Introduction

Acute paronychia is one of the most common infections of the hand.[1][2] It is usually caused by a breakdown of the seal between the nail plate and the nail fold with infection resulting from subsequent inoculation of bacterial or fungal pathogens.[3] This is typically precipitated by nail-biting, trauma, manicures, ingrown nails, and hangnail manipulation. Abscess involving pus within the soft tissues adjacent to the nail may occur, indicating the need for surgical drainage.

From a microbiology perspective, paronychia of the hand is reported to be a polymicrobial infection with mixed aerobic and anaerobic bacterial flora in around 50% of cases.[4] The most common infective pathogen is Staphylococcus aureus (including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA)), but other aerobic bacteria may include Streptococcus species or gram-negative bacteria. While anaerobic florae such as Bacteroides, Enterococcus species, or Eikenella corrodens are associated with exposure to oral secretions through nail-biting and digital sucking practices (more common in children).[2][4] Clinical history and local antibiotic guidance, including consideration of MRSA rates, should direct the prescription of antibiotics.[5] Non-bacterial infections are less common but may include fungal infections such as Candida albicans and viral infections such as herpes simplex.

If a paronychia has been present for less than six weeks, it is classified as acute, whereas those present for six weeks or more are classified as chronic.[6] Chronic paronychia is a multifactorial inflammatory condition primarily caused by exposure to environmental allergens or irritants.[2] The disruption to the protective barrier caused by this inflammatory process may result in colonization with bacterial or fungal organisms. Candida albicans is the most commonly implicated micro-organism.[7] With differing etiologies and treatment approaches, chronic paronychia should be considered a separate entity from acute paronychia, which is the focus of this article.

Another important differential diagnosis is herpetic whitlow, a herpes simplex virus infection that may manifest clinically with the presence of blisters involving the distal phalanx. Surgical drainage is contraindicated unless a concurrent bacterial infection is present.[2]

Paronychia involving toes is a relatively common condition and may be associated with ingrowing toenails.[2] Although treatment approaches may be similar, the focus of this article is the management of acute paronychia drainage of the hand.

Clinical Assessment and Diagnosis

Acute paronychia is diagnosed clinically with pain, swelling, and erythema of the nail folds. Formation of pus along the paronychial fold may occur; if untreated, an abscess may progress to involve the eponychium and the area below the nail plate. This can generally be identified by the presence of a tender, boggy swelling. As described by Turkmen et al., the digital pressure test can also be used to evaluate the presence of pus within the soft tissue. If light pressure is applied to the volar aspect of the tip of the affected digit, a localized region of skin blanching around the nail may indicate the presence of an underlying abscess.[8] Furthermore, if pus is deep to the nail plate, it may be visible on inspection and ballotable on palpation.

A felon is an infection in the pulp of the distal phalanx of a digit and is a separate condition from paronychia. Although a paronychia can lead to the development of a felon, the presence of one does not indicate the presence of the other. Careful examination of the digit should be performed to identify the clinical presence of a felon and thus the need for surgical drainage. This is characterized by a tender, fluctuant swelling involving the pulp of the digit.[1] This article will only discuss acute paronychia drainage.

In the early stage of paronychia, inflammation of the paronychial fold alone may be present, without pus formation. The majority of such cases may be managed non-operatively in the primary care or emergency department setting. Treatment involving oral antibiotics with close monitoring comprising follow-up appointments and patient safety advice is recommended. Oral antibiotics with gram-positive coverage are advised, or if suspecting exposure to oral bacteria, a broad-spectrum agent is preferable.[6][7][9] Although some authors recommend using antiseptic or warm water soaks, there is no clear evidence to recommend their use routinely in any stage of the condition.[2][9]

In the later stage of paronychia, the presence of pus in the form of a local abscess may be present. Laboratory and radiological investigations are important in this stage. Plain film radiographs of the involved digit are used to investigate the possibility of associated foreign bodies, fractures, or osteomyelitis. Glucose testing is important to review glycemic control in patients with diabetes and may occasionally identify undiagnosed diabetes. Extended laboratory blood tests such as full blood count and inflammatory markers are generally only indicated in more severe cases where marked cellulitis or tracking lymphangitis is present. In all cases of paronychia with abscesses, surgical drainage is indicated. This may be performed in primary care or emergency department settings depending on local resources and expertise. Referral to tertiary hand surgery may otherwise be required.[1]

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

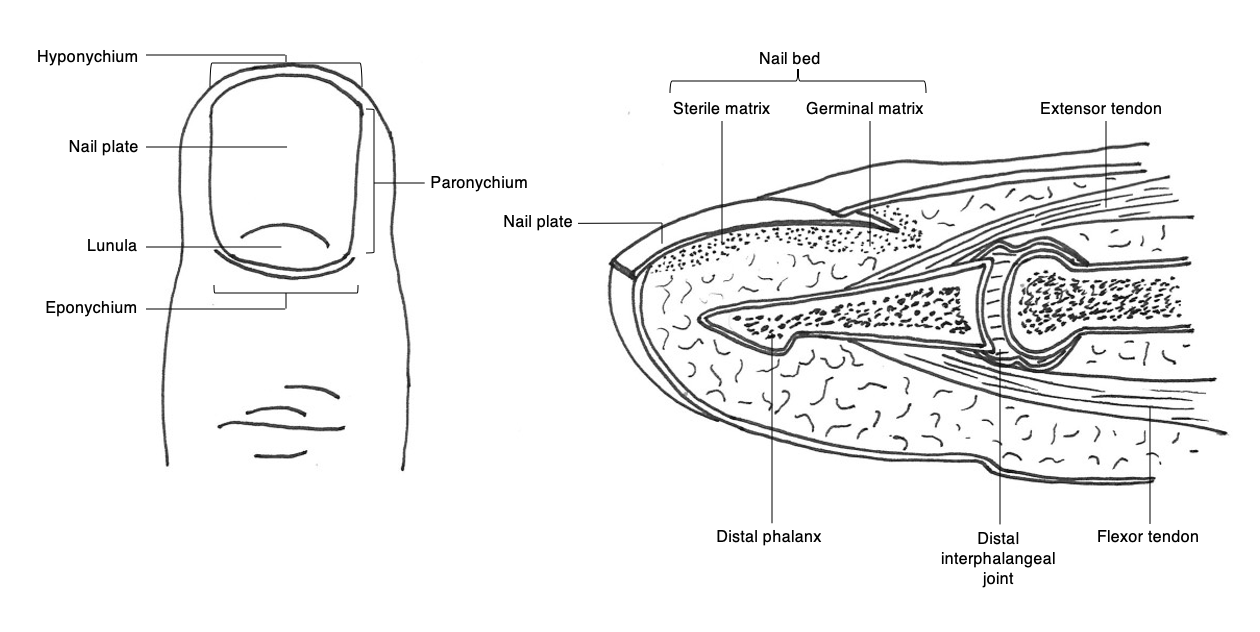

The tip of the digit distal to insertions of the tendons consists of the bony elements and soft tissue structures, including specialized tissues that function to develop and support the nail.[10] These specialized tissues consist of the nail plate, perionychium, and nail bed (Figure 1). The nail plate is the hard keratinous component of the fingertip and, in humans, functions to aid fine motor tasks through the provision of grip as well as a counterpressure surface to the finger pulp to enhance fine touch sensation.[6] The perionychium comprises the soft tissues bordering the nail plate with the components defined by their anatomical relationship to the nail plate, including the paronychium laterally, hyponychium distally, and eponychium proximally. The nail bed, also considered a constituent of the perionychium, is divided into the germinal and sterile matrices. The germinal matrix is responsible for the majority of the growth of the nail plate through gradient parakeratosis.[11] It is located deep to the eponychial fold proximally with termination at the crescent-shaped lunula – visible through the nail plate. The sterile matrix is the darker-colored region distal to the lunula and functions to strengthen and anchor the nail plate.

In the case of abscess formation, initial fluctuance may be present at the paronychium unilaterally, although this may progress to involve the eponychium, contralateral paronychium, or nail bed beneath the nail plate. In the case of all components being involved, the condition is more precisely termed a paronychial infection.[6] If unmanaged, sequelae may include disruption of nail growth, felon, osteomyelitis, cellulitis, and tracking lymphangitis.

Indications

The drainage of acute paronychia is indicated with a well-defined abscess, or there has been a failure of conservative treatment with oral antibiotics.[5] [Level 5]

Contraindications

There are no absolute contraindications to the drainage of acute paronychia. General considerations for a local anesthetic hand procedure such as anticoagulant use, control of diabetes, and other patient factors should be considered.

Equipment

- Personal protective equipment (PPE) including a mask, eye protection, sterile gloves

- Antiseptic preparation such as chlorhexidine solution or povidone-iodine solution

- Sterile drape

- Digital block using a 10 mL syringe, 25 to 27-gauge needle, local anesthetic, e.g., 1% lidocaine with epinephrine

- Finger tourniquet (optional)

- Scalpel blade (number 11 or 15)

- 23-gauge or 21-gauge needle

- Scissors (ideally tenotomy scissors if available)

- Small forceps

- Nail elevator device (e.g., Freer elevator or Mitchell trimmer if available)

- Irrigation solution, e.g., normal saline +/- antiseptic solution

- Dressings: Interface dressing (e.g., silicon-based dressing), gauze, and digital dressing

- Microbiology sampling equipment including a microbiology swab or 1 mL syringe for fluid sampling

Personnel

This procedure requires only a single individual, e.g., an emergency medicine physician, primary care physician, nurse practitioner, or surgeon. However, with a less compliant patient, such as a young child or patients with disorders such as autism or developmental delay, additional staff may be needed. This may be either to provide distraction techniques or use a general anesthetic to allow safe completion of the procedure.

Preparation

Informed consent should be obtained from the patient or guardian before performing the procedure. The procedure, post-operative regime, intended benefits, and possible complications should be explained in full. For example, if nail plate removal is planned as part of the procedure, the usual outcome of full nail regrowth within 3-4 months should be explained.[12] All potential risks are discussed within the complications section.

The affected hand should be cleaned with an antiseptic preparation, and a sterile drape applied. Paronychias are usually very tender, necessitating a digital local anesthetic block to allow complete drainage of the abscess during the procedure. 1% lidocaine with epinephrine is safe in healthy individuals. The epinephrine can produce an occlusive effect with reduced bleeding, which many surgeons prefer over digital tourniquet use.[13] A digital tourniquet is advised when using plain 1% lidocaine and occasionally when using lidocaine with epinephrine if bleeding becomes problematic. This functions to reduce procedural bleeding and allows accurate visualization of tissue planes.

Technique or Treatment

Although there is no widely agreed consensus on specific surgical drainage techniques, approaches are generally adapted based on the anatomical location and extent of the pus present.[5] Abscesses may broadly be divided into those involving the paronychium alone, extending into the eponychium, or extending into the nailbed.

If the abscess only involves the paronychial fold (see clinical image), decompression may be achieved by placing a surgical device within the sulcus between the lateral nail fold and the nail plate to allow elevation. This may be performed using a blunt device such as a nail elevator, or a sharp device such as a scalpel, scissors, or a bevel up 21 to 23 gauge needle directed away from the nail bed.[14][15]

If a small abscess involves the eponychium, the eponychial fold may be raised using a similar technique in the transverse plane. Small collections of pus may be decompressed with a limited incision through the most fluctuant point of the swelling.[6] If eponychial or paronychial fold abscesses are more extensive with the presence of large fluctuant swellings, examination for pus deep to the nail bed should be undertaken to determine if nail plate removal is indicated.

If there is pus underneath the nail plate forming a subungual abscess, complete removal of the nail plate is recommended. Complete nail plate removal is performed by using an elevator device both to loosen adherence to the eponychial and paronychial folds surrounding the nail plate and elevate it off the nail bed.[1] In the context of an abscess, the nail plate tends to pull off the nail bed easily with gentle traction, although forceps or a needle holder may be used to grasp the plate and remove using a rolling motion in the transverse direction. Complete nail plate removal offers advantages by ensuring maximal decompression of subungual pus, minimal associated patient morbidity, and is a straightforward, easily taught procedure. Although some authors recommend partial removal of the nail plate for subungual abscesses, this approach risks incomplete pus decompression, is more technically challenging, and with insufficient evidence to suggest superior patient outcomes.[1][2] While some physicians may be concerned that complete nail plate removal may result in abnormal nail growth, evidence in the trauma setting suggests the vast majority of nails regrow without significant deformity 3 to 4 months after surgical removal.[12]

In all cases of paronychial drainage, microbiological sampling either through swab or preferably fluid sampling with a syringe should be undertaken and sent for culture and sensitivities. Following adequate abscess exposure - debridement of non-viable tissue and a thorough washout with saline and a disinfectant solution are recommended. Digital dressings may be applied using an interface dressing and gauze and digital bandage.

Following the procedure, most patients may be discharged home, with hospital admission only indicated in cases associated with major complications such as cellulitis, tracking lymphangitis, or osteomyelitis. Generally, oral antibiotics should be prescribed for 7 to 10 days, although one study has disputed the requirement for antibiotic therapy if the abscess has been fully drained.[16] The patient should be reviewed for a wound clean and dressing change at 48 to 72 hours, with a review of bacterial culture results to ensure sensitivity to prescribed antibiotics.

Complications

Major complications of surgical drainage are uncommon but may occur. Risks should be explained to the patient during the consent process, including general risks and specific risks. General risks include pain, bleeding, infection, and scarring. Specific risks include recurrence or incomplete removal of infection, damage to surrounding structures, and abnormal nail growth.

Recurrence or persistence of the infection or pus may occur due to incomplete drainage or resistance to prescribed antimicrobial agents, with a higher risk in immunosuppressed patients.[9] Later sequelae of a persistent abscess include osteomyelitis, felon, cellulitis, and sepsis. Abnormal nail growth is uncommon and most commonly occurs due to the infection, although it can sometimes be iatrogenic.

Clinical Significance

Paronychia is a common infection in both children and adults in primary care, emergency department, and surgical units. While most can be treated conservatively with antibiotics, the presence of an abscess indicates the need for surgical drainage.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Paronychia drainage can be performed by an emergency medicine physician, primary care provider, surgeon, urgent care physician, physician’s assistant, or nurse practitioner. Although most described techniques are relatively simple with few complications, sufficient experience is necessary to correctly identify the extent of the abscess and ensure complete drainage.[5] If there is uncertainty regarding management or no response to initial treatment, referral to an appropriate tertiary surgery service is advisable. Most infections will resolve quickly after drainage, but adequate follow-up arrangements are essential, either in hospital dressing clinics or primary care. Understanding the condition, including identifying complications and reviewing microbiology results, is important during this period to reduce complications and optimize patient outcomes.[7] [Level 5] Interprofessional collaboration and communication are important to ensure good patient outcomes, while patient education is essential for awareness concerning clinical features. This will include the efforts of clinicians, mid-level practitioners, and nursing staff, all coordinating activity and sharing open communication to achieve optimal patient outcomes. [Level 5]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Ong YS, Levin LS. Hand infections. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2009 Oct:124(4):225e-233e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181b458c9. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19935282]

Lomax A, Thornton J, Singh D. Toenail paronychia. Foot and ankle surgery : official journal of the European Society of Foot and Ankle Surgeons. 2016 Dec:22(4):219-223. doi: 10.1016/j.fas.2015.09.003. Epub 2015 Sep 21 [PubMed PMID: 27810017]

Koshy JC, Bell B. Hand Infections. The Journal of hand surgery. 2019 Jan:44(1):46-54. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2018.05.027. Epub 2018 Jul 14 [PubMed PMID: 30017648]

Brook I. Paronychia: a mixed infection. Microbiology and management. Journal of hand surgery (Edinburgh, Scotland). 1993 Jun:18(3):358-9 [PubMed PMID: 8345268]

Ritting AW, O'Malley MP, Rodner CM. Acute paronychia. The Journal of hand surgery. 2012 May:37(5):1068-70; quiz page 1070. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2011.11.021. Epub 2012 Feb 3 [PubMed PMID: 22305431]

Shafritz AB, Coppage JM. Acute and chronic paronychia of the hand. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2014 Mar:22(3):165-74. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-22-03-165. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24603826]

Rigopoulos D, Larios G, Gregoriou S, Alevizos A. Acute and chronic paronychia. American family physician. 2008 Feb 1:77(3):339-46 [PubMed PMID: 18297959]

Turkmen A, Warner RM, Page RE. Digital pressure test for paronychia. British journal of plastic surgery. 2004 Jan:57(1):93-4 [PubMed PMID: 14672686]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJebson PJ. Infections of the fingertip. Paronychias and felons. Hand clinics. 1998 Nov:14(4):547-55, viii [PubMed PMID: 9884893]

Fassler PR. Fingertip Injuries: Evaluation and Treatment. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 1996 Jan:4(1):84-92 [PubMed PMID: 10795040]

Zook EG. Anatomy and physiology of the perionychium. Hand clinics. 1990 Feb:6(1):1-7 [PubMed PMID: 2179232]

Greig A, Gardiner MD, Sierakowski A, Zweifel CJ, Pinder RM, Furniss D, Cook JA, Beard D, Farrar N, Cooper CD, Jain A, NINJA Pilot Collaborative. Randomized feasibility trial of replacing or discarding the nail plate after nail-bed repair in children. The British journal of surgery. 2017 Nov:104(12):1634-1639. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10673. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29044488]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLalonde DH. Discussion: Wide-Awake Surgical Management of Hand Fractures: Technical Pearls and Advanced Rehabilitation. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2019 Mar:143(3):811-812. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000005380. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30817653]

Rockwell PG. Acute and chronic paronychia. American family physician. 2001 Mar 15:63(6):1113-6 [PubMed PMID: 11277548]

Ogunlusi JD, Oginni LM, Ogunlusi OO. DAREJD simple technique of draining acute paronychia. Techniques in hand & upper extremity surgery. 2005 Jun:9(2):120-1 [PubMed PMID: 16201254]

Pierrart J, Delgrande D, Mamane W, Tordjman D, Masmejean EH. Acute felon and paronychia: Antibiotics not necessary after surgical treatment. Prospective study of 46 patients. Hand surgery & rehabilitation. 2016 Feb:35(1):40-3. doi: 10.1016/j.hansur.2015.12.003. Epub 2016 Feb 16 [PubMed PMID: 27117023]