventions.

Patients typically present to their primary care physician or nurse practitioner, who should recognize the condition's treatable nature. A prompt referral to an ophthalmologist is essential.[90] Intraocular hemorrhage patients should not rely solely on ophthalmological treatment; they also require a multidisciplinary evaluation involving specialists such as endocrinologists, nephrologists, cardiologists, and neurologists. This collaborative, interdisciplinary approach ensures optimal patient outcomes.[91] In addition, effective interprofessional communication and coordination are essential to prevent misunderstandings and create a cohesive treatment plan that addresses the patient's unique needs. Ethical considerations, including informed consent and patient autonomy, are central to care, ensuring that patients and their families fully understand the risks, benefits, and alternatives of the proposed interventions.

Affected patients can be monitored by their primary clinicians, who should ensure correct dosing for medication management. Nursing will be the first department to follow up with patients, assess treatment progress, evaluate compliance with both medication and lifestyle measures, and report any issues to the primary care physician. By fostering a patient-centered approach and prioritizing interprofessional collaboration, the healthcare team can significantly enhance the management of intraocular hemorrhage, leading to better clinical outcomes and improved patient safety. Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Cornea Transplantation," for more information.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Shaikh N, Kumar V, Ramachandran A, Venkatesh R, Tekchandani U, Tyagi M, Jayadev C, Dogra M, Chawla R. Vitrectomy for cases of diabetic retinopathy. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2024 Aug 14:():. doi: 10.4103/IJO.IJO_30_24. Epub 2024 Aug 14 [PubMed PMID: 39186637]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSankar PS, Chen TC, Grosskreutz CL, Pasquale LR. Traumatic hyphema. International ophthalmology clinics. 2002 Summer:42(3):57-68 [PubMed PMID: 12131583]

Shaikh N, Srishti R, Khanum A, Thirumalesh MB, Dave V, Arora A, Bansal R, Surve A, Azad S, Kumar V. Vitreous hemorrhage - Causes, diagnosis, and management. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2023 Jan:71(1):28-38. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_928_22. Epub [PubMed PMID: 36588205]

Spraul CW, Grossniklaus HE. Vitreous Hemorrhage. Survey of ophthalmology. 1997 Jul-Aug:42(1):3-39 [PubMed PMID: 9265701]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJiang H, Gao Y, Fu W, Xu H. Risk Factors and Treatments of Suprachoroidal Hemorrhage. BioMed research international. 2022:2022():6539917. doi: 10.1155/2022/6539917. Epub 2022 Jul 14 [PubMed PMID: 35872859]

Park HY, Jeong HJ, Kim YH, Park CK. Optic disc hemorrhage is related to various hemodynamic findings by disc angiography. PloS one. 2015:10(4):e0120000. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120000. Epub 2015 Apr 16 [PubMed PMID: 25879852]

Nakagawa S, Ishii K. Massive intraocular hemorrhage, presumably from the central retinal artery after cataract surgery, and difficult hemostasis during vitrectomy: a case report. BMC ophthalmology. 2022 Aug 8:22(1):336. doi: 10.1186/s12886-022-02555-z. Epub 2022 Aug 8 [PubMed PMID: 35941541]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceOska N, Azad F, Saad M, Juzych M. Seeing through the strikes: a comprehensive study of ocular injuries in martial arts from 2012 to 2021. Canadian journal of ophthalmology. Journal canadien d'ophtalmologie. 2024 Aug 22:():. pii: S0008-4182(24)00252-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2024.08.006. Epub 2024 Aug 22 [PubMed PMID: 39181158]

Ribeiro M, Monteiro DM, Moleiro AF, Rocha-Sousa A. Perioperative suprachoroidal hemorrhage and its surgical management: a systematic review. International journal of retina and vitreous. 2024 Aug 21:10(1):55. doi: 10.1186/s40942-024-00577-x. Epub 2024 Aug 21 [PubMed PMID: 39169423]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKaur B, Taylor D. Retinal haemorrhages. Archives of disease in childhood. 1990 Dec:65(12):1369-72 [PubMed PMID: 2103739]

Quigley HA, Addicks EM, Green WR, Maumenee AE. Optic nerve damage in human glaucoma. II. The site of injury and susceptibility to damage. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 1981 Apr:99(4):635-49 [PubMed PMID: 6164357]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKennedy RH, Brubaker RF. Traumatic hyphema in a defined population. American journal of ophthalmology. 1988 Aug 15:106(2):123-30 [PubMed PMID: 3400754]

Butner RW, McPherson AR. Spontaneous vitreous hemorrhage. Annals of ophthalmology. 1982 Mar:14(3):268-70 [PubMed PMID: 7092037]

Winslow RL, Taylor BC. Spontaneous vitreous hemorrhage: etiology and management. Southern medical journal. 1980 Nov:73(11):1450-2 [PubMed PMID: 7444506]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceObuchowska I, Mariak Z. Risk factors of massive suprachoroidal hemorrhage during extracapsular cataract extraction surgery. European journal of ophthalmology. 2005 Nov-Dec:15(6):712-7 [PubMed PMID: 16329055]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAl-Hity A, Steel DH, Yorston D, Gilmour D, Koshy Z, Young D, Hillenkamp J, McGowan G. Incidence of submacular haemorrhage (SMH) in Scotland: a Scottish Ophthalmic Surveillance Unit (SOSU) study. Eye (London, England). 2019 Mar:33(3):486-491. doi: 10.1038/s41433-018-0239-4. Epub 2018 Oct 29 [PubMed PMID: 30374150]

Barlow KM, Minns RA. Annual incidence of shaken impact syndrome in young children. Lancet (London, England). 2000 Nov 4:356(9241):1571-2 [PubMed PMID: 11075773]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKelly P, Farrant B. Shaken baby syndrome in New Zealand, 2000-2002. Journal of paediatrics and child health. 2008 Mar:44(3):99-107 [PubMed PMID: 18086144]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSanders D, Peyman GA, Fishman G, Vlchek J, Korey M. The toxicity of intravitreal whole blood and hemoglobin. Albrecht von Graefes Archiv fur klinische und experimentelle Ophthalmologie. Albrecht von Graefe's archive for clinical and experimental ophthalmology. 1975 Dec 4:197(3):255-67 [PubMed PMID: 813541]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChu TG, Green RL. Suprachoroidal hemorrhage. Survey of ophthalmology. 1999 May-Jun:43(6):471-86 [PubMed PMID: 10416790]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceObuchowska I, Mariak Z, Stankiewicz A. [The evaluation of incidence of massive suprachoroidal hemorrhage n the material of the Department of Ophthalmology, Medical Academy in Bialystok from 1990 to 2000]. Klinika oczna. 2002:104(2):93-5 [PubMed PMID: 12174463]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceObuchowska I, Mariak Z. [A new approach towards pathogenesis and treatment of massive suprachoroidal hemorrhage]. Klinika oczna. 2002:104(2):138-42 [PubMed PMID: 12174457]

Scott IU, Flynn HW Jr, Schiffman J, Smiddy WE, Murray TG, Ehlies F. Visual acuity outcomes among patients with appositional suprachoroidal hemorrhage. Ophthalmology. 1997 Dec:104(12):2039-46 [PubMed PMID: 9400763]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePark HL, Kim JW, Park CK. Choroidal Microvasculature Dropout Is Associated with Progressive Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer Thinning in Glaucoma with Disc Hemorrhage. Ophthalmology. 2018 Jul:125(7):1003-1013. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2018.01.016. Epub 2018 Mar 2 [PubMed PMID: 29486903]

Uhler TA, Piltz-Seymour J. Optic disc hemorrhages in glaucoma and ocular hypertension: implications and recommendations. Current opinion in ophthalmology. 2008 Mar:19(2):89-94. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e3282f3e6bc. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18301280]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSeol BR, Jeoung JW, Park KH. Ocular and systemic risk factors associated with recurrent disc hemorrhage in primary open-angle glaucoma. PloS one. 2019:14(9):e0222166. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0222166. Epub 2019 Sep 16 [PubMed PMID: 31525246]

Blumenthal I. Shaken baby syndrome. Postgraduate medical journal. 2002 Dec:78(926):732-5 [PubMed PMID: 12509690]

Türkmen N, Eren B, Fedakar R, Akgöz S. The significance of hemosiderin deposition in the lungs and organs of the mononucleated macrophage resorption system in infants and children. Journal of Korean medical science. 2008 Dec:23(6):1020-6. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2008.23.6.1020. Epub 2008 Dec 24 [PubMed PMID: 19119447]

Chew Bonilla A, Bueno Zarazúa P, Rosales Padron J, Fulda Graue E, Graue Wiechers F. Delayed manifestation of proliferative retinopathy associated with chronic myeloid leukemia. American journal of ophthalmology case reports. 2024 Dec:36():102132. doi: 10.1016/j.ajoc.2024.102132. Epub 2024 Jul 25 [PubMed PMID: 39161376]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGebara A, Vofo BN, Jaouni T. Branch retinal artery occlusion from laser pointer misuse. American journal of ophthalmology case reports. 2024 Dec:36():102118. doi: 10.1016/j.ajoc.2024.102118. Epub 2024 Jul 18 [PubMed PMID: 39156905]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHirano Y, Suzuki N, Tomiyasu T, Kurobe R, Yasuda Y, Esaki Y, Yasukawa T, Yoshida M, Ogura Y. Multimodal Imaging of Microvascular Abnormalities in Retinal Vein Occlusion. Journal of clinical medicine. 2021 Jan 21:10(3):. doi: 10.3390/jcm10030405. Epub 2021 Jan 21 [PubMed PMID: 33494354]

Sotani Y, Imai H, Kishi M, Yamada H, Matsumiya W, Miki A, Kusuhara S, Nakamura M. Removal of Subinternal Limiting Membrane Hemorrhage Secondary to Valsalva Retinopathy Using a Fovea-Sparing Internal Limiting Membrane Fissure Creation Technique. Case reports in ophthalmological medicine. 2024:2024():2774155. doi: 10.1155/2024/2774155. Epub 2024 Aug 13 [PubMed PMID: 39165514]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePozzato I, Craig A, Gopinath B, Kifley A, Tran Y, Jagnoor J, Cameron ID. Outcomes after traffic injury: mental health comorbidity and relationship with pain interference. BMC psychiatry. 2020 Apr 28:20(1):189. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02601-4. Epub 2020 Apr 28 [PubMed PMID: 32345257]

Petrie JR, Guzik TJ, Touyz RM. Diabetes, Hypertension, and Cardiovascular Disease: Clinical Insights and Vascular Mechanisms. The Canadian journal of cardiology. 2018 May:34(5):575-584. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2017.12.005. Epub 2017 Dec 11 [PubMed PMID: 29459239]

Aironi VD, Gandage SG. Pictorial essay: B-scan ultrasonography in ocular abnormalities. The Indian journal of radiology & imaging. 2009 Apr-Jun:19(2):109-15. doi: 10.4103/0971-3026.50827. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19881064]